V. S. Ramachandran

V. S. Ramachandran | |

|---|---|

Ramachandran at the 2011 Time 100 gala | |

| Born | Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran 10 August 1951 |

| Residence | San Diego, California |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Research in neurology, visual perception, phantom limbs, synesthesia, autism, body integrity identity disorder |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | University of California, San Diego |

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran (born 10 August 1951) is a neuroscientist known primarily for his work in the fields of behavioral neurology and visual psychophysics. He is currently a Professor in the Department of Psychology and the Graduate Program in Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego. Ramachandran is the author of several books that have garnered widespread public interest. These include Phantoms in the Brain (1998), "A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness" (2004) and The Tell-Tale Brain (2010).

Ramachandran has achieved both professional and popular recognition. He has published papers on a wide variety of topics in neuroscience. His books, interviews, and lectures have helped build public interest in contemporary neuroscience. In 2011, Time listed him as one of "the most influential people in the world" on the "Time 100 list".[1]

Contents

Early life and education[edit]

Ramachandran (in accordance with some Tamil family name traditions, the town of his family's origin, Vilayanur, is placed first) was born in 1951 in Tamil Nadu, India.[2][3] His father, V. M. Subramanian, was an engineer who worked for the U.N. Industrial Development Organization and served as a diplomat in Bangkok, Thailand.[4][5] Ramachandran attended schools in Madras, and British schools in Bangkok.[6] Ramachandran obtained an M.B.B.S. from the University of Madras in Chennai, India,[7] and subsequently obtained a Ph.D. from Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. He then spent two years at Caltech, as a research fellow working with Jack Pettigrew. He was appointed Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego in 1983, and has been a full professor there since 1998.

Scientific career[edit]

Ramachandran's early research was on human visual perception using psychophysical methods to draw clear inferences about the brain mechanisms underlying visual processing. In the early 1990s Ramachandran began to focus on neurological syndromes such as phantom limbs, body integrity identity disorder and the Capgras delusion. He has also contributed to the understanding of synesthesia[5] and is known for inventing the mirror box.

Ramachandran is noted for his use of experimental methods that make relatively little use of complex technologies such as neuroimaging. Despite the apparent simplicity of his approach, he has generated many new ideas about the brain.[8] Ramachandran has encountered skepticism about some of his theories.[9][10] Ramachandran has responded that "I have—for better or worse—roamed the whole landscape of visual perception, stereopsis, phantom limbs, denial of paralysis, Capgras syndrome, synaesthesia, and many others."[11]

In addition to his academic research Ramachanran has served as a consultant in areas such as forensic psychology and the neuroscience of weight reduction. In 2007, Ramachandran served as an expert witness on pseudocyesis (false pregnancy) at the trial of Lisa M. Montgomery.[12] Ramachandran is currently serving as a consultant to a company (Modius) that is developing weight reduction technology that relies on electrically stimulating parts of the brain that control weight loss.[13]

Ramachandran is the director of a research group at the University of California, San Diego, known as the Center for Brain and Cognition.[14][15] This group, made up of students and researchers from different universities, is affiliated with the Department of Psychology at UCSD. Members of the CBC have published articles on a range of emerging theories related to neuroscience.[14] In 2012 Laura Case and Ramachancran published a theory about the possible role of brain plasticity in bigender alternation.[16] In 2017 Baland Jalal and Ramachandran published an article in which they speculated about the role of mirror neurons in the experience of the bedroom intruder during sleep paralysis.[17]

Theories and research[edit]

Phantom limbs[edit]

When an arm or leg is amputated, patients often continue to feel vividly the presence of the missing limb as a "phantom limb" (an average of 80%). Building on earlier work by Ronald Melzack (McGill University) and Timothy Pons (NIMH), Ramachandran theorized that there was a link between the phenomenon of phantom limbs and neural plasticity in the adult human brain. In 1993, working with T.T. Yang who was conducting MEG research at the Scripps Research Institute,[18] Ramachandran demonstrated that there had been measurable changes in the somatosensory cortex of a patient who had undergone an arm amputation.[19][20] Ramachandran theorized that there was a relationship between the cortical reorganization evident in the MEG image and the referred sensations he had observed in other subjects.[21] (In 1996 Knecht et al. published an analysis of Ramachandran's hypothesis that concluded that there was no topographic relationship between referred sensations and cortical reorganization in the primary cortical areas.[22]) Neuroscientists continue to investigate the question of which neural processes are related to phantom limb phenomena.[23]

Mirror visual feedback / Mirror Therapy[edit]

Ramachandran is credited with the invention of the mirror box and the introduction of mirror visual feedback (mirror therapy) as a treatment for phantom limb paralysis. Ramachandran found that in some cases restoring movement to a paralyzed phantom limb reduced pain as well.[24]

Systematic reviews of the research literature on mirror therapy (MT) have arrived at conflicting conclusions about the effectiveness of MT. A 2014 review found that MT can exert a strong influence on the motor network, mainly through increased cognitive penetration in action control.[25] However, a 2016 review concluded that the level of evidence is insufficient to recommend MT as a first intention treatment for phantom limb pain.[26]

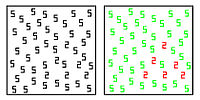

Neural basis of synesthesia[edit]

Ramachandran was one of the first scientists to theorize that grapheme-color synesthesia arises from a cross-activation between brain regions.[27][28] Ramachandran and his graduate student, Ed Hubbard, conducted research with functional magnetic resonance imaging that found increased activity in the color recognition areas of the brain in synesthetes compared to non-synesthetes.[28][29] Ramachandran has speculated that conceptual metaphors may also have a neurological basis in cortical cross-activation. As of 2015, the neurological basis of synesthesia had not been established.[30]

Mirror neurons[edit]

Ramachandran's theories about the role of mirror neurons have attracted a great deal of discussion and debate.[31][32] (Mirror neurons were first reported in a paper published in 1992 by a team of researchers led by Giacomo Rizzolatti at the University of Parma.)[33] Ramachandran has speculated that research into the role of mirror neurons will help explain a variety of human mental capacities such as empathy, imitation learning, and the evolution of language. In 2000, Ramachandran made a prediction that "mirror neurons will do for psychology what DNA did for biology: they will provide a unifying framework and help explain a host of mental abilities that have hitherto remained mysterious and inaccessible to experiments."[34][35] However, over the past ten years, many of the exciting theories about mirror neurons have not held up under scrutiny.[36]

"Broken Mirrors" theory of autism[edit]

In 1999, Ramachandran, in collaboration with then post-doctoral fellow Eric Altschuler and colleague Jaime Pineda, hypothesized that a loss of mirror neurons might be the key deficit that explains many of the symptoms and signs of autism spectrum disorders.[37] Between 2000 and 2006 Ramachandran and his colleagues at UC San Diego published a number of articles in support of this theory, which became known as the "Broken Mirrors" theory of autism.[38][39][40] Ramachandran and his colleagues did not measure mirror neuron activity directly; rather they demonstrated that children with ASD showed abnormal EEG responses (known as Mu wave suppression) when they observed the activities of other people. Ramachandran's "broken mirrors hypothesis" explanation for autism remains controversial.[32][41][42]

Xenomelia (Apotemnophilia)[edit]

In 2008, Ramachandran, along with David Brang and Paul McGeoch, published the first paper to theorize that apotemnophilia is a neurological disorder caused by damage to the right parietal lobe of the brain.[43] This rare disorder, in which a person desires the amputation of a limb, was first identified by John Money in 1977. Building on medical case studies that linked brain damage to syndromes such as somatoparaphrenia (lack of limb ownership) the authors speculated that the desire for amputation could be related to changes in the right parietal lobe. In 2011 McGeoch, Brang and Ramachandran reported a functional imaging experiment involving four subjects who desired lower limb amputations. MEG scans demonstrated that their right superior parietal lobules were significantly less active in response to tactile stimulation of a limb that the subjects wished to have amputated, as compared to age/sex matched controls. [44] The authors introduced the word "Xenomelia" to describe this syndrome, which is derived from the Greek for "foreign" and "limb".

As of 2014, there was no medical consensus as to the cause of this condition.[45]

Awards and honors[edit]

Ramachandran was elected to a visiting fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford (1998–1999). In addition, he was a Hilgard visiting professor at Stanford University in 2005. He has received honorary doctorates from Connecticut College (2001) and the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (2004).[46] Ramachandran received the annual Ramon y Cajal award (2004) from the International Neuropsychiatric Society,[47] and the Ariëns Kappers Medal from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences for his contributions to Neuroscience (1999). In 2005 Ramachandran received the Henry Dale Medal from the Royal institution for "outstanding research of an interdisciplinary nature".[48] In 2007, the President of India conferred on him the third highest civilian award and honorific title in India, the Padma Bhushan.[49] In 2014, Ramachandran was appointed an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Books written[edit]

- Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind, coauthor Sandra Blakeslee, 1998 (ISBN 0-688-17217-2).

- Encyclopedia of the Human Brain (editor-in-chief), three volumes, 2002 (ISBN 0-12-227210-2).

- The Emerging Mind, 2003 (ISBN 1-86197-303-9).

- A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness: From Impostor Poodles to Purple Numbers, 2005 (ISBN 0-13-187278-8; paperback edition).

- The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human, 2010 (ISBN 978-0-393-07782-7).

- The Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (editor-in-chief), four-volume second edition, 2012 (ISBN 978-0123750006).

See also[edit]

- Body image

- Lisa M. Montgomery

- Mirror neuron

- Oliver Sacks

- Sound symbolism (phonaesthesia)

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

References[edit]

- ^ Insel, Thomas (2011-04-21). "The 2011 TIME 100 - TIME". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- ^ Andrew Anthony (30 January 2011). "VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Colapinto, John (4 May 2009). "Brain Games" – via www.newyorker.com.

- ^ "The Science Studio Interview, June 10, 2006, transcript" (PDF).

- ^ a b Colapinto, J (11 May 2009). "Brain Games; The Marco Polo of Neuroscience". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Ramachandran V.S., The Making of a Scientist, essay included in Curious Minds:How a Child Becomes a Scientist, page 211 [1]

- ^ Caltech Catalog,1987-1988, page 325

- ^ Anthony, VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience, The Observer, 29 January 2011.

- ^ Brugger, Peter, Book Review, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, Vol. 17, Issue 4, 2012

- ^ Adler,Tessa,Unsolved Mysteries: Phantom Limbs,Yale Scientific,July 1, 2014 22:29[2]

- ^ Ramachandran,V.S. Author Response, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, Vol. 17, Issue 4, 2012

- ^ AP,NBC website,Crime and Courts,10/17/2007[3]

- ^ Auerbach,Brad,Modius Intends To Buck The Trend Of Weight Loss Solutions With Data-Based Success And FDA Approval,Forbes,Mar 16, 2018,[4]

- ^ a b "The Center for Brain and Cognition - Research". cbc.ucsd.edu.

- ^ "V.S. Ramachandran: The 'House' of Neuro-Science - Video". TIME.com.

- ^ Case,Ramachandran,Alternating gender incongruity: A new neuropsychiatric syndrome providing insight into the dynamic plasticity of brain-sex, May 2012 Volume78,Issue5,Pages 626–631

- ^ Jalal,Ramachandran,Sleep Paralysis, "The Ghostly Bedroom Intruder" and Out-of-Body Experiences: The Role of Mirror Neurons,Front. Hum. Neurosci., 28 February 2017 [5]

- ^ Yang, UCSD Faculty web page Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yang, T. T; Gallen, C. C; Ramachandran, V. S; Cobb, S; Schwartz, B. J; Bloom, F. E (1994). "Noninvasive detection of cerebral plasticity in adult human somatosensory cortex". NeuroReport. 5 (6): 701–4. doi:10.1097/00001756-199402000-00010. PMID 8199341.

- ^ Flor, Herta; Nikolajsen, Lone; Staehelin Jensen, Troels (2006). "Phantom limb pain: A case of maladaptive CNS plasticity?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 7 (11): 873–81. doi:10.1038/nrn1991. PMID 17053811.

- ^ Ramachandran, V; Rogers-Ramachandran, D; Stewart, M; Pons, Tim P (1992). "Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization". Science. 258 (5085): 1159–60. Bibcode:1992Sci...258.1159R. doi:10.1126/science.1439826. PMID 1439826.

- ^ Knecht, S, Henningsen, H, Elbert, T, Flor, H, Hohling, C, Pantev, C, Taub, E, Reorganizational and perceptional changes after amputation, Brain,1996,119,1213-1219 [6]

- ^ Andoh, J; Diers, M; Milde, C; Frobel, C; Kleinböhl, D; Flor, H (2017). "Neural correlates of evoked phantom limb sensations". Biological Psychology. 126: 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.04.009. PMC 5437955. PMID 28445695.

- ^ Ramachandran, V. S; Rogers-Ramachandran, D (1996). "Synaesthesia in Phantom Limbs Induced with Mirrors". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 263 (1369): 377–86. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0058. PMID 8637922.

- ^ Deconinck,Smorenburg,Benham,Ledebt,Feltham,Savelsbergh,Reflections on mirror therapy: a systematic review of the effect of mirror visual feedback on the brain,Neurorehabil Neural Repair,2015,May29(4),349-61[7]

- ^ Barbin,Seethaa,Casillasc,Paysantd,Pérennou,Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine,Volume 59, Issue 4, September 2016,Pages270-275

- ^ Ramachandran VS & Hubbard EM (2001). "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 8 (12): 3–34.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Edward M; Arman, A. Cyrus; Ramachandran, Vilayanur S; Boynton, Geoffrey M (2005). "Individual Differences among Grapheme-Color Synesthetes: Brain-Behavior Correlations". Neuron. 45 (6): 975–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.008. PMID 15797557.

- ^ Hubbard, Edward M; Ramachandran, V.S (2005). "Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Synesthesia". Neuron. 48 (3): 509–20. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. PMID 16269367.

- ^ Hupel,Jean-Michel,Dojat,Michel,A critical review of the neuroimaging literature on synesthesia,Frontiers In Human Neuroscience,2015,9,103,Published online 2015 Mar 3 [8]

- ^ Jarrett,Christian, A Calm Look At The Most Hyped Concept in Neuroscience -- Mirror Neurons,Wired,Science, 12,13,2013[9]

- ^ a b Costandi,Mo,Reflecting on mirror neurons,Neurophilosophy,The Guardian,23 August 2013[10]

- ^ Rizzolatti, Giacomo; Fabbri-Destro, Maddalena (2009). "Mirror neurons: From discovery to autism". Experimental Brain Research. 200 (3–4): 223–37. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-2002-3. PMID 19760408.

- ^ Jarrett, Christian (10 December 2012). "Mirror Neurons: The Most Hyped Concept in Neuroscience?". Psychology Today.

- ^ Baron-Cohen, Making Sense of the Brain's Mysteries, American Scientist, On-line Book Review, July–August, 2011 [11]

- ^ Taylor,John,Mirror Neurons After a Quarter Century: New light, new cracks,Science In The News (web article)Harvard University,Aug 29,2016[12]

- ^ E.L. Altschuler, A. Vankov, E.M. Hubbard, E. Roberts, V.S. Ramachandran and J.A. Pineda (2000). "Mu wave blocking by observer of movement and its possible use as a tool to study theory of other minds". 30th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Oberman, Lindsay M; Hubbard, Edward M; McCleery, Joseph P; Altschuler, Eric L; Ramachandran, Vilayanur S; Pineda, Jaime A (2005). "EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders". Cognitive Brain Research. 24 (2): 190–8. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.014. PMID 15993757.

- ^ Ramachandran, Vilayanur S; Oberman, Lindsay M (2006). "Broken Mirrors: A Theory of Autism". Scientific American. 295 (5): 62–9. Bibcode:2006SciAm.295e..62R. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1106-62. PMID 17076085.

- ^ Oberman, Lindsay M; Ramachandran, Vilayanur S (2007). "The simulating social mind: The role of the mirror neuron system and simulation in the social and communicative deficits of autism spectrum disorders". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (2): 310–27. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.310. PMID 17338602.

- ^ Christian Jarrett,A Calm Look at the Most Hyped Concept in Neuroscience - Mirror Neurons,Wired,13 December 2013,[13]

- ^ Fan,Y.T.;Decety,J.;Yang,C.Y.;Liu,J.L.; Cheng,Y, "Unbroken mirror neurons in autism spectrum disorders",Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,26 May 2010 [14]

- ^ Brang, David; McGeoch, Paul D; Ramachandran, Vilayanur S (2008). "Apotemnophilia: A neurological disorder". NeuroReport. 19 (13): 1305–6. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830abc4d. PMID 18695512.

- ^ McGeoch, P. D; Brang, D; Song, T; Lee, R. R; Huang, M; Ramachandran, V. S (2011). "Xenomelia: A new right parietal lobe syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 82 (12): 1314–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2011-300224. PMID 21693632.

- ^ Sedda,Anna,Bottini,Gabriella, Apotemnophilia, body integrity identity disorder or xenomelia? Psychiatric and neurologic etiologies face each other,Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2014;10: 1255–1265.[15]

- ^ Oberman, Lindsay M; McCleery, Joseph P; Ramachandran, Vilayanur S; Pineda, Jaime A (2007). "EEG evidence for mirror neuron activity during the observation of human and robot actions: Toward an analysis of the human qualities of interactive robots". Neurocomputing. 70 (13–15): 2194–203. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2006.02.024.

- ^ "International Neuropsychiatric Associatio". International Neuropsychiatric Associatio.

- ^ http://cbc.ucsd.edu/ramabio.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Search on "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) for Ramachandaran (sic!) in March 2008.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vilayanur S. Ramachandran |

- 1951 births

- 20th-century Indian medical doctors

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- American academics of Indian descent

- American agnostics

- American male scientists of Indian descent

- American people of Tamil descent

- Autism researchers

- Cognitive neuroscientists

- Columbia University staff

- Fellows of the Society of Experimental Psychologists

- Harvard University staff

- Indian agnostics

- Indian emigrants to the United States

- Indian neuroscientists

- Living people

- Neurotheology

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering

- Medical doctors from Tamil Nadu

- Stanford University Department of Psychology faculty

- University of California, San Diego faculty

- University of Madras alumni