Weighting

The process of weighting involves emphasizing the contribution of particular aspects of a phenomenon (or of a set of data) over others to a final outcome or result; thereby highlighting those aspects in comparison to others in the analysis. That is, rather than each variable in the data set contributing equally to the final result, some of the data is adjusted to make a greater contribution than others. This is analogous to the practice of adding (extra) weight to one side of a pair of scales in order to favour either the buyer or seller.

While weighting may be applied to a set of data, such as epidemiological data, it is more commonly applied to measurements of light, heat, sound, gamma radiation, and in fact any stimulus that is spread over a spectrum of frequencies.

Contents

Weighting and loudness[edit]

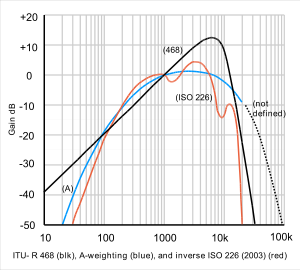

In the measurement of loudness, for example, a weighting filter is commonly used to emphasise frequencies around 3 to 6 kHz where the human ear is most sensitive, while attenuating very high and very low frequencies to which the ear is insensitive. A commonly used weighting is the A-weighting curve, which results in units of dBA sound pressure level. Because the frequency response of human hearing varies with loudness, the A-weighting curve is correct only at a level of 40-phon and other curves known as B, C and D weighting are also used, the latter being particularly intended for the measurement of aircraft noise.

Weighting in audio measurement[edit]

In broadcasting and audio equipment measurements 468-weighting is the preferred weighting to use because it was specifically devised to allow subjectively valid measurements on noise, rather than pure tones. It is often not realised that equal loudness curves, and hence A-weighting, really apply only to tones, as tests with noise bands show increased sensitivity in the 5 to 7 kHz region on noise compared to tones.

Other weighting curves are used in rumble measurement and flutter measurement to properly assess subjective effect.

In each field of measurement, special units are used to indicate a weighted measurement as opposed to a basic physical measurement of energy level. For sound, the unit is the phon (1 kHz equivalent level).

In the fields of acoustics and audio engineering, it is common to use a standard curve referred to as A-weighting, one of a set that are said to be derived from equal-loudness contours.

Weighting and gamma rays[edit]

In the measurement of gamma rays or other ionising radiation, a radiation monitor or dosimeter will commonly use a filter to attenuate those energy levels or wavelengths that cause the least damage to the human body but letting through those that do the most damage, so any source of radiation may be measured in terms of its true danger rather than just its strength. The resulting unit is the sievert or microsievert.

Weighting and television colour components[edit]

Another use of weighting is in television, in which the red, green and blue components of the signal are weighted according to their perceived brightness. This ensures compatibility with black and white receivers and also benefits noise performance and allows separation into meaningful luminance and chrominance signals for transmission.

Weighting and UV factor derivation for sun exposure[edit]

Skin damage due to sun exposure is very wavelength dependent over the UV range 295 to 325 nm, with power at the shorter wavelength causing around 30 times as much damage as the longer one. In the calculation of UV Index, a weighting curve is used which is known as the McKinlay-Diffey Erythema action spectrum.[1]

Weighting in 3D modeling and animation[edit]

Weighting in the context of 3D modeling and animation refers to how closely the components of a soft body follow their "target", "guide", "goal", or "controller". Components (usually vertices) with higher weights follow (or "conform" to) their guide quite closely, but those with lower weights do not. Here are some examples:

Skeleton structure[edit]

Often, when an object is rigged with a skeleton, weights are applied to the vertices near the joints. The vertices closer to the joint will usually have a lower weight assigned; the reason is so that during deformation, the geometry of the skin does not fold in on itself. Weighting in this situation will most of the time be done automatically using skinning techniques but is often done by hand fine tune the skeleton's deformation effects.

Another example of using weights with a skeleton structure would be to actually apply weights to vertices that are not part of a character's skin. An appropriate situation for this method would be the case when an elephant's trunk dangles freely as it walks. The elephant's trunk is rigged with a skeleton and inverse kinematic (IK) curve. Then, a goal curve is created so that the IK curve has something to "aim for" and thus the trunk has a certain shape to which it conforms.

Closer to the end of the trunk, the vertices of the IK curve are given lower weights. Thus, for example, if the goal curve was parented to the elephant and a gravity field was in effect, if the elephant stopped walking, the end of the IK curve and, thus, the end of the trunk would continue to move, dangle back and forth, ultimately coming to a rest in the position determined by the goal curve.

Cloth[edit]

Weights are used with cloth as well. For instance, if a character was being outfitted with a dress, around the waist, the cloth should stay attached to the character, but farther down, its movements should be governed more by effects directly induced by the neighbouring cloth vertices than by the hip movements of the character.

Higher weights are then applied to the cloth vertices close to the hip so that they hug the character quite closely compared to the cloth farther down the dress. To make the dress more realistic, it is possible to assign cloth weights of even 0 to much of the dress because springs hold the cloth together; one must keep in mind, however, that doing this for the entire dress would effectively cancel the attachment of the dress to the character.

See also[edit]

- Weighting curve

- Weighting filter

- A-weighting

- Equal-loudness contour

- ITU-R 468 noise weighting

- Psophometric weighting

- Audio quality measurement

External links[edit]

- Noise measurement briefing

- Calculator for A,C,U, and AU weighting values

- A-weighting filter circuit for audio measurements

- AES pro audio reference definition of "weighting filters"

- What is a decibel?

- Weighting filter according DIN EN 61672-1 2003-10 (DIN-IEC 651) Calculation: frequency f to dBA and dBC

.svg/300px-Acoustic_weighting_curves_(1).svg.png)

_Rumble_Weighting_curves.svg/300px-IEC_98_(1984)_Rumble_Weighting_curves.svg.png)