ID/LP grammar

ID/LP Grammars are a subset of Phrase Structure Grammars, differentiated from other formal grammars by distinguishing between immediate dominance (ID) and linear precedence (LP) constraints. Whereas traditional phrase structure rules incorporate dominance and precedence into a single rule, ID/LP maintains separate rule sets which need not be processed simultaneously. ID/LP grammars are used in computational linguistics.

For example, a typical phrase structure rule might say , indicating that an S-node dominates an NP-node and a VP-node, and that the NP precedes the VP in the surface string. In ID/LP grammars, this rule would only indicate dominance, and a linear precedence statement, such as , would also be given.

The idea first came to prominence as part of generalized phrase structure grammar;[1][2] the ID/LP approach is also used in head-driven phrase structure grammar,[3] lexical functional grammar, and other unification grammars.

Current work in the Minimalist Program also attempts to distinguish between dominance and ordering. For instance, recent papers by Noam Chomsky have proposed that, while hierarchical structure is the result of the syntactic structure-building operation Merge, linear order is not determined by this operation, and is simply the result of externalization (oral pronunciation, or, in the case of sign language, manual signing).[4][5][6]

Contents

Defining Dominance and Precedence[edit]

Immediate Dominance[edit]

Immediate dominance is the asymmetrical relationship between the mother node of a parse tree and its daughters, where the mother node (to the right of the arrow) is said to immediately dominate the daughter nodes (those to the left of the arrow), but the daughters do not immediately dominate the mother. The daughter nodes are also dominated by any node that immediately dominates the mother node, however this is not an immediate dominance relation.

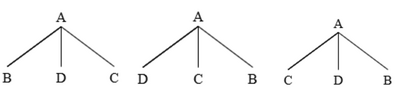

For example the context free rule , shows that the node labelled A immediately dominates nodes labelled B, C, and D, and nodes labelled B, C, and D can be immediately dominated by a node labelled A.

Linear Precedence[edit]

Linear precedence is the order relationship of sister nodes. LP constraints specify in what order sister nodes under the same mother can appear. Nodes that surface earlier in strings precede their sisters. [2] LP can be shown in phrase structure rules in the form to mean B precedes C precedes D, as shown in the tree below.

A rule that has ID constraints but not LP is written with commas between the daughter nodes, for example . Since there is no fixed order for the daughter nodes, it is possible that all three of the trees shown here are generated by this rule.

Alternatively, these relationships can be expressed through linear precedence statements, such as , to mean that anytime B and C are sisters, B must precede C.[2][7]

The principle of transitivity can be applied to LP relations which means that if and , then as well. LP relationships are asymmetric: if B precedes C, C can never precede B. An LP relationship where there can be no intervening nodes is called immediate precedence, while an LP where there can be intervening nodes (those derived from the principle of transitivity) are said to have weak precedence[8].

Grammaticality in IDLP Grammars[edit]

For a string to be grammatical in an IDLP grammar, it must belong to a local subtree that follows at least one ID rule and all LP statements of the grammar. If every possible string generated by the grammar fits this criteria, than it is an ID/LP Grammar. Additionally, for a grammar to be able to be written in ID/LP format, it must have the property of Exhaustive Constant Partial Ordering (ECPO): namely that at least part of the ID/LP relations in one rule is observed in all other rules[2]. For example, the set of rules:

(1)

(2)

does not have the ECPO property, because (1) says that C must always precede D, while (2) says that D must always precede C.

Advantages of ID/LP Grammars[edit]

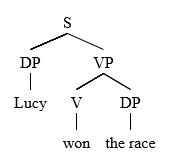

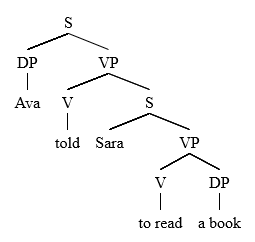

Since LP statements apply regardless of the ID rule context, they allow us to make generalizations across the whole grammar.[2][7] For example given the LP statement , where V is the head of a VP, this means that in any clause in any sentence, V will always surface before its DP sister[7] in any context, as seen in the following examples.

Lucy won the race.

Ava told Sara to read a book.

This can be generalized into a rule that holds across English, , where X is the head of any phrase and YP is its complement. Non-ID/LP Grammars are unable to make such generalizations across the whole grammar, and so must repeat ordering restrictions for each individual context[7].

Separating LP requirements from ID rules also accounts for the phenomena of free word order in natural language. For example in English it is possible to put adverbs before or after a verb and have both strings be grammatical.[7]

John suddenly screamed. John screamed suddenly.

A traditional PS rule would require two separate rules, but this can be described by the single ID/LP rule .This property of ID/LP grammars enables easier cross linguistic generalizations by describing the language specific differences in constituent order with LP statements, separately from the ID rules that are similar across languages[7].

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Gazdar, Gerald; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (1981). "Subcategorization, constituent order, and the notion 'head'". In M. Moortgat; H.v.d. Hulst; T. Hoekstra. The scope of lexical rules. pp. 107–124. ISBN 9070176521.

- ^ a b c d e Gazdar, Gerald; Ewan H. Klein; Geoffrey K. Pullum; Ivan A. Sag (1985). Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell, and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-34455-3.

- ^ Daniels, Mike; Meurers, Detmar (2004). "GIDLP: A grammar format for linearization-based HPSG". Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2007). "Biolinguistic explorations: Design, development, evolution". International Journal of Philosophical Studies. 15 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/09672550601143078.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2011). "Language and other cognitive systems. What is special about language?". Language Learning and Development. 7 (4): 263–278. doi:10.1080/15475441.2011.584041.

- ^ Berwick, Robert C.; et al. (2011). "Poverty of the stimulus revisited". Cognitive Science. 35 (7): 1207–1242. doi:10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01189.x. PMID 21824178.

- ^ a b c d e f Bennett, Paul (1995). A Course in Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar. London: UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-217-5.

- ^ Daniels, M. (2005). Generalized ID/LP grammar: a formalism for parsing linearization-based HPSG grammars. (Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/