Pattern formation

The science of pattern formation deals with the visible, (statistically) orderly outcomes of self-organization and the common principles behind similar patterns in nature.

In developmental biology, pattern formation refers to the generation of complex organizations of cell fates in space and time. Pattern formation is controlled by genes. The role of genes in pattern formation is an aspect of morphogenesis, the creation of diverse anatomies from similar genes, now being explored in the science of evolutionary developmental biology or evo-devo. The mechanisms involved are well seen in the anterior-posterior patterning of embryos from the model organism Drosophila melanogaster (a fruit fly), one of the first organisms to have its morphogenesis studied, and in the eyespots of butterflies, whose development is a variant of the standard (fruit fly) mechanism.

Contents

Examples[edit]

Examples of pattern formation can be found in Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics,[1] and can readily be simulated with Computer graphics, as described in turn below.

Biology[edit]

Biological patterns such as animal markings, the segmentation of animals, and phyllotaxis are formed in different ways.[2]

In developmental biology, pattern formation describes the mechanism by which initially equivalent cells in a developing tissue in an embryo assume complex forms and functions.[3] Embryogenesis, such as of the fruit fly Drosophila, involves coordinated control of cell fates.[4][5][6] Pattern formation is genetically controlled, and often involves each cell in a field sensing and responding to its position along a morphogen gradient, followed by short distance cell-to-cell communication through cell signaling pathways to refine the initial pattern. In this context, a field of cells is the group of cells whose fates are affected by responding to the same set positional information cues. This conceptual model was first described as the French flag model in the 1960s.[7][8] More generally, the morphology of organisms is patterned by the mechanisms of evolutionary developmental biology, such as changing the timing and positioning of specific developmental events in the embryo.[9]

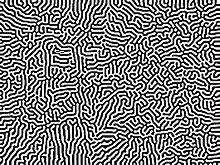

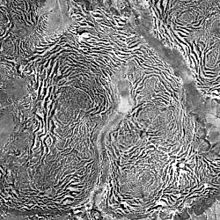

Possible mechanisms of pattern formation in biological systems include the classical reaction-diffusion model proposed by Alan Turing[10] and the more recently found elastic instability mechanism which is thought to be responsible for the fold patterns on the cerebral cortex of higher animals, among other things.[11][12]

Growth of colonies[edit]

Bacterial colonies show a large variety of patterns formed during colony growth. The resulting shapes depend on the growth conditions. In particular, stresses (hardness of the culture medium, lack of nutrients, etc.) enhance the complexity of the resulting patterns.[13] Other organisms such as slime moulds display remarkable patterns caused by the dynamics of chemical signalling.[14]

Vegetation patterns[edit]

Vegetation patterns such as tiger bush[15] and fir waves[16] form for different reasons. Tiger bush consists of stripes of bushes on arid slopes in countries such as Niger where plant growth is limited by rainfall. Each roughly horizontal stripe of vegetation absorbs rainwater from the bare zone immediately above it.[15] In contrast, fir waves occur in forests on mountain slopes after wind disturbance, during regeneration. When trees fall, the trees that they had sheltered become exposed and are in turn more likely to be damaged, so gaps tend to expand downwind. Meanwhile, on the windward side, young trees grow, protected by the wind shadow of the remaining tall trees.[16]

Chemistry[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2013) |

Physics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2013) |

Bénard cells, Laser, cloud formations in stripes or rolls. Ripples in icicles. Washboard patterns on dirtroads. Dendrites in solidification, liquid crystals. Solitons.

Mathematics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2013) |

Sphere packings and coverings. Mathematics underlies the other pattern formation mechanisms listed.

Computer graphics[edit]

Some types of automata have been used to generate organic-looking textures for more realistic shading of 3d objects.[17][18]

A popular Photoshop plugin, KPT 6, included a filter called 'KPT reaction'. Reaction produced reaction-diffusion style patterns based on the supplied seed image.

A similar effect to the 'KPT reaction' can be achieved with convolution functions in digital image processing, with a little patience, by repeatedly sharpening and blurring an image in a graphics editor. If other filters are used, such as emboss or edge detection, different types of effects can be achieved.

Computers are often used to simulate the biological, physical or chemical processes that lead to pattern formation, and they can display the results in a realistic way. Calculations using models like Reaction-diffusion or MClone are based on the actual mathematical equations designed by the scientists to model the studied phenomena.

References[edit]

- ^ Ball, 2009.

- ^ Ball, 2009. Shapes, pp. 231–252.

- ^ Ball, 2009. Shapes, pp. 261–290.

- ^ Eric C. Lai (March 2004). "Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate" (PDF). Development. 131 (5): 965–73. doi:10.1242/dev.01074. PMID 14973298.

- ^ Melinda J. Tyler, David A. Cameron (2007). "Cellular pattern formation during retinal regeneration: A role for homotypic control of cell fate acquisition". Vision Research. 47 (4): 501–511. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2006.08.025. PMID 17034830.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Hans Meinhard (2001-10-26). "Biological pattern formation: How cell[s] talk with each other to achieve reproducible pattern formation". Max-Planck-Institut für Entwicklungsbiologie, Tübingen, Germany.

- ^ Wolpert L (October 1969). "Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation". J. Theor. Biol. 25 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(69)80016-0. PMID 4390734.

- ^ Wolpert, Lewis; et al. (2007). Principles of development (3rd ed.). Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927536-X.

- ^ Hall, B. K. (2003). "Evo-Devo: evolutionary developmental mechanisms". International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8): 491–495. PMID 14756324.

- ^ S. Kondo, T. Miura, "Reaction-Diffusion Model as a Framework for Understanding Biological Pattern Formation", Science 24 Sep 2010: Vol. 329, Issue 5999, pp. 1616-1620 DOI: 10.1126/science.1179047

- ^ Mercker et al. Biology Direct (2016) 11:22 DOI 10.1186/s13062-016-0124-7

- ^ Tallinen et al. Nature Physics 12, 588–593 (2016) doi:10.1038/nphys3632

- ^ Ball, 2009. Branches, pp. 52–59.

- ^ Ball, 2009. Shapes, pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b Tongway, D.J., Valentin, C. & Seghieri, J. (2001). Banded vegetation patterning in arid and semiarid environments. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1461265597.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b D'Avanzo, C. (22 February 2004). "Fir Waves: Regeneration in New England Conifer Forests". TIEE. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Greg Turk, Reaction-Diffusion

- ^ Andrew Witkin; Michael Kassy (1991). "Reaction-Diffusion Textures" (PDF). Proceedings of the 18th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques. pp. 299–308. doi:10.1145/122718.122750.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ball, Philip (2009). Nature's Patterns: a tapestry in three parts. 1:Shapes. 2:Flow. 3:Branches. Oxford. ISBN 978-0199604869.

External links[edit]

- SpiralZoom.com, an educational website about the science of pattern formation, spirals in nature, and spirals in the mythic imagination.

- '15-line Matlab code', A simple 15-line Matlab program to simulate 2D pattern formation for reaction-diffusion model.

.jpg/80px-Yemen_Chameleon_(cropped).jpg)