Science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction, typically dealing with imaginative concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, and extraterrestrial life. Science fiction often explores the potential consequences of scientific and other innovations, and has been called a "literature of ideas".[1][2]

Contents

Definitions[edit]

"Science fiction" is difficult to define, as it includes a wide range of subgenres and themes. James Blish wrote: "Wells used the term originally to cover what we would today call ‘hard’ science fiction, in which a conscientious attempt to be faithful to already known facts (as of the date of writing) was the substrate on which the story was to be built, and if the story was also to contain a miracle, it ought at least not to contain a whole arsenal of them."[3]

Isaac Asimov said: "Science fiction can be defined as that branch of literature which deals with the reaction of human beings to changes in science and technology."[4] According to Robert A. Heinlein, "a handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method."[5]

Lester del Rey wrote, "Even the devoted aficionado or fan—has a hard time trying to explain what science fiction is", and that the reason for there not being a "full satisfactory definition" is that "there are no easily delineated limits to science fiction."[6] Author and editor Damon Knight summed up the difficulty, saying "science fiction is what we point to when we say it",[7] while author Mark C. Glassy argues that the definition of science fiction is like the definition of pornography: you do not know what it is, but you know it when you see it.[8]

Alternative terms[edit]

Forrest J Ackerman is credited with first using the term "Sci-Fi" (analogous to the then-trendy "hi-fi") in 1954.[9] As science fiction entered popular culture, writers and fans active in the field came to associate the term with low-budget, low-tech "B-movies" and with low-quality pulp science fiction.[10][11][12] By the 1970s, critics within the field such as Knight and Terry Carr were using sci-fi to distinguish hack-work from serious science fiction.[13] Peter Nicholls writes that "SF" (or "sf") is "the preferred abbreviation within the community of sf writers and readers".[14] Robert Heinlein found even "science fiction" insufficient and suggested the term speculative fiction to be used instead, which has continued to be applied to "serious" or "thoughtful" science fiction.

History[edit]

Science fiction had its beginnings in the time when the line between myth and fact was blurred. Written in the 2nd century AD by the Hellenized Syrian satirist Lucian, A True Story contains many themes and tropes that are characteristic of modern science fiction, including travel to other worlds, extraterrestrial lifeforms, interplanetary warfare, and artificial life. Some consider it the first science fiction novel.[15] Some of the stories from The Arabian Nights,[16][17] along with the 10th century The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter[17] and Ibn al-Nafis's 13th century Theologus Autodidactus[18] also contain elements of science fiction.

Products of the Age of Reason and the development of modern science itself, Johannes Kepler's Somnium (1634), Francis Bacon's The New Atlantis (1627),[19] Cyrano de Bergerac's Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657) and The States and Empires of the Sun (1662), Margaret Cavendish's "The Blazing World" (1666),[20] Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), Ludvig Holberg's novel Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum (1741) and Voltaire's Micromégas (1752) are some of the first true science fantasy works.[21][22] Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan considered Somnium the first science fiction story. It depicts a journey to the Moon and how the Earth's motion is seen from there.[23]

Following the 18th-century development of the novel as a literary form, Mary Shelley's books Frankenstein (1818) and The Last Man (1826) helped define the form of the science fiction novel. Brian Aldiss has argued that Frankenstein was the first work of science fiction.[24] Edgar Allan Poe wrote several stories considered science fiction, including one about a trip to the Moon.[25][26] Jules Verne was noted for his attention to detail and scientific accuracy, especially Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) which predicted the modern nuclear submarine.[27][28][29][30] In 1887 the novel El anacronópete by Spanish author Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau introduced the first time machine.[31][32]

Many critics consider H. G. Wells one of science fiction's most important authors,[33][34] or even "the Shakespeare of science fiction".[35] His notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). His science fiction imagined alien invasion, biological engineering, invisibility, and time travel. In his non-fiction futurologist works he predicted the advent of airplanes, military tanks, nuclear weapons, satellite television, space travel, and something resembling the World Wide Web.[36]

In 1912 Edgar Rice Burroughs published A Princess of Mars, the first of his three-decade-long planetary romance series of Barsoom novels, set on Mars and featuring John Carter as the hero.[37]

In 1926 Hugo Gernsback published the first American science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, in which he wrote:

By 'scientifiction' I mean the Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision... Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading—they are always instructive. They supply knowledge... in a very palatable form... New adventures pictured for us in the scientifiction of today are not at all impossible of realization tomorrow... Many great science stories destined to be of historical interest are still to be written... Posterity will point to them as having blazed a new trail, not only in literature and fiction, but progress as well.[38][39][40]

In 1928 E. E. "Doc" Smith’s first published work, The Skylark of Space written in collaboration with Lee Hawkins Garby, appeared in Amazing Stories. It is often called the first great space opera.[41] In 1928 Philip Francis Nowlan's original Buck Rogers story, Armageddon 2419, appeared in Amazing Stories. This was followed by a Buck Rogers comic strip, the first serious science fiction comic.[42]

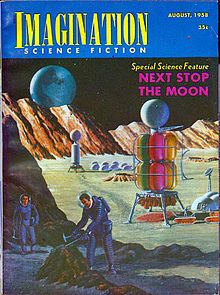

In 1937 John W. Campbell became editor of Astounding Science Fiction, an event which is sometimes considered the beginning of the Golden Age of Science Fiction characterized by stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress.[43] In 1942, Isaac Asimov started his Foundation series, which chronicles the rise and fall of galactic empires and introduced psychohistory.[44][45] The "Golden Age" is often said to have ended in 1946, but sometimes the late 1940s and the 1950s are included.[46]

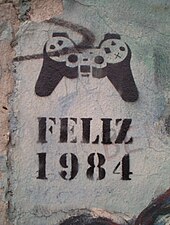

In 1949 George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four was an important example of dystopian science fiction.[47][48] Theodore Sturgeon’s 1953 novel More Than Human explored possible future human evolution.[49][50][51] In 1957 Andromeda: A Space-Age Tale by the Russian writer and paleontologist Ivan Yefremov presented a view of a future interstellar communist civilization and is considered one of the most important Soviet science fiction novels.[52][53] In 1959 Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers marked a departure from his earlier juvenile stories and novels.[54] It is one of the first and most influential examples of military science fiction,[55][56] and introduced the concept of powered armor exoskeletons.[57][58][59] The German space opera series Perry Rhodan, by various authors, started in 1961 with an account of the first Moon landing and has since expanded to the entire Universe and billions of years; becoming the most popular science fiction book series of all time.[60]

In the 1960s and 1970s New Wave science fiction was known for its embrace of a high degree of experimentation, both in form and in content, and a highbrow and self-consciously "literary" or artistic sensibility.[21][61][62] In 1961 Solaris by Stanisław Lem was published in Poland.[63] The novel dealt with the theme of human limitations as its characters attempted to study a seemingly intelligent ocean on a newly discovered planet.[64][65] 1965's Dune by Frank Herbert featured a much more complex and detailed imagined future society than had been common in science fiction before.[66] In 1968 Philip K. Dick’s best-known novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was published. It is the literary source of the film Blade Runner.[67] 1969's The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin was set on a planet in which the inhabitants have no fixed gender. It is one of the most influential examples of social science fiction, feminist science fiction, and anthropological science fiction.[68][69][70]

In 1976 C. J. Cherryh published Gate of Ivrel and Brothers of Earth, which began her Alliance-Union universe future history series.[71][72][73] In 1979 Science Fiction World began publication in the People's Republic of China.[74] It dominates the Chinese science fiction magazine market, at one time claiming a circulation of 300,000 copies per issue, with an estimate of 3–5 readers per copy (giving it a total readership of at least 1 million) making it the world's most popular science fiction periodical.[75]

In 1984 William Gibson’s first novel Neuromancer helped popularize cyberpunk, and the word "cyberspace" – a term he coined in his 1982 short story Burning Chrome.[76][77][78] In 1986 Shards of Honor by Lois McMaster Bujold began her Vorkosigan Saga.[79][80] 1992's Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson predicted immense social upheaval due to the information revolution.[81] In 2007 Liu Cixin's novel, The Three-Body Problem, was published in China. It was translated into English by Ken Liu and published by Tor Books in 2014, and won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel.[82] Liu was the first Asian writer to win "Best Novel."[83]

Emerging themes in late Twentieth and early Twenty-first century science fiction include environmental issues, the implications of the global Internet and the expanding information universe, questions about biotechnology and nanotechnology, as well as a post-Cold War interest in post-scarcity societies. Recent trends and sub-genres include steampunk,[84] biopunk,[85][86] and mundane science fiction.[87][88]

Film[edit]

The first known science fiction film is 1902's A Trip to the Moon, directed by French filmmaker Georges Méliès.[89] It was profoundly influential on later filmmakers, bringing creativity to the cinematic medium and offering fantasy for pure entertainment, a rare goal in film at the time. In addition, Méliès's innovative editing and special effects techniques were widely imitated and became important elements of the medium.[90] The film also spurred on the development of cinematic science fiction and fantasy by demonstrating that scientific themes worked on the screen and that reality could be transformed by the camera.[89][91]

1927's Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang, is the first feature-length science fiction film.[92] Though not well received in its time, it is now considered a great and influential film.[93][94][95]

In 1954 Godzilla, directed by Ishirō Honda, began the kaiju subgenre of science fiction film, which feature large creatures of any form, usually attacking a major city or engaging other monsters in battle.[96][97]

1968's 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick and based on the work of Arthur C. Clarke, rose above the mostly B-movie offerings up to that time in scope and quality and greatly influenced later science fiction films.[98][99][100][101] That same year Planet of the Apes, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and based on the 1963 French novel La Planète des Singes by Pierre Boulle, was also popular and critically acclaimed for its vivid depiction of a post-apocalyptic world in which intelligent apes dominate humans.[102]

In 1977 George Lucas began the Star Wars film series with the film now identified as "Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope". The series went on to become a worldwide popular culture phenomenon,[103] and the third highest-grossing film series.[104] From the 1980s science fiction films along with fantasy, horror, and superhero films have dominated Hollywood's big-budget productions.[105] Science fiction films often "crossover" with other genres including animation (WALL-E), gangster (Sky Racket), Western (Serenity), comedy (Spaceballs), war (Enemy Mine), sports (Rollerball), mystery (Minority Report), film noir (Blade Runner), and romantic comedy (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).[106] Science fiction action films feature science fiction elements weaved into action film premises.[107]

Television[edit]

Science fiction and television have always had a close relationship. Television or television-like technologies frequently appeared in science fiction long before television itself became widely available in the late 1940s and early 1950s; perhaps most famously in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.[108] The first known science fiction television program was produced by the BBC's pre-war BBC Television service. On 11 February 1938 a thirty-five-minute adapted extract of the play RUR, written by the Czech playwright Karel Čapek, was broadcast live from the BBC's Alexandra Palace studios.[109] The first popular science fiction program on American television was the children's adventure serial Captain Video and His Video Rangers, which ran from June 1949 to April 1955.[110]

The Twilight Zone, produced and narrated by Rod Serling, who also wrote or co-wrote most of the episodes, ran from 1959 to 1964. It featured fantasy and horror as well as science fiction, with each episode being a complete story.[111][112] Critics have ranked it as one of the best TV programs of any genre.[113][114] The Jetsons, while intended as comedy and only running for one season (1962–1963), predicted many inventions now in common use: flatscreen television, newspapers on a computer-like screen, computer viruses, video chat, tanning beds, home treadmills and more.[115]

In 1963 the time travel themed Doctor Who premiered on BBC Television. The original series ran until 1989 and was revived in 2005. It has been extremely popular worldwide and has greatly influenced later TV science fiction programs, as well as popular culture.[116][117] Star Trek, produced by Gene Roddenberry, premiered in 1966 on NBC Television and ran through the 1969 season. It combined elements of space opera and space Western. Although only mildly successful it gained popularity through later syndication and eventually spawned a very popular and influential franchise through films, later programs, and novels; as well as by intense fan interest.[118][119][120] Other programs in the 1960s included The Prisoner,[121] The Outer Limits,[122] and Lost in Space.[123][124]

In 1987 Star Trek: The Next Generation began a torrent of new shows, including three further Star Trek continuation shows (Deep Space 9, Voyager and Enterprise) and Babylon 5.[125] Red Dwarf, a comic science fiction series aired on BBC Two between 1988 and 1999, and on Dave since 2009, gaining a cult following.[126] To date, eleven full series of the show plus one "special" miniseries have aired. The latest series, dubbed Red Dwarf XII, started airing in October 2017.[127] The X-Files, which featured UFOs and conspiracy theories, was created by Chris Carter and broadcast by Fox Broadcasting Company from 1993 to 2002.[128][129] Stargate, a film about ancient astronauts and interstellar teleportation, was released in 1994. Stargate SG-1 premiered in 1997 and ran for 10 seasons. Spin-off series included Stargate Infinity, Stargate Atlantis, and Stargate Universe.[130]

Social influence[edit]

Science fiction's great rise in popularity during the first half of the twentieth century was closely tied to the respect paid to science at that time, as well as the rapid pace of technological innovation and new inventions.[131] Science fiction has almost always predicted scientific and technological progress. Some works predict this leading to improvements in life and society, for instance the stories of Arthur C. Clarke and the Star Trek series. While others warn about possible negative consequences, for instance H.G. Wells' The Time Machine and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.[132]

Brian Aldiss described science fiction as "cultural wallpaper."[133] Evidence for this widespread influence can be found in a trend for academic researchers to employ science fiction as a tool for advocacy, generating cultural insights, and assisting teaching and learning across a range of academic disciplines not limited to the natural sciences.[134]

The National Science Foundation conducted surveys of "Public Attitudes and Public Understanding" of "Science Fiction and Pseudoscience."[135] They write that "Interest in science fiction may affect the way people think about or relate to science....one study found a strong relationship between preference for science fiction novels and support for the space program...The same study also found that students who read science fiction are much more likely than other students to believe that contacting extraterrestrial civilizations is both possible and desirable."[136] Carl Sagan wrote: "Many scientists deeply involved in the exploration of the solar system (myself among them) were first turned in that direction by science fiction. And the fact that some of that science fiction was not of the highest quality is irrelevant. Ten year‐olds do not read the scientific literature".[137]

Sense of wonder[edit]

Science fiction is often said to generate a "sense of wonder." Science fiction editor and critic David Hartwell writes: "Science fiction’s appeal lies in combination of the rational, the believable, with the miraculous. It is an appeal to the sense of wonder."[138] Carl Sagan said: "One of the great benefits of science fiction is that it can convey bits and pieces, hints and phrases, of knowledge unknown or inaccessible to the reader ... works you ponder over as the water is running out of the bathtub or as you walk through the woods in an early winter snowfall."[137] Isaac Asimov in 1967 commenting on the changes then occurring in SF wrote: "And because today’s real life so resembles day-before-yesterday’s fantasy, the old-time fans are restless. Deep within, whether they admit it or not, is a feeling of disappointment and even outrage that the outer world has invaded their private domain. They feel the loss of a 'sense of wonder' because what was once truly confined to 'wonder' has now become prosaic and mundane."[139]

As protest literature[edit]

Science fiction has sometimes been used as a means of social protest. James Cameron’s film Avatar was intended as a protest against imperialism, and specifically against the European colonization of the Americas.[140] Its images were used by, among others, Palestinians in their protest against Israel.[141]

Robots, artificial humans, human clones, intelligent computers, and their possible conflicts with humans has been a major theme of science fiction since the publication of Frankenstein. Some critics have seen this as reflecting authors’ concerns over the social alienation seen in modern society.[142]

Feminist science fiction poses questions about social issues such as how society constructs gender roles, the role reproduction plays in defining gender and the unequal political and personal power of men over women. Some of the most notable feminist science fiction works have illustrated these themes using utopias to explore a society in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, or dystopias to explore worlds in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus asserting a need for feminist work to continue.[143]

Libertarian science fiction focuses on the politics and the social order implied by right libertarian philosophies with an emphasis on individualism and private property, and in some cases anti-statism.[144]

Climate fiction, or "cli-fi" deals with issues concerning climate change and global warming.[145][146] University courses on literature and environmental issues may include climate change fiction in their syllabi,[147] as well as it being discussed by the media, outside of SF fandom.[148]

Comic science fiction often satirizes and criticizes present-day society, as well as sometimes making fun of the conventions and clichés of serious science fiction.[149][150]

Science fiction studies[edit]

The study of science fiction, or science fiction studies, is the critical assessment, interpretation, and discussion of science fiction literature, film, new media, fandom, and fan fiction. Science fiction scholars study science fiction to better understand it and its relationship to science, technology, politics, and culture-at-large. Science fiction studies has a long history, dating back to the turn of the 20th century, but it was not until later that science fiction studies solidified as a discipline with the publication of the academic journals Extrapolation (1959), Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction (1972), and Science Fiction Studies (1973), and the establishment of the oldest organizations devoted to the study of science fiction, the Science Fiction Research Association and the Science Fiction Foundation, in 1970. The field has grown considerably since the 1970s with the establishment of more journals, organizations, and conferences with ties to the science fiction scholarship community, and science fiction degree-granting programs such as those offered by the University of Liverpool and Kansas University.

Scholar and science fiction critic George Edgar Slusser said that science fiction "is the one real international literary form we have today, and as such has branched out to visual media, interactive media and on to whatever new media the world will invent in the 21st century... crossover issues between the sciences and the humanities are crucial for the century to come."[151]

Classification[edit]

Science Fiction has historically been sub-divided between hard science fiction and soft science fiction – with the division centering on the feasibility of the science central to the story.[152] However, this distinction has come under increasing scrutiny in the 21st century. Authors including Tade Thompson and Jeff VanderMeer have pointed out that stories that focus explicitly on physics, astronomy, mathematics, and engineering tend to be considered "hard", while stories that focus on botany, mycology, zoology or the social sciences tend to be categorized as, "soft," regardless of the relative rigor of the science.[153]

Max Gladstone defined hard SF as being, "SF where the math works," but pointed out that this ends up with stories that seem, "weirdly dated," as scientific paradigms shift over time. Aliette de Bodard argued that there was a risk in the categorization that authors' work would be dismissed as not being, "proper," SF. Michael Swanwick dismissed the traditional definition of hard SF altogether, instead saying that it was defined by characters striving to solve problems, "in the right way – with determination, a touch of stoicism, and the consciousness that the universe is not on his or her side."[153]

Ursula K. Leguin took a more traditional view on the difference between "hard" and "soft" SF but arrived at a divergent value-judgment from the one implied by de Bodard, saying, "The "hard" science fiction writers dismiss everything except, well, physics, astronomy, and maybe chemistry. Biology, sociology, anthropology—that's not science to them, that's soft stuff. They're not that interested in what human beings do, really. But I am. I draw on the social sciences a great deal."[154]

As serious literature[edit]

Respected authors of main-stream literature have written science fiction. Mary Shelley wrote a number of science fiction novels including Frankenstein, and is considered a major writer of the Romantic Age.[156] Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) is often listed as one of England's most important novels, both for its criticism of modern culture and its prediction of future trends including reproductive technology and social engineering.[157][158][159][160] Doris Lessing, who was later awarded the Nobel Prize in literature, wrote a series of SF novels, Canopus in Argos, which depict the efforts of more advanced species and civilizations to influence those less advanced including humans on Earth.[161][162][163][164] Kurt Vonnegut was a highly respected American author whose works contain science fiction premises or themes.[165][166][167] Science fiction authors whose works are considered to be serious literature include Ray Bradbury,[168] Arthur C. Clarke (especially for Childhood's End),[169][170] and Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, writing under the name Cordwainer Smith.[171]

In her much reprinted essay "Science Fiction and Mrs Brown,"[172] Ursula K. Le Guin first asks: "Can a science fiction writer write a novel?"; and answers: "I believe that all novels, ... deal with character, and that it is to express character – not to preach doctrines, sing songs, or celebrate the glories of the British Empire, that the form of the novel, so clumsy, verbose, and undramatic, so rich, elastic, and alive, has been evolved ... The great novelists have brought us to see whatever they wish us to see through some character. Otherwise they would not be novelists, but poets, historians, or pamphleteers."

Tom Shippey asks: "What is its relationship to fantasy fiction, is its readership still dominated by male adolescents, is it a taste which will appeal to the mature but non-eccentric literary mind?"[173] He compares George Orwell's Coming Up for Air with Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth's The Space Merchants and concludes that the basic building block and distinguishing feature of a science fiction novel is the presence of the novum, a term Darko Suvin adapts from Ernst Bloch and defines as "a discrete piece of information recognizable as not-true, but also as not-unlike-true, not-flatly- (and in the current state of knowledge) impossible."[174]

Orson Scott Card, best known for his 1985 science fiction novel Ender's Game and also an author of non-SF fiction, has postulated that in science fiction the message and intellectual significance of the work is contained within the story itself and, therefore, there need not be stylistic gimmicks or literary games; but that some writers and critics confuse clarity of language with lack of artistic merit. In Card's words: "...a great many writers and critics have based their entire careers on the premise that anything that the general public can understand without mediation is worthless drivel. [...] If everybody came to agree that stories should be told this clearly, the professors of literature would be out of a job, and the writers of obscure, encoded fiction would be, not honored, but pitied for their impenetrability."[175]

Science fiction author and physicist Gregory Benford has declared that: "SF is perhaps the defining genre of the twentieth century, although its conquering armies are still camped outside the Rome of the literary citadels."[176] Jonathan Lethem in an essay published in the Village Voice entitled "Close Encounters: The Squandered Promise of Science Fiction" suggests that the point in 1973 when Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow was nominated for the Nebula Award and was passed over in favor of Arthur C. Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama stands as "a hidden tombstone marking the death of the hope that SF was about to merge with the mainstream."[177] Among the responses to Lethem was one from the editor of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction who asked: "When is it [the SF genre] ever going to realize it can't win the game of trying to impress the mainstream?"[178]

David Barnett has remarked:[179] "The ongoing, endless war between "literary" fiction and "genre" fiction has well-defined lines in the sand. Genre's foot soldiers think that literary fiction is a collection of meaningless but prettily drawn pictures of the human condition. The literary guard consider genre fiction to be crass, commercial, whizz-bang potboilers. Or so it goes." He has also pointed out that there are books such as The Road by Cormac McCarthy, Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, The Gone-Away World by Nick Harkaway, The Stone Gods by Jeanette Winterson and Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood, which use recognizable science fiction tropes, but whose authors and publishers do not market them as science fiction.[180]

Community[edit]

Authors[edit]

Science fiction is being written worldwide by a diverse population of authors. According to 2013 statistics by the science fiction publisher Tor Books, men outnumber women by 78% to 22% among submissions to the publisher.[181] A controversy about voting slates in the 2015 Hugo Awards highlighted tensions in the science fiction community between a trend of increasingly diverse works and authors being honored by awards, and a backlash by groups of authors and fans who preferred what they considered more traditional science fiction.[182]

Awards[edit]

Among the most respected awards for science fiction are the Hugo Award, presented by the World Science Fiction Society at Worldcon; the Nebula Award, presented by the SFWA and voted on by the community of authors; and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel and Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award for short fiction. One notable award for science fiction films is the Saturn Award. It is presented annually by The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films.

There are national awards, like Canada's Prix Aurora Awards, regional awards, like the Endeavour Award presented at Orycon for works from the Pacific Northwest, special interest or subgenre awards like the Chesley Award for art or the World Fantasy Award for fantasy. Magazines may organize reader polls, notably the Locus Award.

Conventions, clubs, and organizations[edit]

Conventions (in fandom, shortened as "cons"), are held in cities around the world, catering to a local, regional, national, or international membership. General-interest conventions cover all aspects of science fiction, while others focus on a particular interest like media fandom, filking, etc. Most are organized by volunteers in non-profit groups, though most media-oriented events are organized by commercial promoters. The convention's activities are called the program, which may include panel discussions, readings, autograph sessions, costume masquerades, and other events. Activities occur throughout the convention that are not part of the program. These commonly include a dealer's room, art show, and hospitality lounge (or "con suites").[183]

Conventions may host award ceremonies; Worldcons present the Hugo Awards each year. SF societies, referred to as "clubs" except in formal contexts, form a year-round base of activities for science fiction fans. They may be associated with an ongoing science fiction convention, or have regular club meetings, or both. Most groups meet in libraries, schools and universities, community centers, pubs or restaurants, or the homes of individual members. Long-established groups like the New England Science Fiction Association and the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society have clubhouses for meetings and storage of convention supplies and research materials.[184] The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) was founded by Damon Knight in 1965 as a non-profit organization to serve the community of professional science fiction authors,[185]

Fandom[edit]

Science fiction fandom is the "community of the literature of ideas... the culture in which new ideas emerge and grow before being released into society at large."[2] Members of this community, "fans", are in contact with each other at conventions or clubs, through print or online fanzines, or on the Internet using web sites, mailing lists, and other resources. SF fandom emerged from the letters column in Amazing Stories magazine. Soon fans began writing letters to each other, and then grouping their comments together in informal publications that became known as fanzines.[186] Once they were in regular contact, fans wanted to meet each other, and they organized local clubs. In the 1930s, the first science fiction conventions gathered fans from a wider area.[187]

Fanzines and online fandom[edit]

The first science fiction fanzine, The Comet, was published in 1930.[188] Fanzine printing methods have changed over the decades, from the hectograph, the mimeograph, and the ditto machine, to modern photocopying. Distribution volumes rarely justify the cost of commercial printing. Modern fanzines are printed on computer printers or at local copy shops, or they may only be sent as email. The best known fanzine (or "'zine") today is Ansible, edited by David Langford, winner of numerous Hugo awards. Other fanzines to win awards in recent years include File 770, Mimosa, and Plokta.[189] Artists working for fanzines have risen to prominence in the field, including Brad W. Foster, Teddy Harvia, and Joe Mayhew; the Hugos include a category for Best Fan Artists.[189] The earliest organized fandom online was the SF Lovers community, originally a mailing list in the late 1970s with a text archive file that was updated regularly.[190] In the 1980s, Usenet groups greatly expanded the circle of fans online. In the 1990s, the development of the World-Wide Web exploded the community of online fandom by orders of magnitude, with thousands and then literally millions of web sites devoted to science fiction and related genres for all media.[184] Most such sites are small, ephemeral, and/or very narrowly focused, though sites like SF Site and SFcrowsnest offer a broad range of references and reviews about science fiction.

Elements[edit]

Science fiction elements can include:

- Temporal settings in the future, or in alternative histories.[191]

- Spatial settings or scenes in outer space, on other worlds, in subterranean earth, or in parallel universes.[192]

- Aspects of biology in fiction such as aliens, mutants, and enhanced humans.[193][194]

- Speculative or predicted technology such as brain-computer interface, bioengineering, superintelligent computers and robots, ray guns and other advanced weapons.[193][195]

- Undiscovered scientific possibilities such as teleportation, time travel, and faster-than-light travel or communication.[196]

- New and different political and social systems and situations, including utopian, dystopian, post-apocalyptic, or post-scarcity.[197]

- Future history and evolution of humans on earth or on other planets.[198]

- Paranormal abilities such as mind control, telepathy, and telekinesis.[199]

International examples[edit]

- Afrofuturism

- Science fiction in Australia

- Bengali science fiction

- Black science fiction

- Brazilian science fiction

- Canadian science fiction

- Chinese science fiction

- Croatian science fiction

- Czech science fiction and fantasy

- French science fiction

- Japanese science fiction

- Norwegian science fiction

- Science fiction in Poland

- Romanian science fiction

- Russian science fiction and fantasy

- Serbian science fiction

- Spanish science fiction

Subgenres[edit]

- Anthropological science fiction

- Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction

- Biopunk

- Christian science fiction

- Climate fiction

- Comic science fiction

- Cyberpunk

- Dieselpunk

- Dying Earth

- Feminist science fiction

- Gothic science fiction

- Libertarian science fiction

- Military science fiction

- Mundane science fiction

- Planetary romance

- Social science fiction

- Space opera

- Space Western

- Steampunk

Related genres[edit]

See also[edit]

- Outline of science fiction

- History of science fiction

- Timeline of science fiction

- List of science fiction authors

- Extraterrestrials in fiction

- Fan fiction

- Fantastic art

- Futures studies

- List of comic science fiction

- List of religious ideas in science fiction

- List of science fiction and fantasy artists

- List of science fiction films

- List of science fiction novels

- List of science fiction television programs

- List of science fiction themes

- List of science fiction universes

- Planets in science fiction

- Political ideas in science fiction

- Retrofuturism

- Robots in science fiction

- Science fiction comics

- Science fiction fandom

- Science fiction libraries and museums

- Science in science fiction

- Speculative evolution

- Technology in science fiction

- Time travel in fiction

- Weapons in science fiction

References[edit]

- ^ Marg Gilks; Paula Fleming & Moira Allen (2003). "Science Fiction: The Literature of Ideas". WritingWorld.com.

- ^ a b von Thorn, Alexander (August 2002). "Aurora Award acceptance speech". Calgary, Alberta.

- ^ James Blish, More Issues at Hand, Advent: Publishers, 1970. Pg. 99. Also in Jesse Sheidlower, "Dictionary citations for the term «hard science fiction»". Jessesword.com. Last modified 6 July 2008.

- ^ Asimov, "How Easy to See the Future!", Natural History, 1975

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A.; Cyril Kornbluth; Alfred Bester; Robert Bloch (1959). The Science Fiction Novel: Imagination and Social Criticism. University of Chicago: Advent Publishers.

- ^ Del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction 1926–1976. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-25452-8.

- ^ Knight, Damon Francis (1967). In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction. Advent Publishing, Inc. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-911682-31-1.

- ^ Glassy, Mark C. (2001). The Biology of Science Fiction Cinema. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0998-3.

- ^ "Forrest J Ackerman, 92; Coined the Term 'Sci-Fi'". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Whittier, Terry (1987). Neo-Fan's Guidebook.

- ^ Scalzi, John (2005). The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (1998). "Harlan Ellison's responses to online fan questions at ParCon". Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""Sci fi" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""SF" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^

- Fredericks, S.C.: "Lucian's True History as SF", Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (March 1976), pp. 49–60

- Georgiadou, Aristoula & Larmour, David H.J.: "Lucian's Science Fiction Novel True Histories. Interpretation and Commentary", Mnemosyne Supplement 179, Leiden 1998, ISBN 90-04-10667-7, Introduction

- Grewell, Greg: "Colonizing the Universe: Science Fictions Then, Now, and in the (Imagined) Future", Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2001), pp. 25–47 (30f.)

- Gunn, James E., The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Viking, 1988, ISBN 978-0-670-81041-3, p. 249, calls it "Proto-Science Fiction."

- Swanson, Roy Arthur: "The True, the False, and the Truly False: Lucian's Philosophical Science Fiction", Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Nov. 1976), pp. 227–239

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 209–13. ISBN 978-1-86064-983-7.

- ^ a b Richardson, Matthew (2001). The Halstead Treasury of Ancient Science Fiction. Rushcutters Bay, New South Wales: Halstead Press. ISBN 978-1-875684-64-9. (cf. "Once Upon a Time". Emerald City (85). September 2002. Retrieved 17 September 2008.)

- ^ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World [1])

- ^ Creator and presenter: Carl Sagan (12 October 1980). "The Harmony of the Worlds". Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. PBS.

- ^

- White, William (September 2009). "Science, Factions, and the Persistent Specter of War: Margaret Cavendish's Blazing World". Intersect: The Stanford Journal of Science, Technology and Society. 2 (1): 40–51. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Murphy, Michael (2011). A Description of the Blazing World. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-035-3.

- "Margaret Cavendish's The Blazing World (1666)". Skulls in the Stars. 2 January 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Robin Anne Reid (2009). Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy: Overviews. ABC-CLIO. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-313-33591-4.

- ^ a b "Science Fiction". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^

- Khanna, Lee Cullen. "The Subject of Utopia: Margaret Cavendish and Her Blazing-World." Utopian and Science Fiction by Women: World of Difference. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1994. 15–34.

- ^

- "Carl Sagan on Johannes Kepler's persecution". YouTube. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Asimov, Isaac (1977). The Beginning and the End. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-13088-2.

- ^

- Clute, John & Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Mary W. Shelley". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- Wingrove, Aldriss (2001). Billion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction (1973) Revised and expanded as Trillion Year Spree (with David Wingrove)(1986). New York: House of Stratus. ISBN 978-0-7551-0068-2.

- ^ Tresch, John (2002). "Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction". In Hayes, Kevin J. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–132. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1, "The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal". Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2000), Science Fiction, London: Routledge, p. 48

- ^ Renard, Maurice (November 1994), "On the Scientific-Marvelous Novel and Its Influence on the Understanding of Progress", Science Fiction Studies, 21 (64), retrieved 25 January 2016

- ^ Thomas, Theodore L. (December 1961). "The Watery Wonders of Captain Nemo". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 168–177.

- ^ Margaret Drabble (8 May 2014). "Submarine dreams: Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas". New Statesman. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- ^ La obra narrativa de Enrique Gaspar: El Anacronópete (1887), María de los Ángeles Ayala, Universidad de Alicante. Del Romanticismo al Realismo : Actas del I Coloquio de la S. L. E. S. XIX , Barcelona, 24–26 October 1996 / edited by Luis F. Díaz Larios, Enrique Miralles.

- ^ El anacronópete, English translation (2014), www.storypilot.com, Michael Main, accessed April 13, 2016

- ^ Adam Charles Roberts (2000), "The History of Science Fiction", page 48. In Science Fiction, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19204-8.

- ^ Siegel, Mark Richard (1988). Hugo Gernsback, Father of Modern Science Fiction: With Essays on Frank Herbert and Bram Stoker. Borgo Pr. ISBN 978-0-89370-174-1.

- ^ Wagar, W. Warren (2004). H.G. Wells: Traversing Time. Wesleyan University Press. p. 7.

- ^ "HG Wells: A visionary who should be remembered for his social predictions, not just his scientific ones". The Independent. 9 October 2017.

- ^ Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. ISBN 0-8425-0079-0.

- ^ Originally published in the April 1926 issue of Amazing Stories

- ^ Quoted in [1993] in: Stableford, Brian; Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Definitions of SF". In Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. London: Orbit/Little, Brown and Company. pp. 311–314. ISBN 978-1-85723-124-3.

- ^ Edwards, Malcolm J.; Nicholls, Peter (1995). "SF Magazines". In John Clute and Peter Nicholls. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Updated ed.). New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 1066. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ^ Dozois, Gardner; Strahan, Jonathan (2007). The New Space Opera (1st ed.). New York: Eos. p. 2. ISBN 9780060846756.

- ^ Roberts, Garyn G. (2001). "Buck Rogers". In Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat. The Guide To United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ^ Taormina, Agatha (19 January 2005). "A History of Science Fiction". Northern Virginia Community College. Archived from the original on 26 March 2004. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ Codex, Regius (2014). From Robots to Foundations. Wiesbaden/Ljubljana. ISBN 978-1499569827.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1980). In Joy Still Felt: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. chapter 24. ISBN 978-0-385-15544-1.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter (1981) The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Granada, p. 258

- ^ Murphy, Bruce (1996). Benét's reader's encyclopedia. New York: Harper Collins. p. 734. ISBN 0061810886.

- ^ Aaronovitch, David (8 February 2013). "1984: George Orwell's road to dystopia". BBC News. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "Time and Space", Hartford Courant, February 7, 1954, p.SM19

- ^ "Reviews: November 1975", Science Fiction Studies, November 1975

- ^ Aldiss & Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, Victor Gollancz, 1986, p.237

- ^ Sergey Klimanov's Home Page. Ivan Yefremov's Works Revised 2004-08-10. Accessed 2006-09-08. Archived April 29, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "OFF-LINE интервью с Борисом Стругацким" (in Russian). Russian Science Fiction & Fantasy. December 2006. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Gale, Floyd C. (October 1960). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–146.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (November 3, 2016). "Why 'Starship Troopers' May Be Too Controversial to Adapt Faithfully". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (November 3, 2016). "Four things that we want to see in the Starship Troopers reboot". The Verge. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ Slusser, George E. (1987). Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction Alternatives. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 210–220. ISBN 9780809313747.

- ^ Mikołajewska, Emilia; Mikołajewski, Dariusz (May 2013). "Exoskeletons in Neurological Diseases – Current and Potential Future Applications". Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 20 (2): 228 Fig. 2.

- ^ Weiss, Peter. "Dances with Robots". Science News Online. Archived from the original on January 16, 2006. Retrieved March 4, 2006.

- ^ Mike Ashley; Michael Ashley (14 May 2007). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970–1980. Liverpool University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- ^ McGuirk, Carol (1992). "The 'New' Romancers". In Slusser, George Edgar; Shippey, T. A. Fiction 2000. University of Georgia Press. pp. 109–125. ISBN 9780820314495.

- ^ Caroti, Simone (2011). The Generation Starship in Science Fiction. McFarland. p. 156. ISBN 9780786485765.

- ^ Peter Swirski (ed), The Art and Science of Stanislaw Lem, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-7735-3047-9

- ^ Stanislaw Lem, Fantastyka i Futuriologia, Wedawnictwo Literackie, 1989, vol. 2, p. 365

- ^ Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia, fourth edition (1996), p. 590.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2000). Science Fiction. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–90. ISBN 978-0-415-19204-0.

- ^ Sammon, Paul M. (1996). Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner. London: Orion Media. p. 49. ISBN 0-06-105314-7.

- ^ Stover, Leon E. "Anthropology and Science Fiction" Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1973)

- ^ Reid, Suzanne Elizabeth (1997). Presenting Ursula Le Guin. New York, New York, USA: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-4609-9, pp=9, 120

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte (1984). Ursula K. Le Guin (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7393-4.,pp=44–50

- ^ "C. J. Cherryh, Science Fiction, and the Soft Sciences". Dancing Badger. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ "Brilliant Literature is Unearthed in Cherryh's Novels". Los Angeles Daily News. November 29, 1987. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

CJ Cherryh will be the guest of honor at LOSCON 14, this year's annual convention for Los Angeles-area science fiction and fantasy fans.

- ^ Cherryh, C. J. "Progress Report". Cherryh.com. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ Brave New World of Chinese Science Fiction

- ^ Science Fiction, Globalization, and the People's Republic of China

- ^ Fitting, Peter (July 1991). "The Lessons of Cyberpunk". In Penley, C.; Ross, A. Technoculture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 295–315

- ^ Schactman, Noah (May 23, 2008). "26 Years After Gibson, Pentagon Defines 'Cyberspace'". Wired.

- ^ Hayward, Philip (1993). Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. British Film Institute. pp. 180–204. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Walton, Jo (March 31, 2009). "Weeping for her enemies: Lois McMaster Bujold's Shards of Honor". Tor.com. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ Loud Achievements: Lois McMaster Bujold's Science Fiction in New York Review of Science Fiction, October 1998 (Number 122)

- ^ Mustich, James (2008-10-13). "Interviews – Neal Stephenson: Anathem – A Conversation with James Mustich, Editor-in-Chief of the Barnes & Noble Review". barnesandnoble.com. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

I’d had a similar reaction to yours when I’d first read The Origin of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and that, combined with the desire to use IT, were two elements from which Snow Crash grew.

- ^ 2015 Hugo Awards

- ^ Chen, Andrea. "Out of this world: Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin is Asia's first writer to win Hugo award for best novel." South China Morning Post. Monday 24 August 2015. Retrieved on 27 August 2015.

- ^ Bebergal, Peter (August 26, 2007). "The age of steampunk:Nostalgia meets the future, joined carefully with brass screws". Boston Globe.

- ^ Pulver, David L. (1998). GURPS Bio-Tech. Steve Jackson Games. ISBN 978-1-55634-336-0.

- ^ Paul Taylor. "Fleshing Out the Maelstrom: Biopunk and the Violence of Information". Journal of Media and Culture.

- ^ "How sci-fi moves with the times". BBC News. 18 March 2009.

- ^ Walter, Damien (2 May 2008). "The really exciting science fiction is boring". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (2008), A Short History of Film, Rutgers University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-8135-4475-5

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay (1 October 2012), 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2012, Octopus Publishing Group, p. 20, ISBN 978-1-84403-733-9

- ^ Kawin, Bruce F. (January 1992), How Movies Work, University of California Press, p. 51, ISBN 978-0-520-07696-9

- ^ SciFi Film History - Metropolis (1927) – Though most agree that the first science fiction film was Georges Méliès' A Trip to the Moon (1902), Metropolis (1926) is the first feature length outing of the genre. (scififilmhistory.com, retrieved 15 May 2013)

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". empireonline.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 100 Silent Era Films". silentera.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound September 2012 issue. British Film Institute. 1 August 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]". dic-pixiv. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ^ "A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]". Hokkai-Gakuen University. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ^ Kazan, Casey (10 July 2009). "Ridley Scott: "After 2001 -A Space Odyssey, Science Fiction is Dead"". Dailygalaxy.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ In Focus on the Science Fiction Film, edited by William Johnson. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

- ^ DeMet, George D. "2001: A Space Odyssey Internet Resource Archive: The Search for Meaning in 2001". Palantir.net (originally an undergrad honors thesis). Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "This Day in Science Fiction History – 2001: A Space Odyssey | Discover Magazine". Blogs.discovermagazine.com. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Russo, Joe; Landsman, Larry; Gross, Edward (2001). Planet of the Apes Revisited: The Behind-The Scenes Story of the Classic Science Fiction Saga (1st ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312252390.

- ^ "Star Wars – Box Office History". The Numbers. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Movie Franchises". The Numbers. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950–1982, Bradley Schauer, Wesleyan University Press, Jan 3, 2017, page 7

- ^ Science Fiction Film: A Critical Introduction, Keith M. Johnston, Berg, May 9, 2013, pages 24–25. examples are the ones given by this book

- ^ "The Fifth Element (1997) – Trailers, Reviews, Synopsis, Showtimes and Cast". AllMovie. 7 May 1997. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Science Fiction TV, J. P. Telotte, Routledge, Mar 26, 2014, pages 112, 179

- ^ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction television reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6.

- ^ Suzanne Williams-Rautiolla (2005-04-02). "Captain Video and His Video Rangers". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "The Twilight Zone [TV Series] [1959–1964]". Allmovie. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ Stanyard, Stewart T. (2007). Dimensions Behind the Twilight Zone : A Backstage Tribute to Television's Groundbreaking Series ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Toronto: ECW press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1550227444.

- ^ "TV Guide Names Top 50 Shows". CBS News. CBS Interactive. April 26, 2002. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ "101 Best Written TV Series List". Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ O'Reilly, Terry (May 24, 1014). "21st Century Brands". Under the Influence. Season 3. Episode 21. Transcript of the original source. Event occurs at time 2:07. CBC Radio One. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

The series had lots of interesting devices that marveled us back in the 60s. In episode one, we see wife Jane doing exercises in front of a flatscreen television. In another episode, we see George Jetson reading the newspaper on a screen. Can anyone say computer? In another, Boss Spacely tells George to fix something called a "computer virus." Everyone on the show uses video chat, foreshadowing Skype and Face Time. There is a robot vacuum cleaner, foretelling the 2002 arrival of the iRobot Roomba vacuum. There was also a tanning bed used in an episode, a product that wasn't introduced to North America until 1979. And while flying space cars that have yet to land in our lives, the Jetsons show had moving sidewalks like we now have in airports, treadmills that didn't hit the consumer market until 1969, and they had a repairman who had a piece of technology called... Mac.

- ^ "The end of Olde Englande: A lament for Blighty". The Economist. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

"ICONS. A Portrait of England". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2007. - ^ Moran, Caitlin (30 June 2007). "Doctor Who is simply masterful". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

[Doctor Who] is as thrilling and as loved as Jolene, or bread and cheese, or honeysuckle, or Friday. It's quintessential to being British.

- ^ Roddenberry, Gene (March 11, 1964). Star Trek Pitch, first draft. Accessed at LeeThomson.myzen.co.uk.

- ^ "STARTREK.COM: Universe Timeline". Startrek.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Okada, Michael; Okadu, Denise (November 1, 1996). Star Trek Chronology: The History of the Future. ISBN 978-0-671-53610-7.

- ^ British Science Fiction Television: A Hitchhiker's Guide, John R. Cook, Peter Wright, I.B.Tauris, Jan 6, 2006, page 9

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 100 Greatest Episodes of All Time". TV Guide (June 28 – July 4). 1997.

- ^ Gowran, Clay. "Nielsen Ratings Are Dim on New Shows." Chicago Tribune. Oct. 11, 1966: B10.

- ^ Gould, Jack. "How Does Your Favorite Rate? Maybe Higher Than You Think." New York Times. Oct. 16, 1966: 129.

- ^

- Richardson, David (July 1997). "Dead Man Walking". Cult Times. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- Nazarro, Joe. "The Dream Given Form". TV Zone Special (#30).

- ^ "Worldwide Press Office – Red Dwarf on DVD". BBC. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Red Dwarf XII". Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Bischoff, David (December 1994). "Opening the X-Files: Behind the Scenes of TV's Hottest Show". Omni. 17 (3).

- ^ Goodman, Tim (January 18, 2002). "'X-Files' Creator Ends Fox Series". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ^ Sumner, Darren (10 May 2011). "Smallville bows this week – with Stargate's world record". GateWorld. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America, John Cheng, University of Pennsylvania Press, Mar 19, 2012 pages 1–12.

- ^ The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders, Volume 2, Gary Westfahl, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005

- ^ Aldiss, Brian; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-575-03943-8.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin; Cheer, Karen Diane (2017). "Human Culture and Science Fiction: A Review of the Literature, 1980–2016". SAGE Open. 7 (3): 215824401772369. doi:10.1177/2158244017723690. ISSN 2158-2440.

- ^ National Science Foundation survey: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding. Science Fiction and Pseudoscience. Archived 16 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sims (1982). "The Impact of Science Fiction on Attitudes Toward Technology". In Emme, Eugene Morlock. Science fiction and space futures: past and present. Univelt. ISBN 978-0-87703-173-4.

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl (1978-05-28). "Growing up with Science Fiction". The New York Times. p. SM7. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Hartwell, David. Age of Wonders (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985, page 42)

- ^ Asimov, Isaac. ‘Forward 1 – The Second Revolution’ in Ellison, Harlan (ed.). Dangerous Visions (London: Victor Gollancz, 1987)

- ^ Gross, Terry (February 18, 2010). "James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination". National Public Radio. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ Science Fiction Film, Television, and Adaptation: Across the Screens, Jay Telotte, Gerald Duchovnay, Routledge, Aug 2, 2011

- ^ Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films, Per Schelde, NYU Press, 1994, pages 1–10

- ^ Elyce Rae Helford, in Westfahl, Gary. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Greenwood Press, 2005: 289–290.

- ^ Raymond, Eric. "A Political History of SF". Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ Glass, Rodge (May 31, 2013). "Global Warning: The Rise of 'Cli-fi'" retrieved March 3, 2016

- ^ Bloom, Dan (10 March 2015). "'Cli-Fi' Reaches into Literature Classrooms Worldwide". Inter Press Service News Agency. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ PÉREZ-PEÑA, RICHARD. "College Classes Use Arts to Brace for Climate Change". New York Times (April 1, 2014 pg A12). Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Tuhus-Dubrow, Rebecca (Summer 2013). "Cli-Fi: Birth of a Genre". Dissent. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ The Animal Fable in Science Fiction and Fantasy, Bruce Shaw, McFarland, 2010, page 19

- ^ "Comedy Science Fiction". Sfbook.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Lovekin, Kris (April 2000). "Reading Ahead". Fiat Lux. University of California, Riverside.

- ^ https://www.bcls.lib.nj.us/genre-science-fiction

- ^ a b https://www.tor.com/2017/02/20/ten-authors-on-the-hard-vs-soft-science-fiction-debate/

- ^ https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/a15871082/ursula-k-le-guin-life/

- ^ Browne, Max. "Theodor Richard Edward von Holst". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (subscription required) Retrieved on 20 April 2008.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, ix–xi, 120–21; Schor, Introduction to Cambridge Companion, 1–5; Seymour, 548–61.

- ^ Ludwig von Mises (1944). Bureaucracy, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p 110

- ^ "100 Best Novels". Random House. 1999. Retrieved 23 June 2007. This ranking was by the Modern Library Editorial Board of authors.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (12 October 2003). "100 greatest novels of all time". London: Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 26 October 2012

- ^ Hazelton, Lesley (1982-07-25). "Doris Lessing on Feminism, Communism and 'Space Fiction'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ Galin, Müge (1997). Between East and West: Sufism in the Novels of Doris Lessing. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7914-3383-6.

- ^ Lessing, Doris (1994) [1980]. "Preface". The Sirian Experiments. London: Flamingo. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-00-654721-1.

- ^ Donoghue, Denis (22 September 1985). "Alice, The Radical Homemaker". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Allen, William R. "A Brief Biography of Kurt Vonnegut". Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Allen, William R. (1991). Understanding Kurt Vonnegut. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-722-1.

- ^ Banach, Je (April 11, 2013). "Laughing in the Face of Death: A Vonnegut Roundtable". The Paris Review. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Jonas, Gerald (June 6, 2012). "Ray Bradbury, Master of Science Fiction, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ Barlowe, Wayne Douglas (1987). Barlowe's Guide to Extraterrestrials. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89480-500-2.

- ^ Baxter, John (1997). "Kubrick Beyond the Infinite". Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. Basic Books. pp. 199–230. ISBN 0-7867-0485-3.

- ^ Gary K. Wolfe and Carol T. Williams, "The Majesty of Kindness: The Dialectic of Cordwainer Smith”, Voices for the Future: Essays on Major Science Fiction Writers, Volume 3, Thomas D. Clareson editor, Popular Press, 1983, pages 53–72.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (1976) "Science Fiction and Mrs Brown," in The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, Perennial HarperCollins, Revised edition 1993; in Science Fiction at Large (ed. Peter Nicholls), Gollancz, London, 1976; in Explorations of the Marvellous (ed. Peter Nicholls), Fontana, London, 1978; in Speculations on Speculation. Theories of Science Fiction (eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria), The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Maryland, 2005.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (1991) Fictional Space. Essays on Contemporary Science Fiction, page 2, Humanities Press International, Inc., NJ

- ^ Suvin, Darko (1979) Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre, New Haven, pp. 63–84.

- ^ Card, O.:Ender's Game, Introduction. Macmillan, 2006

- ^ Benford, Gregory (1998) "Meaning-Stuffed Dreams:Thomas Disch and the future of SF", New York Review of Science Fiction, September, Number 121, Vol. 11, No. 1

- ^ Lethem, Jonathan (1998), "Close Encounters: The Squandered Promise of Science Fiction", Village Voice, June. Also reprinted in a slightly expanded version under the title "Why Can't We All Live Together?: A Vision of Genre Paradise Lost" in the New York Review of Science Fiction, September 1998, Number 121, Vol 11, No. 1.

- ^ Van Gelder, Gordon (1998) "Editorial," Fantasy and Science Fiction, October/November v95 #4/5 No. 567

- ^ Barnett, David. "Gaiman's choice: shouldn't good writing tell a story too?," The Guardian, London, 23 June 2010,

- ^ Barnett, David. "Science fiction: the genre that dare not speak its name," The Guardian, London, 28 January 2009.

- ^ Crisp, Julie (10 July 2013). "SEXISM IN GENRE PUBLISHING: A PUBLISHER'S PERSPECTIVE". Tor Books. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015. (See full statistics)

- ^ McCown, Alex (6 April 2015). "This year's Hugo Award nominees are a messy political controversy". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Lawrence Watt-Evans (15 March 1988). "What Are Science Fiction Conventions Like?". Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b Glyer, Mike (November 1998). "Is Your Club Dead Yet?". File 770 (127).

- ^ "Information About SFWA". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Inc. Archived from the original on 24 December 2005. Retrieved 16 January 2006.

- ^ Wertham, Fredric (1973). The World of Fanzines. Carbondale & Evanston: Southern Illinois University Press.

- ^ "Fancyclopedia I: C – Cosmic Circle". fanac.org. 12 August 1999. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Hansen, Rob (13 August 2003). "British Fanzine Bibliography". Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Hugo Awards by Category". World Science Fiction Society. 26 July 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Lynch, Keith (14 July 1994). "History of the Net is Important". Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Bunzl, Martin (June 2004). "Counterfactual History: A User's Guide". American Historical Review. Archived from the original on 2004-10-13. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ Sterling, Bruce. "Science fiction" in Encyclopædia Britannica 2008 [2]

- ^ a b Westfahl, Gary (2005). "Aliens in Space". In Gary Westfahl. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 1. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-313-32951-7.

- ^ Parker, Helen N. (1977). Biological Themes in Modern Science Fiction. UMI Research Press.

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (1990). How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Writer's Digest Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89879-416-8.

- ^ Peter Fitting (2010), "Utopia, dystopia, and science fiction", in Gregory Claeys, The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature, Cambridge University Press, pp. 138–139

- ^ Hartwell, David G. (1996). Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction. Tor Books. pp. 109–131. ISBN 978-0-312-86235-0.

- ^ Ashley, M. (April, 1989). The Immortal Professor, Astro Adventures No.7, p.6.

- ^ H. G. Stratmann. Using Medicine in Science Fiction: The SF Writer’s Guide to Human Biology. Springer, 2015. p. 227. ISBN 9783319160153.

Sources[edit]

- Aldiss, Brian. Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction, 1973.

- Aldiss, Brian, and Wingrove, David. Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, revised and updated edition, 1986.

- Amis, Kingsley. New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction, 1958.

- Barron, Neil, ed. Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction (5th ed.). Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited, 2004. ISBN 1-59158-171-0.

- Broderick, Damien. Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction. London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

- Clute, John Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Dorling Kindersley, 1995. ISBN 0-7513-0202-3.

- Clute, John and Peter Nicholls, eds., The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing, 1979. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- Clute, John and Peter Nicholls, eds., The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Press, 1995. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- Disch, Thomas M. The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of. New York: The Free Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-684-82405-5.

- Jameson, Fredric. Archaeologies of the Future: This Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London and New York: Verso, 2005.

- Milner, Andrew. Locating Science Fiction. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012.

- Raja, Masood Ashraf, Jason W. Ellis and Swaralipi Nandi. eds., The Postnational Fantasy: Essays on Postcolonialism, Cosmopolitics and Science Fiction. McFarland 2011. ISBN 978-0-7864-6141-7.

- Reginald, Robert. Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, 1975–1991. Detroit, MI/Washington, D.C./London: Gale Research, 1992. ISBN 0-8103-1825-3.

- Scholes, Robert E.; Rabkin, Eric S. (1977). Science fiction: history, science, vision. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502174-5.

- Suvin, Darko. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: on the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre. New Haven : Yale University Press, 1979.

- Weldes, Jutta, ed. To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links between Science Fiction and World Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-312-29557-X.

- Westfahl, Gary, ed. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders (three volumes). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005.

- Wolfe, Gary K. Critical Terms for Science Fiction and Fantasy: A Glossary and Guide to Scholarship. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986. ISBN 0-313-22981-3.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Science fiction |

- Science Fiction (Bookshelf) at Project Gutenberg

- SF Hub—resources for science-fiction research, created by the University of Liverpool Library

- Science fiction fanzines (current and historical) online

- SFWA "Suggested Reading" list

- Science Fiction Museum & Hall of Fame

- Science Fiction Research Association

- A selection of articles written by Mike Ashley, Iain Sinclair and others, exploring 19th-century visions of the future. from the British Library's Discovering Literature website.

- Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy at Toronto Public Library

- Science Fiction Studies' Chronological Bibliography of Science Fiction History, Theory, and Criticism