Rock–paper–scissors

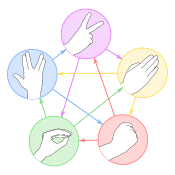

A chart showing how the three game elements interact | |

| Genre(s) | Hand game |

|---|---|

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | None |

| Playing time | Instant |

| Random chance | None |

| Skill(s) required | Psychology |

Rock–paper–scissors (also known as scissors–rock–paper or other variants) is a hand game usually played between two people, in which each player simultaneously forms one of three shapes with an outstretched hand. These shapes are "rock" (a closed fist), "paper" (a flat hand), and "scissors" (a fist with the index finger and middle finger extended, forming a V). "Scissors" is identical to the two-fingered V sign (also indicating "victory" or "peace") except that it is pointed horizontally instead of being held upright in the air. A simultaneous, zero-sum game, it has only two possible outcomes: a draw, or a win for one player and a loss for the other.

A player who decides to play rock will beat another player who has chosen scissors ("rock crushes scissors" or sometimes "blunts scissors"[1]), but will lose to one who has played paper ("paper covers rock"); a play of paper will lose to a play of scissors ("scissors cuts paper"). If both players choose the same shape, the game is tied and is usually immediately replayed to break the tie. The type of game originated in China and spread with increased contact with East Asia, while developing different variants in signs over time. Other names for the game in the English-speaking world include roshambo and other orderings of the three items, with "rock" sometimes being called "stone".[2][3][4]

Rock–paper–scissors is often used as a fair choosing method between two people, similar to coin flipping, drawing straws, or throwing dice in order to settle a dispute or make an unbiased group decision. Unlike truly random selection methods, however, rock–paper–scissors can be played with a degree of skill by recognizing and exploiting non-random behavior in opponents.[5][6]

Contents

Game play[edit]

The players usually count aloud to three, or speak the name of the game (e.g. "Rock! Paper! Scissors!" or "Ro Sham Bo!"), each time either raising one hand in a fist and swinging it down on the count or holding it behind. They then "throw" by extending it towards their opponent. Variations include a version where players use only three counts before throwing their gesture (thus throwing on the count of "Scissors!" or "Bo!"), or a version where they shake their hands three times before "throwing".

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The first known mention of the game was in the book Wuzazu by the Chinese Ming-dynasty writer Xie Zhaozhi (fl. c. 1600), who wrote that the game dated back to the time of the Chinese Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD).[7] In the book, the game was called shoushiling. Li Rihua's book Note of Liuyanzhai also mentions this game, calling it shoushiling (t. 手勢令; s. 手势令), huozhitou (t. 豁指頭; s. 豁指头), or huoquan (豁拳).

%2C_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_from_the_Kensarae_sumai_zue_(1809).jpg/300px-Mushi-ken_(虫拳)%2C_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_from_the_Kensarae_sumai_zue_(1809).jpg)

Throughout Japanese history there are frequent references to sansukumi-ken, meaning ken (fist) games where "the three who are afraid of one another" (i.e. A beats B, B beats C, and C beats A).[8] This type of game originated in China before being imported to Japan and subsequently also becoming popular among the Japanese.[8]

The earliest Japanese sansukumi-ken game was known as mushi-ken (虫拳), which was imported directly from China.[8][9] In mushi-ken the "frog" (represented by the thumb) is superseded by the "slug" (represented by the little finger), which, in turn is superseded by the "snake" (represented by the index finger), which is superseded by the "frog".[8] Although this game was imported from China the Japanese version differs in the animals represented. In adopting the game, the original Chinese characters for the poisonous centipede (蜈蜙) were apparently confused with the characters for the slug (蛞蝓).[9] The most popular sansukumi-ken game in Japan was kitsune-ken (狐拳). In the game, a supernatural fox called a kitsune (狐) defeats the village head, the village head (庄屋) defeats the hunter, and the hunter (猟師) defeats the fox. Kitsune-ken, unlike mushi-ken or rock–paper–scissors, is played by making gestures with both hands.[10]

Today, the best-known sansukumi-ken is called jan-ken (じゃんけん),[9] which is a variation of the Chinese games introduced in the 17th century.[11] Jan-ken uses the rock, paper, and scissors signs[8] and is the game that the modern version of rock–paper–scissors derives from directly.[9] Hand-games using gestures to represent the three conflicting elements of rock, paper, and scissors have been most common since the modern version of the game was created in the late 19th century, between the Edo and Meiji periods.[12]

Spread beyond Asia[edit]

By the early 20th century, rock–paper–scissors had spread beyond Asia, especially through increased Japanese contact with the west.[13] Its English-language name is therefore taken from a translation of the names of the three Japanese hand-gestures for rock, paper and scissors:[14] elsewhere in Asia the open-palm gesture represents "cloth" rather than "paper".[15] The shape of the scissors is also adopted from the Japanese style.[14]

In Britain in 1924 it was described in a letter to The Times as a hand game, possibly of Mediterranean origin, called "zhot".[16] A reader then wrote in to say that the game "zhot" referred to was evidently Jan-ken-pon, which she had often seen played throughout Japan.[17] Although at this date the game appears to have been new enough to British readers to need explaining, the appearance by 1927 of a popular thriller with the title Scissors Cut Paper,[18] followed by Stone Blunts Scissors (1929), suggests it quickly became popular.

In 1927 La Vie au patronage, a children's magazine in France, described it in detail,[19] referring to it as a "jeu japonais" ("Japanese game"). Its French name, "Chi-fou-mi", is based on the Old Japanese words for "one, two, three" ("hi, fu, mi").

A 1932 New York Times article on the Tokyo rush hour describes the rules of the game for the benefit of American readers, suggesting it was not at that time widely known in the U.S.[20] The 1933 edition of the Compton's Pictured Encyclopedia described it as a common method of settling disputes between children in its article on Japan; the name was given as "John Kem Po" and the article pointedly asserted, "This is such a good way of deciding an argument that American boys and girls might like to practice it too."[21]

Strategies[edit]

It is impossible to gain an advantage over a truly random opponent. However, by exploiting the psychological weaknesses of inherently non-random opponents, it is possible to gain a significant advantage.[22][23] Indeed, human players tend to be non-random.[23][24] As a result, there have been programming competitions for algorithms that play rock–paper–scissors.[22][25][26]

During tournaments, players often prepare their sequence of three gestures prior to the tournament's commencement.[27][28] Some tournament players employ tactics to confuse or trick the other player into making an illegal move,[clarification needed] resulting in a loss. One such tactic is to shout the name of one move before throwing another, in order to misdirect and confuse their opponent.[clarification needed]

The "rock" move, in particular, is notable in that it is typically represented by a closed fist—often identical to the fist made by players during the initial countdown. If a player is attempting to beat their opponent based on quickly reading their hand gesture as the players are making their moves, it is possible to determine if the opponent is about to throw "rock" based on their lack of hand movement, as both "scissors" and "paper" require the player to reposition their hand. This can likewise be used to deceive an anticipating opponent by keeping one's fist closed until the last possible moment, leading them to believe that you are about to throw "rock".

Algorithms[edit]

As a consequence of rock–paper–scissors programming contests, many strong algorithms have emerged.[22][25][26] For example, Iocaine Powder, which won the First International RoShamBo Programming Competition in 1999,[25] uses a heuristically designed compilation of strategies.[29] For each strategy it employs, it also has six metastrategies which defeat second-guessing, triple-guessing, as well as second-guessing the opponent, and so on. The optimal strategy or metastrategy is chosen based on past performance. The main strategies it employs are history matching, frequency analysis, and random guessing. Its strongest strategy, history matching, searches for a sequence in the past that matches the last few moves in order to predict the next move of the algorithm. In frequency analysis, the program simply identifies the most frequently played move. The random guess is a fallback method that is used to prevent a devastating loss in the event that the other strategies fail. More than ten years later, the top performing strategies on an ongoing rock–paper–scissors programming competition similarly use metastrategies.[30] However, there have been some innovations, such as using multiple history matching schemes that each match a different aspect of the history – for example, the opponent's moves, the program's own moves, or a combination of both.[30] There have also been other algorithms based on Markov chains.[31]

In 2012, researchers from the Ishikawa Watanabe Laboratory at the University of Tokyo created a robot hand that can play rock–paper–scissors with a 100% win rate. Using a high-speed camera the robot recognizes within one millisecond which shape the human hand is making, then produces the corresponding winning shape.[32][33]

Instances of use in real-life scenarios[edit]

American court case[edit]

In 2006, American federal judge Gregory Presnell from the Middle District of Florida ordered opposing sides in a lengthy court case to settle a trivial (but lengthily debated) point over the appropriate place for a deposition using the game of rock–paper–scissors.[34][35] The ruling in Avista Management v. Wausau Underwriters stated:

Upon consideration of the Motion – the latest in a series of Gordian knots that the parties have been unable to untangle without enlisting the assistance of the federal courts – it is ORDERED that said Motion is DENIED. Instead, the Court will fashion a new form of alternative dispute resolution, to wit: at 4:00 P.M. on Friday, June 30, 2006, counsel shall convene at a neutral site agreeable to both parties. If counsel cannot agree on a neutral site, they shall meet on the front steps of the Sam M. Gibbons U.S. Courthouse, 801 North Florida Ave., Tampa, Florida 33602. Each lawyer shall be entitled to be accompanied by one paralegal who shall act as an attendant and witness. At that time and location, counsel shall engage in one (1) game of "rock, paper, scissors." The winner of this engagement shall be entitled to select the location for the 30(b)(6) deposition to be held somewhere in Hillsborough County during the period 11–12 July 2006.[36]

The public release of this judicial order was seemingly intended to shame the respective law firms regarding their litigation conduct by settling the dispute in a farcical manner.

Auction house selection[edit]

In 2005, when Takashi Hashiyama, CEO of Japanese television equipment manufacturer Maspro Denkoh, decided to auction off the collection of Impressionist paintings owned by his corporation, including works by Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh, he contacted two leading auction houses, Christie's International and Sotheby's Holdings, seeking their proposals on how they would bring the collection to the market as well as how they would maximize the profits from the sale. Both firms made elaborate proposals, but neither was persuasive enough to earn Hashiyama's approval. Unwilling to split up the collection into separate auctions, Hashiyama asked the firms to decide between themselves who would hold the auction, which included Cézanne's Large Trees Under the Jas de Bouffan, worth $12–16 million.

The houses were unable to reach a decision. Hashiyama told the two firms to play rock–paper–scissors to decide who would get the rights to the auction, explaining that "it probably looks strange to others, but I believe this is the best way to decide between two things which are equally good".

The auction houses had a weekend to come up with a choice of move. Christie's went to the 11-year-old twin daughters of the international director of Christie's Impressionist and Modern Art Department Nicholas Maclean, who suggested "scissors" because "Everybody expects you to choose 'rock'." Sotheby's said that they treated it as a game of chance and had no particular strategy for the game, but went with "paper".[38] Christie's won the match and sold the $20 million collection, earning millions of dollars of commission for the auction house.

FA Women's Super League match[edit]

Prior to an 26 October 2018, match in the FA Women's Super League, the referee, upon being without a coin for the pregame coin toss, had the team captains play rock–paper–scissors to determine which team would kick-off. The referee was subsequently suspended for three weeks by The Football Association.[39]

Play by chimpanzees[edit]

In Japan, researchers have taught chimpanzees to play rock–paper–scissors.[40]

Analogues in game design[edit]

In many games, it is common for a group of possible choices to interact in a rock–paper–scissors style, where each selection is strong against a particular choice, but weak against another. Such mechanics can make a game somewhat self-balancing, and prevent gameplay from being overwhelmed by a single dominant strategy.[41]

Many card-based video games in Japan use the rock–paper–scissors system as their core fighting system, with the winner of each round being able to carry out their designated attack. Sega Master System's Alex Kidd in Miracle World has a level where the player has to win a rock-paper-scissors game to go ahead. Others use simple variants of rock–paper–scissors as subgames like Mario Party Advance and Paper Mario: Color Splash.

In Pokémon, there is a rock–paper–scissors element in the type effectiveness system. For example, a Grass-type Pokémon is weak to Fire, Fire is weak to Water, and Water is weak to Grass.[42]

Analogs in nature[edit]

Lizard mating strategies[edit]

The common side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) exhibits a rock–paper–scissors pattern in its mating strategies. Of its three color types of males, "orange beats blue, blue beats yellow, and yellow beats orange" in competition for females, which is similar to the rules of rock-paper-scissors.[43][44]

Bacteria[edit]

Some bacteria also exhibit a rock-paper-scissors dynamic when they engage in antibiotic production. The theory for this finding was demonstrated by computer simulation and in the laboratory by Benjamin Kerr, working at Stanford University with Brendan Bohannan.[45] Additional in vitro results demonstrate rock-paper-scissors dynamics in additional species of bacteria.[46] Biologist Benjamin C. Kirkup, Jr. demonstrated that these antibiotics, bacterioicins, were active as Escherichia coli compete with each other in the intestines of mice, and that the rock-paper-scissors dynamics allowed for the continued competition among strains: antibiotic-producers defeat antibiotic-sensitives; antibiotic-resisters multiply and withstand and out-compete the antibiotic-producers, letting antibiotic-sensitives multiply and out-compete others; until antibiotic-producers multiply again.[47]

Rock–paper–scissors is the subject of continued research in bacterial ecology and evolution. It is considered one of the basic applications of game theory and non-linear dynamics to bacteriology.[48] Models of evolution demonstrate how intragenomic competition can lead to rock-paper-scissors dynamics from a relatively general evolutionary model.[49] The general nature of this basic non-transitive model is widely applied in theoretical biology to explore bacterial ecology and evolution.[50][51]

Analogues in mechanical devices and geometrical constructions[edit]

In televised robot competition "BattleBots", relations between "lifters, which had wedged sides and could use forklift-like prongs to flip pure wedges", "spinners, which were smooth, circular wedges with blades on their bottom side for disabling and breaking lifters", and "pure wedges, which could still flip spinners" are analogical to relations in rock–paper–scissors games and called "robot Darwinism".[52] Also specially designed "rock–paper–scissors game" mechanical devices can demonstrate intransitivity of relations such as "to rotate faster than", "to lift and be not be lifted", "to be stronger than" in some geometrical constructions.[53]

Tournaments[edit]

Various competitive rock–paper–scissors tournaments have been organised by different groups.

World Rock Paper Scissors Society[edit]

Starting in 2002, the World Rock Paper Scissors Society standardized a set of rules for international play[54] and has overseen annual International World Championships. These open, competitive championships have been widely attended by players from around the world and have attracted widespread international media attention.[55][56][57][58][59] WRPS events are noted for their large cash prizes, elaborate staging, and colorful competitors.[60] In 2004, the championships were broadcast on the U.S. television network Fox Sports Net, with the winner being Lee Rammage, who went on to compete in at least one subsequent championship.[61][62] The 2007 tournament was won by Andrea Farina.[63] The last tournament hosted by the World Rock Paper Scissors Society was in Toronto, Canada, on November 14, 2009.[64]

UK championships[edit]

Several RPS events have been organised in the United Kingdom by Wacky Nation. The 1st UK Championship took place on 13 July 2007, and then again on 14 July 2008, in Rhayader, Powys.[citation needed]

The 3rd UK Championships took place on 9 June 2009, in Exeter, Devon. Nick Hemley, from Woking, Surrey, won the contest just beating Chris Grimwood.[65]

The 4th UK Championships took place on 13 November 2010, at the Durell Arms in West London. Paul Lewis from Woking beat Ed Blake in the final and collected the £100 first prize and UK title. Richard Daynes Appreciation Society won the team event. 80 competitors took part in the main contest and 10 entries in the team contest.[citation needed]

The 5th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships took place in London on Saturday 22 October 2011.[66] The event was open to 128 individual competitors. There was also a team contest for 16 teams. The 2011 singles tournament was won by Max Deeley and the team contest won by The Big Faces (Andrew Bladon, Jamie Burland, Tom Wilkinson and Captain Joe Kenny).[67]

The 6th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships[68] took place at Crosse Keys Pub, London on Saturday 13 October 2012 with over 200 competitors.[68]

The 8th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships took place at the Green Man Pub in London on Saturday 4 October 2014, and was won by Dan Tinkler of Leicester.[69]

The 9th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships took place at the Green Man Pub in London on Saturday 4 November 2015, and was won by Loic Zimou of London.[69]

The 10th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships took place at the Green Man Pub in London on Saturday 19 November 2016, and was won by Ronak Kansagra of Ealing.[69]

The 11th UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships took place at the Crutched Friar pub in London on Saturday 18 November 2017.[69]

USARPS tournaments[edit]

USA Rock Paper Scissors League is sponsored by Bud Light. Leo Bryan Pacis was the first commissioner of the USARPS.[citation needed] Cody Louis Brown was elected as the second commissioner of the USARPS in 2014.[citation needed]

In April 2006, the inaugural USARPS Championship was held in Las Vegas. Following months of regional qualifying tournaments held across the US, 257 players were flown to Las Vegas for a single-elimination tournament at the House of Blues where the winner received $50,000. The tournament was shown on the A&E Network on 12 June 2006.

The $50,000 2007 USARPS Tournament took place at the Las Vegas Mandalay Bay in May 2007.

In 2008, Sean "Wicked Fingers" Sears beat 300 other contestants and walked out of the Mandalay Bay Hotel & Casino with $50,000 after defeating Julie "Bulldog" Crossley in the finals.

The inaugural Budweiser International Rock, Paper, Scissors Federation Championship was held in Beijing, China after the close of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games at Club Bud. A Belfast man won the competition.[70]

Team Olimpik Championships 2012[edit]

The international tournament was held in London 2012. UK Champions Team GB (Andrew Bladon, Jamie Burland, Tom Wilkinson and Stephen Preston) went in as overwhelming favorites, but after a "domestic incident" team captain and UK Team Champion Joe Kenny was forced to pull out, allowing Stephen Preston to take his place. Great Britain came a respectable third to achieve the Bronze Medal, while the crowd favorite Vatican City got the Silver and Lapland A took the prestigious Gold Medal. British team captain Tom Wilkinson commented "after a 4-0 whitewash of hot favorites Vatican City we thought we had it. A simple lapse of concentration lost it for us, but we are happy with our bronze medal. We'll come back from this and look to take the title back again next year. The support was immense, and we are thankful of everyone who came out to support us".[71]

National XtremeRPS Competition 2007–2008[edit]

The XtremeRPS National Competition is a US nationwide RPS competition with Preliminary Qualifying contests that started in January 2007 and ended in May 2008, followed by regional finals in June and July 2008. The national finals were to be held in Des Moines, Iowa in August 2008, with a chance to win up to $5,000.

Guinness Book of World Records[edit]

The largest Rock-Paper-Scissors tournament is 2,950 and was achieved by Oomba, Inc. (USA) at Gen Con 2014 in Indianapolis, Indiana, United States, on 17 August 2014.[72]

World Series[edit]

Former Celebrity Poker Showdown host and USARPS Head Referee[73] Phil Gordon has hosted an annual $500 World Series of Rock, Paper, Scissors event in conjunction with the World Series of Poker since 2005.[74] The winner of the WSORPS receives an entry into the WSOP Main Event. The event is an annual fundraiser for the "Cancer Research and Prevention Foundation" via Gordon's charity Bad Beat on Cancer. Poker player Annie Duke won the Second Annual World Series of Rock, Paper, Scissors.[75] The tournament is taped by ESPN and highlights are covered during "The Nuts" section of ESPN's annual WSOP broadcast.[76][77][78] 2009 was the fifth year of the tournament.

Jackpot En Poy of Eat Bulaga![edit]

Jackpot En Poy is a game segment of the Philippines' longest running noontime show, Eat Bulaga!. The game is based on the classic children's game rock–paper–scissors where four players are paired to compete in the three-round segment. In the first round, the first pair plays against each other until one player wins three times. The next pair then plays against each other in the second round. The winners from the first two rounds then compete against each other to finally determine the ultimate winner. The winner of the game then moves on to the final round. In the final round, the player is presented with several Dabarkads, each holding different amounts of cash prize. The player will then pick three Dabarkads who he or she will play rock–paper–scissors against. The player plays against them one at a time. If the player wins against any of the Eat Bulaga! host, he or she will win the cash prize.[79][80][81]

Variations[edit]

%2C_a_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_by_Kikukawa_Eizan_(菊川英山).jpg/220px-Geisha_Playing_the_Hand-Game_Kitsune-ken_(狐拳)%2C_a_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_by_Kikukawa_Eizan_(菊川英山).jpg)

Players have developed numerous cultural and personal variations on the game, from simply playing the same game with different objects, to expanding into more weapons and rules, to giving their own name to the game in their national language.

Adapted rules[edit]

In Korea, a two-player upgraded version exists by the name muk-jji-ppa.[82]

In Japan, a "strip-poker" variant of rock-paper-scissors is known as 野球拳 (Yakyuken). The loser of each round removes an article of clothing. The game is a minor part of porn culture in Japan and other Asian countries after the influence of TV variety shows and Soft On Demand.

In the Philippines, the game is called jak-en-poy, from one of the Japanese names of the game, transliterated as jan-ken-pon. In a longer version of the game, a four-line song is sung, with hand gestures displayed at the end of each (or the final) line: "Jack-en-poy! / Hali-hali-hoy! / Sino'ng matalo, / siya'ng unggoy!" ("Jack-en-poy! / Hali-hali-hoy! / Whoever loses is the monkey!") In the former case, the person with the most wins at the end of the song, wins the game. A shorter version of the game uses the chant "Bato-bato-pick" ("Rock-rock-pick [i.e. choose]") instead.

A multiple player variation can be played: Players stand in a circle and all throw at once. If rock, paper, and scissors are all thrown, it is a stalemate, and they rethrow. If only two throws are present, all players with the losing throw are eliminated. Play continues until only the winner remains.[83]

Different weapons[edit]

In the Malaysian version of the game, "scissors" is replaced by "bird," represented with the finger tips of five fingers brought together to form a beak. The open palm represents water. Bird beats water (by drinking it); stone beats bird (by hitting it); and stone loses to water (because it sinks in it).

Singapore also has a related hand-game called "ji gu pa," where "ji" refers to the bird gesture, "gu" refers to the stone gesture, and "pa" refers to the water gesture. The game is played by two players using both hands. At the same time, they both say, ji gu pa!" At "pa!" they both show two open-palmed hands. One player then changes his hand gestures while calling his new combination out (e.g., "pa gu!"). At the same time, the other player changes his hand gestures as well. If one of his hand gestures is the same as the other one, that hand is "out" and he puts it behind his back; he is no longer able to play that hand for the rest of the round. The players take turns in this fashion, until one player loses by having both hands sent "out." "Ji gu pa" is most likely a transcription of the Japanese names for the different hand gestures in the original jan-ken game, "choki" (scissors), "guu" (rock) and "paa" (paper).

Using the same tripartite division, there is a full-body variation in lieu of the hand signs called "Bear, Hunter, Ninja".[84] In this iteration the participants stand back-to-back and at the count of three (or ro-sham-bo as is traditional) turn around facing each other using their arms evoking one of the totems.[85] The players' choices break down as: Hunter shoots bear; Bear eats ninja; Ninja kills hunter.[86] The game was popularized with a FedEx commercial[87] where warehouse employees had too much free time on their hands.

Additional weapons[edit]

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

As long as the number of moves is an odd number and each move defeats exactly half of the other moves while being defeated by the other half, any combination of moves will function as a game. For example, 5-, 7-, 9-, 11-, 15-, 25-, and 101-weapon versions exist.[88] Adding new gestures has the effect of reducing the odds of a tie, while increasing the complexity of the game. The probability of a tie in an odd-number-of-weapons game can be calculated based on the number of weapons n as 1/n, so the probability of a tie is 1/3 in standard rock-paper-scissors, but 1/5 in a version that offered five moves instead of three.[89]

Similarly, the French game "pierre, papier, ciseaux, puits" (stone, paper, scissors, well) is unbalanced; both the stone and scissors fall in the well and lose to it, while paper covers both stone and well. This means two "weapons", well and paper, can defeat two moves, while the other two weapons each defeat only one of the other three choices. The rock has no advantage to well, so optimal strategy is to play each of the other objects (paper, scissors and well) one third of the time.[90]

One popular five-weapon expansion is "rock-paper-scissors-Spock-lizard", invented by Sam Kass and Karen Bryla,[91] which adds "Spock" and "lizard" to the standard three choices. "Spock" is signified with the Star Trek Vulcan salute, while "lizard" is shown by forming the hand into a sock-puppet-like mouth. Spock smashes scissors and vaporizes rock; he is poisoned by lizard and disproven by paper. Lizard poisons Spock and eats paper; it is crushed by rock and decapitated by scissors. This variant was mentioned in a 2005 article in The Times of London[92] and was later the subject of an episode of the American sitcom The Big Bang Theory in 2008 (as rock-paper-scissors-lizard-Spock).[93]

The majority of such proposed generalizations are isomorphic to a simple game of modular arithmetic, where half the differences are wins for player one. For instance, rock-paper-scissors-Spock-lizard (note the different order of the last two moves) may be modeled as a game in which each player picks a number from one to five. Subtract the number chosen by player two from the number chosen by player one, and then take the remainder modulo 5 of the result. Player one is the victor if the difference is one or three, and player two is the victor if the difference is two or four. If the difference is zero, the game is a tie.

Alternatively, the rankings in rock-paper-scissors-Spock-lizard may be modeled by a comparison of the parity of the two choices. If it is the same (two odd-numbered moves or two even-numbered ones) then the lower number wins, while if they are different (one odd and one even) the higher wins. Using this algorithm, additional moves can easily be added two at a time while keeping the game balanced:

- Declare a move N+1 (where N is the original total of moves) that beats all existing odd-numbered moves and loses to the others (for example, the rock (#1), scissors (#3), and lizard (#5) could fall into the German well (#6), while the paper (#2) covers it and Spock (#4) manipulates it).

- Declare another move N+2 with the reverse property (such as a plant (#7) that grows through the paper (#2), poisons Spock (#4), and grows through the well (#6), while being damaged by the rock (#1), scissors (#3), and lizard (#5)).

See also[edit]

- Chopsticks (hand game)

- Matching pennies, the binary equivalent

- Morra (game), another hand game for deciding trivial matters

- Nontransitive dice

- Rock-paper-scissors and human social cyclic behavior

- Simultaneous action selection

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ Fisher, Len (2008). Rock, Paper, Scissors: Game Theory in Everyday Life. Basic Books. p. 92. ISBN 9780786726936.

- ^ "Game Basics". Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ St. John, Kelly (2003-03-19). "Ready, set ... Roshambo! Contestants vie for $1,000 purse in Rock, Scissors, Paper contest". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ Wells, Steven (2006-11-24). "It's not your dad's ick-ack-ock". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ^ Fisher, Len (2008). Rock, paper, scissors: game theory in everyday life. Basic Books. p. 94. ISBN 9780786726936.

- ^ "How to win at rock-paper-scissors". BBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Moore, Michael E.; Sward, Jennifer (2006). Introduction to the game industry. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-13-168743-1.

- ^ a b c d e Linhart, Sepp (1995). "Some Thoughts on the Ken Game in Japan: From the Viewpoint of Comparative Civilization Studies". Senri Ethnological Studies. 40: 101–124. hdl:10502/750.

- ^ a b c d Linhart, Sepp (1995). "Rituality in the ken game". Ceremony and Ritual in Japan. London: Routledge. pp. 38–41. ISBN 9780415116633.

- ^ Linhart, Sepp (1998). "From Kendo to Jan-ken: The Deterioration of a Game from Exoticism to Ordinariness". The Culture of Japan as Seen through Its Leisure. New York: SUNY Press. pp. 325–326. ISBN 9780791437919.

- ^ Sosnoski, Daniel (2001). Introduction to Japanese culture. Rutland: Tuttle. p. 44. ISBN 9780804820561.

- ^ Linhart, Sepp (1998). Ken no bunkashi. Tokyo: shoten Kadokawa. ISBN 4-04-702103-2.

- ^ Ogawa, Dennis M. (1978). Jan Ken Po: The World of Hawaii's Japanese Americans. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ a b 長田須磨・須山名保子共編 (April 1977). 『奄美方言分類辞典』上巻. Tokyo: Kasama shoin. ASIN B000J8V5WU. Archived from the original on 2015-07-14. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- ^ In Korea the name of the game, Kai Bai Bo, or Kawi Bawi Bo, translates as "scissors, rock, cloth". [1]

- ^ After the Rome correspondent of a British paper described the traditional Italian hand-game of morra, which has some similarities to rock–paper–scissors, a brief correspondence began on the subject. One contributor described a game he had seen played in Mediterranean ports, called 'zot' or 'zhot', which was clearly identical with the modern "Rock–paper–scissors": 'In this game the closed fist represents a stone, the open hand with fingers outstretched paper, and the closed fist with two fingers outstretched scissors...The players stand facing one another, and commence playing simultaneously by raising and lowering the right arm three times rapidly, coming to rest with the fist in any of the three above-mentioned positions. If you keep your fist closed and your opponent flings open his hand then you lose, as paper wraps up stones, and so on.' "The Times". 1 March 1924: 15. Letter to the editor, from Paymaster Lieutenant G.L.P. Garwood, R.N.

- ^ "The Times". 6 March 1924: 8.: Letter to the editor, from Miss F.C.Pringle

- ^ Gerard Fairlie, Scissors Cuts Paper, Hodder and Stoughton, (1927)

- ^ "La Vie au patronage". January 1927: 73.: "Jeux actifs et mi-actifs pouvant être joués en classe."

- ^ New York Times, May 22, 1932 - The New York Times Magazine, article by Marion May Dilts: "COMMUTING WITH TOKYO'S SUBURBANITES; Their Morning Ritual Is Characteristically Japanese, but In Their Mode of Travel There Is Western Technique"

- ^ Compton's Pictured Encyclopedia, 1933, Volume 7, p. 194. F. E. Compton & Company, Chicago

- ^ a b c Knoll, Byron. "Rock Paper Scissors Programming Competition". Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b Morgan, James (2 May 2014). "How to win at rock–paper–scissors". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Dance, Gabriel & Jackson, Tom (2010-10-07). "Rock-Paper-Scissors: You vs. the Computer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b c "First International RoShamBo Programming Competition". 1999-10-01. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b "Second International RoShamBo Programming Competition". 2001-03-20. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ Steve Vockrodt, "Student rivals throw down at rock, paper, scissors tournament", Lawrence Journal-World, 8 April 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ Michael Y. Park, "Rock, Paper, Scissors, the Sport" Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, Fox News, 20 March 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ Egnor, Dan (1999-10-01). "Iocaine Powder Explained". Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b dllu (2011-06-14). "Rock Paper Scissors Programming Competition entry: DNA werfer 5 L500". Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ rfw (2011-05-22). "Rock Paper Scissors Programming Competition entry: sixth-order markov chain". Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ "Rock–paper–scissors robot wins every time – video". The Guardian. London. 2012-06-27.

- ^ "Janken (rock-paper-scissors) robot with 100% winning rate (human-machine cooperation system)". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ "Exasperated judge resorts to child's game". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (2006-06-09). "Lawyers Won't End Squabble, So Judge Turns to Child's Play". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Presnell, Gregory (June 7, 2006). "Order of the court: Avista Management vs. Wausau Underwriters Insurance Co". CNN.com. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ Art/Auctions logo, Impressionist & Modern Art, Christie's, 7 pm, May 4, 2005, Sale 1514.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (April 29, 2005). "Rock, Paper, Payoff: Child's Play Wins Auction House an Art Sale". The New York Times.

- ^ Theisen, Lauren (November 14, 2018). "Soccer Ref Suspended Three Weeks For Using Rock-Paper-Scissors Instead Of Coin Flip". Deadspin. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ "Chimps can play rock-paper-scissors". BBC News. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon; Jonas Heide Smith; Susana Pajares Tosca (2008). Understanding video games: the essential introduction. Taylor & Francis. p. 103. ISBN 0-415-97721-5.

- ^ "Pokemon Go type chart - type strength, weakness and effectiveness for Pokemon battles explained - VG247". 26 June 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Sinervo, Barry (2001-02-20). "The rock-paper-scissors game and the evolution of alternative male strategies". Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ Barry Sinervo on the 7th Avenue Project Radio Show. "The Games Lizards Play".

- ^ Kerr, Benjamin; Riley, Margaret A.; Feldman, Marcus W.; Bohannan, Brendan J. M. (11 July 2002). "Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock–paper–scissors". Nature. 418 (6894): 171–174. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..171K. doi:10.1038/nature00823. PMID 12110887.

- ^ Pátková, Irena; Čepl, Jaroslav J; Rieger, Tomáš; Blahůšková, Anna; Neubauer, Zdeněk; Markoš, Anton (1 January 2012). "Developmental plasticity of bacterial colonies and consortia in germ-free and gnotobiotic settings". BMC Microbiology. 12: 178. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-178.

- ^ Kirkup, Benjamin C.; Riley, Margaret A. (25 March 2004). "Antibiotic-mediated antagonism leads to a bacterial game of rock–paper–scissors in vivo". Nature. 428 (6981): 412–414. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..412K. doi:10.1038/nature02429. PMID 15042087.

- ^ Adami, Christoph; Schossau, Jory; Hintze, Arend (1 January 2012). "Evolution and stability of altruist strategies in microbial games". Physical Review E. 85 (1). arXiv:1012.0276. Bibcode:2012PhRvE..85a1914A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.85.011914.

- ^ Rankin, D. J.; Turner, L. A.; Heinemann, J. A.; Brown, S. P. (11 July 2012). "The coevolution of toxin and antitoxin genes drives the dynamics of bacterial addiction complexes and intragenomic conflict". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1743): 3706–3715. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0942. PMC 3415908. PMID 22787022.

- ^ Bucci, Vanni; Nadell, Carey D.; Xavier, João B. (1 December 2011). "The Evolution of Bacteriocin Production in Bacterial Biofilms". The American Naturalist. 178 (6): E162–E173. doi:10.1086/662668. PMID 22089878.

- ^ Jiang, Luo-Luo; Zhou, Tao; Perc, Matjaž; Wang, Bing-Hong (2011). "Effects of competition on pattern formation in the rock-paper-scissors game" (PDF). Physical Review E. 84 (2). arXiv:1108.1790. Bibcode:2011PhRvE..84b1912J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.84.021912.

- ^ Atherton, K. D. (2013). A brief history of the demise of battle bots. Popular science.

- ^ Poddiakov, A. (2018). Intransitive machines. Cornell University. Series arxive "math". 2018. No. 1809.03869.

- ^ "Game Basics". World Rock Paper Scissors Society. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ Hruby, Patrick (2004-12-10). "Fists fly in game of strategy". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ "2003 World Rock Paper Scissors Championship". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 2003-10-24. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ "Rock, Paper, Scissors A Sport?". CBS News. 2003-10-23. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ "Rock Paper Scissors contest being held". USA Today. Associated Press. 2003-10-27. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ Park, Michael Y. (2006-03-20). "Rock, Paper, Scissors, the Sport". Fox News. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ "Gallery". World RPS society. 2005-11-13. Archived from the original on 2006-03-15. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ^ Crick, Jennifer (2005-06-13). "HAND JIVE - 13 June 2005". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "World RPS Society - 2004 Champion Lee Rammage crushes a pair of Scissors". Stanley-paul.com. 2005-11-13. Retrieved 2009-06-05.[dead link]

- ^ Canoe inc. "Rock Paper Scissors crowns a queen as its champ". canoe.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "World RPS Society World Championships". Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Pub hosts UK 'rock' championship". BBC News. 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ "ukrockpaperscissorschampionships.com". Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived May 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "ukrockpaperscissorschampionships.com". Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d "UK Rock Paper Scissors Championships - Wacky Nation". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Belfast man tops world at rock, paper, scissors | Irish Examiner". Examiner.ie. 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ - Team Olimpik RPS Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Master Rosh's Analysis of the Final Match". USARPS Leagues. USARPS. 2005-06-28. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ Friess, Steven (2007-05-14). "Las Vegas's latest game: Rock, paper, scissors". NY Times. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ "Where's Annie?". ESPN.com. 2006-08-05. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ Caldwell, John (2005-06-15). "The REAL championship at the World Series of Poker". Poker News. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "WSOP Schedule Whiplash". Poker Pages. 2005-06-14. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ Craig, Michael. "EXCLUSIVE COVERAGE: Roshambo — The Rematch". Pokerworks. Archived from the original on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ http://www.gmanetwork.com/entertainment/tv/eat_bulaga/57015/eat-bulaga-judy-ann-santos-tinalo-ang-kapatid-sa-jackpot-en-poy/video/

- ^ "WATCH: PH senators on 'Eat Bulaga'". Rappler. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- ^ Lo, Ricky. "Happily resettled back home". philstar.com. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- ^ "Play muk-zzi-ppa! The upgraded rock-paper-scissors". Hancinema. 2011-06-25. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ^ Walker, Douglas and Graham (2004). The Official Rock paper Scissors Strategy Guide. Bloomington, IN: Simon & Schuster. p. 140. ISBN 0-7432-6751-6.

- ^ "After Another Short Break, "Not Much Equipment Games" returns – Bear, Hunter, Ninja! - Knucklebones". Knucklebones. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Ninja, Hunter, Bear". Inklings. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Pigs Don't Fly by Zac Martin - Digital Marketing & Entrepreneurship: + Bear Hunter Ninja". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AhFbbq0zpHY FedEx Bear, Hunter, Ninja Commercial

- ^ "RPSx".

- ^ Rebecca G. Bettencourt. "Rock Paper Scissors Graphs".

- ^ Umbhauer, Gisèle (2016). Game Theory and Exercises. Routledge. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-3173-6299-9.

- ^ Sam Kass. "Original Rock-Paper-Scissors-Spock-Lizard Page". Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ "... and paper scissors". London: The Times Online. 11 June 2005. Retrieved 2009-06-09.(subscription required)

- ^ Lorre, Chuck. "The Big Bang Theory Video — Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock — CBS.com" (video). CBS. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

Bibliography

- Alonzo, Suzanne H.; Sinervo, Barry (2001). "Mate choice games, context-dependent good genes, and genetic cycles in the side-blotched lizard, Uta stansburiana". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 49 (2–3): 176–186. doi:10.1007/s002650000265.

- Culin, Stewart (1895) Korean Games, With Notes on the Corresponding Games at China and Japan. (evidence of nonexistence of rock-paper-scissors in the West)

- Gomme, Alice Bertha (1894, 1898) The traditional games of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 2 vols. (more evidence of nonexistence of rock-paper-scissors in the West)

- Opie, Iona & Opie, Peter (1969) Children's Games in Street and Playground Oxford University Press, London. (Details some variants on rock-paper-scissors such as 'Man, Earwig, Elephant' in Indonesia, and presents evidence for the existence of 'finger throwing games' in Egypt as early as 2000 B.C.)

- Sinervo, Barry (2001). "Runaway social games, genetic cycles driven by alternative male and female strategies, and the origin of morphs". Genetica. 112–113 (1): 417–434. doi:10.1023/A:1013360426789.

- Sinervo, Barry; Clobert, Jean (2003). "Morphs, Dispersal Behavior, Genetic Similarity, and the Evolution of Cooperation". Science. 300 (5627): 1949–1951. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1949S. doi:10.1126/science.1083109. PMID 12817150.

- Sinervo, Barry; Lively, C. M. (1996). "The Rock-Paper-Scissors Game and the evolution of alternative male strategies". Nature. 380 (6571): 240–243. Bibcode:1996Natur.380..240S. doi:10.1038/380240a0.

- Sinervo, Barry; Zamudio, K. R. (2001). "The Evolution of Alternative Reproductive Strategies: Fitness Differential, Heritability, and Genetic Correlation Between the Sexes". Journal of Heredity. 92 (2): 198–205. doi:10.1093/jhered/92.2.198. PMID 11396579.

- Sogawa, Tsuneo (2000). "Janken". Monthly Sinica (in Japanese). 11 (5).

- Baldwin, Wyatt (2017) The Official Rock Paper Scissors Handbook. The Official Strategy Guide of the World Rock Paper Scissors Association

- Walker, Douglas & Walker, Graham (2004) The Official Rock Paper Scissors Strategy Guide. Fireside. (strategy, tips and culture from the World Rock Paper Scissors Society).

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rock Paper Scissors. |

| Look up じゃんけん in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Abrams, Michael (2004-07-05). "Throwing for The Gold". Pursuits. Forbes FYI. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- Hegan, Ken (2004-01-07). "Hand to Hand Combat: Down and dirty at the World Rock Paper Scissors Championship". Rolling Stone Feature Article. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- A biological example of rock-paper-scissors: Interview with biologist Barry Sinervo on the 7th Avenue Project Radio Show

- The World Rock Paper Scissors Association

- Rock Paper Scissors Programming Competition

- Jenkins, Jolyon. "Rock Paper Scissors". BBC Radio documentary explores links between RPS and game theory. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

.png/100px-Rock-paper-scissors_(rock).png)

.png/100px-Rock-paper-scissors_(paper).png)

.png/100px-Rock-paper-scissors_(scissors).png)

%2C_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_from_the_Genyoku_sui_bento_(1774).jpg/220px-Kitsune-ken_(狐拳)%2C_Japanese_rock-paper-scissors_variant%2C_from_the_Genyoku_sui_bento_(1774).jpg)