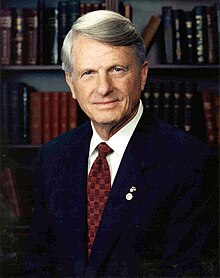

Zell Miller

Zell Miller | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Georgia | |

| In office July 24, 2000 – January 3, 2005 | |

| Appointed by | Roy Barnes |

| Preceded by | Paul Coverdell |

| Succeeded by | Johnny Isakson |

| 79th Governor of Georgia | |

| In office January 14, 1991 – January 11, 1999 | |

| Lieutenant | Pierre Howard |

| Preceded by | Joe Frank Harris |

| Succeeded by | Roy Barnes |

| 8th Lieutenant Governor of Georgia | |

| In office January 14, 1975 – January 14, 1991 | |

| Governor | George Busbee Joe Frank Harris |

| Preceded by | Lester Maddox |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Howard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Zell Bryan Miller February 24, 1932 Young Harris, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | March 23, 2018 (aged 86) Young Harris, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Shirley Carver (m. 1954) [1] |

| Children | 2[1] |

| Education | Young Harris College University of Georgia (BA, MA) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1953–1956 |

| Rank | |

Zell Bryan Miller (February 24, 1932 – March 23, 2018) was an American author and politician from the U.S. state of Georgia. A Democrat, Miller served as lieutenant governor from 1975 to 1991, 79th Governor of Georgia from 1991 to 1999, and as U.S. Senator from 2000 to 2005.

Miller was a conservative Democrat as a senator in the 2000s, after having been more liberal as governor in the 1990s. In 2004, he supported Republican President George W. Bush against Democratic nominee John Kerry in the presidential election. Miller was a keynote speaker at both major American political parties' national conventions—Democratic in 1992 and Republican in 2004.

He did not seek re-election to the Senate in 2004. After retiring from the Senate, he joined the law firm McKenna Long & Aldridge as a non-lawyer professional in the firm's national government affairs practice.[2] Miller was also a Fox News contributor.

Contents

Early life and military career[edit]

Miller was born in the small mountain town of Young Harris, Georgia. His father, Stephen Grady Miller (1891–1932),[3] was a teacher who died of cerebral meningitis[4] when Miller was a 17-day-old infant,[1] and the future politician was raised by his widowed mother, Birdie Bryan (1893–1980).[5][6] He had an elder sister, Jane, who was six years older than he.[1][4] As a child, Miller lived both in Young Harris and Atlanta. Miller received an associate degree from Young Harris College in his home town[7] and later attended Emory University.[1]

Less than a month after the Korean War armistice, Miller wound up in a drunk tank in the mountains of North Georgia. Miller stated later that this incident was the lowest point of his life.[8] Upon his release, Miller enlisted in the Marines. During his three years in the United States Marine Corps, Miller attained the rank of sergeant. He often referred to the value of his experience in the Marine Corps in his writing and stump speeches. In his book on the subject, entitled Corps Values: Everything You Need to Know I Learned in the Marines, he wrote:

In the twelve weeks of hell and transformation that were Marine Corps boot camp, I learned the values of achieving a successful life that have guided and sustained me on the course which, although sometimes checkered and detoured, I have followed ever since.[8]

After serving in the Marines, Miller enrolled in 1956[1] and earned bachelor's and master's degrees in history from the University of Georgia.[7] He taught history at Young Harris College following his graduation from the University of Georgia.[9]

Political career[edit]

Miller's parents were both involved in local politics in the North Georgia mountains. Miller, a Democrat, taught history and political science at Young Harris College,[1] before becoming mayor of Young Harris from 1959 to 1960, and was elected to two terms as a Georgia state senator from 1961 until 1964.[10] In 1964 and 1966, he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for the United States House of Representatives. He endorsed segregation in both races. He later served in state government as the executive secretary to Governor Lester Maddox[1] and in the Georgia Democratic Party, and was the Georgia state chairman for Walter Mondale's 1984 presidential campaign.[11]

Miller's first experience in the executive branch of government was as Chief of Staff for Georgia governor Lester Maddox. He was elected Lieutenant Governor of Georgia in 1974, serving four terms from 1975 to 1991, through the terms of Governors George Busbee and Joe Frank Harris, making him the longest-serving lieutenant governor in Georgia history. In 1980, Miller unsuccessfully challenged Herman Talmadge in the Democratic primary for his seat in the United States Senate.[12]

Governor[edit]

Miller was elected governor of Georgia in 1990, defeating Republican Johnny Isakson (who later became his successor as U.S. Senator) after defeating Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young and future Governor Roy Barnes in the primary.[12][13] Miller campaigned on the concept of term limits and pledged to seek only a single term as governor. He later ran for and won re-election in 1994.[14] James Carville was Miller's campaign manager.[15]

In 1991, Miller endorsed Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas for President of the United States.[16] Miller gave the keynote speech at the 1992 Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden in New York City.[16] In two oft-recalled lines, Miller said that President George H. W. Bush "just doesn't get it," and he remarked of a statement by Vice President Dan Quayle:

I know what Dan Quayle means when he says it's best for children to have two parents. You bet it is! And it would be nice for them to have trust funds, too. We can't all be born rich and handsome and lucky. And that's why we have a Democratic Party. My family would still be isolated and destitute if we had not had F.D.R.'s Democratic brand of government. I made it because Franklin Delano Roosevelt energized this nation. I made it because Harry Truman fought for working families like mine. I made it because John Kennedy's rising tide lifted even our tiny boat. I made it because Lyndon Johnson showed America that people who were born poor didn't have to die poor. And I made it because a man with whom I served in the Georgia Senate, a man named Jimmy Carter, brought honesty and decency and integrity to public service.[17]

As governor, Miller was a staunch promoter of public education. He helped found the HOPE Scholarship, which paid for the college tuition of Georgia students who both established a GPA of 3.0 in high school and maintained the same while in college, and who were from families earning less than $66,000 per year.[18] The HOPE Scholarships were funded by revenue collected from the state lottery. In December 1995, his office announced a proposal for $1 billion more in spending on education.[19] HOPE won praise from national Democratic leaders. The HOPE Scholarship program still to this day provides Georgia students with an opportunity to attend a public college or university, who otherwise may have no opportunity to do so.

Upon leaving the governor's office in January 1999, Miller accepted teaching positions at Young Harris College, Emory University, and the University of Georgia. He was a visiting professor at all three institutions when he was appointed to the U.S. Senate.[7]

Senate[edit]

Miller's successor as governor, Roy Barnes, appointed Miller to a U.S. Senate seat following the death of Republican Sen. Paul Coverdell in July 2000. While the Democratic Party's historic control of Georgia politics had waned for years, Miller remained popular. He defeated Mack Mattingly in a special election to keep the seat in November 2000.[9]

Miller often supported Republicans and criticized Democrats during his tenure in the Senate. He supported much of George W. Bush's agenda, including tax cuts and oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.[9] He supported pro-life policies as a senator, after supporting abortion rights as governor.[11] However, Miller remained a Democrat, saying, "I'll be a Democrat 'til the day I die."[20] Miller campaigned for fellow Georgia Democrat Max Cleland in his 2002 re-election campaign against Republican Congressman Saxby Chambliss, despite their ideological differences.[21]

Miller argued in his book A National Party No More: The Conscience of a Conservative Democrat (authored and published in 2003) that the Democratic Party lost its majority because it does not stand for the same ideals that it did in the era of John F. Kennedy. He argued that the Democratic Party, as it now stands, is a far left-wing party that is out of touch with the America of today and that the Republican Party now embraces the conservative Democratic ideals that he has held for so long. The book spent nine weeks in the New York Times Best Seller list for hardback non-fiction, rising to fourth position.[22]

In 2003, Miller announced that he would not seek re-election after completing his term in the Senate.[23] He also announced that he would support President George W. Bush in the 2004 presidential election rather than any of the nine candidates then competing for his own party's nomination.[24] Democratic Congresswoman Denise Majette sought to fill Miller's Senate seat, but lost the 2004 election to Republican Johnny Isakson.[25]

2004 election support for Republicans[edit]

In his keynote speech at the 2004 Republican National Convention, delivered on September 1, 2004, Miller criticized the state of the Democratic Party. He said, "No pair has been more wrong, more loudly, more often than the two senators from Massachusetts – Ted Kennedy and John Kerry." He also criticized John Kerry's Senate voting record, claiming that Kerry's votes against bills for defense and weapon systems indicated support for weakening U.S. military strength.

The B-1 bomber, that Senator Kerry opposed, dropped 40 percent of the bombs in the first six months of Enduring Freedom. The B-2 bomber, that Senator Kerry opposed, delivered air strikes against the Taliban in Afghanistan and Hussein's command post in Iraq. The F-14A Tomcats, that Senator Kerry opposed, shot down Khadafi's Libyan MiGs over the Gulf of Sidra. The modernized F-14D, that Senator Kerry opposed, delivered missile strikes against Tora Bora. The Apache helicopter, that Senator Kerry opposed, took out those Republican Guard tanks in Kuwait in the Gulf War. The F-15 Eagles, that Senator Kerry opposed, flew cover over our Nation's Capital and this very city after 9/11. I could go on and on and on: against the Patriot Missile that shot down Saddam Hussein's scud missiles over Israel; against the Aegis air-defense cruiser; against the Strategic Defense Initiative; against the Trident missile; against, against, against. This is the man who wants to be the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Armed Forces? U.S. forces armed with what? Spitballs?[26]

The speech was well received by the convention attendees, especially the Georgia delegates. Conservative commentator Michael Barone compared the speech to the views and ideology of Andrew Jackson.[27]

Miller's combative reaction to post-speech media interviews received almost as much attention as the speech itself. First, in an interview with CNN, Miller had a dispute with Judy Woodruff, Wolf Blitzer, and Jeff Greenfield when they questioned him on his speech, particularly on whether he had misinterpreted the context and full content of Kerry's votes, and the fact that Dick Cheney, as Defense Secretary, had opposed some of the same programs he attacked Kerry for voting against.[28]

Shortly thereafter, Miller appeared in an interview with Chris Matthews on the MSNBC show Hardball. After Miller expressed irritation at Matthews' line of questioning, Matthews pressed Miller with the question, "Do you believe now – do you believe, Senator, truthfully, that John Kerry wants to defend the country with spitballs?" Miller angrily told Matthews to "get out of my face," and declared, "I wish we lived in the day where you could challenge a person to a duel."[29] Miller later said about the interview, "That was terrible. I embarrassed myself. I'd rather it had not happened."[30]

After Bush won the election of 2004, Miller referred to the Republican victories in that election (including a sweep of five open Senate seats in the South) as a sign that Democrats did not relate to most Americans. Calling for Democrats to change their message, he authored a column, which appeared in the Washington Times on November 4, 2004, in which he wrote:

Fiscal responsibility is unbelievable in the face of massive new spending promises. A foreign policy based on the strength of 'allies' like France is unacceptable ... A strong national defense policy is just not believable coming from a candidate who built a career as an anti-war veteran, an anti-military candidate and an anti-action senator. ... When will national Democrats sober up and admit that that dog won't hunt? Secular socialism, heavy taxes, big spending, weak defense, limitless lawsuits and heavy regulation – that pack of beagles hasn't caught a rabbit in the South or Midwest in years.[31]

Post-2004 endorsements[edit]

Miller declared early in 2008 that he would not support either Senator Barack Obama or Senator Hillary Clinton in the presidential election. He supported Senator John McCain instead. After Obama was elected president and Democrats increased their majorities in the House and Senate, he endorsed Republican Saxby Chambliss in the Senate run-off against Democrat Jim Martin and criticized Obama over "spreading the wealth."[32]

In 2012, Miller served as the national co-chair to the campaign of Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich.[33] The same year, Miller endorsed Doug Collins, the Republican candidate in the 9th District of Georgia congressional race.[30]

In 2014, Miller endorsed major Georgia candidates in both parties. He made a TV ad calling for the election of Michelle Nunn, the Democratic U.S. Senate candidate. He appeared in the ad with her, saying he was "angry about what's going on in Washington, partisanship over patriotism" and praised Nunn as a "bridge-builder, not a bridge-burner."[34]

Life after politics[edit]

In August 2005, President Bush appointed Miller to the American Battle Monuments Commission.[35]

In 2005, Miller was elected to the Board of Directors of the National Rifle Association.[36]

Miller was a speaker at "Justice Sunday II," an event organized by conservative Christian evangelicals to combat alleged liberal bias in the federal judiciary of the United States. The event was held in Nashville, Tennessee on August 14, 2005, and featured Tony Perkins and James Dobson. Miller criticized the United States Supreme Court, saying that it had "removed prayer from our public schools ... legalized the barbaric killing of unborn babies and it is ready to discard like an outdated hula hoop the universal institution of marriage between a man and a woman."[37]

The Student Learning Center (SLC) at the University of Georgia was renamed to the Zell B. Miller Learning Center (Miller Learning Center or MLC for short) in October 2008.[38]

Miller's health took a downward turn in the late 2000s when he developed Parkinson's disease and other health concerns, which ended in various complications. In 2016, Miller's grandson, Bryan Miller, started the Miller Institute Foundation as a way to preserve and promote his grandfather's legacy.[39] By October 2017, Miller had officially retired from public life and was undergoing treatment for Parkinson's.[40]

Death[edit]

Miller died on March 23, 2018, at his home in Young Harris, Georgia, from complications of Parkinson's disease.[41][1][4] His state funeral was held in Atlanta on March 28 with incumbent Governor Nathan Deal, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, Senator Johnny Isakson, former Senator Max Cleland, former Lieutenant Governor Pierre Howard and three former U.S. Presidents--Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush—in attendance.[42][43]

Awards[edit]

In 1998, he received an honorary degree in Doctor of Laws from Oglethorpe University.[44]

Published works[edit]

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Zell Miller |

- Miller, Zell (1976). Mountains Within Me.

- Miller, Zell (1983). Great Georgians. ISBN 9993788627.

- Miller, Zell (1984). They Heard Georgia Singing: Great Georgians Vol 2.

- Miller, Zell (1997). Corps Values: Everything You Need to Know I Learned In the Marines. ISBN 1563523876.

- Miller, Zell (1998). "Listen to this Voice" Selected Speeches of Governor Zell Miller. Mercer University Press. ISBN 086554641X.

- Allen, Robert E. (1999). The First Battalion of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima: A Day-By-Day History from Personal Accounts and Official Reports, With Complete Muster Rolls. ISBN 0786405600. (foreword by Miller)

- Miller, Zell (2003). A National Party No More: The Conscience of a Conservative Democrat. Stroud & Hall Publishers. ISBN 0974537616.

- Parker, Dick (2003). What'll Ya Have: A History of the Varsity. Looking Glass. ISBN 1929619189. (foreword by Miller)

- Miller, Zell (2005). A Deficit Of Decency. Stroud & Hall. ISBN 0974537632.

- Zoller, Martha (2005). Indivisible: Uniting Values for a Divided America. Stroud & Hall. ISBN 0974537640. (foreword by Miller)

- Miller, Zell (2007). The Miracle of Brasstown Valley. Stroud & Hall. ISBN 0979646200.

- Miller, Zell (2009). Purt Nigh Gone: The Old Mountain Ways. Stroud & Hall. ISBN 0979646235.

Further reading[edit]

- Eby-Ebersole, Sarah (1999). Signed, Sealed, and Delivered: The Miller Record. ISBN 0865546487.

- Hyatt, Richard (1999). Zell, The Governor Who Gave Georgia HOPE. ISBN 0865545774.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stout, David (March 23, 2018). "Zell Miller, Feisty Democrat Who Sided With G.O.P., Is Dead at 86". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "McKenna Long & Aldridge: Zell Miller". Mckennalong.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Grady Miller". Geni.

- ^ a b c "Zell Miller, Georgia governor and senator with unpredictable streak, dies at 86". The Washington Post. Washington, DC: Nash Holdings LLC. March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Blackwood, Harris: "Zell pens history of Young Harris, signs copies of new book today" Gainesville Times, December 11, 2007

- ^ "Birdie Miller". Geni.

- ^ a b c "University mourns passing of Zell Miller - UGA Today". March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Miller, Zell (1997). Corps Values: Everything You Need to Know I Learned in the Marines. Atlanta, Georgia: Longstreet Press. ISBN 1-56352-387-6.

- ^ a b c Hendrix, Steve (October 17, 2002). "Mountain to Hill" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Georgia Official and Statistical Register, 1985–1988

- ^ a b "Zell Miller: A Democrat Who Insists His Party Left Him (washingtonpost.com)". www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ a b "RBRL/213/ZM_III". russelldoc.galib.uga.edu.

- ^ "Young 2nd In Georgia Primary".

- ^ "Former Gov. Zell Miller remembered as 'strong-willed' public servant who touched many". www.gainesvilletimes.com.

- ^ Times, Ronald Smothers and Special To the New York. "Democrats Hopeful After Miller's Georgia Victory".

- ^ a b Baum, Geraldine (July 13, 1992). "'92 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION : 3 Keynote Speakers Profiled". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Zell, Miller (July 14, 1992). "In Their Own Words: Excerpts From Addresses by Keynote Speakers at Democratic Convention". The New York Times.

- ^ "Scholarships from lottery begin tonight". Rome News-Tribune. Google News Archive. Associated Press. May 28, 1993. p. 8A.

- ^ "Zell Miller on Education". Ontheissues.org. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "'Zigzag Zell' Shrugs Off Criticism". Fox News. Associated Press. August 30, 2004.

- ^ Firestone, David (March 24, 2018). "POLITICS AND THE ECONOMY: THE 2004 CAMPAIGN; Senator Miller, Democratic Maverick, Will Retire" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (May 15, 2005). "REBEL ZELL". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ "Georgia's Miller won't seek re-election". CNN. January 8, 2003.

- ^ Barnes, Fred (October 29, 2003). "Zell Miller Endorses Bush". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ "United States Senator". sos.ga.gov.

- ^ Michael E. Eidenmuller (September 1, 2004). "Zell Miller – 2004 Republican National Convention Address". American Rhetoric. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Barone, Michael. "The National Interest: The Jacksonian Persuasion (9/2/04)". USNews.com. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "– Transcripts". Cnn.com. September 1, 2004. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Zell Miller's Hardball interview – Hardball with Chris Matthews – MSNBC.com". MSNBC. April 26, 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Galloway, Jim (July 21, 2012). "A rare word from Zell Miller: 'I had a late life conversion'". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia: Cox Media. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Miller, Zell (November 5, 2004). "Freedom Victory Is Like That of Lincoln". Lakeland Ledger. Lakeland, Florida: Cox News Service. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Tharpe, Jim (November 27, 2008). "Miller says Chambliss is only man left to halt 'far-left agenda'". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia: Cox Media. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ McCaffrey, Shannon (June 10, 2011). "Gingrich remains a candidate, but how serious?". Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington: Seattle Times Company. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ EndPlay (August 14, 2014). "Zell Miller releases ad throwing support to Michelle Nunn".

- ^ "Bush Asks Zell Miller to Oversee Battle Monuments". Fox News via AP. August 10, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ "NRA Announces New Officers" (Press release). National Rifle Association. April 19, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Edsall, Thomas B. (August 15, 2005). "Conservatives Rally for Justices". Washington Post. Washington, DC: Nash Holdings LLC. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Hampton, Vince (October 17, 2008). "SLC to be rechristened today (w/ video)". The Red and Black. Athens, Georgia: The Red and Black Publishing Company, Inc. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (January 4, 2017). "The Zell Miller Institute aims to be a new player in Georgia politics". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia: Cox Media. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Dave (October 18, 2017). "Zell Miller retires from public life". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Atlanta, Georgia: American City Business Journals. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ "Former Georgia Governor Zell Miller dies at 86". foxnews.com. New York City: Fox News. March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Ex-governors lead state funeral for Zell Miller". AJC. March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Georgia bids final farewell to Zell Miller, the governor who gave Georgia HOPE". 11alive. March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded by Oglethorpe University". Oglethorpe University. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zell Miller |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lester Maddox |

Lieutenant Governor of Georgia January 14, 1975–January 14, 1991 |

Succeeded by Pierre Howard |

| Preceded by Joe Frank Harris |

Governor of Georgia January 14, 1991–January 11, 1999 |

Succeeded by Roy Barnes |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Joe Frank Harris |

Democratic nominee for Governor of Georgia 1990, 1994 |

Succeeded by Roy Barnes |

| Preceded by Ann Richards |

Keynote Speaker of the Democratic National Convention 1992 Served alongside: Bill Bradley, Barbara Jordan |

Succeeded by Evan Bayh |

| Preceded by Michael Coles |

Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from Georgia (Class 3) 2000 |

Succeeded by Denise Majette |

| Preceded by John McCain Colin Powell |

Keynote Speaker of the Republican National Convention 2004 |

Succeeded by Rudy Giuliani |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Paul Coverdell |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from Georgia July 24, 2000–January 3, 2005 Served alongside: Max Cleland, Saxby Chambliss |

Succeeded by Johnny Isakson |

- 1932 births

- 2018 deaths

- 20th-century American politicians

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century Methodists

- 21st-century American politicians

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century Methodists

- American Methodists

- American political writers

- Appointed United States Senators

- Conservatism in the United States

- Deaths from Parkinson's disease

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- Emory University faculty

- Fox News people

- Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats

- Georgia (U.S. state) state senators

- Governors of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Lieutenant Governors of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Mayors of places in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Military personnel from Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Towns County, Georgia

- Politicians from Atlanta

- United States Marines

- 1992 United States presidential electors

- United States Senators from Georgia (U.S. state)

- University of Georgia alumni

- University of Georgia faculty

- Writers from Atlanta

- Young Harris College alumni

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- American male non-fiction writers