Gestalt psychology

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

Gestalt psychology or gestaltism (/ɡəˈʃtɑːlt,

This principle maintains that when the human mind (perceptual system) forms a percept or "gestalt", the whole has a reality of its own, independent of the parts. The original famous phrase of Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka, "the whole is something else than the sum of its parts"[2] is often incorrectly translated[3] as "The whole is greater than the sum of its parts", and thus used when explaining gestalt theory, and further incorrectly applied to systems theory.[4] Koffka did not like the translation. He firmly corrected students who replaced "other" with "greater". "This is not a principle of addition" he said.[5] The whole has an independent existence.

In the study of perception, Gestalt psychologists stipulate that perceptions are the products of complex interactions among various stimuli. Contrary to the behaviorist approach to focusing on stimulus and response, gestalt psychologists sought to understand the organization of cognitive processes (Carlson and Heth, 2010). Our brain is capable of generating whole forms, particularly with respect to the visual recognition of global figures instead of just collections of simpler and unrelated elements (points, lines, curves, etc.).

In psychology, gestaltism is often opposed to structuralism. Gestalt theory, it is proposed, allows for the deconstruction of the whole situation into its elements.[6]

Contents

Origins[edit]

The concept of gestalt was first introduced in philosophy and psychology in 1890 by Christian von Ehrenfels (a member of the School of Brentano). The idea of gestalt has its roots in theories by David Hume, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Immanuel Kant, David Hartley, and Ernst Mach. Max Wertheimer's unique contribution was to insist that the "gestalt" is perceptually primary, defining the parts it was composed from, rather than being a secondary quality that emerges from those parts, as von Ehrenfels's earlier Gestalt-Qualität had been.[citation needed]

Both von Ehrenfels and Edmund Husserl seem to have been inspired by Mach's work Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (Contributions to the Analysis of Sensations, 1886), in formulating their very similar concepts of gestalt and figural moment, respectively. On the philosophical foundations of these ideas see Foundations of Gestalt Theory (Smith, ed., 1988).

Early 20th century theorists, such as Kurt Koffka, Max Wertheimer, and Wolfgang Köhler (students of Carl Stumpf) saw objects as perceived within an environment according to all of their elements taken together as a global construct. This 'gestalt' or 'whole form' approach sought to define principles of perception—seemingly innate mental laws that determined the way objects were perceived. It is based on the here and now, and in the way things are seen. Images can be divided into figure or ground. The question is what is perceived at first glance: the figure in front, or the background.

These laws took several forms, such as the grouping of similar, or proximate, objects together, within this global process. Although gestalt has been criticized for being merely descriptive,[7] it has formed the basis of much further research into the perception of patterns and objects (Carlson et al. 2000), and of research into behavior, thinking, problem solving and psychopathology.

Gestalt therapy[edit]

The founders of Gestalt therapy, Fritz and Laura Perls, had worked with Kurt Goldstein, a neurologist who had applied principles of Gestalt psychology to the functioning of the organism. Laura Perls had been a Gestalt psychologist before she became a psychoanalyst and before she began developing Gestalt therapy together with Fritz Perls.[8] The extent to which Gestalt psychology influenced Gestalt therapy is disputed, however. In any case it is not identical with Gestalt psychology. On the one hand, Laura Perls preferred not to use the term "Gestalt" to name the emerging new therapy, because she thought that the gestalt psychologists would object to it;[9] on the other hand Fritz and Laura Perls clearly adopted some of Goldstein's work.[10] Thus, though recognizing the historical connection and the influence, most gestalt psychologists emphasize that gestalt therapy is not a form of gestalt psychology.

Mary Henle noted in her presidential address to Division 24 at the meeting of the American Psychological Association (1975): "What Perls has done has been to take a few terms from Gestalt psychology, stretch their meaning beyond recognition, mix them with notions—often unclear and often incompatible—from the depth psychologies, existentialism, and common sense, and he has called the whole mixture gestalt therapy. His work has no substantive relation to scientific Gestalt psychology. To use his own language, Fritz Perls has done 'his thing'; whatever it is, it is not Gestalt psychology"[11] With her analysis however, she restricts herself explicitly to only three of Perls' books from 1969 and 1972, leaving out Perls' earlier work, and Gestalt therapy in general as a psychotherapy method.[12]

There have been clinical applications of Gestalt psychology in the psychotherapeutic field long before Perls'ian Gestalt therapy, in group psychoanalysis (Foulkes), Adlerian individual psychology, by Gestalt psychologists in psychotherapy like Erwin Levy, Abraham S. Luchins, by Gestalt psychologically oriented psychoanalysts in Italy (Canestrari and others), and there have been newer developments foremost in Europe, e.g. Gestalt theoretical psychotherapy.

Theoretical framework and methodology[edit]

The school of gestalt practiced a series of theoretical and methodological principles that attempted to redefine the approach to psychological research. This is in contrast to investigations developed at the beginning of the 20th century, based on traditional scientific methodology, which divided the object of study into a set of elements that could be analyzed separately with the objective of reducing the complexity of this object.

The theoretical principles are the following:

- Principle of Totality—The conscious experience must be considered globally (by taking into account all the physical and mental aspects of the individual simultaneously) because the nature of the mind demands that each component be considered as part of a system of dynamic relationships.

- Principle of psychophysical isomorphism – A correlation exists between conscious experience and cerebral activity.

Based on the principles above the following methodological principles are defined:

- Phenomenon experimental analysis—In relation to the Totality Principle any psychological research should take phenomena as a starting point and not be solely focused on sensory qualities.

- Biotic experiment—The school of gestalt established a need to conduct real experiments that sharply contrasted with and opposed classic laboratory experiments. This signified experimenting in natural situations, developed in real conditions, in which it would be possible to reproduce, with higher fidelity, what would be habitual for a subject.[13]

Support from cybernetics and neurology[edit]

In the 1940s and 1950s, laboratory research in neurology and what became known as cybernetics on the mechanism of frogs' eyes indicate that perception of 'gestalts' (in particular gestalts in motion) is perhaps more primitive and fundamental than 'seeing' as such:

- A frog hunts on land by vision... He has no fovea, or region of greatest acuity in vision, upon which he must center a part of the image... The frog does not seem to see or, at any rate, is not concerned with the detail of stationary parts of the world around him. He will starve to death surrounded by food if it is not moving. His choice of food is determined only by size and movement. He will leap to capture any object the size of an insect or worm, providing it moves like one. He can be fooled easily not only by a piece of dangled meat but by any moving small object... He does remember a moving thing provided it stays within his field of vision and he is not distracted.[14]

- The lowest-level concepts related to visual perception for a human being probably differ little from the concepts of a frog. In any case, the structure of the retina in mammals and in human beings is the same as in amphibians. The phenomenon of distortion of perception of an image stabilized on the retina gives some idea of the concepts of the subsequent levels of the hierarchy. This is a very interesting phenomenon. When a person looks at an immobile object, "fixes" it with his eyes, the eyeballs do not remain absolutely immobile; they make small involuntary movements. As a result the image of the object on the retina is constantly in motion, slowly drifting and jumping back to the point of maximum sensitivity. The image "marks time" in the vicinity of this point.[15]

Properties[edit]

The key principles of gestalt systems are emergence, reification, multistability and invariance.[16]

Emergence[edit]

This is demonstrated by the dog picture, which depicts a Dalmatian dog sniffing the ground in the shade of overhanging trees. The dog is not recognized by first identifying its parts (feet, ears, nose, tail, etc.), and then inferring the dog from those component parts. Instead, the dog appears as a whole, all at once. Gestalt theory does not have an explanation for how this perception of a dog appears.

Reification[edit]

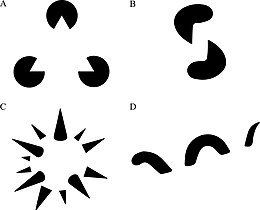

Reification is the constructive or generative aspect of perception, by which the experienced percept contains more explicit spatial information than the sensory stimulus on which it is based.

For instance, a triangle is perceived in picture A, though no triangle is there. In pictures B and D the eye recognizes disparate shapes as "belonging" to a single shape, in C a complete three-dimensional shape is seen, where in actuality no such thing is drawn.

Reification can be explained by progress in the study of illusory contours, which are treated by the visual system as "real" contours.

Multistability[edit]

Multistability (or multistable perception) is the tendency of ambiguous perceptual experiences to pop back and forth unstably between two or more alternative interpretations. This is seen, for example, in the Necker cube and Rubin's Figure/Vase illusion shown here. Other examples include the three-legged blivet and artist M. C. Escher's artwork and the appearance of flashing marquee lights moving first one direction and then suddenly the other. Again, gestalt does not explain how images appear multistable, only that they do.

Invariance[edit]

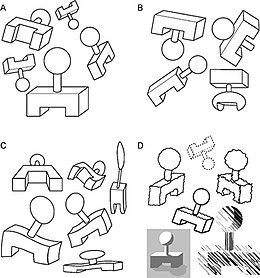

Invariance is the property of perception whereby simple geometrical objects are recognized independent of rotation, translation, and scale; as well as several other variations such as elastic deformations, different lighting, and different component features. For example, the objects in A in the figure are all immediately recognized as the same basic shape, which are immediately distinguishable from the forms in B. They are even recognized despite perspective and elastic deformations as in C, and when depicted using different graphic elements as in D. Computational theories of vision, such as those by David Marr, have provided alternate explanations of how perceived objects are classified.

Emergence, reification, multistability, and invariance are not necessarily separable modules to model individually, but they could be different aspects of a single unified dynamic mechanism.[17]

Prägnanz[edit]

The fundamental principle of gestalt perception is the law of prägnanz [de] (in the German language, pithiness), which says that we tend to order our experience in a manner that is regular, orderly, symmetrical, and simple. Gestalt psychologists attempt to discover refinements of the law of prägnanz, and this involves writing down laws that, hypothetically, allow us to predict the interpretation of sensation, what are often called "gestalt laws".[18]

A major aspect of Gestalt psychology is that it implies that the mind understands external stimuli as whole rather than the sum of their parts. The wholes are structured and organized using grouping laws. The various laws are called laws or principles, depending on the paper where they appear—but for simplicity's sake, this article uses the term laws. These laws deal with the sensory modality of vision. However, there are analogous laws for other sensory modalities including auditory, tactile, gustatory and olfactory (Bregman – GP). The visual Gestalt principles of grouping were introduced in Wertheimer (1923). Through the 1930s and '40s Wertheimer, Kohler and Koffka formulated many of the laws of grouping through the study of visual perception.

- Law of Proximity—The law of proximity states that when an individual perceives an assortment of objects, they perceive objects that are close to each other as forming a group. For example, in the figure that illustrates the Law of proximity, there are 72 circles, but we perceive the collection of circles in groups. Specifically, we perceive that there is a group of 36 circles on the left side of the image, and three groups of 12 circles on the right side of the image. This law is often used in advertising logos to emphasize which aspects of events are associated.[19][20]

- Law of Similarity—The law of similarity states that elements within an assortment of objects are perceptually grouped together if they are similar to each other. This similarity can occur in the form of shape, colour, shading or other qualities. For example, the figure illustrating the law of similarity portrays 36 circles all equal distance apart from one another forming a square. In this depiction, 18 of the circles are shaded dark, and 18 of the circles are shaded light. We perceive the dark circles as grouped together and the light circles as grouped together, forming six horizontal lines within the square of circles. This perception of lines is due to the law of similarity.[20]

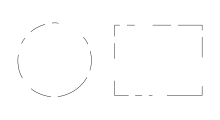

- Law of Closure—The law of closure states that individuals perceive objects such as shapes, letters, pictures, etc., as being whole when they are not complete. Specifically, when parts of a whole picture are missing, our perception fills in the visual gap. Research shows that the reason the mind completes a regular figure that is not perceived through sensation is to increase the regularity of surrounding stimuli. For example, the figure that depicts the law of closure portrays what we perceive as a circle on the left side of the image and a rectangle on the right side of the image. However, gaps are present in the shapes. If the law of closure did not exist, the image would depict an assortment of different lines with different lengths, rotations, and curvatures—but with the law of closure, we perceptually combine the lines into whole shapes.[19][20][21]

- Law of Symmetry—The law of symmetry states that the mind perceives objects as being symmetrical and forming around a center point. It is perceptually pleasing to divide objects into an even number of symmetrical parts. Therefore, when two symmetrical elements are unconnected the mind perceptually connects them to form a coherent shape. Similarities between symmetrical objects increase the likelihood that objects are grouped to form a combined symmetrical object. For example, the figure depicting the law of symmetry shows a configuration of square and curled brackets. When the image is perceived, we tend to observe three pairs of symmetrical brackets rather than six individual brackets.[19][20]

- Law of Common Fate—The law of common fate states that objects are perceived as lines that move along the smoothest path. Experiments using the visual sensory modality found that movement of elements of an object produce paths that individuals perceive that the objects are on. We perceive elements of objects to have trends of motion, which indicate the path that the object is on. The law of continuity implies the grouping together of objects that have the same trend of motion and are therefore on the same path. For example, if there are an array of dots and half the dots are moving upward while the other half are moving downward, we would perceive the upward moving dots and the downward moving dots as two distinct units.[22]

- Law of Continuity—The law of continuity states that elements of objects tend to be grouped together, and therefore integrated into perceptual wholes if they are aligned within an object. In cases where there is an intersection between objects, individuals tend to perceive the two objects as two single uninterrupted entities. Stimuli remain distinct even with overlap. We are less likely to group elements with sharp abrupt directional changes as being one object.[19]

- Law of Good Gestalt—The law of good gestalt explains that elements of objects tend to be perceptually grouped together if they form a pattern that is regular, simple, and orderly. This law implies that as individuals perceive the world, they eliminate complexity and unfamiliarity so they can observe a reality in its most simplistic form. Eliminating extraneous stimuli helps the mind create meaning. This meaning created by perception implies a global regularity, which is often mentally prioritized over spatial relations. The law of good gestalt focuses on the idea of conciseness, which is what all of gestalt theory is based on. This law has also been called the law of Prägnanz.[19] Prägnanz is a German word that directly translates to mean "pithiness" and implies the ideas of salience, conciseness and orderliness.[22]

- Law of Past Experience—The law of past experience implies that under some circumstances visual stimuli are categorized according to past experience. If two objects tend to be observed within close proximity, or small temporal intervals, the objects are more likely to be perceived together. For example, the English language contains 26 letters that are grouped to form words using a set of rules. If an individual reads an English word they have never seen, they use the law of past experience to interpret the letters "L" and "I" as two letters beside each other, rather than using the law of closure to combine the letters and interpret the object as an uppercase U.[22]

Criticisms[edit]

Some of the central criticisms of Gestaltism are based on the preference Gestaltists are deemed to have for theory over data, and a lack of quantitative research supporting Gestalt ideas. This is not necessarily a fair criticism as highlighted by a recent collection of quantitative research on Gestalt perception.[23]

Other important criticisms concern the lack of definition and support for the many physiological assumptions made by gestaltists[24] and lack of theoretical coherence in modern Gestalt psychology.[23]

In some scholarly communities, such as cognitive psychology and computational neuroscience, gestalt theories of perception are criticized for being descriptive rather than explanatory in nature. For this reason, they are viewed by some as redundant or uninformative. For example, Bruce, Green & Georgeson[7] conclude the following regarding gestalt theory's influence on the study of visual perception:

The physiological theory of the gestaltists has fallen by the wayside, leaving us with a set of descriptive principles, but without a model of perceptual processing. Indeed, some of their "laws" of perceptual organisation today sound vague and inadequate. What is meant by a "good" or "simple" shape, for example?

— Bruce, Green & Georgeson, Visual perception: Physiology, psychology and ecology

Gestalt views in psychology[edit]

Gestalt psychologists find it is important to think of problems as a whole. Max Wertheimer considered thinking to happen in two ways: productive and reproductive.[25]

Productive thinking is solving a problem with insight.

This is a quick insightful unplanned response to situations and environmental interaction.

Reproductive thinking is solving a problem with previous experiences and what is already known. (1945/1959).

This is a very common thinking. For example, when a person is given several segments of information, he/she deliberately examines the relationships among its parts, analyzes their purpose, concept, and totality, he/she reaches the "aha!" moment, using what is already known. Understanding in this case happens intentionally by reproductive thinking.

Another gestalt psychologist, Perkins, believes insight deals with three processes:

- Unconscious leap in thinking.[18]

- The increased amount of speed in mental processing.

- The amount of short-circuiting that occurs in normal reasoning.[26]

Views going against the gestalt psychology are:

- Nothing-special view

- Neo-gestalt view

- The Three-Process View

Gestalt psychology should not be confused with the gestalt therapy of Fritz Perls, which is only peripherally linked to gestalt psychology. A strictly gestalt psychology-based therapeutic method is Gestalt Theoretical Psychotherapy, developed by the German gestalt psychologist and psychotherapist Hans-Jürgen Walter and his colleagues in Germany, Austria (Gerhard Stemberger and colleagues) and Switzerland. Other countries, especially Italy, have seen similar developments.

Fuzzy-trace theory[edit]

Fuzzy-trace theory, a dual process model of memory and reasoning, was also derived from Gestalt psychology. Fuzzy-trace theory posits that we encode information into two separate traces: verbatim and gist. Information stored in verbatim is exact memory for detail (the individual parts of a pattern, for example) while information stored in gist is semantic and conceptual (what we perceive the pattern to be). The effects seen in Gestalt psychology can be attributed to the way we encode information as gist.[27][28]

Use in design[edit]

The gestalt laws are used in user interface design. The laws of similarity and proximity can, for example, be used as guides for placing radio buttons. They may also be used in designing computers and software for more intuitive human use. Examples include the design and layout of a desktop's shortcuts in rows and columns.[29]

Music[edit]

An example of the Gestalt movement in effect, as it is both a process and result, is a music sequence. People are able to recognise a sequence of perhaps six or seven notes, despite them being transposed into a different tuning or key.[30]

Quantum cognition modeling[edit]

Similarities between Gestalt phenomena and quantum mechanics have been pointed out by, among others, chemist Anton Amann, who commented that "similarities between Gestalt perception and quantum mechanics are on a level of a parable" yet may give useful insight nonetheless.[31] Physicist Elio Conte and co-workers have proposed abstract, mathematical models to describe the time dynamics of cognitive associations with mathematical tools borrowed from quantum mechanics[32][33] and has discussed psychology experiments in this context. A similar approach has been suggested by physicists David Bohm, Basil Hiley and philosopher Paavo Pylkkänen with the notion that mind and matter both emerge from an "implicate order".[34][35] The models involve non-commutative mathematics; such models account for situations in which the outcome of two measurements performed one after the other can depend on the order in which they are performed—a pertinent feature for psychological processes, as an experiment performed on a conscious person may influence the outcome of a subsequent experiment by changing the state of mind of that person.

See also[edit]

- Amodal perception

- Cognitive grammar

- Fuzzy-trace theory

- Gestaltzerfall

- Graz School

- Hans Wallach

- Hermann Friedmann

- Important publications in Gestalt psychology

- James J. Gibson

- James Tenney

- Kurt Goldstein

- Laws of association

- Mereology

- Optical illusion

- Pál Schiller Harkai

- Pattern recognition (machine learning)

- Pattern recognition (psychology)

- Phenomenology

- Principles of grouping

- Rudolf Arnheim

- Solomon Asch

- Structural information theory

- Topological data analysis

- Wolfgang Metzger

References[edit]

- ^ "gestalt". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Koffka 1935, Principles of Gestalt Psychology, p. 176

- ^ Tuck, Michael (Aug 17, 2010). "Gestalt Principles Applied in Design". Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ^ David Hothersall: History of Psychology, chapter seven, (2004)

- ^ Heider, F. 1977. Cited in Dewey, R.A. 2007. Psychology: An introduction: Chapter four - The Whole is Other than the Sum of the Parts. Retrieved 4/12/2014.

- ^ Humphrey, G (1924). "The psychology of the gestalt". Journal of Educational Psychology. 15 (7): 401–412. doi:10.1037/h0070207.

- ^ a b Bruce, V., Green, P. & Georgeson, M. (1996). Visual perception: Physiology, psychology and ecology (3rd ed.). LEA. p. 110.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Bernd Bocian: Fritz Perls in Berlin 1893–1933. Expressionism – Psychonalysis – Judaism, 2010, p. 190, EHP Verlag Andreas Kohlhage, Bergisch Gladbach.

- ^ Joe Wysong/Edward Rosenfeld (eds): An Oral History of Gestalt Therapy, Highland, New York 1982, The Gestalt Journal Press, p. 12.

- ^ Allen R. Barlow, "Gestalt-Antecedent Influence or Historical Accident", The Gestalt Journal, Volume IV, Number 2, (Fall, 1981)

- ^ Mary Henle 1975: Gestalt Psychology and Gestalt Therapy; Presidential address to Division 24 at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Chicago, September 1975. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 14, pp 23-32.

- ^ See Barlow criticizing Henle: Allen R. Barlow: Gestalt Therapy and Gestalt Psychology. Gestalt – Antecedent Influence or Historical Accident, in: The Gestalt Journal, Volume IV, Number 2, Fall, 1981.

- ^ William Ray Woodward, Robert Sonné Cohen – World views and scientific discipline formation: science studies in the German Democratic Republic : papers from a German-American summer institute, 1988

- ^ Lettvin, J.Y., Maturana, H.R., Pitts, W.H., and McCulloch, W.S. (1961). Two Remarks on the Visual System of the Frog. In Sensory Communication edited by Walter Rosenblith, MIT Press and John Wiley and Sons: New York

- ^ Valentin Fedorovich Turchin – The phenomenon of science – a cybernetic approach to human evolution – Columbia University Press, 1977

- ^ Steven., Lehar, (2003). The World in your Head: A Gestalt View of the Mechanism of Conscious Experience. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. ISBN 0805841768. OCLC 52051454.

- ^ "Gestalt Isomorphism". Sharp.bu.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ a b Sternberg, Robert, Cognitive Psychology Third Edition, Thomson Wadsworth© 2003.

- ^ a b c d e Stevenson, Herb. "Emergence: The Gestalt Approach to Change". Unleashing Executive and Orzanizational Potential. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Soegaard, Mads. "Gestalt Principles of form Perception". Interaction Design. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "Why Your Brain Thinks These Dots Are a Dog". Gizmodo UK. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ^ a b c Todorovic, Dejan. "Gestalt Principles". Scholarpedia.org. Scholarpedia. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b Jäkel, F., Singh, M., Wichmann, F. A., & Herzog, M. H. (2016), "An overview of quantitative approaches in Gestalt perception.", Vision Research, 126: 3–8, doi:10.1016/j.visres.2016.06.004CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Schultz, Duane (2013). A History of Modern Psychology. Burlington: Elsevier Science. p. 291. ISBN 1483270084.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert, Cognitive Psychology Fourth Edition, Thomas Wadsworth© 2006.

- ^ Langley& associates, 1987; Perkins, 1981; Weisberg, 1986,1995"

- ^ Reyna, Valerie (2012). "A new institutionism: Meaning, memory, and development in Fuzzy-Trace Theory". Judgment and Decision Making. 7 (3): 332–359.

- ^ Barghout, Lauren (2014). "Visual Taxometric Approach to Image Segmentation Using Fuzzy-Spatial Taxon Cut Yields Contextually Relevant Regions". Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems: 163–173.

- ^ Soegaard, Mads. "Gestalt principles of form perception". Interaction-design.org. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ Ellis, Willis D. (1999). A source book of Gestalt psychology (Vol 2 ed.). Psychology Press.

- ^ Anton Amann, The Gestalt problem in quantum theory: Generation of molecular shape by the environment. Synthese, October 1993, Volume 97, Issue 1, pp 125–156; Das Gestaltproblem in der Chemie: Die Entstehung molekularer Form unter dem Einfluß der Umgebung, Gestalt Theory, 1992, 14(4), 228-265.

- ^ Conte, Elio; Todarello, Orlando; Federici, Antonio; Vitiello, Francesco; Lopane, Michele; Khrennikov, Andrei; Zbilut, Joseph P. (2007). "Some remarks on an experiment suggesting quantum-like behavior of cognitive entities and formulation of an abstract quantum mechanical formalism to describe cognitive entity and its dynamics". Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 31 (5): 1076–1088. arXiv:0710.5092. Bibcode:2007CSF....31.1076C. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2005.09.061.

- ^ Elio Conte, Orlando Todarello, Antonio Federici, Francesco Vitiello, Michele Lopane, Andrei Khrennikov: A Preliminary Evidence of Quantum Like Behavior in Measurements of Mental States, arXiv:quant-ph/0307201 (submitted 28 July 2003)

- ^ B.J. Hiley: Particles, fields, and observers, Volume I The Origins of Life, Part 1 Origin and Evolution of Life, Section II The Physical and Chemical Basis of Life, pp. 87–106 (PDF)

- ^ Basil J. Hiley, Paavo Pylkkänen: Naturalizing the mind in a quantum framework. In Paavo Pylkkänen and Tere Vadén (eds.): Dimensions of conscious experience, Advances in Consciousness Research, Volume 37, John Benjamins B.V., 2001, ISBN 90-272-5157-6, pages 119-144

- Carlson, Neil R. and Heth, C. Donald (2010) Psychology the Science of Behaviour Ontario, CA: Pearson Education Canada. pp 20–22.

- Smith, Barry (ed.) (1988) Foundations of Gestalt Theory, Munich and Vienna: Philosophia Verlag, 1988.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Gestalt psychology |

- Gestalt psychology on Encyclopædia Britannica

- Gestalt principles article in Scholarpedia, by Dejan Todorović

- Journal "Gestalt Theory - An International Multidisciplinary Journal" in full text (open source)

- International Society for Gestalt Theory and its Applications – GTA

- Embedded Figures in Art, Architecture and Design

- On Max Wertheimer and Pablo Picasso

- On Esthetics and Gestalt Theory

- The World In Your Head – by Steven Lehar

- Gestalt Isomorphism and the Primacy of Subjective Conscious Experience – by Steven Lehar

- The new gestalt psychology of the 21st century

- The Pennsylvania Gestalt Center

- Ecological Approach to Visual Perception

- James J. Gibson in brief