Viable system theory

Viable system theory (VST) concerns cybernetic processes in relation to the development/evolution of dynamical systems. They are considered to be living systems in the sense that they are complex and adaptive, can learn, and are capable of maintaining an autonomous existence, at least within the confines of their constraints. These attributes involve the maintenance of internal stability through adaptation to changing environments. One can distinguish between two strands such theory: formal systems and principally non-formal system. Formal viable system theory is normally referred to as viability theory, and provides a mathematical approach to explore the dynamics of complex systems set within the context of control theory. In contrast, principally non-formal viable system theory is concerned with descriptive approaches to the study of viability through the processes of control and communication, though these theories may have mathematical descriptions associated with them.

Contents

History[edit]

The concept of viability arose with Stafford Beer in the 1950s through his paradigm of management systems.[1][2][3] Its formal relative, viability theory began its life in 1976 with the mathematical interpretation of a book by Jacques Monod published in 1971 and entitled Chance and Necessity, and which concerned processes of evolution.[4] Viability theory is concerned with dynamic adaptation of uncertain evolutionary systems to environments defined by constraints, the values of which determine the viability of the system. Both formal and non-formal approaches ultimately concern the structure and evolutionary dynamics of viability in complex systems.

An alternative non-formal paradigm arose in the late 1980s through the work of Eric Schwarz.,[5] which increases the dimensionality of Beer's paradigm [6][7]

Beer viable system theory[edit]

The viable system theory of Beer is most well known through his viable system model [8] and is concerned with viable organisations capable of evolving.[9] Through both internal and external analysis it is possible to identify the relationships and modes of behaviour that constitute viability. The model is underpinned by the realisation that organisations are complex, and recognising the existence of complexity is inherent to processes of analysis. Beer's management systems paradigm is underpinned by a set of proposition, sometimes referred to as cybernetic laws. Siting within this is his viable systems model (VSM) and one of its laws is a principle of recursion, so that just as the model can be applied to divisions in a department, it can also be applied to the departments themselves. This is permitted through Beer's viability law which states that every viable system contains and is contained in a viable system.[10] The cybernetic laws are applied to all types of human activity systems[11] like organisations and institutions.

Now, paradigms are concerned with not only theory but also modes of behaviour within inquiry. One significant part of Beer's paradigm is the development of his Viable Systems Model (VSM) that addresses problem situations in terms of control and communication processes, seeking to ensure system viability within the object of attention. Another is Beer's Syntegrity protocol which centres on the means by which effective communications in complex situations can occur. VSM has been used successfully to diagnose organisational pathologies (conditions of social ill-health). The model involves not only an operative system that has both structure (e.g., divisions in an organisation or departments in a division) from which behaviour emanates that is directed towards an environment, but also a meta-system, which some have called the observer of the system.[12] The system and meta-system are ontologically different, so that for instance where in a production company the system is concerned with production processes and their immediate management, the meta-system is more concerned with the management of the production system as a whole. The connection between the system and meta-system is explained through Beer's Cybernetic map.[13] Beer considered that viable social systems should be seen as living systems.[14] Humberto Maturana used the term or autopoiesis (self-production) to explain biological living systems, but was reluctant to accept that social systems were living.

Schwarz viable system theory[edit]

The viable system theory of Schwarz is more directed towards the explicit examination of issues of complexity than is that of Beer. The theory begins with the idea of dissipative systems. While all isolated systems conserve energy, in non-isolated systems, one can distinguish between conservative systems (in which the kinetic energy is conserved) and dissipative systems (where the total kinetic and potential energy is conserved, but where part of the energy is changed in form and lost). If dissipated systems are far from equilibrium they "try" to recover equilibrium so quickly that they form dissipative structures to accelerate the process. Dissipative systems can create structured spots where entropy locally decreases and so negentropy locally increases to generate order and organisation. Dissipative systems involve far-from-equilibrium process that are inherently dynamically unstable, though they survive through the creation of order that is beyond the thresholds of instability.

Schwarz explicitly defined the living system in terms of its metastructure[15] involving a system, a metasystem and a meta-meta-system, this latter being an essential attribute. As with Beer, the system is concerned with operative attributes. Schwarz's meta-system is essentially concerned with relationships, and the meta-meta system is concerned with all forms of knowledge and its acquisition. Thus, where in Beer's theory learning processes can only be discussed in terms of implicit processes, in Schwarz's theory they can be discussed in explicit terms.

Schwarz's living system model is a summary of much of the knowledge of complex adaptive systems, but succinctly compressed as a graphical generic metamodel. It is this capacity of compression that establishes it as a new theoretical structure that is beyond the concept of autopoiesis/self-production proposed by Humberto Maturana, through the concept of autogenesis. While the concept of autogenesis has not had the collective coherence that autopoiesis has,[16][17] Schwarz clearly defined it as a network of self-creation processes and firmly integrated it with relevant theory in complexity in a way not previously done. The outcome illustrates how a complex and adaptive viable system is able to survive - maintaining an autonomous durable existence within the confines of its own constraints. The nature of viable systems is that they should have at least potential independence in their processes of regulation, organisation, production, and cognition. The generic model provides a holistic relationship between the attributes that explains the nature of viable systems and how they survive. It addresses the emergence and possible evolution of organisations towards complexity and autonomy intended to refer to any domain of system (e.g., biological, social, or cognitive).

Systems in general, but also human activity systems, are able to survive (in other words they become viable) when they develop:

(a) patterns of self-organisation that lead to self-organisation through morphogenesis and complexity;

(b) patterns for long term evolution towards autonomy;

(c) patterns that lead to the functioning of viable systems.

This theory was intended to embrace the dynamics of dissipative systems using three planes.

- Plane of energy.

- Plane of information.

- Plane of totality.

Each of the three planes (illustrated in Figure 1 below) is an independent ontological domain, interactively connected through networks of processes, and it shows the basic ontological structure of the viable system.

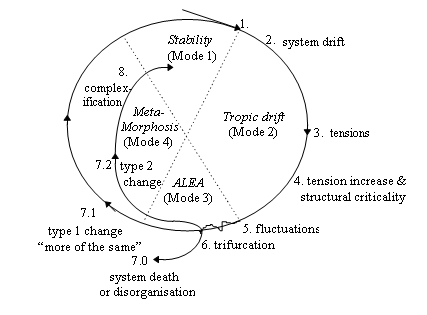

Connected with this is an evolutionary spiral of self-organisation (adapted from Schwarz's 1997 paper), shown in Figure 2 below.

Here, there are 4 phases or modes that a viable system can pass through. Mode 3 occurs with one of three possible outcomes (trifurcation): system death when viability is lost; more of the same; and metamorphosis when the viable system survives because it changes form.

The dynamic process that viable living systems have, as they move from stability to instability and back again, is explained in Table 1, referring to aspects of both Figures 1 and 2.

| Step | Movement toward evolution |

|---|---|

| 1. Stability | The system starts in a non-isolated condition, with some degree of stability. |

| 2. Tropic drift | Dissipative processes increase and the system is in danger of losing any robustness that it has. In complex systems the tropic drift enables potentials to be actualised. The drift takes the system away from its stable position and gives rise to tensions between the system and its parts and/or between the system and its environment. |

| 3. ALEA (crisis) | The tensions, following the tropic drift that moved the system away from its stable domain, lead the system to a non-linear condition of structural criticality. If the system loses robustness, fluctuations are amplified. |

| 4. Metamorphosis | Morphogenic change is induced through amplification. This occurs through differentiation. While the steps 103 above occur in the event plane, here more relational processes appear in the system through positive and negative feedback, and integration. |

| 5. Omeostasis | This slows down the morphogenesis of step 4, through the appearance of new integrative functional negative feedback loops. However, an unsuccessful result may produce regression, chaos, or destruction. |

| 6. Information drift and complexification | The above steps can be iterated increasing the complexity of the system. This is represented in the logical plane. |

| 7. Appearance of self-production cycles | When complexity reaches a very high level, a new kind of super-circularity can emerge: autopoiesis. This operates at the logical level of the system reinforcing the network of production. |

| 8. Autopoiesis | Complexification can continue in a safer way than in step 6. This is because there is an additional super-logical relation between the events that represent the system and its logical organisation. When this has happened, the system has increased its autonomy from the homeostatic steps of 5 and 6, to self-production. |

| 9. Self-reference | Increase in autonomy and development of individual identity occurs with self-reference in the logical plane. In stapes 5 and 6, the system could compensate for the unexpected variations in the environment through multiple homeostatic loops (steps 5 and 6). In steps 7 and 8 it developed the ability to increase its autonomy and complexification. Here it develops the ability to self-identify and dialogue with itself about matters that include its environment. |

| 10. Self-referential drift | This represents an intensification of self-reference. This is accompanied by an increase in the qualitative and quantitative dialogue between the system and its image within the system. This increases autonomy, and elevates the level of consciousness in a living system. It therefore solidifies individual identity. |

| 11. Autogenesis | This represents the self-production of the rules of production. It occurs in the existential plane. It defines the state of full autonomy, and is closed operationally. It defines being. |

Schwarz's VST has been further developed, set within a social knowledge context, and formulated as autonomous agency theory.[18][19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Introduction to management cybernetics. Cwarel Isaf Institute. http://www.kybernetik.ch/en/fs_intromankyb.html

- ^ Stafford Beer, 1959, Cybernetics and Management, English University Press http://www.toolshero.com/change-management/management-cybernetics)

- ^ Stafford Beer, (1966), Decision and Control: The Meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics, John Wiley & Sons, UK

- ^ Aubin, J. P., Bayen, A. M., & Saint-Pierre, P. (2011). Viability theory: new directions. Springer Science & Business Media

- ^ Schwarz, E., Aragno, M., Beck, H., Matthey, W., Remane, J., Chiffelle, F., Gern, J.P., Dubied, P.L., Bühle, P. (1988). La révolution des systems: une introduction à l'approche systémique: conférences interfacultaires données à l'Université de Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Cousset: Secrétariat de l'Université, DelVal

- ^ Schwarz, E. (1992) A Generic Model for the Emergence and Evolution of Natural Systems toward Complexity and Autonomy.Proceedings of the 36th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Systems Science,Denver, Vol. II

- ^ Schwarz, E. (1997). Toward a holistic cybernetics: from science through epistemology to being. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 4, 17-50

- ^ The Basis for the Viable System Model, The Intellingence Organization Conference, Monterrey, Mexico 1990. Chapter 3 video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BaLHocBdG3A

- ^ The theory of practice Cwarel Isaf Institute. http://www.kybernetik.ch/en/fs_methmod3.html

- ^ Beer, S. (1959) Cybernetics and Management. English U. Press, London.

- ^ Banathy, B. (2016) A Taste of systemics 29/09/2016 www.isss.org/primer/bela6.html

- ^ Von Foerster, H. (2003). Cybernetics of cybernetics. In Understanding understanding (pp. 283-286). Springer New York

- ^ Livas, J. The Cybernetic State. The Unity of Economics, Law and Politics. http://www.ototsky.mgn.ru/it/papers/JavierLivas_The-Cybernetic-State.pdf

- ^ Beer, S. (1980), Preface to Autopoiesis: The Organization of the Living, by Maturana, H., Varela, F.J., Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 42

- ^ St. Lawrence University Global Glossary: Metastructure http://it.stlawu.edu/~global/glossary/metastructure.html

- ^ Csányi, V. and Kampis, G. (1985), Autogenesis: the evolution of replicative systems, J. Theor. Biol., Vol. 114, pp. 303-323

- ^ Drazin and Sandlelands, (1992) Autogenesis. Organization Science http://webuser.bus.umich.edu/lsandel/PDFs/Autogenesis.pdf

- ^ Yolles, M. (2006). Organizations as Complex Systems: an introduction to knowledge cybernetics. Greenwich, CT, USA: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- ^ Guo, K,J.,; Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G.; Iles, P. (2016). The Changing Organisation: an Agency Approach. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.