Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

| ICD-9-CM | 94.01 |

| MeSH | D014888 |

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) is an IQ test designed to measure intelligence and cognitive ability in adults and older adolescents.[1] The original WAIS (Form I) was published in February 1955 by David Wechsler, as a revision of the Wechsler–Bellevue Intelligence Scale, released in 1939.[2] It is currently in its fourth edition (WAIS-IV) released in 2008 by Pearson, and is the most widely used IQ test, for both adults and older adolescents, in the world. Data collection for the next version (WAIS 5) began in 2016 and is projected to be complete in 2019.

Contents

History[edit]

The WAIS is founded on Wechsler's definition of intelligence, which he defined as "... the global capacity of a person to act purposefully, to think rationally, and to deal effectively with his environment."[3] He believed that intelligence was made up of specific elements that could be isolated, defined, and subsequently measured. However, these individual elements were not entirely independent, but were all interrelated. His argument, in other words, is that general intelligence is composed of various specific and interrelated functions or elements that can be individually measured.[4]

This theory differed greatly from the Binet scale which, in Wechsler's day, was generally considered the supreme authority with regard to intelligence testing. A drastically revised new version of the Binet scale, released in 1937, received a great deal of criticism from David Wechsler (after whom the original Wechsler–Bellevue Intelligence scale and the modern Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV are named).[4]

- Wechsler was a very influential advocate for the concept of non-intellective factors, and he felt that the 1937 Binet scale did not do a good job of incorporating these factors into the scale (non-intellective factors are variables that contribute to the overall score in intelligence, but are not made up of intelligence-related items. These include things such as lack of confidence, fear of failure, attitudes, etc.).

- Wechsler did not agree with the idea of a single score that the Binet test gave.[4]

- Wechsler argued that the Binet scale items were not valid for adult test-takers because the items were chosen specifically for use with children.[4]

- The "Binet scale's emphasis on speed, with timed tasks scattered throughout the scale, tended to unduly handicap older adults."[4]

- Wechsler believed that "mental age norms clearly did not apply to adults."[4]

- Wechsler criticized the then existing Binet scale because "it did not consider that intellectual performance could deteriorate as a person grew older."[4]

These criticisms of the 1937 Binet test helped produce the Wechsler–Bellevue scale, released in 1939. While this scale has been revised (resulting in the present day WAIS-IV), many of the original concepts Wechsler argued for, have become standards in psychological testing, including the point-scale concept and the performance-scale concept.[4]

Wechsler–Bellevue Intelligence Scale[edit]

The Wechsler–Bellevue tests were innovative in the 1930s because they:

- gathered tasks created for nonclinical purposes for administration as a "clinical test battery",[5]

- used the point scale concept instead of the age scale, and

- included a non-verbal performance scale.[6][7]

Point scale concept[edit]

In the Binet scales (prior to the 1986 version) items were grouped according to age level. Each of these age levels was composed of a group of tasks that could be passed by two-thirds to three-quarters of the individuals in that level. This meant that items were not arranged according to content. Additionally, an individual taking a Binet test would only receive credit if a certain number of the tasks were completed. This meant that falling short just one task required for the credit, resulted in no credit at all (for example, if passing three out of four tasks was required to receive credit, then passing two yielded no credit).[4]

The point scale concept significantly changed the way testing was done by assigning credits or points to each item. This had two large effects. First, this allowed items to be grouped according to content. Second, participants were able to receive a set number of points or credits for each item passed.[8] The result was a test that could be made up of different content areas (or subtests) with both an overall score and a score for each content area. In turn, this allowed for an analysis to be made of an individual's ability in a variety of content areas (as opposed to one general score).[4]

The Non-Verbal Performance Scale[edit]

The non-verbal performance scale was also a critical difference from the Binet scale. Since the "early Binet scale had been persistently and consistently criticized for its emphasis on language and verbal skills,"[4] Wechsler made an entire scale that allowed the measurement of nonverbal intelligence. This became known as a performance scale. Essentially, this scale required a subject to do something (such as "copying symbols or point to a missing detail"[4]) rather than just answer questions. This was an important development as it attempted to overcome biases that were caused by "language, culture, and education."[4] Further, this scale also provided an opportunity to observe a different type of behavior because something physical was required. Clinicians were able to observe how a participant reacted to the "longer interval of sustained effort, concentration, and attention" that the performance tasks required.[4]

While the Wechsler–Bellevue scale was the first to effectively use the performance scale (meaning that (1) there was a "possibility of directly comparing an individual's verbal and nonverbal intelligence",[4] and (2) that "the results of both scales were expressed in comparable units"[4]), the idea had been around for a while. The Binet scale did have performance tasks (although they were geared towards children) and there were entire tests that were considered supplements or alternatives (an example of such a performance test is the Leiter International Performance Scale).[4]

WAIS[edit]

This section needs expansion with: WAIS vs. WAIS-R above. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

The WAIS was initially created as a revision of the Wechsler–Bellevue Intelligence Scale (WBIS), which was a battery of tests published by Wechsler in 1939. The WBIS was composed of subtests that could be found in various other intelligence tests of the time, such as Robert Yerkes' army testing program and the Binet-Simon scale. The WAIS was first released in February 1955 by David Wechsler. Because the Wechsler tests included non-verbal items (known as performance scales) as well as verbal items for all test-takers, and because the 1960 form of Lewis Terman's Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales was less carefully developed than previous versions, Form I of the WAIS surpassed the Stanford–Binet tests in popularity by the 1960s.[2]

WAIS-R[edit]

The WAIS-R, a revised form of the WAIS, was released in 1981 and consisted of six verbal and five performance subtests. The verbal tests were: Information, Comprehension, Arithmetic, Digit Span, Similarities, and Vocabulary. The Performance subtests were: Picture Arrangement, Picture Completion, Block Design, Object Assembly, and Digit Symbol. A verbal IQ, performance IQ and full scale IQ were obtained.[9]

This revised edition did not provide new validity data, but used the data from the original WAIS; however new norms were provided, carefully stratified.[9]

WAIS-III[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

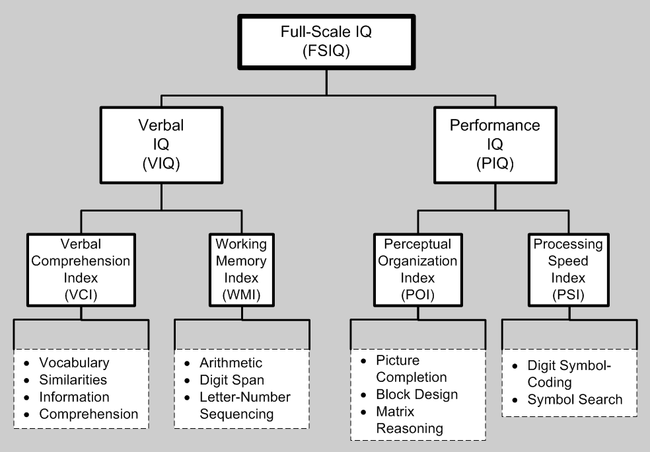

The WAIS-III, a subsequent revision of the WAIS and the WAIS-R, was released in 1997. It provided scores for Verbal IQ, Performance IQ, and Full Scale IQ, along with four secondary indices (Verbal Comprehension, Working Memory, Perceptual Organization, and Processing Speed).

Verbal IQ (VIQ)[edit]

Included seven tests and provided two subindexes; verbal comprehension and working memory.

The Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) included the following tests:

- Information

- Similarities

- Vocabulary

The Working Memory Index (WMI) included:

- Arithmetic

- Digit Span

Letter-Number Sequencing and Comprehension are not included in these indices, but are used as substitutions for spoiled subtests within the WMI and VCI, respectively.

Performance IQ (PIQ)[edit]

Included six tests and it also provided two subindexes; perceptual organization and processing speed.

The Perceptual Organization Index (POI) included:

- Block Design

- Matrix Reasoning

- Picture Completion

The Processing Speed Index (PSI) included:

- Digit Symbol-Coding

- Symbol Search

Two tests; Picture Arrangement and Object Assembly were not included in the indexes. Object Assembly is not included in the PIQ.

WAIS-IV[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The current version of the test, the WAIS-IV, which was released in 2008, is composed of 10 core subtests and five supplemental subtests, with the 10 core subtests comprising the Full Scale IQ. With the new WAIS-IV, the verbal/performance subscales from previous versions were removed and replaced by the index scores. The General Ability Index (GAI) was included, which consists of the Similarities, Vocabulary and Information subtests from the Verbal Comprehension Index and the Block Design, Matrix Reasoning and Visual Puzzles subtests from the Perceptual Reasoning Index. The GAI is clinically useful because it can be used as a measure of cognitive abilities that are less vulnerable to impairments of processing and working memory.

Index scores and scales[edit]

There are four index scores representing major components of intelligence:

- Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI)

- Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI)

- Working Memory Index (WMI)

- Processing Speed Index (PSI)

Two broad scores, which can be used to summarize general intellectual abilities, can also be derived:

- Full Scale IQ (FSIQ), based on the total combined performance of the VCI, PRI, WMI, and PSI

- General Ability Index (GAI), based only on the six subtests that the VCI and PRI comprise.

| Index | Task | Core? | Description | Proposed abilities measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Comprehension | Similarities | Participants are given two words or concepts and have to describe how they are similar. | Abstract verbal reasoning; semantic knowledge | |

| Vocabulary | Participants must name objects in pictures or define words presented to them. | Semantic knowledge; verbal comprehension and expression | ||

| Information | Participants are questioned about their general knowledge. | Degree of general information acquired from culture | ||

| Comprehension | Ability to express abstract social conventions, rules and expressions | |||

| Perceptual Reasoning | Block Design | Visual spatial processing and problem solving; visual motor construction | ||

| Matrix Reasoning | Nonverbal abstract problem solving, inductive reasoning | |||

| Visual Puzzles | Visual spatial reasoning | |||

| Picture Completion | Ability to quickly perceive visual details | |||

| Figure Weights | Quantitative reasoning | |||

| Working Memory | Digit Span | Participants must recall a series of numbers in order. | Working memory, attention, encoding, auditory processing | |

| Arithmetic | Quantitative reasoning, concentration, mental manipulation | |||

| Letter-Number Sequencing | Participants must recall a series of numbers in increasing order and letters in alphabetical order. | Working memory, attention, mental control | ||

| Processing Speed | Symbol Search | Processing speed | ||

| Coding | Processing speed, associative memory, graphomotor speed | |||

| Cancellation | Processing speed |

Standardization[edit]

The WAIS-IV was standardized on a sample of 2,200 people in the United States ranging in age from 16 to 90.[10] An extension of the standardization has been conducted with 688 Canadians in the same age range.

Age range and uses[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The WAIS-IV measure is appropriate for use with individuals aged 16–90 years. For individuals under 16 years, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC, 6–16 years) and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI, 2½–7 years, 7 months) are used.

Intelligence tests may be utilized in populations with psychiatric illness or brain injury, in order to assess level of cognitive functioning, though some regard this use as controversial[who?]. Rehabilitation psychologists and neuropsychologists use the WAIS-IV and other neuropsychological tests to assess how the brain is functioning after injury. Specific subtests provide information on a specific cognitive function. For example, digit span may be used to get a sense of attentional difficulties. Others employ the WAIS-R NI (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised as a Neuropsychological Instrument), another measure published by Harcourt. Each subtest score is tallied and calculated with respect to neurotypical or brain-injury norms. As the WAIS is developed for the average, non-injured individual, separate norms were developed for appropriate comparison among similar functioning individuals.

WASI[edit]

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) is a very short form of estimating intellectual functioning.[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Kaufman, Alan S.; Lichtenberger, Elizabeth (2006). Assessing Adolescent and Adult Intelligence (3rd ed.). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-471-73553-3. Lay summary (22 August 2010).

- ^ a b Kaufman, Alan S.; Lichtenberger, Elizabeth (2006). Assessing Adolescent and Adult Intelligence (3rd ed.). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-471-73553-3. Lay summary (22 August 2010).

- ^ Wechsler, David (1939). The Measurement of Adult Intelligence. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Witkins. p. 229.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kaplan, R. M.; Saccuzzo, D. P. (2010). Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, & Issues (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage learning.

- ^ Kaufman, Alan S.; Lichtenberger, Elizabeth (2006). Assessing Adolescent and Adult Intelligence (3rd ed.). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-471-73553-3. Lay summary (22 August 2010).

- ^ Nicolas, S., Andrieu, B., Croizet, J.-C., Sanitioso, R. B., & Burman, J. T. (2013). Sick? Or slow? On the origins of intelligence as a psychological object. Intelligence, 41(5), 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.08.006 (This is an open access article, made freely available by Elsevier.)

- ^ Kaufman, Alan S. (2009). IQ Testing 101. New York: Springer Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8261-0629-2. Sattler, Jerome M. (2008). Assessment of Children: Cognitive Foundations. La Mesa (CA): Jerome M. Sattler, Publisher. inside back cover. ISBN 978-0-9702671-4-6. Lay summary (28 July 2010).

- ^ Kaplan, R. M.; Saccuzzo, D. P. (2009). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ^ a b "Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale--Revised". LIST OF TESTS Available from the CPS Testing Library. Center for Psychological Studies at Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ "Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition Now Available From Pearson" (Press release). Pearson. 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ Validity of the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence and other very short forms of estimating intellectual functioning. by BN Axelrod - 2002 - Cited by 187 Performance on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) was compared to performance on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI), .

Further reading[edit]

- Matarazzo, Joseph D. (1972). Wechsler's Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence (5th and enlarged ed.). Baltimore (MD): Williams & Witkins. Lay summary (PDF) (4 June 2013).

- Wechsler, David (1939). The Measurement of Adult Intelligence. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Witkins.

- Wechsler, David (1958). The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence (4th ed.). Baltimore (MD): Williams & Witkins. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Weiss, Lawrence G.; Saklofske, Donald H.; Coalson, Diane; Raiford, Susan, eds. (2010). WAIS-IV Clinical Use and Interpretation: Scientist-Practitioner Perspectives. Practical Resources for the Mental Health Professional. Alan S. Kaufman (Foreword). Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-375035-8. Lay summary (16 August 2010). This practitioner's handbook includes chapters by Diane L. Coalson, Susan Engi Raiford, Donald H. Saklofske, Lawrence G. Weiss, Hsinyi Chen, Jossette G. Harris, James A. Holdnack, Xiaobin Zhou, Jianjun Zhu, Jacques Gregoire, Munro Cullum, Glenn Larrabee, Gerald Goldstein, Timothy A. Salthouse, and Lisa W. Drozdick.

External links[edit]

- FAQ/Finding Information About Psychological Tests (American Psychological Association)

- Classics in the History of Psychology