Minimalism

This article needs attention from an expert in architecture or arts. The specific problem is: to deal with redundant content, and large tracts of text and in-text lists that are unsourced, and so in violation of WP:VERIFY. (August 2016) |

In visual arts, music, and other mediums, minimalism is an art movement that began in post–World War II Western art, most strongly with American visual arts in the 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with minimalism include Donald Judd, John McCracken, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella.[1][2] It derives from the reductive aspects of modernism and is often interpreted as a reaction against abstract expressionism and a bridge to postminimal art practices.

Minimalism in music often features repetition and gradual variation, such as the works of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Julius Eastman, and John Adams. The term minimalist often colloquially refers to anything that is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has accordingly been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and the automobile designs of Colin Chapman.

Contents

Minimal art, minimalism in visual art[edit]

Minimalism in visual art, generally referred to as "minimal art", "literalist art"[3] and "ABC Art"[4] emerged in New York in the early 1960s as new and older artists moved toward geometric abstraction; exploring via painting in the cases of Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Ryman and others; and sculpture in the works of various artists including David Smith, Anthony Caro, Tony Smith, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and others. Judd's sculpture was showcased in 1964 at Green Gallery in Manhattan, as were Flavin's first fluorescent light works, while other leading Manhattan galleries like Leo Castelli Gallery and Pace Gallery also began to showcase artists focused on geometric abstraction. In addition there were two seminal and influential museum exhibitions: Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculpture shown from April 27 – June 12, 1966 at the Jewish Museum in New York, organized by the museum's Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Kynaston McShine[5][6] and Systemic Painting, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum curated by Lawrence Alloway also in 1966 that showcased Geometric abstraction in the American art world via Shaped canvas, Color Field, and Hard-edge painting.[7][8] In the wake of those exhibitions and a few others the art movement called minimal art emerged.

In a more broad and general sense, one finds European roots of minimalism in the geometric abstractions of painters associated with the Bauhaus, in the works of Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian and other artists associated with the De Stijl movement, and the Russian Constructivist movement, and in the work of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși.[9][10]

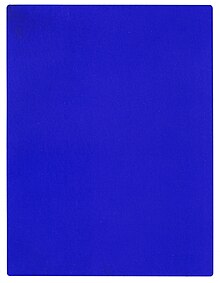

In France between 1947 and 1948,[11] Yves Klein conceived his Monotone Symphony (1949, formally The Monotone-Silence Symphony) that consisted of a single 20-minute sustained chord followed by a 20-minute silence[12][13] – a precedent to both La Monte Young's drone music and John Cage's 4′33″. Klein had painted monochromes as early as 1949, and held the first private exhibition of this work in 1950—but his first public showing was the publication of the Artist's book Yves: Peintures in November 1954.[14][15]

Minimal art is also inspired in part by the paintings of Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, and the works of artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Giorgio Morandi, and others. Minimalism was also a reaction against the painterly subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism that had been dominant in the New York School during the 1940s and 1950s.[16]

Artist and critic Thomas Lawson noted in his 1981 Artforum essay Last Exit: Painting, minimalism did not reject Clement Greenberg's claims about modernist painting's[17] reduction to surface and materials so much as take his claims literally. According to Lawson, minimalism was the result, even though the term "minimalism" was not generally embraced by the artists associated with it, and many practitioners of art designated minimalist by critics did not identify it as a movement as such. Also taking exception to this claim was Clement Greenberg himself; in his 1978 postscript to his essay Modernist Painting he disavowed this interpretation of what he said, writing:

There have been some further constructions of what I wrote that go over into preposterousness: That I regard flatness and the inclosing of flatness not just as the limiting conditions of pictorial art, but as criteria of aesthetic quality in pictorial art; that the further a work advances the self-definition of an art, the better that work is bound to be. The philosopher or art historian who can envision me—or anyone at all—arriving at aesthetic judgments in this way reads shockingly more into himself or herself than into my article.[17]

In contrast to the previous decade's more subjective Abstract Expressionists, with the exceptions of Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt; minimalists were also influenced by composers John Cage and LaMonte Young, poet William Carlos Williams, and the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. They very explicitly stated that their art was not about self-expression, and unlike the previous decade's more subjective philosophy about art making theirs was 'objective'. In general, minimalism's features included geometric, often cubic forms purged of much metaphor, equality of parts, repetition, neutral surfaces, and industrial materials.

Robert Morris, a theorist and artist, wrote a three part essay, "Notes on Sculpture 1–3", originally published across three issues of Artforum in 1966. In these essays, Morris attempted to define a conceptual framework and formal elements for himself and one that would embrace the practices of his contemporaries. These essays paid great attention to the idea of the gestalt – "parts... bound together in such a way that they create a maximum resistance to perceptual separation." Morris later described an art represented by a "marked lateral spread and no regularized units or symmetrical intervals..." in "Notes on Sculpture 4: Beyond Objects", originally published in Artforum, 1969, continuing on to say that "indeterminacy of arrangement of parts is a literal aspect of the physical existence of the thing." The general shift in theory of which this essay is an expression suggests the transition into what would later be referred to as postminimalism.

One of the first artists specifically associated with minimalism was the painter Frank Stella, four of whose early "black paintings" were included in the 1959 show, 16 Americans, organized by Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The width of the stripes in Frank Stellas's black paintings were often determined by the dimensions of the lumber he used for stretchers to support the canvas, visible against the canvas as the depth of the painting when viewed from the side. Stella's decisions about structures on the front surface of the canvas were therefore not entirely subjective, but pre-conditioned by a "given" feature of the physical construction of the support. In the show catalog, Carl Andre noted, "Art excludes the unnecessary. Frank Stella has found it necessary to paint stripes. There is nothing else in his painting." These reductive works were in sharp contrast to the energy-filled and apparently highly subjective and emotionally charged paintings of Willem de Kooning or Franz Kline and, in terms of precedent among the previous generation of abstract expressionists, leaned more toward the less gestural, often somber, color field paintings of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Stella received immediate attention from the MoMA show, but other artists—including Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis, Robert Motherwell, and Robert Ryman—had also begun to explore stripes, monochromatic and Hard-edge formats from the late 50s through the 1960s.[18]

Because of a tendency in minimal art to exclude the pictorial, illusionistic and fictive in favor of the literal, there was a movement away from painterly and toward sculptural concerns. Donald Judd had started as a painter, and ended as a creator of objects. His seminal essay, "Specific Objects" (published in Arts Yearbook 8, 1965), was a touchstone of theory for the formation of minimalist aesthetics. In this essay, Judd found a starting point for a new territory for American art, and a simultaneous rejection of residual inherited European artistic values. He pointed to evidence of this development in the works of an array of artists active in New York at the time, including Jasper Johns, Dan Flavin and Lee Bontecou. Of "preliminary" importance for Judd was the work of George Earl Ortman,[19] who had concretized and distilled painting's forms into blunt, tough, philosophically charged geometries. These Specific Objects inhabited a space not then comfortably classifiable as either painting or sculpture. That the categorical identity of such objects was itself in question, and that they avoided easy association with well-worn and over-familiar conventions, was a part of their value for Judd.

This movement was criticized by modernist formalist art critics and historians. Some critics thought minimal art represented a misunderstanding of the modern dialectic of painting and sculpture as defined by critic Clement Greenberg, arguably the dominant American critic of painting in the period leading up to the 1960s. The most notable critique of minimalism was produced by Michael Fried, a formalist critic, who objected to the work on the basis of its "theatricality". In Art and Objecthood (published in Artforum in June 1967) he declared that the minimal work of art, particularly minimal sculpture, was based on an engagement with the physicality of the spectator. He argued that work like Robert Morris's transformed the act of viewing into a type of spectacle, in which the artifice of the act observation and the viewer's participation in the work were unveiled. Fried saw this displacement of the viewer's experience from an aesthetic engagement within, to an event outside of the artwork as a failure of minimal art. Fried's essay was immediately challenged by postminimalist and earth artist Robert Smithson in a letter to the editor in the October issue of Artforum. Smithson stated the following: "What Fried fears most is the consciousness of what he is doing—namely being himself theatrical."

In addition to the already mentioned Robert Morris, Frank Stella, Carl Andre, Robert Ryman and Donald Judd other minimal artists include: Robert Mangold, Larry Bell, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Charles Hinman, Ronald Bladen, Paul Mogensen, Ronald Davis, David Novros, Brice Marden, Blinky Palermo, Agnes Martin, Jo Baer, John McCracken, Ad Reinhardt, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra, Tony Smith, Patricia Johanson, and Anne Truitt.

Ad Reinhardt, actually an artist of the Abstract Expressionist generation, but one whose reductive nearly all-black paintings seemed to anticipate minimalism, had this to say about the value of a reductive approach to art:

The more stuff in it, the busier the work of art, the worse it is. More is less. Less is more. The eye is a menace to clear sight. The laying bare of oneself is obscene. Art begins with the getting rid of nature.[20]

Reinhardt's remark directly addresses and contradicts Hans Hofmann's regard for nature as the source of his own abstract expressionist paintings. In a famous exchange between Hofmann and Jackson Pollock as told by Lee Krasner in an interview with Dorothy Strickler[21] (1964-11-02) for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art.[22] In Krasner's words:

When I brought Hofmann up to meet Pollock and see his work which was before we moved here, Hofmann’s reaction was—one of the questions he asked Jackson was, "Do you work from nature?" There were no still lifes around or models around and Jackson’s answer was, "I am nature." And Hofmann’s reply was, "Ah, but if you work by heart, you will repeat yourself." To which Jackson did not reply at all. The meeting between Pollock and Hofmann took place in 1942.[22]

Minimalist design and architecture[edit]

This section possibly contains original research. (May 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

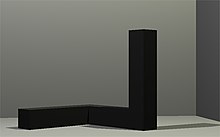

The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture, wherein the subject is reduced to its necessary elements.[citation needed] Minimalist architectural designers focus on the connection between two perfect planes, elegant lighting, and the void spaces left by the removal of three-dimensional shapes in an architectural design.[according to whom?][citation needed]

Minimalistic design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture.[citation needed] The works of De Stijl artists are a major reference: De Stijl expanded the ideas of expression by meticulously organizing basic elements such as lines and planes.[citation needed] With regard to home design, more attractive "minimalistic" designs are not truly minimalistic because they are larger, and use more expensive building materials and finishes.[citation needed]

There are observers who describe the emergence of minimalism as a response to the brashness and chaos of urban life. In Japan, for example, minimalist architecture began to gain traction in the 1980s when its cities experienced rapid expansion and booming population. The design was considered an antidote to the "overpowering presence of traffic, advertising, jumbled building scales, and imposing roadways."[23] The chaotic environment was not only driven by urbanization, industrialization, and technology but also the Japanese experience of constantly having to demolish structures on account of the destruction wrought by World War II and the earthquakes, including the calamities it entails such as fire. The minimalist design philosophy did not arrive in Japan by way of another country as it was already part of the Japanese culture rooted on the Zen philosophy. There are those who specifically attribute the design movement to Japan's spirituality and view of nature.[24]

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) adopted the motto "Less is more" to describe his aesthetic.[25] His tactic was one of arranging the necessary components of a building to create an impression of extreme simplicity—he enlisted every element and detail to serve multiple visual and functional purposes; for example, designing a floor to also serve as the radiator, or a massive fireplace to also house the bathroom. Designer Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) adopted the engineer's goal of "Doing more with less", but his concerns were oriented toward technology and engineering rather than aesthetics.[26]

Luis Barragán is an exemplary modern minimalist designer.[according to whom?][citation needed] Other contemporary minimalist architects include Kazuyo Sejima, John Pawson, Eduardo Souto de Moura, Álvaro Siza Vieira, Tadao Ando, Alberto Campo Baeza, Yoshio Taniguchi, Peter Zumthor, Hugh Newell Jacobsen, Vincent Van Duysen, Claudio Silvestrin, Michael Gabellini, and Richard Gluckman.[27][page needed][verification needed]

Minimalist architecture and space[edit]

Minimalist architecture became popular in the late 1980s in London and New York,[28] where architects and fashion designers worked together in the boutiques to achieve simplicity, using white elements, cold lighting, large space with minimum objects and furniture.

Concepts and design elements[edit]

The concept of minimalist architecture is to strip everything down to its essential quality and achieve simplicity.[29] The idea is not completely without ornamentation,[30] but that all parts, details, and joinery are considered as reduced to a stage where no one can remove anything further to improve the design.[31]

The considerations for ‘essences’ are light, form, detail of material, space, place, and human condition.[32] Minimalist architects not only consider the physical qualities of the building. They consider the spiritual dimension and the invisible, by listening to the figure and paying attention to details, people, space, nature, and materials.,[33] believing this reveals the abstract quality of something that is invisible and aids the search for the essence of those invisible qualities—such as natural light, sky, earth, and air. In addition, they "open a dialogue" with the surrounding environment to decide the most essential materials for the construction and create relationships between buildings and sites.[30]

In minimalist architecture, design elements strive to convey the message of simplicity. The basic geometric forms, elements without decoration, simple materials and the repetitions of structures represent a sense of order and essential quality.[34] The movement of natural light in buildings reveals simple and clean spaces.[32] In the late 19th century as the arts and crafts movement became popular in Britain, people valued the attitude of ‘truth to materials’ with respect to the profound and innate characteristics of materials.[35] Minimalist architects humbly 'listen to figure,' seeking essence and simplicity by rediscovering the valuable qualities in simple and common materials.[33]

Influences from Japanese tradition[edit]

The idea of simplicity appears in many cultures, especially the Japanese traditional culture of Zen Philosophy. Japanese manipulate the Zen culture into aesthetic and design elements for their buildings.[37] This idea of architecture has influenced Western Society, especially in America since the mid 18th century.[38] Moreover, it inspired the minimalist architecture in the 19th century.[31]

Zen concepts of simplicity transmit the ideas of freedom and essence of living.[31] Simplicity is not only aesthetic value, it has a moral perception that looks into the nature of truth and reveals the inner qualities and essence of materials and objects.[39] For example, the sand garden in Ryoanji temple demonstrates the concepts of simplicity and the essentiality from the considered setting of a few stones and a huge empty space.[40]

The Japanese aesthetic principle of Ma refers to empty or open space. It removes all the unnecessary internal walls and opens up the space. The emptiness of spatial arrangement reduces everything down to the most essential quality.[41]

The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-sabi values the quality of simple and plain objects.[42] It appreciates the absence of unnecessary features, treasures a life in quietness and aims to reveal the innate character of materials.[43] For example, the Japanese floral art, also known as Ikebana, has the central principle of letting the flower express itself. People cut off the branches, leaves and blossoms from the plants and only retain the essential part of the plant. This conveys the idea of essential quality and innate character in nature.[44]

However, far from being just a spatial concept, Ma is ever-present in all aspects of Japanese daily life, as it applies to time as well as to daily tasks.[45]

Minimalist architects and their works[edit]

The Japanese minimalist architect, Tadao Ando conveys the Japanese traditional spirit and his own perception of nature in his works. His design concepts are materials, pure geometry and nature. He normally uses concrete or natural wood and basic structural form to achieve austerity and rays of light in space. He also sets up dialogue between the site and nature to create relationship and order with the buildings.[46] Ando's works and the translation of Japanese aesthetic principles are highly influential on Japanese architecture.[47]

Another Japanese minimalist architect, Kazuyo Sejima, works on her own and in conjunction with Ryue Nishizawa, as SANAA, producing iconic Japanese Minimalist buildings. Credited with creating and influencing a particular genre of Japanese Minimalism,[48] Sejimas delicate, intelligent designs may use white color, thin construction sections and transparent elements to create the phenomenal building type often associated with minimalism. Works include New Museum(2010) New York City, Small House (2000) Tokyo, House surrounded By Plum Trees (2003) Tokyo.

In Vitra Conference Pavilion, Weil am Rhein, 1993, the concepts are to bring together the relationships between building, human movement, site and nature. Which as one main point of minimalism ideology that establish dialogue between the building and site. The building uses the simple forms of circle and rectangle to contrast the filled and void space of the interior and nature. In the foyer, there is a large landscape window that looks out to the exterior. This achieves the simple and silence of architecture and enhances the light, wind, time and nature in space.[49]

John Pawson is a British minimalist architect; his design concepts are soul, light, and order. He believes that though reduced clutter and simplification of the interior to a point that gets beyond the idea of essential quality, there is a sense of clarity and richness of simplicity instead of emptiness. The materials in his design reveal the perception toward space, surface, and volume. Moreover, he likes to use natural materials because of their aliveness, sense of depth and quality of an individual. He is also attracted by the important influences from Japanese Zen Philosophy.[50]

Calvin Klein Madison Avenue, New York, 1995–96, is a boutique that conveys Calvin Klein's ideas of fashion. John Pawson's interior design concepts for this project are to create simple, peaceful and orderly spatial arrangements. He used stone floors and white walls to achieve simplicity and harmony for space. He also emphasises reduction and eliminates the visual distortions, such as the air conditioning and lamps to achieve a sense of purity for interior.[51]

Alberto Campo Baeza is a Spanish architect and describes his work as essential architecture. He values the concepts of light, idea and space. Light is essential and achieves the relationship between inhabitants and the building. Ideas are to meet the function and context of space, forms, and construction. Space is shaped by the minimal geometric forms to avoid decoration that is not essential.[52]

Gasper House, Zahora, 1992 is a residence that the client wanted to be independent. High walls create the enclosed space and the stone floors used in house and courtyard show the continuality of interior and exterior. The white colour of the walls reveals the simplicity and unity of the building. The feature of the structure make lines to form the continuously horizontal house, therefore natural light projects horizontally through the building.[53]

Literary minimalism[edit]

Literary minimalism is characterized by an economy with words and a focus on surface description. Minimalist writers eschew adverbs and prefer allowing context to dictate meaning. Readers are expected to take an active role in creating the story, to "choose sides" based on oblique hints and innuendo, rather than react to directions from the writer.

Some 1940s-era crime fiction of writers such as James M. Cain and Jim Thompson adopted a stripped-down, matter-of-fact prose style to considerable effect; some classify this prose style as minimalism.[weasel words]

Another strand of literary minimalism arose in response to the metafiction trend of the 1960s and early 1970s (John Barth, Robert Coover, and William H. Gass). These writers were also spare with prose and kept a psychological distance from their subject matter.[citation needed]

Minimalist writers, or those who are identified with minimalism during certain periods of their writing careers, include the following: Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Bret Easton Ellis, Charles Bukowski, Ernest Hemingway, K. J. Stevens, Amy Hempel, Bobbie Ann Mason, Tobias Wolff, Grace Paley, Sandra Cisneros, Mary Robison, Frederick Barthelme, Richard Ford, Patrick Holland, Cormac McCarthy, and Alicia Erian.[citation needed]

American poets such as Stephen Crane, William Carlos Williams, early Ezra Pound, Robert Creeley, Robert Grenier, and Aram Saroyan are sometimes identified with their minimalist style. The term "minimalism" is also sometimes associated with the briefest of poetic genres, haiku, which originated in Japan, but has been domesticated in English literature by poets such as Nick Virgilio, Raymond Roseliep, and George Swede.[citation needed]

The Irish writer Samuel Beckett is well known for his minimalist plays and prose, as is the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse.[54]

In his novel The Easy Chain, Evan Dara includes a 60-page section written in the style of musical minimalism, in particular inspired by composer Steve Reich. Intending to represent the psychological state (agitation) of the novel's main character, the section's successive lines of text are built on repetitive and developing phrases.[citation needed]

Minimal music[edit]

The term "minimal music" was derived around 1970 by Michael Nyman from the concept of minimalism, which was earlier applied to the visual arts.[55][56] More precisely, it was in a 1968 review in The Spectator that Nyman first used the term, to describe a ten-minute piano composition by the Danish composer Henning Christiansen, along with several other unnamed pieces played by Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.[57]

Minimalism in film[edit]

The term usually is associated with filmmakers such as Robert Bresson, Carl Theodor Dreyer and Yasujirō Ozu. Their films typically tell a simple story with straight forward camera usage and minimal use of score. Paul Schrader named their kind of cinema: "transcendental cinema".[58] Abbas Kiarostami is also considered a creater of minimalistic films.

See also[edit]

This "see also" section may contain an excessive number of suggestions. Please ensure that only the most relevant links are given, that they are not red links, and that any links are not already in this article. (March 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Abstract Imagists

- Capsule wardrobe

- Formalism (art)

- Geometric abstraction

- KISS principle

- Kmart realism

- List of minimalist artists

- Lyrical abstraction

- Maximalism

- Minimal techno

- Minimalism (computing)

- Modular constructivism

- Monochrome painting

- Neo-minimalism

- Postminimalism

- Shaped canvas

- Simple living

- Zero (art)

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "Christopher Want, Minimalism, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009". Moma.org. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Minimalism". theartstory.org. 2012.

- ^ Fried, M. "Art and Objecthood", Artforum, 1967

- ^ Rose, Barbara. "ABC Art", Art in America 53, no. 5 (October–November 1965): 57–69.

- ^ Time magazine, June 3, 1966, "Engineer's Esthetic", pg. 64

- ^ Newsweek magazine, May 16, 1966, "The New Druids", pg. 104

- ^ "Systemic Painting, Guggenheim Museum". Guggenheim.org. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Systemic art, Oxford-Art encyclopedia". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Maureen Mullarkey, Art Critical, Giorgio Morandi". Artcritical.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ Daniel Marzona, Uta Grosenick; Minimal art, p.12. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Yves Klein (1928–1962)". documents/biography. Yves Klein Archives & McDourduff. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Gilbert Perlein & Bruno Corà (eds) & al., Yves Klein: Long Live the Immaterial! ("An anthological retrospective", catalog of an exhibition held in 2000), New York: Delano Greenidge, 2000, ISBN 978-0-929445-08-3, p. 226: "This symphony, 40 minutes in length (in fact 20 minutes followed by 20 minutes of silence) is constituted of a single 'sound' stretched out, deprived of its attack and end which creates a sensation of vertigo, whirling the sensibility outside time."

- ^ See also at YvesKleinArchives.org a 1998 sound excerpt of The Monotone Symphony Archived 2008-12-08 at the Wayback Machine (Flash plugin required), its short description Archived 2008-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, and Klein's "Chelsea Hotel Manifesto" Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine (including a summary of the 2-part Symphony).

- ^ Hannah Weitemeier, Yves Klein, 1928–1962: International Klein Blue, Original-Ausgabe (Cologne: Taschen, 1994), 15. ISBN 3-8228-8950-4.

- ^ "Restoring the Immaterial: Study and Treatment of Yves Klein's Blue Monochrome (IKB42)". Modern Paint Uncovered.

- ^ Gregory Battcock, Minimal Art: a critical anthology, pp 161–172. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Britannica.com". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ Oisteanu, Valery (2006-12-08). "Brooklynrail.org". Brooklynrail.org. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ in Barbara Rose, ed. Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt (New York: Viking Press, 1975):[page needed] ISBN 978-0-520-07670-9.

- ^ Archives of American Art. "Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1964 Nov. 2-1968 Apr. 11 – Oral Histories | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". Aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ a b Archives of American Art. "Lee Krasner, Archives of American Art". Aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ Ostwald, Michael; Vaughan, Josephine (2016). The Fractal Dimension of Architecture. Newcastle: Birkhauser. p. 316. ISBN 9783319324241.

- ^ Cerver, Francisco (1997). The Architecture of Minimalism. Arco. p. 13. ISBN 9780823061495.

- ^ See Philip Johnson, op. cit. A similar sentiment was conveyed by industrial designer Dieter Rams' motto, "Less but better."[citation needed]

- ^ Philip Johnson, Mies van der Rohe, Museum of Modern Art, 1947, p. 49

- ^ Holm, Ivar (2006). Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the built environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 82-547-0174-1.[page needed]

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b Rossell (2005), Minimalist Interiors, New York: HapperCollins. p6.

- ^ a b c Pawson (1996), Minimum, London: Phaidon Press Limited. p7.

- ^ a b Bertoni 2002, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Bertoni 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Pawson (1996), Minimum, London: Phaidon Press Limited. p8.

- ^ Saito, (Winter 2007), The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1. P.87–88.

- ^ 森神逍遥 『侘び然び幽玄のこころ』桜の花出版、2015年 Morigami Shouyo, "Wabi sabi yugen no kokoro: seiyo tetsugaku o koeru joi ishiki" (Japanese) ISBN 978-4434201424

- ^ Saito, (Winter 2007), The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1. p.85–97.

- ^ Lancaster (September 1953), Japanese Buildings in the United States before 1900: Their Influence upon American Domestic Architecture, The Art Bulletin, vol. 35, no. 3. p217–224.

- ^ Saito, (Winter 2007), The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1. p87.

- ^ Pawson (1996), Minimum, London: Phaidon Press Limited. p98.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Saito, (Winter 2007), The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1. p85.

- ^ Pawson (1996), Minimum, London: Phaidon Press Limited. p10–11.

- ^ Saito, (Winter 2007), The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1.p86.

- ^ "When Less is More: the Concept of Japanese "MA"". Wawaza.com. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, pp. 96–106.

- ^ Cerver 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Puglisi, L.P. (2008), New Directions in Contermporary Architecture, Chichester, John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 18–29.

- ^ Pawson (1996), Minimum, London: Phaidon Press Limited. p10-14.

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 170–77.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 182.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 192.

- ^ Davies, Paul. "Samuel Beckett". Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Bernard, Jonathan W. (1993). "The Minimalist Aesthetic in the Plastic Arts and in Music". Perspectives of New Music. 31 (1 (Winter)): 87. JSTOR 833043., citing Dan Warburton as his authority.

- ^ Warburton, Dan. "A Working Terminology for Minimal Music". Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Nyman 1968, 519.

- ^ Paul Schrader on Revisiting Transcendental Style in Film | TIFF 2017|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4F8I8OVmUU

References[edit]

- Bertoni, Franco (2002). Minimalist Architecture, edited by Franco Cantini, translated from the Italian by Lucinda Byatt and from the Spanish by Paul Hammond. Basel, Boston, and Berlin: Birkhäuser. ISBN 3-7643-6642-7.

- Carlos, Espartaco (1989). Eduardo Sanguinetti: The Experience of Limits. Buenos Aires: Ediciones de Arte Gaglianone. ISBN 950-9004-98-7.

- Cerver, Francisco Asencio (1997). The Architecture of Minimalism. New York: Arco. ISBN 0-8230-6149-3.

- Keenan, David, and Michael Nyman (2001). "Claim to Frame". The Sunday Herald (4 February).

- Lancaster, Clay (September 1953). "Japanese Buildings in the United States before 1900: Their Influence upon American Domestic Architecture". The Art Bulletin, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 217–224.

- Nyman, Michael (1968). "Minimal Music". The Spectator 221, no. 7320 (11 October): 518–19.

- Pawson, John (1996). Minimum. London: Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 0-7148-3262-6.

- Rossell, Quim (2005). Minimalist Interiors. New York: Collins Design. ISBN 0-688-17487-6 (cloth); ISBN 0-06-082990-7 (cloth).

- Saito, Yuriko (2007). "The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.65, no. 1 (Winter), pp. 85–97. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minimalism. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Minimalism |