Ranked voting

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

Plurality/majoritarian

|

|

|

|

Other systems & related theory |

|

|

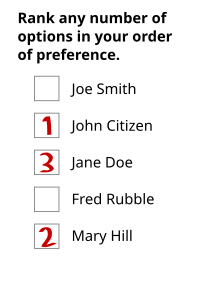

Ranked voting describes certain voting systems in which voters rank outcomes in a hierarchy on the ordinal scale (ordinal voting systems). In some areas ranked-choice voting is called preferential voting, but in other places this term has various other meanings.[1]

When choosing among more than two options, preferential ballots collect more information from voters than first-past-the-post voting (plurality voting). This does not mean that preferential voting is intrinsically better. Arrow's impossibility theorem and Gibbard's theorem prove that all voting systems must make trade-offs between desirable properties.[Mankiw 1][2] There is, accordingly, no consensus among academics or public servants as to the best electoral system.[3] The other major branch of voting systems are cardinal voting systems, where candidates are independently rated, rather than relatively ranked.

There are many types of preferential voting, with several used in governmental elections: Instant-runoff voting is employed in Australian state and federal elections, in Ireland[4] for its presidential elections, and by some jurisdictions in the United States, United Kingdom, and New Zealand. The single transferable vote is used for national elections in the Republic of Ireland and Malta, the Australian Senate, for regional and local elections in Northern Ireland, for all local elections in Scotland, and for some local elections in New Zealand and the United States. Borda count is used in Slovenia[5] and Nauru. Contingent vote and Supplementary vote are also used in a few locations. Condorcet methods have found more use among private organizations and minor parties.

Contents

Variety of systems[edit]

There are many preferential voting systems, so it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between them.

Selection of the Condorcet winner is generally considered by psephologists as the ideal election outcome for a ranked system,[6] so "Condorcet efficiency" is important when evaluating different methods of preferential voting.[7] The Condorcet winner is the one that would win every two-way contest against every other alternative.[Mankiw 2]

Another criterion used to gauge the effectiveness of a preferential voting system is its ability to withstand manipulative voting strategies,[8] when voters cast ballots that do not reflect their preferences in the hope of electing their first choice. This can be rated on at least two dimensions—the number of voters needed to game the system[9] and the complexity of the mechanism necessary.[citation needed]

Instant-runoff voting[edit]

Used in national elections in Australia, this system is said to simulate a series of runoff elections. If no candidate is the first choice of more than half of the voters, then all votes cast for the candidate with the lowest number of first choices are redistributed to the remaining candidates based on who is ranked next on each ballot.[10] If this does not result in any candidate receiving a majority, further rounds of redistribution occur.[10] Or, in other words, "[...] voters would rank their first, second and subsequent choices on the ballot. The candidate with the fewest votes would be dropped and his or her supporters’ second choices would be counted and so on until one candidate emerged with more than 50 per cent."[11]

This method is thought to be resistant to manipulative voting as the only strategies that work against it require voters to highly rank choices they actually want to see lose.[G&F 1] At the same time, this system fails the monotonicity criterion, where ranking a candidate higher can lessen the chances he or she will be elected. Additionally, instant-runoff voting has a lower Condorcet efficiency than similar systems when there are more than four choices.[G&F 2]

Single transferable vote[edit]

This is one of the preferential voting systems most used by countries and states.[notes 1] It is used for electing multi-member constituencies. Any candidates that achieve the number of votes required for election (the "quota") are elected and their surplus votes are redistributed to the voter's next choice candidate.[CEPPS 1] Once this is done, if not all places have been filled then the candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated, and their votes are also redistributed to the voter's next choice. This whole process is repeated until all seats are filled. This method is also called the Hare-Clark system.[CEPPS 1]

When STV is used for single-winner elections, it becomes equivalent to IRV.[12]

Borda count[edit]

In the Borda count, ballots are counted by assigning a point value to each place in each voter's ranking of the candidates, and the choice with the largest number of points overall is elected.[Mankiw 1] This method is named after its inventor, French mathematician Jean-Charles de Borda.[Mankiw 1] Instead of selecting a Condorcet winner, this system may select a choice that reflects an average of the preferences of the constituency.[citation needed]

This system suffers from the fact that the outcome it selects is dependent on the other choices present.[clarification needed] That is, the Borda count does not exhibit independence of irrelevant alternatives[Mankiw 1] or independence of clones. The Borda count can be easily manipulated by adding candidates, called clones, whose views are identical to the preferred candidate's. An example of this strategy can be seen in Kiribati's 1991 presidential nomination contest.[13]

- ^ See table in use by politics below

Uniqueness of votes[edit]

If there are a large number of candidates, which is quite common in single transferable vote elections, then it is likely that many preference voting patterns will be unique to individual voters.[15][16] For example, in the Irish general election, 2002, the electronic votes were published for the Dublin North constituency.[17] There were 12 candidates and almost 44,000 votes cast. The most common pattern (for the three candidates from one party in a particular order) was chosen by only 800 voters, and more than 16,000 patterns were chosen by just one voter each.

The number of possible complete rankings with no ties is the factorial of the number of candidates, N, but with ties it is equal to the corresponding ordered Bell number and is asymptotic to

In the case common to instant-runoff voting in which no ties are allowed, except for unranked candidates who are tied for last place, the number of possible rankings for N candidates is precisely

Use by politics[edit]

- Countries

| Nation | Years in use | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1918–present[20] | Single transferable vote, instant-runoff voting | From 1949, the single transferable vote method has been used for upper house legislative elections.[Sawer 1] Instant-runoff voting is used for lower house elections.[CEPPS 2] |

| Czech Republic[CEPPS 3] | ? | Contingent vote | only used to decide lower house legislative elections |

| Estonia | 1990–c. 2001 | Single transferable vote | As of 2001 single transferable vote had been in use since 1990 to decide legislative elections.[Sawer 1] This is no longer the case.[CEPPS 4] |

| Fiji[21] | 1998–present | Instant-runoff voting | |

| Hong Kong | 1998–present[22] | Instant-runoff voting[23] | Instant-runoff voting is only used in the 4 smallest of Hong Kong's 29 functional constituencies.[24] Officially called preferential elimination voting, the system is identical to the instant-runoff voting.[23] |

| Ireland[Sawer 1] | 1922–present | Instant-runoff voting, single transferable vote | Single transferable vote is used to decide legislative elections only.[Sawer 1] Since 1937 Ireland has used the Instant-runoff voting to decide presidential elections.[Sawer 1] |

| Malta[Sawer 1] | 1921–present | Single transferable vote | |

| Nauru | 1968–present[Sawer 1] | Borda count[CEPPS 5] | Nauru uses the Dowdall system, which is an improved version of the Borda count.[CEPPS 5] |

| New Zealand | 2004–present[25] | Single transferable vote[26] | Instant-runoff voting is used in only some single-seat elections, such as district health boards as well as some city and district councils.[26] |

| Northern Ireland | 1973–present[Sawer 1] | Single transferable vote[27] | Used for local government, European Parliament and the regional legislature, but not elections to Westminster. |

| Papua New Guinea | 2007–present[28] | Instant-runoff voting[G&F 3] | Between 1964 and 1975 PNG used a system that allowed voters the option of ranking candidates.[Sawer 1] Currently, voters can rank only their top three choices.[29] |

| Slovenia | 2000–present[30] | Borda count[CEPPS 6] | Only two seats, which are reserved for Hungarian and Italian minorities, are decided using a Borda count.[CEPPS 6] |

| Sri Lanka[Sawer 2] | 1978–present | Contingent vote and open list[CEPPS 7] | In Sri Lanka contingent vote is used to decide presidential elections[Sawer 1] and legislative elections, open list.[CEPPS 7] |

| Zimbabwe[31] | 1979–1985 | Instant-runoff voting | only used for white candidates |

- Federated states

| Province/state | Country | Years in use | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta[Sawer 1] | Canada | 1952–1954 | Instant-runoff voting | |

| Australian Capital Territory[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1993–present | Single transferable vote | |

| British Columbia[Sawer 1] | Canada | 1926–1955 | Instant-runoff voting | |

| Maine | United States | (2016) 2018–present | Instant-runoff voting ('Ranked-Choice voting') | Originally approved by Maine voters in 2016 general election as ballot referendum to replace First Past The Post system statewide. However the State's constitution, court, and government battles it, resulted in a state law to delay implementation of ranked-choice voting until 2021. Supporters organized for a 2018 people's veto referendum, which received a majority of votes, thus ensuring that ranked-choice voting would be used for future primary and federal elections. |

| Manitoba[Sawer 1] | Canada | 1927–1936 | Instant-runoff voting | |

| New South Wales[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1918–present | Single transferable vote (1918–1926, 1978–present), contingent vote (1926–1928), instant-runoff voting (1929–present) | Since 1978, NSW has used the single transferable vote method to decide upper house legislative elections only. Full preferential voting for lower house since 1981. |

| Northern Territory[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1980 only | ||

| Ontario | Canada | 2018-present | Instant-runoff voting (municipal elections only) | In 2016, the provincial government passed Bill 181, the Municipal Elections Modernization Act, which permitted municipalities to adopt ranked balloting in municipal elections.[32] In the 2018 elections, the first ones conducted under the new legislation, the city of London used ranked balloting,[33] while the cities of Kingston and Cambridge held referendums on whether to adopt ranked ballots for the next municipal elections in 2022.[34] |

| Queensland[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1892–1942, 1962–present | Contingent vote (1892–1942), instant-runoff voting (1962–present) | Full preferential voting used 1962–1992 and since 2016. |

| South Australia[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1929–1935, 1982–present | Instant-runoff voting (1929–1935), single transferable vote (1982–present) | used to decide upper house legislative elections only |

| Tasmania[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1907–present | Single transferable vote (1907–present), instant-runoff voting (1909–present) | Single transferable for the lower house, instant runoff for the upper house. |

| Victoria[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1911–present | Instant-runoff voting (1911–present), single transferable vote (2006–present) | Prior to 1916, Victoria did not use any preferential voting method to decide upper house legislative elections. Instant runoff for the lower house, single transferable for the upper house. Full preferential voting for lower house since 1916. |

| Western Australia[Sawer 1] | Australia | 1907–present | Instant-runoff voting (1907–present), single transferable vote (1989–present) | Instant runoff for the lower house, single transferable for the upper house. Full preferential voting for lower house since 1912. |

- International organizations

| Organization | Years in use | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Union[CEPPS 8] | option to use single transferable vote | Member countries can use either proportional representation (not a type of preferential voting)[citation needed] or single transferable vote to elect MEPs |

- Municipalities

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Toplak, Jurij (2017). "Preferential Voting: Definition and Classification". Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government. 15: 737–61.

- ^ "Interview with Dr. Kenneth Arrow". The Center for Election Science. October 6, 2012.

CES: you mention that your theorem applies to preferential systems or ranking systems. ... But the system that you're just referring to, Approval Voting, falls within a class called cardinal systems. ... Dr. Arrow: And as I said, that in effect implies more information. ... I’m a little inclined to think that score systems where you categorize in maybe three or four classes probably (in spite of what I said about manipulation) is probably the best.

- ^ "Electoral Systems in Europe: An Overview". European Parliament in Brussels: European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation. October 2000. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Toplak, Jurij. "The parliamentary election in Slovenia, October 2004". Electoral Studies. 25 (4): 825–31. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2005.12.006.

- ^ Toplak, Jurij. "The parliamentary election in Slovenia, October 2004". Electoral Studies. 25 (4): 825–31. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2005.12.006.

- ^ Saari, Donald (1995). Basic Geometry of Voting. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 9783540600640.

- ^ Gofman and Feld, 2004, p. 649

- ^ Gofman and Feld, 2004, p. 647

- ^ Gofman and Feld, 2004, p. 652

- ^ a b c d e Bialik, Carl (May 14, 2011). "Latest Issue on the Ballot: How to Hold a Vote". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Bryden, Joan (Oct 19, 2016). "Is Trudeau jockeying to avoid fulfilling promise on electoral reform?". Toronto Star. The Canadian Press. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Q&A: Electoral reform and proportional representation". BBC. 2010-05-11. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Reilley, Benjamin (2002). "Social Choice in the South Seas: Electoral Innovation and the Borda Count in the Pacific Island Countries". International Political Science Review, Vol 23, No. 4, 355–72

- ^ Election database 1 February 2004

- ^ Irish Commission on Electronic Voting 2004

- ^ Dublin County Returning Officer complete table of votes cast Dublin North (zip file)

- ^ Wilf, Herbert S. (January 1994) [1990]. "Chapter 5: Analytic and asymptotic methods". generatingfunctionology (Second ed.). Academic Press. pp. 175–76. ISBN 0127519564. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A007526". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ "Our electoral system". About Australia. Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. May 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Section 54: Voting and other matters". Constitution of Fiji. International Constitutional Law Project. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ The fact that Hong Kong began using preferential voting in 1998 can be seen from two sources:

- Minutes from a 1997 LegCo meeting include a proposal to use "preferential elimination voting" for the three smallest functional constituencies. See, "Legislative Council Bill (Minutes) 11 Sept 97". The Legislative Council Commission. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- 1998 is the first year "preferential elimination voting" can be found in the Hong Kong yearbook. See, "The Electoral System: b. Functional Constituency". Hong Kong Yearbook 1998. Government Information Centre of Hong Kong. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Chapter. 3, Functional Constituencies: The Preferential Elimination System of the 4 SFCs" (PDF). Guidelines on Election-related Activities in respect of the Legislative Council Election. Hong Kong Electoral Affairs Commission. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Functional Constituency Elections". 2000 Legislative Council Elections. Hong Kong Electoral Affairs Commission. 2000. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "STV legislation, background and further information". New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "STV – It's Simple To Vote". New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions – PR/STV Voting System". Electoral Office for Northern Ireland. 2006. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Blackwell, Eoin (June 20, 2012). "Observers urge peaceful PNG election". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Voting". Electoral Commission of Papua New Guinea. 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Article 80: The National Assembly; Composition and Election" (PDF). Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia. United Nations Public Administration Network. pp. 47–48. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ "Negotiations". Administration and Cost of Elections Project. ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "Legislation passes allowing Ontario municipalities to use ranked ballots". The Globe and Mail, June 7, 2016.

- ^ "London, Ont., votes to become 1st Canadian city to use ranked ballots". CBC News Windsor, May 2, 2017.

- ^ Andrew Coyne, "Election reform is coming to Canada — somewhere, somehow, and soon". National Post, October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Instant Runoff Voting (IRV): History of Use in Ann Arbor". Green Party of Michigan. 1998. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Urquhart, Janet (June 28, 2012). "Marks prevails in lawsuit over Aspen election ballots". The Aspen Times. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Ranked-Choice Voting". Alameda County Registrar of Voters. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ McCrea, Lynne (March 3, 2010). vote-voting/ "Burlington Voters Repeal Instant Runoff Voting" Check

|url=value (help). Vermont Public Radio. Retrieved June 29, 2012. - ^ "Choice Voting in Cambridge". FairVote.

- ^ "New Voting Method for November 6, 2007: Hendersonville Pilots Instant Runoff Voting" (PDF). Henderson County Board of Elections. 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Harbin, John (April 8, 2011). "Hendersonville votes to keep instant runoff ballots". BlueRidgeNow.com. Times-News. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Instant Runoff Voting – Coates' Canons". Coates' Canons. 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

November 2013: The 2013 General Assembly repealed all legislation authorizing instant runoff elections in North Carolina. As the law now stands, the kinds of instant runoff voting described in the following post are no longer possible in North Carolina.

- ^ "London's elections: How the voting works". BBC. 3 May 2000. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Voting systems in the UK". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Ranked ballots a reality for 1st time in Ontario municipal elections | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ Gilbert, Curtis (November 2, 2009). "Instant runoff voting FAQ". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Poundstone, William (2009). Gaming the Vote: Why Elections Aren't Fair (And What We Can Do About It). Macmillan. p. 170. ISBN 978-0809048922.

- ^ Baran, Madeleine (November 7, 2011). "Election Day in St. Paul Tuesday". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Ranked Voting Information". Ramsey County. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "City of Takoma Park Election 2011". City Of Takoma Park. 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Instant Runoff Voting Brochure". Town of Telluride. 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Principles of Microeconomics. p. 475.

- ^ Gregory Mankiw (2012). Principles of Microeconomics (6 ed.). South-Western Cengage Learning. pp. 478–79. ISBN 978-0538453042.

- ^ a b "Glossary". ElectionGuide. Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Country Profile: Australia". 2010-07-26. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Country Profile: Czech Republic". 2012-04-25. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Country Profile: Estonia". 2011-04-15. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "Country Profile: Nauru". 2011-11-16. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "Country Profile: Slovenia". 2012-02-28. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "Country Profile: Sri Lanka". 2010-02-18. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Country Profile: European Union". February 4, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ Gofman and Feld, 2004, p. 652

- ^ Gofman and Feld, 2004, p. 647

- ^ Bernard Grofman, Scott L. Feld (2004). "If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule" (PDF). Electoral Studies. 23: 65. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.08.001.

External links[edit]

- Brent, Peter, A Short History of Preferential Voting (in Australia) Mumble Blog, The Australian. 17 April 2011.