Organization

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

An organization or organisation is an entity comprising multiple people, such as an institution or an association, that has a particular purpose.

The word is derived from the Greek word organon, which means tool or instrument, musical instrument, and organ.

Contents

Types[edit]

There are a variety of legal types of organisations, including corporations, governments, non-governmental organisations, political organisations, international organisations, armed forces, charities, not-for-profit corporations, partnerships, cooperatives, and educational institutions.

A hybrid organisation is a body that operates in both the public sector and the private sector simultaneously, fulfilling public duties and developing commercial market activities.

A voluntary association is an organisation consisting of volunteers. Such organisations may be able to operate without legal formalities, depending on jurisdiction, including informal clubs.

Organisations may also operate secretly or illegally in the case of secret societies, criminal organisations and resistance movements.

Compare the concept of social groups, which may include non-organizations.[1]

Structures[edit]

The study of organisations includes a focus on optimising organisational structure. According to management science, most human organisations fall roughly into four types:[citation needed]

- Committees or juries

- Ecologies

- Matrix organisations

- Pyramids or hierarchies

Committees or juries[edit]

These consist of a group of peers who decide as a group, perhaps by voting. The difference between a jury and a committee is that the members of the committee are usually assigned to perform or lead further actions after the group comes to a decision, whereas members of a jury come to a decision. In common law countries, legal juries render decisions of guilt, liability and quantify damages; juries are also used in athletic contests, book awards and similar activities. Sometimes a selection committee functions like a jury. In the Middle Ages, juries in continental Europe were used to determine the law according to consensus among local notables.

Committees are often the most reliable way to make decisions. Condorcet's jury theorem proved that if the average member votes better than a roll of dice, then adding more members increases the number of majorities that can come to a correct vote (however correctness is defined). The problem is that if the average member is subsequently worse than a roll of dice, the committee's decisions grow worse, not better; therefore, staffing is crucial.

Parliamentary procedure, such as Robert's Rules of Order, helps prevent committees from engaging in lengthy discussions without reaching decisions.

Ecologies[edit]

This organisational structure promotes internal competition. Inefficient components of the organisation starve, while effective ones get more work. Everybody is paid for what they actually do, and so runs a tiny business that has to show a profit, or they are fired.

Companies who utilise this organisation type reflect a rather one-sided view of what goes on in ecology. It is also the case that a natural ecosystem has a natural border - ecoregions do not, in general, compete with one another in any way, but are very autonomous.

The pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline talks about functioning as this type of organisation in this external article from The Guardian. By:Bastian Batac De Leon.

Matrix organisation[edit]

This organisational type assigns each worker two bosses in two different hierarchies. One hierarchy is "functional" and assures that each type of expert in the organisation is well-trained, and measured by a boss who is super-expert in the same field. The other direction is "executive" and tries to get projects completed using the experts. Projects might be organised by products, regions, customer types, or some other schemes.

As an example, a company might have an individual with overall responsibility for products X and Y, and another individual with overall responsibility for engineering, quality control, etc. Therefore, subordinates responsible for quality control of project X will have two reporting lines.

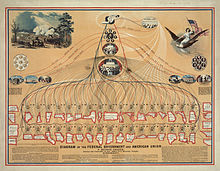

Pyramids or hierarchical[edit]

A hierarchy exemplifies an arrangement with a leader who leads other individual members of the organisation. This arrangement is often associated with basis that there are enough imagine a real pyramid, if there are not enough stone blocks to hold up the higher ones, gravity would irrevocably bring down the monumental structure. So one can imagine that if the leader does not have the support of his subordinates, the entire structure will collapse. Hierarchies were satirised in The Peter Principle (1969), a book that introduced hierarchiology and the saying that "in a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence."

Theories[edit]

In the social sciences, organisations are the object of analysis for a number of disciplines, such as sociology, economics,[2] political science, psychology, management, and organisational communication. The broader analysis of organisations is commonly referred to as organisational structure, organisational studies, organisational behaviour, or organisation analysis. A number of different perspectives exist, some of which are compatible:

- From a functional perspective, the focus is on how entities like businesses or state authorities are used.

- From an institutional perspective, an organisation is viewed as a purposeful structure within a social context.

- From a process-related perspective, an organisation is viewed as an entity is being (re-)organised, and the focus is on the organisation as a set of tasks or actions.

Sociology can be defined as the science of the institutions of modernity; specific institutions serve a function, akin to the individual organs of a coherent body. In the social and political sciences in general, an "organisation" may be more loosely understood as the planned, coordinated and purposeful action of human beings working through collective action to reach a common goal or construct a tangible product. This action is usually framed by formal membership and form (institutional rules). Sociology distinguishes the term organisation into planned formal and unplanned informal (i.e. spontaneously formed) organisations. Sociology analyses organisations in the first line from an institutional perspective. In this sense, organisation is an enduring arrangement of elements. These elements and their actions are determined by rules so that a certain task can be fulfilled through a system of coordinated division of labour.

Economic approaches to organisations also take the division of labour as a starting point. The division of labour allows for (economies of) specialisation. Increasing specialisation necessitates coordination. From an economic point of view, markets and organisations are alternative coordination mechanisms for the execution of transactions.[2]

An organisation is defined by the elements that are part of it (who belongs to the organisation and who does not?), its communication (which elements communicate and how do they communicate?), its autonomy (which changes are executed autonomously by the organisation or its elements?), and its rules of action compared to outside events (what causes an organisation to act as a collective actor?).

By coordinated and planned cooperation of the elements, the organisation is able to solve tasks that lie beyond the abilities of the single elements. The price paid by the elements is the limitation of the degrees of freedom of the elements. Advantages of organisations are enhancement (more of the same), addition (combination of different features) and extension. Disadvantages can be inertness (through co-ordination) and loss of interaction.

Among the theories that are or have been influential are:

- Activity theory is the major theoretical influence, acknowledged by de Clodomir Santos de Morais in the development of Organisation Workshop method.

- Actor–network theory, an approach to social theory and research, originating in the field of science studies, which treats objects as part of social networks.

- Complexity theory and organisations, the use of complexity theory in the field of strategic management and organisational studies.

- Contingency theory, a class of behavioural theory that claims that there is no best way to organize a corporation, to lead a company, or to make decisions.

- Critical management studies, a loose but extensive grouping of theoretically informed critiques of management, business, and organisation, grounded originally in a critical theory perspective

- Economic sociology, studies both the social effects and the social causes of various economic phenomena.

- Enterprise architecture, the conceptual model that defines the coalescence of organisational structure and organisational behaviour.

- Garbage Can Model, describes a model which disconnects problems, solutions and decision makers from each other.

- Principal–agent problem, concerns the difficulties in motivating one party (the "agent"), to act in the best interests of another (the "principal") rather than in his or her own interests

- Scientific management (mainly following Frederick W. Taylor), a theory of management that analyses and synthesises workflows.

- Social entrepreneurship, the process of pursuing innovative solutions to social problems.

- Transaction cost theory, the idea that people begin to organise their production in firms when the transaction cost of coordinating production through the market exchange, given imperfect information, is greater than within the firm.

- Weber's Ideal of Bureaucracy (refer to Max Weber's chapter on "Bureaucracy" in his book Economy and Society)

Leadership[edit]

A leader in a formal, hierarchical organisation, is appointed to a managerial position and has the right to command and enforce obedience by virtue of the authority of his position. However, he must possess adequate personal attributes to match his authority, because authority is only potentially available to him. In the absence of sufficient personal competence, a manager may be confronted by an emergent leader who can challenge his role in the organisation and reduce it to that of a figurehead. However, only authority of position has the backing of formal sanctions. It follows that whoever wields personal influence and power can legitimise this only by gaining a formal position in the hierarchy, with commensurate authority.[3]

Formal organisations[edit]

An organisation that is established as a means for achieving defined objectives has been referred to as a formal organisation. Its design specifies how goals are subdivided and reflected in subdivisions of the organisation. Divisions, departments, sections, positions, jobs, and tasks make up this work structure. Thus, the formal organisation is expected to behave impersonally in regard to relationships with clients or with its members. According to Weber's definition, entry and subsequent advancement is by merit or seniority. Each employee receives a salary and enjoys a degree of tenure that safeguards him from the arbitrary influence of superiors or of powerful clients. The higher his position in the hierarchy, the greater his presumed expertise in adjudicating problems that may arise in the course of the work carried out at lower levels of the organisation. It is this bureaucratic structure that forms the basis for the appointment of heads or chiefs of administrative subdivisions in the organisation and endows them with the authority attached to their position.[4]

Informal organisations[edit]

In contrast to the appointed head or chief of an administrative unit, a leader emerges within the context of the informal organisation that underlies the formal structure. The informal organisation expresses the personal objectives and goals of the individual membership. Their objectives and goals may or may not coincide with those of the formal organisation. The informal organisation represents an extension of the social structures that generally characterise human life – the spontaneous emergence of groups and organisations as ends in themselves.[4]

In prehistoric times, man was preoccupied with his personal security, maintenance, protection, and survival. Now man spends a major portion of his waking hours working for organisations. His need to identify with a community that provides security, protection, maintenance, and a feeling of belonging continues unchanged from prehistoric times. This need is met by the informal organisation and its emergent, or unofficial, leaders.[3]

Leaders emerge from within the structure of the informal organisation. Their personal qualities, the demands of the situation, or a combination of these and other factors attract followers who accept their leadership within one or several overlay structures. Instead of the authority of position held by an appointed head or chief, the emergent leader wields influence or power. Influence is the ability of a person to gain cooperation from others by means of persuasion or control over rewards. Power is a stronger form of influence because it reflects a person's ability to enforce action through the control of a means of punishment.[3]

See also[edit]

- Affinity group

- Business organization

- Coalition

- Collective

- Decentralized autonomous organization

- List of designated terrorist organizations

- List of environmental organizations

- List of general fraternities

- List of international professional associations

- List of trade unions

- Maturity Model

- Multidimensional organization

- Mutual organization

- Organizational psychology

- Organization Workshop

- Organization's goals

- Pacifist organization

- Requisite organization

- Service club

- Size of groups, organizations, and communities

- Umbrella organization

- Voluntary association

References[edit]

- ^

Compare:

Grande, Odd Torgier (1970). Organizations in society: a model framework and its application to organizations in agriculture. Cornell University. p. 164. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

It is also necessary [615513925...] to identify social systems that are not organizations. Many of these are enormously important, but they lack an organization's purposive activity. Among the more conspicuous 'non-organizations' are races and ethnic groups (they have no programs), social classes (their collective identities are not unequivocal and their rosters not exact), cliques and play groups (they lack a collective identity), interest groups such as 'liberals' or 'old-fashioned conservatives' (they have no rosters).

- ^ a b Douma, Sytse; Schreuder, Hein (2013) [1991]. Economic Approaches to Organizations (5th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-273-73529-8.

- ^ a b c Knowles, Henry P.; Saxberg, Borje O. (1971). Personality and Leadership Behavior. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. pp. 884–89. OCLC 118832.

- ^ a b Gibb, Cecil A. (1970). Leadership: Selected Readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140805176. OCLC 174777513.

- General

- Coase, Ronald (1937). "The Nature of the Firm" Economica, 4(16), pp. 386–405.

- Handy, Charles (1990). Inside Organizations: 21 Ideas for Managers. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-20830-3.

- Handy, Charles (2005). Understanding Organizations (4th ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-015603-4.

- Hewlett, Roderic. (2006). The Cognitive leader. Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc.

- Johnson, Richard Arvid (1976). Management, systems, and society : an introduction. Pacific Palisades, Calif.: Goodyear Pub. Co. ISBN 0-87620-540-6. OCLC 2299496.

- Katz, Daniel; Kahn, Robert Louis (1966). The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley. OCLC 255184.

- March, James G.; Simon, Herbert A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-56793-0. OCLC 1329335.

- Marshak, Thomas (1987). "organization theory," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 757–60.

- Mintzberg, Henry (1981). "Organization Design: Fashion or Fit" Harvard Business Review (January February)

- Morgenstern, Julie (1998). Organizing from the Inside Out. Owl Books ISBN 0-8050-5649-1

- Peter, Laurence J. and Raymond Hull. The Peter Principle Pan Books 1970 ISBN 0-330-02519-8

- Rogers, Carl R.; Roethlisberger, Fritz Jules (1990). Barriers and gateways to communication. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review. OCLC 154085959.

- Samson, D., Daft, R. (2005). Management: second Pacific Rim edition. Melbourne, Victoria: Thomson

- Satir, Virginia (1967). Conjoint family therapy; a guide to theory and technique. Palo Alto, Calif: Science and Behavior Books. OCLC 187068.

- Scott, William Richard (2008). Institutions and Organizations (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4129-5090-9.

External links[edit]

| Look up organization in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Organization |

- Research on Organizations: Bibliography Database and Maps

- TheTransitioner.org: a site dedicated to collective intelligence and structure of organizations