Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston | |

|---|---|

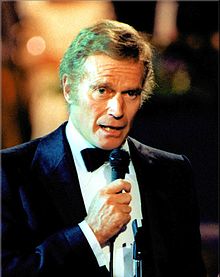

Heston in 1981 | |

| Born | John Charles Carter[1] October 4, 1923 Wilmette, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | April 5, 2008 (aged 84) |

| Resting place | Saint Matthew's Episcopal Church Columbarium Pacific Palisades, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Northwestern University |

| Occupation | Actor, activist |

| Years active | 1941–2003 |

| Home town | St. Helen, Michigan, U.S. Winnetka, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (after 1972) Democratic (before 1972) |

| Spouse(s) | Lydia Clarke (m. 1944) |

| Children | Fraser Clarke Heston, Holly Rochell Heston |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1944–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 77th Bombardment Squadron |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| President of the Screen Actors Guild | |

| In office 1965–1971 | |

| Preceded by | Dana Andrews |

| Succeeded by | John Gavin |

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter;[1] October 4, 1923 – April 5, 2008)[1][2] was an American actor and political activist.[3]

As a Hollywood star, he appeared in almost 100 films over the course of 60 years. He played Moses in the epic film The Ten Commandments (1956), for which he received his first nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama.[4] He also starred in Touch of Evil (1958) with Orson Welles, Ben-Hur (1959), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor, El Cid (1961), Planet of the Apes (1968), The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), Secret of the Incas (1954), The Big Country (1958) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).[5]

A supporter of Democratic politicians and civil rights in the 1960s, Heston later became a Republican, founding a conservative political action committee and supporting Ronald Reagan. Heston was the five-term president of the National Rifle Association (NRA), from 1998 to 2003. After being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2002, he retired from both acting and the NRA presidency.[6]

Contents

Early years[edit]

Charlton Heston was born John Charles Carter[1] on October 4, 1923, to Lilla (née Charlton Baines; 1899–1994) and Russell Whitford Carter (1897–1966), a sawmill operator.[7][8] Many sources indicate he was born in Evanston, Illinois.[9][10][11] Heston's autobiography,[12] however stated otherwise. Yet other sources place his birth in No Man's Land, Illinois, which usually refers to a then-unincorporated area now part of Wilmette, a wealthy Chicago suburb.[citation needed]

Heston said in a 1995 interview that he was not very good at remembering addresses or his early childhood.[13] Heston was partially of Scottish descent, including from the Clan Fraser, but the majority of his ancestry was English. His earliest immigrant ancestors arrived in America from England in the 1600s.[14][15][16][17][18] His maternal great-grandparents, and namesakes, were Englishman William Charlton from Sunderland and Scotswoman Mary Drysdale Charlton. They emigrated to Canada, where his grandmother, Marian Emily Charlton, was born in 1872.[19]

In his autobiography, Heston refers to his father participating in his family's construction business. When Heston was an infant, his father's work moved the family to St. Helen, Michigan.[20] It was a rural, heavily forested part of the state, and Heston lived an isolated yet idyllic existence, spending much time hunting and fishing in the backwoods of the area.[12]

When Heston was 10 years old, his parents divorced after having three children. Shortly thereafter, his mother remarried and Charlton and his younger sister Lilla and brother Alan moved back to Wilmette. Heston (his and his siblings' new surname) attended New Trier High School.[21] He recalled living there:

All kids play pretend games, but I did it more than most. Even when we moved to Chicago, I was more or less a loner. We lived in a North Shore suburb, where I was a skinny hick from the woods, and all the other kids seemed to be rich and know about girls.[22]:xii

Contradictions on paper and in an interview surround when "Charlton" became Heston's first name. The 1930 United States Census record for Richfield, Michigan, in Roscommon County, shows his name as being Charlton J. Carter at age six. Later accounts and movie studio biographies say he was born John Charles Carter and his two siblings born Lila and Alan Carter but later in 67' Lila and Alan legalized their last name to Heston after their biological father Russell Whitford Carter passed. No documentation showing Charlton legally changed his name.[1]

Charlton was his maternal grandmother Marian's maiden name,[19] not his mother Lilla's. This is contrary to how 20th century references read and what Heston said. When Heston's maternal grandmother and his true maternal grandfather Charles Baines[23] separated or divorced in the early 1900s, Marian (née Charlton) Baines married William Henry Lawton in 1907.[24] Charlton Heston's mother, Lilla, and her sister May were adopted by their grandfather, and changed their last name to Charlton in order to distance themselves from their biological father, Mr. Baines who was a gambler and never around.[25][26] After the Carters divorced in 1933 and Lilla Carter married Chester Heston, Charlton, sister Lilla and brother Alan Carter became Heston although not legally adopted.[27] It was thus as Charlton Heston that he appeared in his first film with younger brother Alan Carter (small role), an adaptation of Henrik Ibsen's Peer Gynt (1941).[28] His nickname was always Chuck.

Heston was an Episcopalian, and has been described as "a spiritual man" with an "earthy flair," who "respected religious traditions" and "particularly enjoyed the historical aspects of the Christian faith."[29]

Career[edit]

Heston frequently recounted that while growing up in northern Michigan in a sparsely populated area, he often wandered in the forest, "acting" out characters from books he had read.[30] Later, in high school, he enrolled in New Trier's drama program, playing the lead role in the amateur silent 16 mm film adaptation of Peer Gynt, from the Ibsen play, by future film activist David Bradley released in 1941.

From the Winnetka Community Theatre (or the Winnetka Dramatist's Guild, as it was then known) in which he was active, he earned a drama scholarship to Northwestern University; among his acting teachers was Alvina Krause.[31][32] Several years later, Heston teamed up with Bradley to produce the first sound version of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, in which Heston played Mark Antony.[33]

World War II service[edit]

In 1944, Heston enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces. He served for two years as a radio operator and aerial gunner aboard a B-25 Mitchell medium bomber stationed in the Alaskan Aleutian Islands with the 77th Bombardment Squadron of the Eleventh Air Force.[34][35] He reached the rank of staff sergeant.

In March 1944 Heston married Northwestern University student Lydia Marie Clarke at Grace Methodist Church in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. That same year, he joined the military. After his rise to fame, Heston narrated for highly classified military and Department of Energy instructional films, particularly relating to nuclear weapons, and "for six years Heston [held] the nation's highest security clearance" or Q clearance." The Q clearance is similar to a DoD or DIA clearance of top secret.[36]

New York[edit]

After the war, the Hestons lived in Hell's Kitchen, New York City, where they worked as artists' models. Seeking a way to make it in theatre, they decided to manage a playhouse in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1947, making $100 a week.

In 1948, they returned to New York, where Heston was offered a supporting role in a Broadway revival of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, starring Katharine Cornell. In television, Heston played a number of roles in CBS's Studio One, one of the most popular anthology dramas of the 1950s.

In 1949 Heston played Marc Antony in a televised production of Julius Caesar (1950).

Film producer Hal B. Wallis of Casablanca spotted Heston in a 1950 television production of Wuthering Heights and offered him a contract. When his wife reminded Heston they had decided to pursue theater and television, he replied, "Well, maybe just for one film to see what it's like."

Hollywood[edit]

Heston's first professional movie appearance was the leading role at age 26 in Dark City, a 1950 film noir produced by Hal Wallis. His breakthrough came when Cecil B. DeMille cast him as a circus manager in The Greatest Show on Earth, which was named by the Motion Picture Academy as the Best Picture of 1952. It was also the most popular movie of that year.

King Vidor used Heston in a melodrama with Jennifer Jones, Ruby Gentry (1952). He followed it with a Western at Paramount, The Savage (1952), playing a white man raised by Indians. 20th Century Fox used him to play Andrew Jackson in The President's Lady (1953) opposite Susan Hayward. Back at Paramount he was Buffalo Bill in Pony Express (1953). He followed this with another Western, Arrowhead (1953).

In 1953, Heston was Billy Wilder's first choice to play Sefton in Stalag 17. However, the role was given to William Holden, who won an Oscar for it. Hal Wallis reunited Heston with Lizabeth Scott in a melodrama Bad for Each Other (1953).

In 1954, he made two adventure films for Paramount. The Naked Jungle had him battle a plague of killer ants. He played the lead in Secret of the Incas, which was shot on location at the archeological site Machu Picchu and had numerous similarities to Raiders of the Lost Ark. Filmed a quarter-century before the latter film, "Incas" included a tomb scene with the revelatory shaft of light pointing out a clue on a map and featured Heston's roguish antiquities thief's costume and light beard; Raiders costume designer Deborah Nadoolman Landis noted that it was "almost a shot for shot similar" to the film on which she worked.[37]

Heston played William Clark, the explorer, in The Far Horizons (1955) alongside Fred MacMurray. He tried a comedy The Private War of Major Benson (1955) at Universal, then supported Jane Wyman in a drama Lucy Gallant (1955).

The Ten Commandments[edit]

Heston became an icon for playing Moses in the hugely successful biblical epic The Ten Commandments (1956), selected by director Cecil B. DeMille, who thought Heston bore an uncanny resemblance to Michelangelo's statue of Moses.[38] DeMille cast Heston's three-month-old son, Fraser Clarke Heston, as the infant Moses. The Ten Commandments became one of the greatest box office successes of all time and is the seventh highest-grossing film adjusted for inflation. His portrayal of the Hebrew prophet and deliverer was praised by film critics. The Hollywood Reporter described him as "splendid, handsome and princely (and human) in the scenes dealing with him as a young man, and majestic and terrible as his role demands it."[39] The New York Daily News wrote that he "is remarkably effective as both the young, princely Moses and as the Patriarchal savior of his people."[40] His performance as Moses earned him his first nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama and Spain's Fotogramas de Plata Award for Best Foreign Performer. The Egyptian Theater made its second debut in December 1998, with a screening of Cecil B. DeMille's 1923 original The Ten Commandments, which premiered at the Egyptian 75 years earlier. Charlton and Lydia Heston were honored guests and their longtime friends brothers Charles Elias Disney and Daniel H. Disney were seated with the Heston's for this opening showing in the Egyptian Theatre.

Heston went back to Westerns with Three Violent People (1957). Universal tried to interest him in a thriller starring Orson Welles, Touch of Evil; Heston agreed to be in it if Welles directed. The film has come to be regarded as a classic masterpiece. He also played a rare supporting role in William Wyler's The Big Country opposite Gregory Peck and Burl Ives.

Heston got another chance to play Andrew Jackson in The Buccaneer (1958), produced by De Mille and starring Yul Brynner.

Ben Hur[edit]

After Marlon Brando, Burt Lancaster, and Rock Hudson[41] turned down the title role in Ben-Hur (1959), Heston accepted the role, winning the Academy Award for Best Actor, one of the unprecedented 11 Oscars the film earned. After Moses and Ben-Hur, Heston became more identified with Biblical epics than any other actor. He later voiced Ben-Hur in an animated television production of the Lew Wallace novel in 2003.

Heston followed it with The Wreck of the Mary Deare (1959) co-starring Gary Cooper, which was a box office disappointment.

Heston turned down the lead opposite Marilyn Monroe in Let's Make Love to appear in Benn W. Levy's play The Tumbler, directed by Laurence Olivier.[42] Called a "harrowingly pretentious verse drama" by Time,[43] the production went through a troubled out-of-town tryout period in Boston and closed after five performances on Broadway in February 1960.[44] Heston, a great admirer of Olivier the actor, took on the play to work with him as a director. After the play flopped, Heston told columnist Joe Hyams, "I feel I am the only one who came out with a profit.... I got out of it precisely what I went in for – a chance to work with Olivier. I learned from him in six weeks things I never would have learned otherwise. I think I've ended up a better actor."[45]

Heston enjoyed acting on stage, believing it revivified him as an actor. He never returned to Broadway, but acted in regional theatres. His most frequent stage roles included the title role in Macbeth, and Mark Antony in both Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra.[citation needed] He played Sir Thomas More in A Man for All Seasons in several regional productions in the 1970s and 1980s, eventually playing it in London's West End. The play was a success and the West End production was taken to Aberdeen, Scotland, for a week, where it was staged at His Majesty's Theatre.[citation needed]

Samuel Bronston pursued Heston to play the title role in an epic shot in Spain, El Cid (1961), which was a big success. He was in a war film for Paramount, The Pigeon That Took Rome (1962), and a melodrama shot in Hawaii, Diamond Head (1963). Bronston wanted him for another epic and the result was 55 Days at Peking (1963), which was a box office disappointment.

Heston focused on epics: he was John the Baptist in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965); Michelangelo in The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) opposite Rex Harrison; the title role in Major Dundee (1965), directed by Sam Peckinpah. The War Lord (1965), directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, was on a smaller scale and critically acclaimed, though commercially it fared poorly. In Khartoum (1966) Heston played General Charles Gordon.

From 1965–71, Heston served as president of the Screen Actors Guild. The Guild had been created in 1933 for the benefit of actors, who had different interests from the producers and directors who controlled the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. He was more conservative than most actors, and publicly clashed with outspoken liberal actors such as Ed Asner.[46]

Counterpoint (1968) was a war film which was not particularly successful at the box office. Neither was the Western Will Penny (1968), directed by Tom Gries; however Heston received excellent reviews and it was one of his favorite films.

Planet of the Apes[edit]

Heston had not been in a big hit for a number of years but in 1968 he starred in Planet of the Apes, directed by Schaffner, which was hugely popular. Less so was a football drama, Number One (1969) directed by Gries. Heston had a smaller supporting role in Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), which was popular. However, The Hawaiians (1970), directed by Gries, was not.

In 1970, he portrayed Mark Antony again in another film version of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. His co-stars included Jason Robards as Brutus, Richard Chamberlain as Octavius, Robert Vaughn as Casca, and English actors Richard Johnson as Cassius, John Gielgud as Caesar, and Diana Rigg as Portia.

1970s action star[edit]

In 1971, he starred in the post-apocalyptic science-fiction film The Omega Man, which has received mixed critical reviews but was popular. He became a gun rights advocate.[47]

In 1972, Heston made his directorial debut and starred as Mark Antony in an adaptation of the William Shakespeare play he had performed earlier in his theater career, Antony and Cleopatra. Hildegarde Neil was Cleopatra and English actor Eric Porter was Ahenobarbus. After receiving scathing reviews, the film was never released to theaters, and is rarely seen on television. It was finally released on DVD in March 2011.[48]

His next film, Skyjacked (1972) was a hit.[49] However The Call of the Wild (1972) was a flop, one of Heston's least favorite films. He quickly recovered with a string of hits: Soylent Green (1973), another science fiction story; The Three Musketeers (1973), playing Cardinal Richelieu in an all-star cast; Earthquake (1974), a disaster film; Airport 1975 (1975), another disaster film; Midway (1976) a war film.

Heston's good run at the box office ended with Two-Minute Warning (1976), a disaster film, and The Last Hard Men (1976), a Western. He played King Henry VIII for The Prince and the Pauper (1977), from the Musketeers team, then starred in a disaster film, Gray Lady Down (1978).

Heston was in a Western written by his son, The Mountain Men (1980) and a horror film, The Awakening (1980). He made his second film as a director Mother Lode (1982) also written by his son; it was a commercial disappointment.

Later career[edit]

From 1985-87, he starred in his only prime time stint on a television series in the soap, The Colbys. With his son Fraser, he produced and starred in several TV movies, including remakes of Treasure Island and A Man For All Seasons. In 1992, Heston appeared on the A&E cable network in a short series of videos, Charlton Heston Presents the Bible, reading passages from the King James version.

Never taking himself too seriously, he also made a few appearances as "Chuck" in Dame Edna Everage's shows, both on stage and on television. Heston appeared in 1993 in a cameo role in Wayne's World 2, in a scene where Wayne Campbell (Mike Myers) requests casting a better actor for a small role. After the scene is reshot with Heston, Campbell weeps in awe. That same year, Heston hosted Saturday Night Live. He had cameos in the films Hamlet, Tombstone, and True Lies.

He starred in many theatre productions at the Los Angeles Music Center, where he appeared in Detective Story and The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, and as Sherlock Holmes in The Crucifer of Blood, opposite Richard Johnson as Dr. Watson. In 2001, he made a cameo appearance as an elderly, dying chimpanzee in Tim Burton's remake of Planet of the Apes. His last film role was as Josef Mengele in My Father, Rua Alguem 5555, which had limited release (mainly to festivals) in 2003.[50]

Heston's distinctive voice landed him roles as a film narrator, including Armageddon and Disney's Hercules. He played the title role in Mister Roberts three times and cited it as one of his favorite roles. In the early 1990s, he tried unsuccessfully to revive and direct the show with Tom Selleck in the title role.[51] In 1998, Heston had a cameo role playing himself in the American television series Friends, in the episode "The One with Joey's Dirty Day". In 2000, he played Chief Justice Haden Wainwright in The Outer Limits episode "Final Appeal".

Political activism[edit]

Heston's political activism had four stages.[52] In the first stage, 1955–61, he endorsed Democratic candidates for President, and signed on to petitions and liberal political causes. From 1961–72, the second stage, he continued to endorse Democratic candidates for President. Moving beyond Hollywood, he became nationally visible in 1963 in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. From 1965–71, he served as the elected president of the Screen Actors Guild, and clashed with his liberal rival Ed Asner. In 1968, he used his "cowboy" persona to publicize gun control measures.[citation needed]

The third stage began in 1972. Like many neoconservatives of the same era who moved from liberal Democrat to conservative Republican, he rejected the liberalism of George McGovern and supported Richard Nixon in 1972 for President. In the 1980s, he gave strong support to Ronald Reagan during his conservative presidency. In 1995, Heston entered his fourth stage by establishing his own political action fund-raising committee and jumped into the internal politics of the National Rifle Association. He gave numerous culture wars speeches and interviews upholding the conservative position, blaming media and academia for imposing affirmative action, which he saw as unfair reverse discrimination.[53]

Heston campaigned for Presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson in 1956, although he was unable to campaign for John F. Kennedy in 1960 due to filming on El Cid in Spain.[54] Reportedly, when in 1961 a segregated Oklahoma movie theater was showing his movie El Cid for the first time, he joined a picket line outside.[55] Heston made no reference to this in his autobiography but describes traveling to Oklahoma City to picket segregated restaurants, to the chagrin of the producers of El Cid, Allied Artists.[56] During the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom held in Washington, DC, in 1963, he accompanied Martin Luther King, Jr. In later speeches, he said he helped the civil rights cause "long before Hollywood found it fashionable."[57]

In the 1964 election, he endorsed Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had masterminded the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through Congress over the vociferous opposition of Southern Democrats. That year, Heston publicly opposed California Proposition 14 that rolled back the state's fair housing law, the Rumford Fair Housing Act.[citation needed]

In his 1995 autobiography, In the Arena, written after he became a conservative Republican, Heston wrote that while driving back from the set of The War Lord, he saw a "Barry Goldwater for President" billboard with his campaign slogan "In Your Heart You Know He's Right" and thought to himself, "Son of a bitch, he is right."[58] Heston later said that his support for Goldwater was the event that helped turn him against gun control laws.[59] Following the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, Heston, Gregory Peck, Kirk Douglas, and James Stewart issued a statement in support of President Johnson's Gun Control Act of 1968.[60][61] The Johnson White House had solicited Heston's support.[62] He endorsed Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 Presidential election.[63]

Heston opposed the Vietnam War during its course (though he changed his opinion in the years following the war)[64] and in 1969 was approached by the Democratic Party to run for the U.S. Senate against incumbent George Murphy. He agonized over the decision but ultimately determined he could never give up acting.[65] He is reported to have voted for Richard Nixon in 1972, though Nixon is not mentioned in his autobiography.[66]

By the 1980s, Heston supported gun rights and changed his political affiliation from Democratic to Republican. When asked why he changed political alliances, Heston replied "I didn't change. The Democratic Party changed."[67] In 1987, he first registered as a Republican.[68] He campaigned for Republicans and Republican Presidents Ronald Reagan,[69] George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush.[70]

Heston resigned in protest from Actors Equity, saying the union's refusal to allow a white actor to play a Eurasian role in Miss Saigon was "obscenely racist".[71][72]

Heston charged that CNN's telecasts from Baghdad were "sowing doubts" about the allied effort in the 1990–91 Gulf War."[41]

At a Time Warner stockholders' meeting, Heston castigated the company for releasing an Ice-T album which included a song "Cop Killer" about killing police officers. While filming The Savage, Heston was initiated by blood into the Miniconjou Lakota Nation, saying that he had no natural American Indian heritage, but elected to be "Native American" to salvage the term from exclusively referring to American Indians.[12]

In 1993, Heston teamed up with John Anthony West and Robert M. Schoch in an Emmy Award-winning NBC special, The Mystery of the Sphinx. West and Schoch had proposed a much earlier date for the construction of the Great Sphinx than generally accepted. They had suggested that the main type of weathering evident on the Great Sphinx and surrounding enclosure walls could only have been caused by prolonged and extensive rainfall and that the whole structure was carved out of limestone bedrock by an ancient advanced culture (such as the Heavy Neolithic Qaraoun culture).[73]

In a 1997 speech called "Fighting the Culture War in America", Heston rhetorically deplored a culture war he said was being conducted by a generation of media people, educators, entertainers, and politicians against:

... the God fearing, law-abiding, Caucasian, middle-class Protestant – or even worse, evangelical Christian, Midwestern or Southern – or even worse, rural, apparently straight – or even worse, admitted heterosexuals, gun owning – or even worse, NRA-card-carrying, average working stiff – or even worse, male working stiff – because, not only don't you count, you are a down-right obstacle to social progress. Your voice deserves a lower decibel level, your opinion is less enlightened, your media access is insignificant; and frankly, mister, you need to wake up, wise up, and learn a little something from your new America; and until you do, would you mind shutting up?[74]

He went on to say:

The Constitution was handed down to guide us by a bunch of wise old dead white guys who invented our country! Now some flinch when I say that. Why! It's true-they were white guys! So were most of the guys that died in Lincoln's name opposing slavery in the 1860s. So why should I be ashamed of white guys? Why is "Hispanic Pride" or "Black Pride" a good thing, while "White Pride" conjures shaven heads and white hoods? Why was the Million Man March on Washington celebrated by many as progress, while the Promise Keepers March on Washington was greeted with suspicion and ridicule? I'll tell you why: Cultural warfare!

In an address to students at Harvard Law School entitled "Winning the Cultural War", Heston said, "If Americans believed in political correctness, we'd still be King George's boys – subjects bound to the British crown."[75]

He said to the students:

You are the best and the brightest. You, here in this fertile cradle of American academia, here in the castle of learning on the Charles River. You are the cream. But I submit that you and your counterparts across the land are the most socially conformed and politically silenced generation since Concord Bridge. And as long as you validate that and abide it, you are, by your grandfathers' standards, cowards.[75]

During a speech at Brandeis University, he stated, "Political correctness is tyranny with manners".[76] In a speech to the National Press Club in 1997, Heston said, "Now, I doubt any of you would prefer a rolled up newspaper as a weapon against a dictator or a criminal intruder."[77]

Heston was the president (a largely ceremonial position) and spokesman of the NRA from 1998 until he resigned in 2003. At the 2000 NRA convention, he raised a rifle over his head and declared that a potential Al Gore administration would take away his Second Amendment rights "from my cold, dead hands".[78][79] In announcing his resignation in 2003, he again raised a rifle over his head, repeating the five famous words of his 2000 speech. Heston became an honorary life member.[80]

In the 2002 film Bowling for Columbine, Michael Moore interviewed Heston at Heston's home, asking him about an April 1999 meeting the NRA held in Denver, Colorado, shortly after the Columbine high school massacre. Moore criticized Heston for the perceived thoughtlessness in the timing and location of the meeting. When Moore asked Heston for his thoughts on why gun-related homicide is so much higher in the United States than in other countries, Heston said it was because, "we have probably more mixed ethnicity" and/or that "we have a history of violence, perhaps more than most countries."[81] Heston subsequently, on-camera, excused himself and walked away. Moore was later criticized for having conducted the interview in what some viewed as an ambush.[82][83][84] The interview was conducted early in 2001, before Heston publicly announced his Alzheimer's diagnosis, but the film was released afterward, causing some to say that Moore should have cut the interview from the final film.[85]

In April 2003, he sent a message of support to the American forces in the Iraq War, attacking opponents of the war as "pretend patriots".[86]

Heston opposed abortion and introduced Bernard Nathanson's 1987 pro-life documentary, Eclipse of Reason, which focuses on late-term abortions. Heston served on the advisory board of Accuracy in Media, a conservative media watchdog group founded by Reed Irvine.[87]

Illness and death[edit]

In 1996, Heston had a hip replacement. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1998. Following a course of radiation treatment, the cancer went into remission. In 2000, he publicly disclosed that he had been treated for alcoholism at a Utah clinic in May–June of that year.[88]

On August 9, 2002, he publicly announced (via a taped message) that he had been diagnosed with symptoms consistent with Alzheimer's disease.[89] In July 2003, in his final public appearance, Heston received the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House from President George W. Bush. In March 2005, various newspapers reported that family and friends were shocked by the progression of his illness, and that he was sometimes unable to get out of bed.[90]

Heston died on the morning of April 5, 2008, at his home in Beverly Hills, California, with Lydia, his wife of 64 years, by his side. He was also survived by their son, Fraser Clarke Heston, and adopted daughter, Holly Ann Heston. The cause of death was not disclosed by the family.[91][92] A month later, media outlets reported his death was due to pneumonia.[93]

Early tributes came in from leading figures; President George W. Bush called Heston "a man of character and integrity, with a big heart ... He served his country during World War II, marched in the civil rights movement, led a labor union and vigorously defended Americans' Second Amendment rights." Former First Lady Nancy Reagan said that she was "heartbroken" over Heston's death and released a statement, reading, "I will never forget Chuck as a hero on the big screen in the roles he played, but more importantly I considered him a hero in life for the many times that he stepped up to support Ronnie in whatever he was doing."[94]

Heston's funeral was held a week later on April 12, 2008, in a ceremony which was attended by 250 people including Nancy Reagan and Hollywood stars such as California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, Olivia de Havilland, Keith Carradine, Pat Boone, Tom Selleck, Oliver Stone (who had cast Heston in his 1999 movie Any Given Sunday), Rob Reiner, and Christian Bale.[95][96][97]

The funeral was held at Episcopal Parish of St. Matthew's Church in Pacific Palisades, the church where Heston had regularly worshipped and attended Sunday services since the early 1980s.[98][99] He was cremated and his ashes were given to his family.[100]

Legacy[edit]

.jpg/220px-Charlton_Heston_(handprints_in_cement).jpg)

Richard Corliss wrote in Time magazine, "From start to finish, Heston was a grand, ornery anachronism, the sinewy symbol of a time when Hollywood took itself seriously, when heroes came from history books, not comic books. Epics like Ben-Hur or El Cid simply couldn't be made today, in part because popular culture has changed as much as political fashion. But mainly because there's no one remotely like Charlton Heston to infuse the form with his stature, fire, and guts."[101]

In his obituary for the actor, film critic Roger Ebert noted, "Heston made at least three movies that almost everybody eventually sees: Ben-Hur, The Ten Commandments and Planet of the Apes."[102]

Heston's cinematic legacy was the subject of Cinematic Atlas: The Triumphs of Charlton Heston, an 11-film retrospective by the Film Society of the Lincoln Center that was shown at the Walter Reade Theatre from August 29 to September 4, 2008.[103]

On April 17, 2010, Heston was inducted into the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum's Hall of Great Western Performers.[104]

In his childhood hometown of St. Helen, Michigan, a charter school, Charlton Heston Academy, opened on September 4, 2012. It is housed in the former St. Helen Elementary School. Enrollment on the first day was 220 students in grades kindergarten through eighth.[105]

Charlton Heston was commemorated on a United States postage stamp issued on April 11, 2014.[106]

Charlton Heston was inducted as a Laureate of the Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln (the State's highest honor) by the Governor of Illinois in 1977 in the area of Performing Arts.[107]

Accolades[edit]

Filmography[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

by Heston:

- In the Arena: An Autobiography (1997); ISBN 1-57297-267-X

- The Courage to be Free (2000), speeches ISBN 978-0-9703688-0-5

- The Actors Life: Journals 1956–1976 (1978); ISBN 0-671-83016-3

- Beijing Diary; ISBN 0-671-68706-9

- To Be a Man: Letters to My Grandson; ISBN 0-7432-1311-4

- Charlton Heston Presents the Bible; ISBN 1-57719-270-2

- Charlton Heston's Hollywood: 50 Years in American Film with Jean-Pierre Isbouts; ISBN 1-57719-357-1

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Eliot, Marc. Hollywood's Last Icon: Charlton Heston, HarperCollins Publishing © 2017; ISBN 978-0-06-242043-5 (553 pages); pp. 11-12 address birthname controversy: "Then, as if to erase everything that reminded her son of Russell, Lilla told him his name was no longer John Charles Carter; from now on he was Charlton Heston."

- ^ The 1930 United States Census; Richfield, Roscommon County, Michigan.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (April 6, 2008). "Charlton Heston, Epic Film Star and Voice of N.R.A., Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

Charlton Heston, who appeared in some 100 films in his 60-year acting career, but who is remembered especially chiefly for his monumental, jut-jawed portrayals of Moses, Ben-Hur and Michelangelo, died Saturday night at his home in Beverly Hills, California. He was 84.

- ^ "Charlton Heston". Golden Globe Awards Official Website. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Emilie Raymond, From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics, (2006), pp 4–5, 33

- ^ "Charlton Heston's Last Sneer", SFGate.com, April 30, 2003.

- ^ Biography, Filmreference.com; retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ The 1900 United States Census; Cook County, Chicago, Illinois, United States.

- ^ Werling, Karen (April 16, 2008). "Appreciation: Charlton Heston's life as a Wildcat". North by Northwestern. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (April 6, 2008). "Charlton Heston, Epic Film Star and Voice of N.R.A., Dies at 84". New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Charlton Heston Biography". biography.com. March 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c Heston, Charlton: In The Arena, Simon & Schuster, 1995; ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- ^ Schultz, Rick (1995). "Appreciation: Charlton Heston's Interview, Articles & Tribute". Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Hollywood legend Charlton Heston was proud of Scots roots". Daily Record. April 7, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Charlton Heston".

- ^ "Do not believe everything you see in films". The Argus.

- ^ "Park City Daily News - Google News Archive Search".

- ^ Notable Kin: An Anthology of Columns First Published in the Nehgs Nexus, 1986-1995 by Gary B. Roberts, David Curtis Dearborn, John Anderson Brayton, Richard E. Brenneman, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Carl Boyer, 1997 page 21

- ^ a b The 1880 United States Census; Chicago, Cook County, Illinois.

- ^ My Bay City article, February 5, 2006 Archived November 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Habermehl, Kris (January 25, 2007). "Fire Breaks Out At Prestigious High School". Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Heston, Charlton. The Actor's Life, E.P. Dutton, N.Y. (1976)

- ^ [The 1900 United States Census; Chicago, Cook County, Illinois]

- ^ [Cook County, Illinois Marriages Index, 1871 - 1920]

- ^ Cook County, Illinois Marriage Indexes, 1912-1942.

- ^ The 1920 United State Census; Chicago, Cook County, Illinois.

- ^ Raymond, Emile (2006), From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics, University of Kentucky Press, p. 321, ISBN 978-0813171494

- ^ Staff (1999). AFI Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States. University of California Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0520215214. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Raymond, Emilie (2006-08-18). From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813171494.

- ^ Private Screenings: Charlton Heston (1998). Tcm.com; retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ "New Theater Honors Alvina Krause". Northwestern (magazine). Spring 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Goode, James (December 15, 2004). "Ms. Alvina Krause". Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved December 2, 2013. Please see also www

.bte .org /alvina-krause - ^ Brode, Douglas (April 27, 2000). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Shakespeare in Love. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-199-72802-2. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Mecca, Pete (December 10, 2013). "During World War II, Hollywood got serious". Covnews.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ "Heston tribute to airmen". The Independent. 1997-08-02. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ^ "Top Secret". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Mike French & Gilles Verschuere (September 14, 2005). "Debora Nadoolman interview". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Orrison, Katherine (1999). Written in Stone: Making Cecil B. DeMille's Epic The Ten Commandments. Vestal Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1461734819.

- ^ "'The Ten Commandments': Read THR's 1956 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. October 5, 1956. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Flashback: Original 1956 review of 'The Ten Commandments' in the Daily News". New York Daily News. November 9, 1956. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (April 6, 2008). "Film Legend Charlton Heston Dead at 84". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008.

- ^ Rovin, Jeff (1977). The Films of Charlton Heston. New York: Lyle Stuart. p. 224. ISBN 978-0806505619.

- ^ "The Theater: New Plays on Broadway". Time Magazine. March 7, 1960. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "The Tumbler". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Hyams, Joe (March 3, 1960). "Heston Not Hurt By Flop Play". Toledo Blade. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Emilie Raymond, "The Agony and the Ecstasy: Charlton Heston and the Screen Actors Guild", Journal of Policy History (2005) 17#2, pp 217–39.

- ^ "The Omega Man". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Antony & Cleopatra: Movies & TV. Amazon.com. Retrieved on November 14, 2011.

- ^ Soares, Emily. "Skyjacked (1972)". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies (TCM). Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Variety, February 12, 2004.

- ^ Heston, Charlton: In The Arena, Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 479; ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- ^ Raymond, From My Cold, Dead Hands, pp 5–7

- ^ Steven J. Ross, Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics (2011), Chapter 7. 978-0-19-518172-2

- ^ Mathews, Jay (May 2, 1986). "Charlton Heston, Statesman On the Set; For the 'Colbys' Star, Acting Is Only Part of the Job". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- ^ Taylor, Quintard (1998). In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-393-31889-0.

- ^ Heston, Charlton (1995). In The Arena. Simon & Schuster. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-684-80394-4.

- ^ Goodrich, Terry Lee (February 13, 2000). "Heston decries political correctness at fund-raiser". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. p. 5.

- ^ Ross, Steven J. (2011). Hollywood Left and Right:How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press USA. p. 288. ISBN 978-0195181722.

- ^ Denning, Brandon P. (2012). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313386701.

- ^ David Plotz. NRA President Charlton Heston, slate.com; accessed July 1, 2015.

- ^ Charlton Heston, Gun-Controller!, slate.com; accessed July 1, 2015.

- ^ Ross, Steven J. Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics.

- ^ Raymond, Emilie (2006). From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 5. ISBN 978-0813124087.

- ^ Heston, Charlton: In The Arena, Simon & Schuster, 1995, pp. 381, 401–403. ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- ^ Heston, Charlton: In The Arena, Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 433; ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- ^ Pulera, Dominic J. (2006). Sharing the Dream: White Males in Multicultural America. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8264-1829-6.

- ^ Raymond, Emilie (2006). From My Cold, Dead Hands Charlton Heston and American Politics. University Press of Kentucky. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8131-2408-7.

- ^ Raymond. From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics. p. 1.

- ^ McDowell, Charles (September 14, 1997). "Charlton Heston, the Gun Lobbyist". Richmond Times Dispatch (Virginia). p. B1.

- ^ Raymond, p. 276.

- ^ Karen Shimakawa (2002). National Abjection: The Asian American Body Onstage. Duke University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0822328230.

- ^ Ross, Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics (2011), p. 307

- ^ Schoch, Robert M. (1992). "Redating the Great Sphinx of Giza" Archived February 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine in Circular Times (ed. Collette M. Dowell); retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ [1] Charlton Heston's Keynote Address at the Free Congress Foundation's 20th Anniversary Gala

- ^ a b Heston, Charlton. Winning the Cultural War, americanrhetoric.com, February 16, 1999.

- ^ "Heston Champions Second Amendment". CBS News. March 29, 2000.

- ^ Gold, Dudley Susan. Open For Debate: Gun Control. Benchmark Books. January 2004.

- ^ Raymond, From My Cold, Dead Hands, pp 5–7, 241, 257.

- ^ Variety, "Gore fires back after Heston tirade", June 13, 2000.

- ^ Johnson, Jeff (April 25, 2003). "Heston to Step down as NRA President". The Nation. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008.

- ^ Boyar, Jay (September 9, 2002). "Heston's remarks bring buzz to Moore's documentary". Orlando Sentinel.

- ^ Russo, Tom (August 24, 2003). "Opposites attract, Charlton Heston, Michael Moore are a provocative pair". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 18, 2004). "'9/11': Just the facts?". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 55. "In some cases, [Moore] was guilty of making a good story better, but in other cases (such as his ambush of Charlton Heston) he was unfair..."

- ^ Whitty, Stephen (April 6, 2008). "The best action hero". The Star-Ledger.

- ^ Staff (2008-04-06). "Screen Legend Charlton Heston Dead at 84". ABC News. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ^ "Heston's war cry for troops". BBC. April 11, 2003. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ "FAQ". Accuracy in Media. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ Charlton Heston 'feeling good' after alcohol rehab.

- ^ "Charlton Heston has Alzheimer's symptoms" Archived August 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, CNN News. August 9, 2002.

- ^ "Charlton Heston – Heston In Rapid Decline", Contactmusic.com, March 6, 2005; retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. and Susan King. Charlton Heston, 84; actor played epic figures., Los Angeles Times, April 5, 2008; retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Charlton Heston Dies at Beverly Hills Home, FoxNews.com, April 5, 2008; retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "Document: Pneumonia Caused The Death Of Charlton Heston". Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ Ayres, Chris (April 7, 2008). "Charlton Heston, a star who defied the Hollywood liberals, is dead". The Times Online. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Politicians, actors and relatives gather for funeral of Hollywood icon Charlton Heston, International Herald Tribune; retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "Stars attend Heston's LA funeral", BBC.co.uk; accessed April 13, 2008.

- ^ "Fraser Heston in conversation with James Byrne". Secret of the Incas web site. May 12, 2008. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Memorial to Mr. Charlton Heston". Charlton Heston World. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Bob Thomas (April 12, 2008). "Luminaries Attend Heston's Funeral". MSNBC. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ "Stars Attend Heston's LA Funeral". BBC. April 13, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (April 10, 2008). "Charlton Heston: The Epic Man", time.com; accessed December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Charlton Heston, Richard Widmark: Tough guys, strong presences". Chicago Sun-Times. April 10, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Cinematic Atlas: The Triumphs of Charlton Heston". Film Society of the Lincoln Center. Archived from the original on September 1, 2008. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ "Hall of Great Western Performers". National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ Charlton Heston Academy, charltonhestonacademy.com; retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Charlton Heston". USPSStamps.com. United States Postal Service. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ "Laureates by Year - The Lincoln Academy of Illinois".

Further reading[edit]

This section lacks ISBNs for the books listed in it. (April 2015) |

- Bernier, Michelle Bernier. Charlton Heston: An Incredible Life (2nd ed. 2009) excerpt and text search

- Raymond, Emilie. From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics (2006) excerpt and text search; biography by scholar focused on political roles

- Ross, Steven J. Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics (2011) ch 7 on Heston

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlton Heston. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charlton Heston |

- Charlton Heston at the Internet Broadway Database

- Charlton Heston on IMDb

- Charlton Heston at Find a Grave

- Reel Classics

- BBC News Obituary

- 'From Our Files: An Interview with Charlton Heston' by Phil Elderkin, The Christian Science Monitor, November 4, 1959.

- Charlton Heston papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Marion P. Hammer |

President of the National Rifle Association 1998–2003 |

Succeeded by Kayne Robinson |

- 1923 births

- 2008 deaths

- 20th-century American Episcopalians

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American Episcopalians

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male writers

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Activists from California

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American autobiographers

- American civil rights activists

- American gun rights advocates

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American army personnel of World War II

- American people of Canadian descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American television directors

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Broadway theatre people

- Burials in California

- California Democrats

- California Republicans

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- Clan Fraser

- David di Donatello winners

- Deaths from Alzheimer's disease

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Disease-related deaths in California

- Film directors from Illinois

- Film directors from Michigan

- Infectious disease deaths in California

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Illinois

- Male actors from Michigan

- New Trier High School alumni

- Northwestern University School of Communication alumni

- Paramount Pictures contract players

- People from Beverly Hills, California

- People from Roscommon County, Michigan

- People from Wilmette, Illinois

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Presidents of the National Rifle Association

- Presidents of the Screen Actors Guild

- United States Army Air Forces soldiers

- Writers from California

- Writers from Illinois

- Writers from Michigan

- Film directors from California

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American conservative people