Buridan's ass

Buridan's ass is an illustration of a paradox in philosophy in the conception of free will. It refers to a hypothetical situation wherein a donkey that is equally hungry and thirsty is placed precisely midway between a stack of hay and a pail of water. Since the paradox assumes the ass will always go to whichever is closer, it dies of both hunger and thirst since it cannot make any rational decision between the hay and water.[1] A common variant of the paradox substitutes two identical piles of hay for the hay and water; the ass, unable to choose between the two, dies of hunger.

The paradox is named after the 14th-century French philosopher Jean Buridan, whose philosophy of moral determinism it satirizes. Although the illustration is named after Buridan, philosophers have discussed the concept before him, notably Aristotle who used the example of a man equally hungry and thirsty,[2] and Al-Ghazali who used a man faced with the choice of equally good dates.[3]

A version of this situation appears as metastability in digital electronics, when a circuit must decide between two states based on an input that is in itself undefined (neither zero nor one). Metastability becomes a problem if the circuit would take longer time that it should be in this "undecided" state, which is usually set by the speed of the clock the system is running at.

Contents

History[edit]

The paradox predates Buridan; it dates to antiquity, being found in Aristotle's On the Heavens.[2] Aristotle, in ridiculing the Sophist idea that the Earth is stationary simply because it is circular and any forces on it must be equal in all directions, says that is as ridiculous as saying that:[2]

...a man, being just as hungry as thirsty, and placed in between food and drink, must necessarily remain where he is and starve to death.

— Aristotle, On the Heavens 295b, c. 350 BC

However, the Greeks only used this paradox as an analogy in the context of the equilibrium of physical forces.[2]

The 12th century Persian scholar and philosopher al-Ghazali discusses the application of this paradox to human decision making, asking whether it is possible to make a choice between equally good courses without grounds for preference.[2] He takes the attitude that free will can break the stalemate.

Suppose two similar dates in front of a man, who has a strong desire for them but who is unable to take them both. Surely he will take one of them, through a quality in him, the nature of which is to differentiate between two similar things.

Moorish philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), in commentary on Ghazali, takes the opposite view.[2]

Although Buridan nowhere discusses this specific problem, its relevance is that he did advocate a moral determinism whereby, save for ignorance or impediment, a human faced by alternative courses of action must always choose the greater good. In the face of equally good alternatives Buridan believed a rational choice could not be made.[4]

Should two courses be judged equal, then the will cannot break the deadlock, all it can do is to suspend judgement until the circumstances change, and the right course of action is clear.

— Jean Buridan, c. 1340

Later writers satirised this view in terms of an ass which, confronted by both food and water, must necessarily die of both hunger and thirst while pondering a decision.

Discussion[edit]

Some proponents of hard determinism have granted the unpleasantness of the scenario, but have denied that it illustrates a true paradox, since one does not contradict oneself in suggesting that a man might die between two equally plausible routes of action. For example, in his Ethics, Benedict de Spinoza suggests that a person who sees two options as truly equally compelling cannot be fully rational:

[I]t may be objected, if man does not act from free will, what will happen if the incentives to action are equally balanced, as in the case of Buridan's ass? [In reply,] I am quite ready to admit, that a man placed in the equilibrium described (namely, as perceiving nothing but hunger and thirst, a certain food and a certain drink, each equally distant from him) would die of hunger and thirst. If I am asked, whether such a one should not rather be considered an ass than a man; I answer, that I do not know, neither do I know how a man should be considered, who hangs himself, or how we should consider children, fools, madmen, &c.

Other writers[who?] have opted to deny the validity of the illustration. A typical[citation needed] counter-argument is that rationality as described in the paradox is so limited as to be a straw man version of the real thing, which does allow the consideration of meta-arguments. In other words, it is entirely rational to recognize that both choices are equally good and arbitrarily (randomly) pick one instead of starving; although the decision that they are sufficiently the same is also subject to Buridan's ass. The idea that a random decision could be made is sometimes used as an attempted justification for faith or intuitivity (called by Aristotle noetic or noesis). The argument is that, like the starving ass, we must make a choice to avoid being frozen in endless doubt. Other counter-arguments exist.[specify]

According to Edward Lauzinger, Buridan's ass fails to incorporate the latent biases that humans always bring with them when making decisions.[5][full citation needed]

Buridan's principle[edit]

The situation of Buridan's ass was given a mathematical basis in a 1984 paper by American computer scientist Leslie Lamport, in which Lamport presents an argument that, given certain assumptions about continuity in a simple mathematical model of the Buridan's ass problem, there is always some starting condition under which the ass starves to death, no matter what strategy it takes.

Lamport calls this result "Buridan’s principle":

- A discrete decision based upon an input having a continuous range of values cannot be made within a bounded length of time.[6]

Application to digital logic: metastability[edit]

A version of Buridan's principle actually occurs in electrical engineering.[7][8][9][10][11] Specifically, the input to a digital logic gate must convert a continuous voltage value into either a 0 or a 1, which is typically sampled and then processed. If the input is changing and at an intermediate value when sampled, the input stage acts like a comparator. The voltage value can then be likened to the position of the ass, and the values 0 and 1 represent the bales of hay. As in the situation of the starving ass, there exists an input on which the converter cannot make a proper decision, and the output remains balanced in a metastable state between the two stable states for an undetermined length of time, until random noise in the circuit makes it converge to one of the stable states.

"Arbiter" circuits are used to solve this problem[citation needed], by detecting when the comparator is in a metastable state and making an arbitrary choice of output. However no such circuit can completely solve the problem, as the boundary between ambiguous and unambiguous states introduces another binary decision in the arbitrator, with its own metastable state.

The metastability problem is a significant issue in digital circuit design, and metastable states are a possibility wherever asynchronous inputs (digital signals not synchronized to a clock signal) occur. The ultimate reason the problem is manageable is that the probability of a metastable state persisting longer than a given time interval t is an exponentially declining function of t. In electronic devices, the probability of such an "undecided" state lasting longer than a few nanoseconds, while always possible, is very low.

In popular culture[edit]

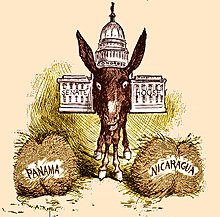

- Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate for president in 1848, was contrasted with Buridan's ass by Abraham Lincoln: "Mr. Speaker, we have all heard of the animal standing in doubt between two stacks of hay, and starving to death. The like would never happen to General Cass; place the stacks a thousand miles apart, he would stand stock still midway between them, and eat them both at once, and the green grass along the line would be apt to suffer some too at the same time."[12] (This being a reference to Cass's support for "popular sovereignty" in the run-up to the Civil War.)

- Buridan's Donkey, a 1932 French comedy film, is named after the paradox

- "Buridan's Ass" is the name of the sixth episode of the first season of the FX television series Fargo.

- In the Doctor Who novel The Eight Doctors, the Fifth and Eighth Doctors are confronted by a Raston Warrior Robot. The Doctors stand exactly the same distance away from the Robot as it approaches them; unable to decide which to attack first (since the Robot attacks by sensing brain patterns, which are identical in the two Doctors), the Robot shuts down.

- The lyrics of a song by Devo, the title track from their album Freedom of Choice, describe a similar situation: "In ancient Rome, there was a poem / About a dog who found two bones" who then, unable to choose between the two, "went in circles till he dropped dead."

- In the 10th season of The Big Bang Theory, Sheldon and Amy discuss the history of Buridan's ass (renamed donkey), and its application to their lives. Amy resolves the paradox (of Sheldon desiring to live in different apartments) by creating a more desirable option by engaging Sheldon in a discussion of the theory and its history.

- On episode 2 of the 3rd season of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (Kimmy's Roommate Lemonades), Kimmy learns about Buridan's Ass from Perry, a possible love interest and also a tour guide for prospective students at Robert Moses College for Everyone.

- Aleksander Fredro, Polish 19th-century poet, tells a story about a donkey who died from hunger because he could not decide between oats and hay, served in two troughs.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Buridan's ass: Oxford Companion to Phrase and Fable". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Rescher, Nicholas (2005). Cosmos and Logos: Studies in Greek Philosophy. Ontos Verlag. pp. 93–99. ISBN 393720265X.

- ^ a b Kane, Robert (2005). A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will. New York: Oxford. p. 37.

- ^ Kinniment, David J. (2008). Synchronization and Arbitration in Digital Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 0470517131.

- ^ "Thought and Process", Lauzinger, Edward, 1994

- ^ Leslie Lamport (December 1984). "Buridan's Principle" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ Leslie Lamport (December 1984). "Buridan's Principle" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-09., p. 8

- ^ Xanthopoulos, Thucydides (2009). Clocking in Modern VLSI Systems. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 191. ISBN 1441902619.

- ^ Niederman, Derrick (2012). The Puzzler's Dilemma. Penguin. p. 130. ISBN 1101560878.

- ^ Zbilut, Joseph P. (2004). Unstable Singularities and Randomness. Elsevier. p. 7. ISBN 0080474691.

- ^ Kinniment, David J. (2008). Synchronization and Arbitration in Digital Systems. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–6. ISBN 0470517131.

- ^ Carl Sandburg (1954), Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, 1960 reprint, New York: Dell, Vol. 1, Ch. 7, "Congressman Lincoln", p. 173.

Bibliography[edit]

- The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2006.

- Knowles, Elizabeth (2006). The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

- Mawson, T.J. (2005). Belief in God. New York, NY: Oxford University (Clarendon) Press. p. 201.

- Rescher, Nicholas (1959). "Choice Without Preference: A Study of the History and of the Logic of the Problem of 'Buridan's Ass'". Kant-Studien. 51: 142–75.

- Zupko, Jack (2003). John Buridan: Portrait of a Fourteenth-Century Arts Master. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 258, 400n71.

- Ullmann-Margalit, E.; Morgenbesser, S. (1977). "Picking and Choos-ing". Social Research. 44: 757–785.

External links[edit]

- Vassiliy Lubchenko (August 2008). "Competing interactions create functionality through frustration". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (31): 10635–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805716105. PMC 2504771. PMID 18669666.