Determinism

| Part of a series on |

| Certainty |

|---|

|

Related concepts and fundamentals: |

Determinism is the philosophical idea that all events, including moral choices, are determined completely by previously existing causes. Determinism is at times understood to preclude free will because it entails that humans cannot act otherwise than they do. It can also be called as hard determinism from this point of view. Hard determinism is a position on the relationship of determinism to free will. The theory holds that the universe is utterly rational because complete knowledge of any given situation assures that unerring knowledge of its future is also possible.[1] Some philosophers suggest variants around this basic definition.[2] Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have sprung from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. The opposite of determinism is some kind of indeterminism (otherwise called nondeterminism). Determinism is often contrasted with free will.[3][4]

Determinism often is taken to mean causal determinism, which in physics is known as cause-and-effect. It is the concept that events within a given paradigm are bound by causality in such a way that any state (of an object or event) is completely determined by prior states. This meaning can be distinguished from other varieties of determinism mentioned below.

Other debates often concern the scope of determined systems, with some maintaining that the entire universe is a single determinate system and others identifying other more limited determinate systems (or multiverse). Numerous historical debates involve many philosophical positions and varieties of determinism. They include debates concerning determinism and free will, technically denoted as compatibilistic (allowing the two to coexist) and incompatibilistic (denying their coexistence is a possibility). Determinism should not be confused with self-determination of human actions by reasons, motives, and desires. Determinism rarely requires that perfect prediction be practically possible.

Contents

Varieties[edit]

"Determinism" may commonly refer to any of the following viewpoints:

- Causal determinism is "the idea that every event is necessitated by antecedent events and conditions together with the laws of nature".[5] However, causal determinism is a broad enough term to consider that "one's deliberations, choices, and actions will often be necessary links in the causal chain that brings something about. In other words, even though our deliberations, choices, and actions are themselves determined like everything else, it is still the case, according to causal determinism, that the occurrence or existence of yet other things depends upon our deliberating, choosing and acting in a certain way".[6] Causal determinism proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. The relation between events may not be specified, nor the origin of that universe. Causal determinists believe that there is nothing in the universe that is uncaused or self-caused. Historical determinism (a sort of path dependence) can also be synonymous with causal determinism. Causal determinism has also been considered more generally as the idea that everything that happens or exists is caused by antecedent conditions.[7] In the case of nomological determinism, these conditions are considered events also, implying that the future is determined completely by preceding events—a combination of prior states of the universe and the laws of nature.[5] Yet they can also be considered metaphysical of origin (such as in the case of theological determinism).[6]

- Nomological determinism is the most common form of causal determinism. It is the notion that the past and the present dictate the future entirely and necessarily by rigid natural laws, that every occurrence results inevitably from prior events. Nomological determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon.[8] Nomological determinism is sometimes called 'scientific' determinism, although that is a misnomer. Physical determinism is generally used synonymously with nomological determinism (its opposite being physical indeterminism).

- Necessitarianism is closely related to the causal determinism described above. It is a metaphysical principle that denies all mere possibility; there is exactly one way for the world to be. Leucippus claimed there were no uncaused events, and that everything occurs for a reason and by necessity.[9]

- Predeterminism is the idea that all events are determined in advance.[10][11] The concept of predeterminism is often argued by invoking causal determinism, implying that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. In the case of predeterminism, this chain of events has been pre-established, and human actions cannot interfere with the outcomes of this pre-established chain. Predeterminism can be used to mean such pre-established causal determinism, in which case it is categorised as a specific type of determinism.[10][12] It can also be used interchangeably with causal determinism—in the context of its capacity to determine future events.[10][13] Despite this, predeterminism is often considered as independent of causal determinism.[14][15] The term predeterminism is also frequently used in the context of biology and hereditary, in which case it represents a form of biological determinism.[16]

- Fatalism is normally distinguished from "determinism",[17] as a form of teleological determinism. Fatalism is the idea that everything is fated to happen, so that humans have no control over their future. Fate has arbitrary power, and need not follow any causal or otherwise deterministic laws.[7] Types of fatalism include hard theological determinism and the idea of predestination, where there is a God who determines all that humans will do. This may be accomplished either by knowing their actions in advance, via some form of omniscience[18] or by decreeing their actions in advance.[19]

- Theological determinism is a form of determinism that holds that all events that happen are pre-ordained, or predestined to happen, by a monotheistic deity, or that they are destined to occur given its omniscience. Two forms of theological determinism exist, here referenced as strong and weak theological determinism.[20] The first one, strong theological determinism, is based on the concept of a creator deity dictating all events in history: "everything that happens has been predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent divinity".[21] The second form, weak theological determinism, is based on the concept of divine foreknowledge—"because God's omniscience is perfect, what God knows about the future will inevitably happen, which means, consequently, that the future is already fixed".[22] There exist slight variations on the above categorisation. Some claim that theological determinism requires predestination of all events and outcomes by the divinity (i.e. they do not classify the weaker version as 'theological determinism' unless libertarian free will is assumed to be denied as a consequence), or that the weaker version does not constitute 'theological determinism' at all.[23] With respect to free will, "theological determinism is the thesis that God exists and has infallible knowledge of all true propositions including propositions about our future actions", more minimal criteria designed to encapsulate all forms of theological determinism.[24] Theological determinism can also be seen as a form of causal determinism, in which the antecedent conditions are the nature and will of God.[6] Augustine of Hippo introduced theological determinism into Christianity in 412 CE, whereas all prior Christian authors supported free will against Stoic and Gnostic determinism.[25]

- Logical determinism or Determinateness is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or future, are either true or false. Note that one can support causal determinism without necessarily supporting logical determinism and vice versa (depending on one's views on the nature of time, but also randomness). The problem of free will is especially salient now with logical determinism: how can choices be free, given that propositions about the future already have a truth value in the present (i.e. it is already determined as either true or false)? This is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Adequate determinism focuses on the fact that, even without a full understanding of microscopic physics, we can predict the distribution of 1000 coin tosses.

Adequate determinism focuses on the fact that, even without a full understanding of microscopic physics, we can predict the distribution of 1000 coin tosses.- Often synonymous with logical determinism are the ideas behind spatio-temporal determinism or eternalism: the view of special relativity. J. J. C. Smart, a proponent of this view, uses the term "tenselessness" to describe the simultaneous existence of past, present, and future. In physics, the "block universe" of Hermann Minkowski and Albert Einstein assumes that time is a fourth dimension (like the three spatial dimensions). In other words, all the other parts of time are real, like the city blocks up and down a street, although the order in which they appear depends on the driver (see Rietdijk–Putnam argument).

- Adequate determinism is the idea that quantum indeterminacy can be ignored for most macroscopic events. This is because of quantum decoherence. Random quantum events "average out" in the limit of large numbers of particles (where the laws of quantum mechanics asymptotically approach the laws of classical mechanics).[26] Stephen Hawking explains a similar idea: he says that the microscopic world of quantum mechanics is one of determined probabilities. That is, quantum effects rarely alter the predictions of classical mechanics, which are quite accurate (albeit still not perfectly certain) at larger scales.[27] Something as large as an animal cell, then, would be "adequately determined" (even in light of quantum indeterminacy).

- The many-worlds interpretation accepts the linear causal sets of sequential events with adequate consistency yet also suggests constant forking of causal chains creating "multiple universes" to account for multiple outcomes from single events.[28] Meaning the causal set of events leading to the present are all valid yet appear as a singular linear time stream within a much broader unseen conic probability field of other outcomes that "split off" from the locally observed timeline. Under this model causal sets are still "consistent" yet not exclusive to singular iterated outcomes. The interpretation side steps the exclusive retrospective causal chain problem of "could not have done otherwise" by suggesting "the other outcome does exist" in a set of parallel universe time streams that split off when the action occurred. This theory is sometimes described with the example of agent based choices but more involved models argue that recursive causal splitting occurs with all particle wave functions at play.[29] This model is highly contested with multiple objections from the scientific community.

Philosophical connections[edit]

With nature/nurture controversy[edit]

Although some of the above forms of determinism concern human behaviors and cognition, others frame themselves as an answer to the debate on nature and nurture. They will suggest that one factor will entirely determine behavior. As scientific understanding has grown, however, the strongest versions of these theories have been widely rejected as a single-cause fallacy.[30]

In other words, the modern deterministic theories attempt to explain how the interaction of both nature and nurture is entirely predictable. The concept of heritability has been helpful in making this distinction.

Biological determinism, sometimes called genetic determinism, is the idea that each of human behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by human genetic nature.

Behaviorism involves the idea that all behavior can be traced to specific causes—either environmental or reflexive. John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner developed this nurture-focused determinism.

Cultural determinism or social determinism is the nurture-focused theory that the culture in which we are raised determines who we are.

Environmental determinism, also known as climatic or geographical determinism, proposes that the physical environment, rather than social conditions, determines culture. Supporters of environmental determinism often[quantify] also support Behavioral determinism. Key proponents of this notion have included Ellen Churchill Semple, Ellsworth Huntington, Thomas Griffith Taylor and possibly Jared Diamond, although his status as an environmental determinist is debated.[31]

With particular factors[edit]

Other 'deterministic' theories actually seek only to highlight the importance of a particular factor in predicting the future. These theories often use the factor as a sort of guide or constraint on the future. They need not suppose that complete knowledge of that one factor would allow us to make perfect predictions.

Psychological determinism can mean that humans must act according to reason, but it can also be synonymous with some sort of Psychological egoism. The latter is the view that humans will always act according to their perceived best interest.

Linguistic determinism claims that our language determines (at least limits) the things we can think and say and thus know. The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis argues that individuals experience the world based on the grammatical structures they habitually use.

Economic determinism attributes primacy to economic structure over politics in the development of human history. It is associated with the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx.

Technological determinism is a reductionist theory that presumes that a society's technology drives the development of its social structure and cultural values.

With free will[edit]

Philosophers have debated both the truth of determinism, and the truth of free will. This creates the four possible positions in the figure. Compatibilism refers to the view that free will is, in some sense, compatible with determinism. The three incompatibilist positions, on the other hand, deny this possibility. The hard incompatibilists hold that both determinism and free will do not exist, the libertarianists that determinism does not hold, and free will might exist, and the hard determinists that determinism does hold and free will does not exist.

The Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza was a determinist thinker, and argued that human freedom can be achieved through knowledge of the causes that determine our desire and affections. He defined human servitude as the state of bondage of the man who is aware of his own desires, but ignorant of the causes that determined him. On the other hand, the free or virtuous man becomes capable, through reason and knowledge, to be genuinely free, even as he is being "determined". For the Dutch philosopher, acting out of our own internal necessity is genuine freedom while being driven by exterior determinations is akin to bondage. Spinoza's thoughts on human servitude and liberty are respectively detailed in the fourth [32] and fifth [33] volumes of his work of art Ethics.

The standard argument against free will, according to philosopher J. J. C. Smart, focuses on the implications of determinism for 'free will'.[34] However, he suggests free will is denied whether determinism is true or not. On one hand, if determinism is true, all our actions are predicted and we are assumed not to be free; on the other hand, if determinism is false, our actions are presumed to be random and as such we do not seem free because we had no part in controlling what happened.

In his book, The Moral Landscape, author and neuroscientist Sam Harris also argues against free will. He offers one thought experiment where a mad scientist represents determinism. In Harris' example, the mad scientist uses a machine to control all the desires, and thus all the behavior, of a particular human. Harris believes that it is no longer as tempting, in this case, to say the victim has "free will". Harris says nothing changes if the machine controls desires at random - the victim still seems to lack free will. Harris then argues that we are also the victims of such unpredictable desires (but due to the unconscious machinations of our brain, rather than those of a mad scientist). Based on this introspection, he writes "This discloses the real mystery of free will: if our experience is compatible with its utter absence, how can we say that we see any evidence for it in the first place?"[35] adding that "Whether they are predictable or not, we do not cause our causes."[36] That is, he believes there is compelling evidence of absence of free will.

With the soul[edit]

Some determinists argue that materialism does not present a complete understanding of the universe, because while it can describe determinate interactions among material things, it ignores the minds or souls of conscious beings.

A number of positions can be delineated:

- Immaterial souls are all that exist (Idealism).

- Immaterial souls exist and exert a non-deterministic causal influence on bodies. (Traditional free-will, interactionist dualism).[37][38]

- Immaterial souls exist, but are part of deterministic framework.

- Immaterial souls exist, but exert no causal influence, free or determined (epiphenomenalism, occasionalism)

- Immaterial souls do not exist — there is no mind-body dichotomy, and there is a Materialistic explanation for intuitions to the contrary.

With ethics and morality[edit]

Another topic of debate is the implication that Determinism has on morality. Hard determinism (a belief in determinism, and not free will) is particularly criticized for seeming to make traditional moral judgments impossible. Some philosophers, however, find this an acceptable conclusion.

Philosopher and incompatibilist Peter van Inwagen introduces this thesis as such:

Argument that Free Will is Required for Moral Judgments

- The moral judgment that you shouldn't have done X implies that you should have done something else instead

- That you should have done something else instead implies that there was something else for you to do

- That there was something else for you to do implies that you could have done something else

- That you could have done something else implies that you have free will

- If you don't have free will to have done other than X we cannot make the moral judgment that you shouldn't have done X.[39]

However, a compatibilist might have an issue with Inwagen's process because one can not change the past like his arguments center around. A compatibilist who centers around plans for the future might posit:

- The moral judgment that you should not have done X implies that you can do something else instead

- That you can do something else instead implies that there is something else for you to do

- That there is something else for you to do implies that you can do something else

- That you can do something else implies that you have free will for planning future recourse

- If you have free will to do other than X we can make the moral judgment that you should do other than X, and punishing you as a responsible party for having done X that you know you should not have done can help you remember to not do X in the future.

History[edit]

Determinism was developed by the Greek philosophers during the 7th and 6th centuries BC by the Pre-socratic philosophers Heraclitus and Leucippus, later Aristotle, and mainly by the Stoics. Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyám, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, more recently, John Searle, Sam Harris, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett.

Mecca Chiesa notes that the probabilistic or selectionistic determinism of B.F. Skinner comprised a wholly separate conception of determinism that was not mechanistic at all. Mechanistic determinism assumes that every event has an unbroken chain of prior occurrences, but a selectionistic or probabilistic model does not.[40][41]

Western tradition[edit]

In the West, some elements of determinism have been expressed in Greece from the 6th century BC by the Presocratics Heraclitus[42] and Leucippus.[43] The first full-fledged notion of determinism appears to originate with the Stoics, as part of their theory of universal causal determinism.[44] The resulting philosophical debates, which involved the confluence of elements of Aristotelian Ethics with Stoic psychology, led in the 1st-3rd centuries CE in the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias to the first recorded Western debate over determinism and freedom,[45] an issue that is known in theology as the paradox of free will. The writings of Epictetus as well as Middle Platonist and early Christian thought were instrumental in this development.[46] The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides said of the deterministic implications of an omniscient god:[47] "Does God know or does He not know that a certain individual will be good or bad? If thou sayest 'He knows', then it necessarily follows that [that] man is compelled to act as God knew beforehand he would act, otherwise God's knowledge would be imperfect.…"[48]

Determinism in the West is often associated with Newtonian physics, which depicts the physical matter of the universe as operating according to a set of fixed, knowable laws. The "billiard ball" hypothesis, a product of Newtonian physics, argues that once the initial conditions of the universe have been established, the rest of the history of the universe follows inevitably. If it were actually possible to have complete knowledge of physical matter and all of the laws governing that matter at any one time, then it would be theoretically possible to compute the time and place of every event that will ever occur (Laplace's demon). In this sense, the basic particles of the universe operate in the same fashion as the rolling balls on a billiard table, moving and striking each other in predictable ways to produce predictable results.

Whether or not it is all-encompassing in so doing, Newtonian mechanics deals only with caused events, e.g.: If an object begins in a known position and is hit dead on by an object with some known velocity, then it will be pushed straight toward another predictable point. If it goes somewhere else, the Newtonians argue, one must question one's measurements of the original position of the object, the exact direction of the striking object, gravitational or other fields that were inadvertently ignored, etc. Then, they maintain, repeated experiments and improvements in accuracy will always bring one's observations closer to the theoretically predicted results. When dealing with situations on an ordinary human scale, Newtonian physics has been so enormously successful that it has no competition. But it fails spectacularly as velocities become some substantial fraction of the speed of light and when interactions at the atomic scale are studied. Before the discovery of quantum effects and other challenges to Newtonian physics, "uncertainty" was always a term that applied to the accuracy of human knowledge about causes and effects, and not to the causes and effects themselves.

Newtonian mechanics as well as any following physical theories are results of observations and experiments, and so they describe "how it all works" within a tolerance. However, old western scientists believed if there are any logical connections found between an observed cause and effect, there must be also some absolute natural laws behind. Belief in perfect natural laws driving everything, instead of just describing what we should expect, led to searching for a set of universal simple laws that rule the world. This movement significantly encouraged deterministic views in western philosophy,[49] as well as the related theological views of Classical Pantheism.

Eastern tradition[edit]

This section possibly contains original research. (December 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The idea that the entire universe is a deterministic system has been articulated in both Eastern and non-Eastern religion, philosophy, and literature.

In I Ching and Philosophical Taoism, the ebb and flow of favorable and unfavorable conditions suggests the path of least resistance is effortless (see wu wei).

In the philosophical schools of India, the concept of precise and continual effect of laws of Karma on the existence of all sentient beings is analogous to western deterministic concept. Karma is the concept of "action" or "deed" in Indian religions. It is understood as that which causes the entire cycle of cause and effect (i.e., the cycle called saṃsāra) originating in ancient India and treated in Hindu, Jain, and Sikh. Karma is considered predetermined and deterministic in the universe, and in combination with the decisions (free will) of living beings, accumulates to determine futuristic situations that the living being encounters. See Karma in Hinduism.[citation needed]

Modern scientific perspective[edit]

Generative processes[edit]

Although it was once thought by scientists that any indeterminism in quantum mechanics occurred at too small a scale to influence biological or neurological systems, there is indication that nervous systems are influenced by quantum indeterminism due to chaos theory[citation needed]. It is unclear what implications this has for the problem of free will given various possible reactions to the problem in the first place.[50] Many biologists don't grant determinism: Christof Koch argues against it, and in favour of libertarian free will, by making arguments based on generative processes (emergence).[51] Other proponents of emergentist or generative philosophy, cognitive sciences and evolutionary psychology, argue that a certain form of determinism (not necessarily causal) is true.[52][53][54][55] They suggest instead that an illusion of free will is experienced due to the generation of infinite behaviour from the interaction of finite-deterministic set of rules and parameters. Thus the unpredictability of the emerging behaviour from deterministic processes leads to a perception of free will, even though free will as an ontological entity does not exist.[52][53][54][55] Certain experiments looking at the neuroscience of free will can be said to support this possibility.[citation needed]

As an illustration, the strategy board-games chess and Go have rigorous rules in which no information (such as cards' face-values) is hidden from either player and no random events (such as dice-rolling) happen within the game. Yet, chess and especially Go with its extremely simple deterministic rules, can still have an extremely large number of unpredictable moves. When chess is simplified to 7 or fewer pieces, however, endgame tables are available that dictate which moves to play to achieve a perfect game. This implies that, given a less complex environment (with the original 32 pieces reduced to 7 or fewer pieces), a perfectly predictable game of chess is possible. In this scenario, the winning player can announce that a checkmate will happen within a given number of moves, assuming a perfect defense by the losing player, or fewer moves if the defending player chooses sub-optimal moves as the game progresses into its inevitable, predicted conclusion. By this analogy, it is suggested, the experience of free will emerges from the interaction of finite rules and deterministic parameters that generate nearly infinite and practically unpredictable behavioural responses. In theory, if all these events could be accounted for, and there were a known way to evaluate these events, the seemingly unpredictable behaviour would become predictable.[52][53][54][55] Another hands-on example of generative processes is John Horton Conway's playable Game of Life.[56] Nassim Taleb is wary of such models, and coined the term "ludic fallacy".

Compatibility with the existence of science[edit]

Certain philosophers of science argue that, while causal determinism (in which everything including the brain/mind is subject to the laws of causality) is compatible with minds capable of science, fatalism and predestination is not. These philosophers make the distinction that causal determinism means that each step is determined by the step before and therefore allows sensory input from observational data to determine what conclusions the brain reaches, while fatalism in which the steps between do not connect an initial cause to the results would make it impossible for observational data to correct false hypotheses. This is often combined with the argument that if the brain had fixed views and the arguments were mere after-constructs with no causal effect on the conclusions, science would have been impossible and the use of arguments would have been a meaningless waste of energy with no persuasive effect on brains with fixed views.[57]

Mathematical models[edit]

Many mathematical models of physical systems are deterministic. This is true of most models involving differential equations (notably, those measuring rate of change over time). Mathematical models that are not deterministic because they involve randomness are called stochastic. Because of sensitive dependence on initial conditions, some deterministic models may appear to behave non-deterministically; in such cases, a deterministic interpretation of the model may not be useful due to numerical instability and a finite amount of precision in measurement. Such considerations can motivate the consideration of a stochastic model even though the underlying system is governed by deterministic equations.[58][59][60]

Quantum and Classical Mechanics[edit]

Day-to-day physics[edit]

Since the beginning of the 20th century, quantum mechanics—the physics of the extremely small—has revealed previously concealed aspects of events. Before that, Newtonian physics—the physics of everyday life—dominated. Taken in isolation (rather than as an approximation to quantum mechanics), Newtonian physics depicts a universe in which objects move in perfectly determined ways. At the scale where humans exist and interact with the universe, Newtonian mechanics remain useful, and make relatively accurate predictions (e.g. calculating the trajectory of a bullet). But whereas in theory, absolute knowledge of the forces accelerating a bullet would produce an absolutely accurate prediction of its path, modern quantum mechanics casts reasonable doubt on this main thesis of determinism.

Relevant is the fact that certainty is never absolute in practice (and not just because of David Hume's problem of induction). The equations of Newtonian mechanics can exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions. This is an example of the butterfly effect, which is one of the subjects of chaos theory. The idea is that something even as small as a butterfly could cause a chain reaction leading to a hurricane years later. Consequently, even a very small error in knowledge of initial conditions can result in arbitrarily large deviations from predicted behavior. Chaos theory thus explains why it may be practically impossible to predict real life, whether determinism is true or false. On the other hand, the issue may not be so much about human abilities to predict or attain certainty as much as it is the nature of reality itself. For that, a closer, scientific look at nature is necessary.

Quantum realm[edit]

Quantum physics works differently in many ways from Newtonian physics. Physicist Aaron D. O'Connell explains that understanding our universe, at such small scales as atoms, requires a different logic than day-to-day life does. O'Connell does not deny that it is all interconnected: the scale of human existence ultimately does emerge from the quantum scale. O'Connell argues that we must simply use different models and constructs when dealing with the quantum world.[61] Quantum mechanics is the product of a careful application of the scientific method, logic and empiricism. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is frequently confused with the observer effect. The uncertainty principle actually describes how precisely we may measure the position and momentum of a particle at the same time — if we increase the accuracy in measuring one quantity, we are forced to lose accuracy in measuring the other. "These uncertainty relations give us that measure of freedom from the limitations of classical concepts which is necessary for a consistent description of atomic processes."[62]

This is where statistical mechanics come into play, and where physicists begin to require rather unintuitive mental models: A particle's path simply cannot be exactly specified in its full quantum description. "Path" is a classical, practical attribute in our every day life, but one that quantum particles do not meaningfully possess. The probabilities discovered in quantum mechanics do nevertheless arise from measurement (of the perceived path of the particle). As Stephen Hawking explains, the result is not traditional determinism, but rather determined probabilities.[63] In some cases, a quantum particle may indeed trace an exact path, and the probability of finding the particles in that path is one (certain to be true). In fact, as far as prediction goes, the quantum development is at least as predictable as the classical motion, but the key is that it describes wave functions that cannot be easily expressed in ordinary language. As far as the thesis of determinism is concerned, these probabilities, at least, are quite determined. These findings from quantum mechanics have found many applications, and allow us to build transistors and lasers. Put another way: personal computers, Blu-ray players and the internet all work because humankind discovered the determined probabilities of the quantum world.[64] None of that should be taken to imply that other aspects of quantum mechanics are not still up for debate.

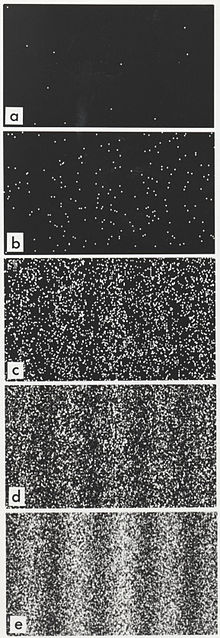

On the topic of predictable probabilities, the double-slit experiments are a popular example. Photons are fired one-by-one through a double-slit apparatus at a distant screen. Curiously, they do not arrive at any single point, nor even the two points lined up with the slits (the way you might expect of bullets fired by a fixed gun at a distant target). Instead, the light arrives in varying concentrations at widely separated points, and the distribution of its collisions with the target can be calculated reliably. In that sense the behavior of light in this apparatus is deterministic, but there is no way to predict where in the resulting interference pattern any individual photon will make its contribution (although, there may be ways to use weak measurement to acquire more information without violating the Uncertainty principle).

Some (including Albert Einstein) argue that our inability to predict any more than probabilities is simply due to ignorance.[65] The idea is that, beyond the conditions and laws we can observe or deduce, there are also hidden factors or "hidden variables" that determine absolutely in which order photons reach the detector screen. They argue that the course of the universe is absolutely determined, but that humans are screened from knowledge of the determinative factors. So, they say, it only appears that things proceed in a merely probabilistically determinative way. In actuality, they proceed in an absolutely deterministic way.

John S. Bell criticized Einstein's work in his famous Bell's Theorem, which proved that quantum mechanics can make statistical predictions that would be violated if local hidden variables really existed. A number of experiments have tried to verify such predictions, and so far they do not appear to be violated. Improved continue to verify the result, including the 2015 "Loophole Free Test" that plugged all known sources of error and the 2017 "Cosmic Bell Test" that based the experiment cosmic data streaming from different directions toward the Earth, precluding the possibility the sources of data could have had prior interactions. However, it is possible to augment quantum mechanics with non-local hidden variables to achieve a deterministic theory that is in agreement with experiment.[66] An example is the Bohm interpretation of quantum mechanics. Bohm's Interpretation, though, violates special relativity and it is highly controversial whether or not it can be reconciled without giving up on determinism.

More advanced variations on these arguments include Quantum contextuality, by Bell, Simon B. Kochen and Ernst Specker in which argues that hidden variable theories cannot be "sensible," which here means that the values of the hidden variables inherently depend on the devices used to measure them.

This debate is relevant because it is easy to imagine specific situations in which the arrival of an electron at a screen at a certain point and time would trigger one event, whereas its arrival at another point would trigger an entirely different event (e.g. see Schrödinger's cat - a thought experiment used as part of a deeper debate).

Thus, quantum physics casts reasonable doubt on the traditional determinism of classical, Newtonian physics in so far as reality does not seem to be absolutely determined. This was the subject of the famous Bohr–Einstein debates between Einstein and Niels Bohr and there is still no consensus.[67][68]

Adequate determinism (see Varieties, above) is the reason that Stephen Hawking calls Libertarian free will "just an illusion".[63] see Free will for further discussions on this topic.

Other matters of quantum determinism[edit]

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

All uranium found on earth is thought to have been synthesized during a supernova explosion that occurred roughly 5 billion years ago. Even before the laws of quantum mechanics were developed to their present level, the radioactivity of such elements has posed a challenge to determinism due to its unpredictability. One gram of uranium-238, a commonly occurring radioactive substance, contains some 2.5 x 1021 atoms. Each of these atoms are identical and indistinguishable according to all tests known to modern science. Yet about 12600 times a second, one of the atoms in that gram will decay, giving off an alpha particle. The challenge for determinism is to explain why and when decay occurs, since it does not seem to depend on external stimulus. Indeed, no extant theory of physics makes testable predictions of exactly when any given atom will decay. At best scientists can discover determined probabilities in the form of the element's half life.

The time dependent Schrödinger equation gives the first time derivative of the quantum state. That is, it explicitly and uniquely predicts the development of the wave function with time.

So if the wave function itself is reality (rather than probability of classical coordinates), then the unitary evolution of the wave function in quantum mechanics, can be said to be deterministic. But the unitary evolution of the wave function is not the entirety of quantum mechanics.

Asserting that quantum mechanics is deterministic by treating the wave function itself as reality might be thought to imply a single wave function for the entire universe, starting at the origin of the universe. Such a "wave function of everything" would carry the probabilities of not just the world we know, but every other possible world that could have evolved. For example, large voids in the distributions of galaxies are believed by many cosmologists to have originated in quantum fluctuations during the big bang. (See cosmic inflation, primordial fluctuations and large-scale structure of the cosmos.)

However, neither the posited reality nor the proven and extraordinary accuracy of the wave function and quantum mechanics at small scales can imply or reasonably suggest the existence of a single wave function for the entire universe. Quantum mechanics breaks down wherever gravity becomes significant, because nothing in the wave function, or in quantum mechanics, predicts anything at all about gravity. And this is obviously of great importance on larger scales.

Gravity is thought of as a large-scale force, with a longer reach than any other. But gravity becomes significant even at masses that are tiny compared to the mass of the universe.

A wave function the size of the universe might successfully model a universe with no gravity. Our universe, with gravity, is vastly different from what quantum mechanics alone predicts. To forget this is a colossal error.

Objective collapse theories, which involve a dynamic (and non-deterministic) collapse of the wave function (e.g. Ghirardi–Rimini–Weber theory, Penrose interpretation, or causal fermion systems) avoid these absurdities. The theory of causal fermion systems for example, is able to unify quantum mechanics, general relativity and quantum field theory, via a more fundamental theory that is non-linear, but gives rise to the linear behaviour of the wave function and also gives rise to the non-linear, non-deterministic, wave-function collapse. These theories suggest that a deeper understanding of the theory underlying quantum mechanics shows the universe is indeed non-deterministic at a fundamental level.

See also[edit]

- Amor fati

- Calvinism

- Causality

- Chaos theory

- Digital physics

- Emergence

- Eternalism

- False necessity

- Fatalism

- Fractal

- Game theory

- Ilya Prigogine

- Interpretation of quantum mechanics

- Lazy reason

- Many-Worlds interpretation

- Neuroscience of free will

- Notes from Underground

- Open theism

- Predestination

- Philosophical interpretation of classical physics

- Radical behaviorism

- Voluntarism

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

Types of determinism[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Determinism Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ A list of a dozen varieties of determinism is provided in Bob Doyle (2011). Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy. I-Phi Press. pp. 145–146 ff. ISBN 0983580200.

- ^ For example, see Richard Langdon Franklin (1968). Freewill and determinism: a study of rival conceptions of man. Routledge & K. Paul.

- ^ Conceptually (20 January 2019). "Determinism - Explanation and examples". conceptually.org. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b Hoefer, Carl (Apr 1, 2008). "Causal Determinism". In Edward N. Zalta, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2009 edition).CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link)

- ^ a b c Eshleman, Andrew (Nov 18, 2009). "Moral Responsibility". In Edward N. Zalta, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2009 ed.).CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link)

- ^ a b Arguments for Incompatibilism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^

Laplace posited that an omniscient observer knowing with infinite precision all the positions and velocities of every particle in the universe could predict the future entirely. For a discussion, see Robert C. Solomon; Kathleen M. Higgins (2009). "Free will and determinism". The Big Questions: A Short Introduction to Philosophy (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 232. ISBN 0495595152. Another view of determinism is discussed by Ernest Nagel (1999). "§V: Alternative descriptions of physical state". The Structure of Science: Problems in the Logic of Scientific Explanation (2nd ed.). Hackett. pp. 285–292. ISBN 0915144719.

a theory is deterministic if, and only if, given its state variables for some initial period, the theory logically determines a unique set of values for those variables for any other period.

- ^ Leucippus, Fragment 569 - from Fr. 2 Actius I, 25, 4

- ^ a b c McKewan, Jaclyn (2009). "Evolution, Chemical". In H. James Birx". Predeterminism. Encyclopedia of Time: Science, Philosophy, Theology, & Culture. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 1035–1036. doi:10.4135/9781412963961.n191. ISBN 9781412941648.

- ^ "Predeterminism". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2012.. See also "Predeterminism". Collins English Dictionary. Collins. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Some Varieties of Free Will and Determinism". Philosophy 302: Ethics. philosophy.lander.edu. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

Predeterminism: the philosophical and theological view that combines God with determinism. On this doctrine events throughout eternity have been foreordained by some supernatural power in a causal sequence.

- ^ See for example Hooft, G. (2001). "How does god play dice? (Pre-)determinism at the Planck scale". arXiv:hep-th/0104219.

Predeterminism is here defined by the assumption that the experimenter's 'free will' in deciding what to measure (such as his choice to measure the x- or the y-component of an electron's spin), is in fact limited by deterministic laws, hence not free at all

, and Sukumar, CV (1996). "A new paradigm for science and architecture". City. Taylor & Francis. 1 (1–2): 181–183. doi:10.1080/13604819608900044.Quantum Theory provided a beautiful description of the behaviour of isolated atoms and nuclei and small aggregates of elementary particles. Modern science recognized that predisposition rather than predeterminism is what is widely prevalent in nature.

- ^ Borst, C. (1992). "Leibniz and the compatibilist account of free will". Studia leibnitiana: 49–58. JSTOR 40694201.

Leibniz presents a clear case of a philosopher who does not think that predeterminism requires universal causal determinism

- ^ Far Western Philosophy of Education Society (1971). Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Far Western Philosophy of Education Society. Far Western Philosophy of Education Society. p. 12. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

"Determinism" is, in essence, the position which holds that all behavior is caused by prior behavior. "Predeterminism" is the position which holds that all behavior is caused by conditions which predate behavior altogether (such impersonal boundaries as "the human conditions", instincts, the will of God, inherent knowledge, fate, and such).

- ^ "Predeterminism". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 20 December 2012. See for example Ormond, A.T. (1894). "Freedom and psycho-genesis". Psychological Review. Macmillan & Company. 1 (3): 217–229. doi:10.1037/h0065249.

The problem of predeterminism is one that involves the factors of heredity and environment, and the point to be debated here is the relation of the present self that chooses to these predetermining agencies

, and Garris, M.D.; et al. (1992). "A Platform for Evolving Genetic Automata for Text Segmentation (GNATS)". Science of Artificial Neural Networks. Science of Artificial Neural Networks. Citeseer. 1710: 714–724. doi:10.1117/12.140132.However, predeterminism is not completely avoided. If the codes within the genotype are not designed properly, then the organisms being evolved will be fundamentally handicapped.

- ^ SEP, Causal Determinism

- ^ Fischer, John Martin (1989) God, Foreknowledge and Freedom. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 1-55786-857-3

- ^ Watt, Montgomery (1948) Free-Will and Predestination in Early Islam. London:Luzac & Co.

- ^ Anne Lockyer Jordan; Anne Lockyer Jordan Neil Lockyer Edwin Tate; Neil Lockyer; Edwin Tate (25 June 2004). Philosophy of Religion for A Level OCR Edition. Nelson Thornes. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-7487-8078-5. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ A. Pabl Iannone (2001). "determinism". Dictionary of World Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-415-17995-9. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

theological determinism, or the doctrine of predestination: the view that everything which happens has been predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent divinity. A weaker version holds that, though not predestined to happen, everything that happens has been eternally known by virtue of the divine foreknowledge of an omniscient divinity. If this divinity is also omnipotent, as in the case of the Judeo-Christian religions, this weaker version is hard to distinguish from the previous one because, though able to prevent what happens and knowing that it is going to happen, God lets it happen. To this, advocates of free will reply that God permits it to happen in order to make room for the free will of humans.

- ^ Wentzel Van Huyssteen (2003). "theological determinism". Encyclopedia of science and religion. 1. Macmillan Reference. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-02-865705-9. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

Theological determinism constitutes a fifth kind of determinism. There are two types of theological determinism, both compatible with scientific and metaphysical determinism. In the first, God determines everything that happens, either in one all-determining single act at the initial creation of the universe or through continuous divine interactions with the world. Either way, the consequence is that everything that happens becomes God's action, and determinism is closely linked to divine action and God's omnipotence. According to the second type of theological determinism, God has perfect knowledge of everything in the universe because God is omniscient. And, as some say, because God is outside of time, God has the capacity of knowing past, present, and future in one instance. This means that God knows what will happen in the future. And because God's omniscience is perfect, what God knows about the future will inevitably happen, which means, consequently, that the future is already fixed.

- ^ Raymond J. VanArragon (21 October 2010). Key Terms in Philosophy of Religion. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4411-3867-5. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

Theological determinism, on the other hand, claims that all events are determined by God. On this view, God decree that everything will go thus-and-so and ensure that everything goes that way, so that ultimately God is the cause of everything that happens and everything that happens is part of God's plan. We might think of God here as the all-powerful movie director who writes script and causes everything to go accord with it. We should note, as an aside, that there is some debate over what would be sufficient for theological determinism to be true. Some people claim that God's merely knowing what will happen determines that it will, while others believe that God must not only know but must also cause those events to occur in order for their occurrence to be determined.

- ^ Vihvelin, Kadri (2011). "Arguments for Incompatibilism". In Edward N. Zalta. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2011 ed.).

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth (2018). Augustine's Conversion from Traditional Free Choice to "Non-free Free Will": A Comprehensive Methodology in the series Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum 111. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 273–298. ISBN 9783161557538.

- ^ The Information Philosopher website, "Adequate Determinism", from the site: "We are happy to agree with scientists and philosophers who feel that quantum effects are for the most part negligible in the macroscopic world. We particularly agree that they are negligible when considering the causally determined will and the causally determined actions set in motion by decisions of that will."

- ^ Grand Design (2010), page 32: "the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets.", and page 72: "Quantum physics might seem to undermine the idea that nature is governed by laws, but that is not the case. Instead it leads us to accept a new form of determinism: Given the state of a system at some time, the laws of nature determine the probabilities of various futures and pasts rather than determining the future and past with certainty." (emphasis in original, discussing a Many worlds interpretation)

- ^ Kent, Adrian. "One world versus many: the inadequacy of Everettian accounts of evolution, probability, and scientific confirmation." Many worlds (2010): 307–354.

- ^ Vaidman, Lev. "Many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics." (2002).

- ^ de Melo-Martín I (2005). "Firing up the nature/nurture controversy: bioethics and genetic determinism". J Med Ethics. 31 (9): 526–30. doi:10.1136/jme.2004.008417. PMC 1734214. PMID 16131554.

- ^ Andrew, Sluyter (2003). "Neo-Environmental Determinism, Intellectual Damage Control, and Nature/Society Science". Antipode. 35 (4): 813–817. doi:10.1046/j.1467-8330.2003.00354.x.

- ^ "Human infirmity in moderating and checking the emotions I name bondage: for, when a man is a prey to his emotions, he is not his own master, but lies at the mercy of fortune: so much so, that he is often compelled, while seeing that which is better for him, to follow that which is worse." - Ethics, Book IV, Preface

- ^ "At length I pass to the remaining portion of my Ethics, which is concerned with the way leading to freedom. I shall therefore treat therein of the power of the reason, showing how far the reason can control the emotions, and what is the nature of Mental Freedom or Blessedness ; we shall then be able to see, how much more powerful the wise man is than the ignorant." Ethics, book V, Preface

- ^ J. J. C. Smart, "Free-Will, Praise and Blame,"Mind, July 1961, p.293-4.

- ^ Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape (2010), pg.216, note102

- ^ Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape (2010), pg.217, note109

- ^ By 'soul' in the context of (1) is meant an autonomous immaterial agent that has the power to control the body but not to be controlled by the body (this theory of determinism thus conceives of conscious agents in dualistic terms). Therefore the soul stands to the activities of the individual agent's body as does the creator of the universe to the universe. The creator of the universe put in motion a deterministic system of material entities that would, if left to themselves, carry out the chain of events determined by ordinary causation. But the creator also provided for souls that could exert a causal force analogous to the primordial causal force and alter outcomes in the physical universe via the acts of their bodies. Thus, it emerges that no events in the physical universe are uncaused. Some are caused entirely by the original creative act and the way it plays itself out through time, and some are caused by the acts of created souls. But those created souls were not created by means of physical processes involving ordinary causation. They are another order of being entirely, gifted with the power to modify the original creation. However, determinism is not necessarily limited to matter; it can encompass energy as well. The question of how these immaterial entities can act upon material entities is deeply involved in what is generally known as the mind-body problem. It is a significant problem which philosophers have not reached agreement about

- ^ Free Will (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ van Inwagen, Peter (2009). The Powers of Rational Beings: Freedom of the Will. Oxford.

- ^ Chiesa, Mecca (2004) Radical Behaviorism: The Philosophy & The Science.

- ^ Ringen, J. D. (1993). "Adaptation, teleology, and selection by consequences". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 60 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1901/jeab.1993.60-3. PMC 1322142. PMID 16812698.

- ^ Stobaeus Eclogae I 5 (Heraclitus)

- ^ Stobaeus Eclogae I 4 (Leucippus)

- ^ Susanne Bobzien Determinism and Freedom in Stoic Philosophy (Oxford 1998) chapter 1.

- ^ Susanne Bobzien The Inadvertent Conception and Late Birth of the Free-Will Problem (Phronesis 43, 1998).

- ^ Michael Frede A Free Will: Origins of the Notion in Ancient Thought (Berkeley 2011).

- ^ Though Moses Maimonides was not arguing against the existence of God, but rather for the incompatibility between the full exercise by God of his omniscience and genuine human free will, his argument is considered by some as affected by Modal Fallacy. See, in particular, the article by Prof. Norman Swartz for Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Foreknowledge and Free Will and specifically Section 6: The Modal Fallacy

- ^ The Eight Chapters of Maimonides on Ethics (Semonah Perakhim), edited, annotated, and translated with an Introduction by Joseph I. Gorfinkle, pp. 99–100. (New York: AMS Press), 1966.

- ^ Swartz, Norman (2003) The Concept of Physical Law / Chapter 10: Free Will and Determinism ( https://www.sfu.ca/philosophy/physical-law/)

- ^ Lewis, E.R.; MacGregor, R.J. (2006). "On Indeterminism, Chaos, and Small Number Particle Systems in the Brain" (PDF). Journal of Integrative Neuroscience. 5 (2): 223–247. doi:10.1142/S0219635206001112.

- ^ Koch, Christof (September 2009). "Free Will, Physics, Biology and the Brain". In Murphy, Nancy; Ellis, George; O'Connor, Timothy. Downward Causation and the Neurobiology of Free Will. New York, USA: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-03204-2.

- ^ a b c Kenrick, D. T.; Li, N. P.; Butner, J. (2003). "Dynamical evolutionary psychology: Individual decision rules and emergent social norms" (PDF). Psychological Review. 110 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.3. PMID 12529056.

- ^ a b c Nowak A., Vallacher R.R., Tesser A., Borkowski W., (2000) "Society of Self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure", Psychological Review 107.

- ^ a b c Epstein J.M. and Axtell R. (1996) Growing Artificial Societies - Social Science from the Bottom. Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

- ^ a b c Epstein J.M. (1999) Agent Based Models and Generative Social Science. Complexity, IV (5)

- ^ John Conway's Game of Life

- ^ Karl Popper: Conjectures and refutations

- ^ Werndl, Charlotte (2009). "Are Deterministic Descriptions and Indeterministic Descriptions Observationally Equivalent?". Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 40 (3): 232–242. arXiv:1310.1615. Bibcode:2009SHPMP..40..232W. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2009.06.004.

- ^ Werndl, Charlotte (2009). Deterministic Versus Indeterministic Descriptions: Not That Different After All?. In: A. Hieke and H. Leitgeb (eds), Reduction, Abstraction, Analysis, Proceedings of the 31st International Ludwig Wittgenstein-Symposium. Ontos, 63-78.

- ^ J. Glimm, D. Sharp, Stochastic Differential Equations: Selected Applications in Continuum Physics, in: R.A. Carmona, B. Rozovskii (ed.) Stochastic Partial Differential Equations: Six Perspectives, American Mathematical Society (October 1998) (ISBN 0-8218-0806-0).

- ^ "Struggling with quantum logic: Q&A with Aaron O'Connell

- ^ Heisenberg, Werner (1949). Physikalische Prinzipien der Quantentheorie [Physical Principles of Quantum Theory]. Leipzig: Hirzel/University of Chicago Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780486601137.

- ^ a b Grand Design (2010), page 32: "the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets...so it seems that we are no more than biological machines and that free will is just an illusion", and page 72: "Quantum physics might seem to undermine the idea that nature is governed by laws, but that is not the case. Instead it leads us to accept a new form of determinism: Given the state of a system at some time, the laws of nature determine the probabilities of various futures and pasts rather than determining the future and past with certainty." (discussing a Many worlds interpretation)

- ^ Scientific American, "What is Quantum Mechanics Good For?"

- ^ Albert Einstein insisted that, "I am convinced God does not play dice" in a private letter to Max Born, 4 December 1926, Albert Einstein Archives Archived 19 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine reel 8, item 180

- ^ Jabs, Arthur (2016). "A conjecture concerning determinism, reduction, and measurement in quantum mechanics". Quantum Studies: Mathematics and Foundations. 3 (4): 279–292. arXiv:1204.0614. doi:10.1007/s40509-016-0077-7.

- ^ Bishop, Robert C. (2011). "Chaos, Indeterminism, and Free Will". In Kane, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Free Will (Second ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780195399691. OCLC 653483691.

The key question is whether to understand the nature of this probability as epistemic or ontic. Along epistemic lines, one possibility is that there is some additional factor (i.e., a hidden mechanism) such that once we discover and understand this factor, we would be able to predict the observed behavior of the quantum stoplight with certainty (physicists call this approach a "hidden variable theory"; see, e.g., Bell 1987, 1–13, 29–39; Bohm 1952a, 1952b; Bohm and Hiley 1993; Bub 1997, 40–114, Holland 1993; see also the preceding essay in this volume by Hodgson). Or perhaps there is an interaction with the broader environment (e.g., neighboring buildings, trees) that we have not taken into account in our observations that explains how these probabilities arise (physicists call this approach decoherence or consistent histories15). Under either of these approaches, we would interpret the observed indeterminism in the behavior of stoplights as an expression of our ignorance about the actual workings. Under an ignorance interpretation, indeterminism would not be a fundamental feature of quantum stoplights, but merely epistemic in nature due to our lack of knowledge about the system. Quantum stoplights would turn to be deterministic after all.

- ^ Baggott, Jim E. (2004). "Complementarity and Entanglement". Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy, and the Meaning of Quantum Theory. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-19-852536-2. OCLC 52486237.

So, was Einstein wrong? In the sense that the EPR paper argued in favour of an objective reality for each quantum particle in an entangled pair independent of the other and of the measuring device, the answer must be yes. But if we take a wider view and ask instead if Einstein was wrong to hold to the realist's belief that the physics of the universe should be objective and deterministic, we must acknowledge that we cannot answer such a question. It is in the nature of theoretical science that there can be no such thing as certainty. A theory is only 'true' for as long as the majority of the scientific community maintain a consensus view that the theory is the one best able to explain the observations. And the story of quantum theory is not over yet.

Bibliography[edit]

- Daniel Dennett (2003) Freedom Evolves. Viking Penguin.

- John Earman (2007) "Aspects of Determinism in Modern Physics" in Butterfield, J., and Earman, J., eds., Philosophy of Physics, Part B. North Holland: 1369-1434.

- George Ellis (2005) "Physics and the Real World", Physics Today.

- Epstein, J.M. (1999). "Agent Based Models and Generative Social Science". Complexity. IV (5): 5. Bibcode:1999Cmplx...4e..41E. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0526(199905/06)4:5<41::aid-cplx9>3.3.co;2-6.

- -------- and Axtell R. (1996) Growing Artificial Societies — Social Science from the Bottom. MIT Press.

- Kenrick, D. T.; Li, N. P.; Butner, J. (2003). "Dynamical evolutionary psychology: Individual decision rules and emergent social norms" (PDF). Psychological Review. 110 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.3. PMID 12529056.

- Albert Messiah, Quantum Mechanics, English translation by G. M. Temmer of Mécanique Quantique, 1966, John Wiley and Sons, vol. I, chapter IV, section III.

- Ernest Nagel (March 3, 1960). "Determinism in history". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, number 8. International Phenomenological Society. 20 (3): 291–317. doi:10.2307/2105051. JSTOR 2105051. (Online version found here)

- John T Roberts (2006). "Determinism". In Sahotra Sarkar; Jessica Pfeifer. The Philosophy of Science: A-M. Taylor & Francis. pp. 197 ff. ISBN 0415977096.

- Nowak A., Vallacher R.R., Tesser A., Borkowski W., (2000) "Society of Self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure", Psychological Review 107.

Further reading[edit]

- George Musser, "Is the Cosmos Random? (Einstein's assertion that God does not play dice with the universe has been misinterpreted)", Scientific American, vol. 313, no. 3 (September 2015), pp. 88–93.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Determinism |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Determinism. |

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Causal Determinism

- Determinism in History from the Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Philosopher Ted Honderich's Determinism web resource

- Determinism on Information Philosopher

- An Introduction to Free Will and Determinism by Paul Newall, aimed at beginners.

- The Society of Natural Science

- Determinism and Free Will in Judaism

- Snooker, Pool, and Determinism

.jpg/140px-Bled_(9664110474).jpg)