John Dee

John Dee | |

|---|---|

A 16th-century portrait by an unknown artist[1] | |

| Born | 13 July 1527[2] Tower Ward, London[2] |

| Died | December 1608 or March 1609 (age 81) Mortlake, Surrey, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge Louvain University |

| Known for | Advisor to Queen Elizabeth I |

| Spouse(s) | Katherine Constable Jane Fromond |

| Children | 8 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, alchemy, astrology, Hermeticism, navigation, |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge Christ's College, Manchester |

| Academic advisors | Gemma Frisius, Gerardus Mercator[3] |

| Notable students | Thomas Digges[4] |

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occult philosopher,[5] and advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. He devoted much of his life to the study of alchemy, divination, and Hermetic philosophy. He was also an advocate of England's imperial expansion into a "British Empire", a term he is generally credited with coining.[6]

Viewed from a 21st century perspective, Dee's activities would seem to straddle the worlds of magic and modern science, though this distinction would have been meaningless to him. One of the most learned men of his age, he had been invited to lecture on Euclidean geometry at the University of Paris while still in his early twenties. Dee was an ardent promoter of mathematics and a respected astronomer, as well as a leading expert in navigation, having trained many of those who would conduct England's voyages of discovery.

Simultaneously with these enormous efforts, Dee immersed himself in the worlds of sorcery, astrology and Hermetic philosophy. He devoted much time and effort in the last 30 years or so of his life to attempting to commune with angels in order to learn the universal language of creation and bring about the pre-apocalyptic unity of mankind. A student of the Renaissance Neo-Platonism of Marsilio Ficino, Dee did not draw distinctions between his mathematical research and his investigations into Hermetic magic, angel summoning and divination. Instead he considered all of his activities to constitute different facets of the same quest: the search for a transcendent understanding of the divine forms which underlie the visible world, which Dee called "pure verities".

In his lifetime, Dee amassed one of the largest libraries in England. His high status as a scholar also allowed him to play a role in Elizabethan politics. He served as an occasional advisor and tutor to Elizabeth I and nurtured relationships with her ministers Francis Walsingham and William Cecil. Dee also tutored and enjoyed patronage relationships with Sir Philip Sidney, his uncle Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, and Edward Dyer. He also enjoyed patronage from Sir Christopher Hatton.

Contents

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Dee was born in Tower Ward, London, to Rowland Dee, of Welsh descent,[7][8][9][10][11] and Johanna Wild. His surname "Dee" derived from the Welsh du (black); his grandfather was Bedo Ddu of Nant-y-groes, Pilleth, Radnorshire, and John retained his connection with the locality. His father Roland was a mercer and gentleman courtier to Henry VIII. John Dee claimed to be a descendant of Rhodri the Great, Prince of Wales and constructed a pedigree showing his descent from Rhodri. Dee's family arrived in London in the wake of Henry Tudor's coronation as Henry VII.[8] Jane Dee was the daughter of William Wild.[5]

Dee attended the Chelmsford Chantry School (now King Edward VI Grammar School) from 1535 to 1542.[12] He entered St John's College, Cambridge, in November 1542, aged 15, graduating BA in 1545 or early 1546.[13][14] His abilities recognised, he became an original fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, on its founding by Henry VIII in 1546.[15] At Trinity, the clever stage effects he produced for a production of Aristophanes' Peace procured him the reputation of being a magician that clung to him through life. In the late 1540s and early 1550s, he travelled in Europe, studying at Louvain (1548) and Brussels and lecturing in Paris on Euclid. He studied with Gemma Frisius and became a close friend of the cartographer Gerardus Mercator and cartographer Abraham Ortelius. Dee also travelled extensively throughout Europe meeting and working with as well as learning from other leading continental mathematicians such as Federico Commandino in Italy.[16] He returned to England with an important collection of mathematical and astronomical instruments. In 1552, he met Gerolamo Cardano in London: during their acquaintance they investigated a perpetual motion machine as well as a gem purported to have magical properties.[17]

Rector at Upton-upon-Severn from 1553, Dee was offered a readership in mathematics at Oxford in 1554, which he declined; he was occupied with writing and perhaps hoped for a better position at court.[18] In 1555, Dee became a member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers, as his father had, through the company's system of patrimony.[19]

That same year, 1555, he was arrested and charged with "calculating" for having cast horoscopes of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth; the charges were expanded to treason against Mary.[18][20] Dee appeared in the Star Chamber and exonerated himself, but was turned over to the Catholic Bishop Bonner for religious examination. His strong and lifelong penchant for secrecy perhaps worsening matters, this entire episode was only the most dramatic in a series of attacks and slanders that would dog Dee throughout his life. Clearing his name yet again, he soon became a close associate of Bonner.[18]

Dee presented Queen Mary with a visionary plan for the preservation of old books, manuscripts and records and the founding of a national library, in 1556, but his proposal was not taken up.[18] Instead, he expanded his personal library at his house in Mortlake, tirelessly acquiring books and manuscripts in England and on the European Continent. Dee's library, a centre of learning outside the universities, became the greatest in England and attracted many scholars.[21]

When Elizabeth took the throne in 1558, Dee became her trusted advisor on astrological and scientific matters, choosing Elizabeth's coronation date himself.[22][23] From the 1550s through the 1570s, he served as an advisor to England's voyages of discovery, providing technical assistance in navigation and ideological backing in the creation of a "British Empire", a term that he was the first to use.[24] Dee wrote a letter to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, in October 1574 seeking patronage. He claimed to have occult knowledge of treasure in the Welsh Marches, and of valuable ancient manuscripts kept at Wigmore Castle, knowing that the Lord Treasurer's ancestors came from this area.[25] In 1577, Dee published General and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, a work that set out his vision of a maritime empire and asserted English territorial claims on the New World. Dee was acquainted with Humphrey Gilbert and was close to Sir Philip Sidney and his circle.[24]

In 1564, Dee wrote the Hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica ("The Hieroglyphic Monad"), an exhaustive Cabalistic interpretation of a glyph of his own design, meant to express the mystical unity of all creation. Having dedicated it to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor in an effort to gain patronage, Dee attempted to present it to him during the time of his ascension to the throne of Hungary. This work was esteemed by many of Dee's contemporaries, but the work can not be interpreted today without the secret oral tradition from that era.[26]

He published a "Mathematical Preface" to Henry Billingsley's English translation of Euclid's Elements in 1570, arguing the central importance of mathematics and outlining mathematics' influence on the other arts and sciences.[27] Intended for an audience outside the universities, it proved to be Dee's most widely influential and frequently reprinted work.[28]

One of the important early products of the English School was the first English translation of the Elements of Euclid. This translation was carried out by The Lord Mayor of London Sir Henry Billingsley and not from a Latin translation but direct from the Greek. Published in 1570 this mathematical milestone contained a preface as well as copious notes and supplementary material from John Dee and this preface is considered to be one of Dee’s most important mathematical works.

Later life[edit]

By the early 1580s, Dee was growing dissatisfied with his progress in learning the secrets of nature as well as his failing influence and recognition in court circles. Failure of his proposed calendar revision, imperial recommendations and ambivalent results from exploration of North America had nearly brought his hopes of political patronage to an end. As a result, he began a more energetic turn towards the supernatural as a means to acquire knowledge. Specifically, he sought to contact spirits through the use of a "scryer" or crystal-gazer, which would act as an intermediary between Dee and the angels.[29]

Dee's first attempts with several scryers were not satisfactory, but, in 1582, he met Edward Kelley (then going under the name of Edward Talbot to disguise his conviction for "coining" or forgery), who impressed him greatly with his abilities.[30] Dee took Kelley into his service and began to devote all his energies to his supernatural pursuits.[30] These "spiritual conferences" or "actions" were conducted with an air of intense Christian piety, always after periods of purification, prayer and fasting.[30] Dee was convinced of the benefits they could bring to mankind. (The character of Kelley is harder to assess: some have concluded that he acted with complete cynicism, but delusion or self-deception are not out of the question.[31] Kelley's "output" is remarkable for its sheer volume, its intricacy and its vividness). Dee maintained that the angels laboriously dictated several books to him this way, through Kelley, some in a special angelic or Enochian language.[32][33]

In 1583, Dee met the visiting impoverished yet popular Polish nobleman Albert Łaski who, after overstaying his welcome at court, invited Dee to accompany him on his return to Poland.[20] With some prompting by the "angels" (again through Kelley) and his worsening status at court, Dee was persuaded to go. Dee, Kelley and their families left for the Continent in September 1583, but Łaski proved to be bankrupt and out of favour in his own country.[34] Dee and Kelley began a nomadic life in Central Europe, meanwhile continuing their spiritual conferences, which Dee recorded meticulously in his diaries and almanacs.[32][33] They had audiences with Emperor Rudolf II in Prague Castle and King Stefan Batory of Poland whom they attempted to convince of the importance of angelic communication. The meeting with the Polish King, Stefan Batory, took place at the royal castle at Niepołomice (near Kraków, then the capital of Poland) and was later widely analyzed by Polish historians (Ryszard Zieliński, Roman Żelewski, Roman Bugaj) and writers (Waldemar Łysiak).[citation needed] While generally Dee was accepted as a man of wide and deep knowledge, they mistrusted his connection with the English monarch, Elizabeth I. They could not be sure that their meetings were without political ramifications. Some thought (and still do) that Dee was in fact a spy for the English monarch. Nevertheless, the Polish king, a devout Catholic and very cautious of supernatural media, began their meeting(s) with the affirmation that any prophetic revelations must be in keeping with the teachings of Jesus Christ, the mission of the Holy Catholic Church, and the approval of the Pope.

In 1587, during a spiritual conference in Bohemia, Kelley informed Dee that the angel Uriel had ordered the men to share all their possessions, including their wives. By this time, Kelley had gained some renown as an alchemist and in fact was more sought-after than Dee in this regard: this was a line of work that had prospects for serious and long-term financial gain, especially among the royal families of central Europe. Dee, on the other hand, was more interested in communicating with the angels who he believed would help him solve the mysteries of the heavens through mathematics, optics, astrology, science and navigation. It may be that Kelley in fact wished to end Dee's dependence on him as a scryer for their increasingly lengthy and frequent spiritual conferences.[34] The order for wife-sharing caused Dee great anguish, but he apparently did not doubt its genuineness. They apparently did share wives. However, Dee broke off the conferences immediately afterwards. Dee returned to England in 1589: Kelley went on to be the alchemist for Emperor Rudolf II.[34][35] Nine months later, on 28 February 1588, a son was born to Dee's wife, whom Dee baptised Theodorus Trebonianus Dee and raised as his own. It is possible that this child was Kelley's; Dee was 60 at the time, Edward Kelley was 32.

Final years[edit]

Dee returned to Mortlake after six years abroad to find his home vandalized, his library ruined and many of his prized books and instruments stolen.[21][34] Furthermore, Dee found that increasing criticism of occult practices had made England even more inhospitable to his magical practices and natural philosophy. Dee sought support from Elizabeth, who hoped he could persuade Kelley to return and ease England's economic burdens through alchemy.[36] She finally appointed Dee Warden of Christ's College, Manchester, in 1595.[37] This former College of Priests had been re-established as a Protestant institution by a Royal Charter of 1578.[38]

However, he could not exert much control over the Fellows of that College, who despised or cheated him.[18] Early in his tenure, he was consulted on the demonic possession of seven children, but took little interest in the matter, although he did allow those involved to consult his still extensive library.[18]

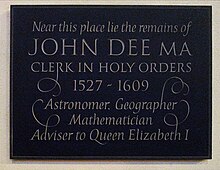

He left Manchester in 1605 to return to London;[39] however, he remained Warden until his death.[40] By that time, Elizabeth was dead, and James I provided no support. Dee spent his final years in poverty at Mortlake, forced to sell off various of his possessions to support himself and his daughter, Katherine, who cared for him until the end.[39] He died in Mortlake late in 1608 or early 1609 aged 82 (there are no extant records of the exact date as both the parish registers and Dee's gravestone are missing).[18][41] In 2013 a memorial plaque to Dee was placed on the south wall of the present church.[42]

Personal life[edit]

Dee was married three times and had eight children. He first married Katherine Constable in 1565; she died in 1574 and their union resulted in no children. His second (also childless) marriage to an unknown woman lasted only a year until her death in 1576.[43] From 1577 to 1601, Dee kept a sporadic diary (also referred to as his "almanac") from which most of what we know about his life during that time has been gleaned.[19] In 1578 he married the 23-year-old Jane Fromond: Dee was 51 at the time. Jane had her own connections to the Elizabethan court: she was a lady in waiting to Elizabeth Clinton, Countess of Lincoln, a position she gave up when she married Dee. When in 1587, Kelley informed Dee of the angel's wish that they share wives, Jane Dee (née Fromond) was the wife Dee shared with him. Although Dee complied with the angel's supposed request for a while, he was apparently distressed by the arrangement and it was one reason why the two men parted company not long thereafter. Some believe that Dee's son Theodore, born nine months later, could have been Kelley's son, not Dee's.[19]

Jane died in Manchester of the bubonic plague and was buried in the Manchester Cathedral burial grounds in March 1604.[44] Michael, born in Prague, died on his father's birthday in 1594. Theodore, born in Třeboň, died in Manchester in 1601. His sons Arthur Dee and Rowland survived him, as did his daughter Katherine "who was his companion to the end".[45] No records exist for his youngest daughters Madinia (sometimes Madima), Frances and Margaret after 1604, so it is widely assumed they died in the same epidemic that took their mother. (Dee had by this time ceased keeping his diary).[18]

While Arthur was a student at the Westminster School, Dee wrote a letter to his headmaster that echoes the worries of boarding school parents in every century. Arthur was an apprentice in much of his father's alchemical and scientific work, and was in fact often his scryer until Kelley came along. Arthur went on to become an alchemist and hermetic author, whose works were published by Elias Ashmole.[18]

As regards Dee's physical appearance, the antiquary John Aubrey[46] gives the following description: "He was tall and slender. He wore a gown like an artist's gown, with hanging sleeves, and a slit.... A very fair, clear sanguine complexion... a long beard as white as milk. A very handsome man."[41]

Achievements[edit]

Thought[edit]

Dee was influenced by the Hermetic and Platonic-Pythagorean doctrines that were pervasive in the Renaissance.[47] He believed that numbers were the basis of all things and the key to knowledge.[22] From Hermeticism, he drew the belief that man had the potential for divine power, and he believed this divine power could be exercised through mathematics.[28] His ultimate goal was to help bring forth a unified world religion through the healing of the breach of the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches and the recapture of the pure theology of the ancients.[22]

Advocacy of English expansion[edit]

From 1570 Dee advocated a policy of political and economic strengthening of England and imperial expansion into the New World.[5] In his manuscript, Brytannicae reipublicae synopsis (1570), he outlined the current state of the Elizabethan Realm[48] and was concerned with trade, ethics and national strength.[5]

His 1576 General and rare memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation was the first volume in an unfinished series planned to advocate the rise of imperial expansion.[49] In the highly symbolic frontispiece, Dee included a figure of Britannia kneeling by the shore beseeching Elizabeth I, to protect her empire by strengthening her navy.[50] Dee used Geoffrey's inclusion of Ireland in Arthur's imperial conquests to argue that Arthur had established a 'British empire' abroad.[51] He further argued that England exploit new lands through colonisation and that this vision could become reality through maritime supremacy.[52][53] Dee has been credited with the coining of the term British Empire,[54] however, Humphrey Llwyd has also been credited with the first use of the term in his Commentarioli Britannicae Descriptionis Fragmentum, published eight years earlier in 1568.[55]

Dee posited a formal claim to North America on the back of a map drawn in 1577–80;[56] he noted Circa 1494 Mr Robert Thorn his father, and Mr Eliot of Bristow, discovered Newfound Land.[57] In his Title Royal of 1580, he invented the claim that Madog ab Owain Gwynedd had discovered America, with the intention of ensuring that England's claim to the New World was stronger than that of Spain.[58] He further asserted that Brutus of Britain and King Arthur as well as Madog had conquered lands in the Americas and therefore their heir Elizabeth I of England had a priority claim there.[59][60]

Reputation and significance[edit]

About ten years after Dee's death, the antiquarian Robert Cotton purchased land around Dee's house and began digging in search of papers and artifacts. He discovered several manuscripts, mainly records of Dee's angelic communications. Cotton's son gave these manuscripts to the scholar Méric Casaubon, who published them in 1659, together with a long introduction critical of their author, as A True & Faithful Relation of What passed for many Yeers between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q. Eliz. and King James their Reignes) and some spirits.[32] As the first public revelation of Dee's spiritual conferences, the book was extremely popular and sold quickly. Casaubon, who believed in the reality of spirits, argued in his introduction that Dee was acting as the unwitting tool of evil spirits when he believed he was communicating with angels. This book is largely responsible for the image, prevalent for the following two and a half centuries, of Dee as a dupe and deluded fanatic.[47] Around the same time the True and Faithful Relation was published, members of the Rosicrucian movement claimed Dee as one of their number.[61] There is doubt, however, that an organized Rosicrucian movement existed during Dee's lifetime, and no evidence that he ever belonged to any secret fraternity.[30] Dee's reputation as a magician and the vivid story of his association with Edward Kelley have made him a seemingly irresistible figure to fabulists, writers of horror stories and latter-day magicians. The accretion of false and often fanciful information about Dee often obscures the facts of his life, remarkable as they are in themselves. It also does nothing to promote his Christian leanings: Dee looked to the angels to speak to him about how he might heal the very deep and serious rifts between the Roman Catholic Church, the Reformed Church of England and the Protestant movement in England.[62] Queen Elizabeth I used him as her court astronomer on a number of occasions not solely because he practised Hermetic arts, but because he was a deeply religious and learned man whom she trusted.

A re-evaluation of Dee's character and significance came in the 20th century, largely as a result of the work of the historians Charlotte Fell-Smith and Dame Frances Yates. Both writers brought into focus the parallel roles magic, science and religion held in the Elizabethan Renaissance. Fell-Smith writes: "There is perhaps no learned author in history who has been so persistently misjudged, nay, even slandered, by his posterity, and not a voice in all the three centuries uplifted even to claim for him a fair hearing. Surely it is time that the cause of all this universal condemnation should be examined in the light of reason and science; and perhaps it will be found to exist mainly in the fact that he was too far advanced in speculative thought for his own age to understand." [63] As a result of this and subsequent re-evaluation, Dee is now viewed as a serious scholar and book-collector, a devoted Christian (albeit during a very confusing time for that faith), an able scientist, and one of the most learned men of his day.[47][64] His personal library at Mortlake was the largest in the country (before it was vandalized), and was created at enormous and sometimes ruinous personal expense; it was considered one of the finest in Europe, perhaps second only to that of De Thou. As well as being an astrological and scientific advisor to Elizabeth and her court, he was an early advocate of the colonisation of North America and a visionary of a British Empire stretching across the North Atlantic.[24]

Dee promoted the sciences of navigation and cartography. He studied closely with Gerardus Mercator, and he owned an important collection of maps, globes and astronomical instruments. He developed new instruments as well as special navigational techniques for use in polar regions. Dee served as an advisor to the English voyages of discovery, and personally selected pilots and trained them in navigation.[18][24] He believed that mathematics (which he understood mystically) was central to the progress of human learning. The centrality of mathematics to Dee's vision makes him to that extent more modern than Francis Bacon, though some scholars believe Bacon purposely downplayed mathematics in the anti-occult atmosphere of the reign of James I.[65] It should be noted, though, that Dee's understanding of the role of mathematics is radically different from our contemporary view.[28][62][66] Dee's promotion of mathematics outside the universities was an enduring practical achievement. As with most of his writings, Dee chose to write in English, rather than Latin, to make his writings accessible to the general public. His "Mathematical Preface" to Euclid was meant to promote the study and application of mathematics by those without a university education, and was very popular and influential among the "mecanicians": the new and growing class of technical craftsmen and artisans. Dee's preface included demonstrations of mathematical principles that readers could perform themselves without special education or training.[28]

During the 20th century, the Municipal Borough of Richmond (now the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames) honoured John Dee by naming a street near Mortlake, where he lived, "Dee Road" after him.[67]

Calendar[edit]

Dee was a friend of Tycho Brahe and was familiar with the work (translated into English by his ward and assistant, Thomas Digges) of Nicolaus Copernicus.[18] Many of his astronomical calculations were based on Copernican assumptions, but he never openly espoused the heliocentric theory. Dee applied Copernican theory to the problem of calendar reform. In 1583, he was asked to advise the Queen about the new Gregorian calendar that had been promulgated by Pope Gregory XIII from October 1582. His advice was that England should accept it, albeit with seven specific amendments. The first of these was that the adjustment should not be the 10 days that would restore the calendar to the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, but by 11 days, which would restore it to the birth of Christ. Another proposal of Dee's was to align the civil and liturgical years, and to have them both start on 1 January. Perhaps predictably, England chose to spurn any suggestions that had papist origins, despite any merit they may objectively have, and Dee's advice was rejected.[22]

Voynich manuscript[edit]

He has often been associated with the Voynich manuscript.[30][68] Wilfrid Michael Voynich, who bought the manuscript in 1912, suggested that Dee may have owned the manuscript and sold it to Rudolph II. Dee's contacts with Rudolph were far less extensive than had previously been thought, however, and Dee's diaries show no evidence of the sale. Dee was, however, known to have possessed a copy of the Book of Soyga, another enciphered book.[69]

Works[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

- Monas Hieroglyphica, 1564

- Preface to Billingsley's Euclid (Billingsley's translation of Euclid's Elements), 1570

- General and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, 1577

- On the Mystical Rule of the Seven Planets, 1582–83

Artefacts[edit]

The British Museum holds several items once owned by Dee and associated with the spiritual conferences:[70]

- Dee's Speculum or Mirror (an obsidian Aztec cult object in the shape of a hand-mirror, brought to Europe in the late 1520s), which was subsequently owned by Horace Walpole.[71] Jennifer Rampling has claimed that Dee never actually owned this object[citation needed]. The item now residing in the British Museum was first attributed to Dee by Horace Walpole. Lord Frederick Campbell had brought "a round piece of shining black marble in a leathern case" to Walpole in an attempt to ascertain the object's provenance. According to Walpole, he responded saying "Oh, Lord, I am the only man in England that can tell you! It is Dr. Dee's black stone". There is no explicit reference to the mirror in any of Dee's surviving writings. The provenance of the Museum's obsidian speculum, as well as the crystal ball, is in fact dubious.[citation needed]

- The small wax seals used to support the legs of Dee's "table of practice" (the table at which the scrying was performed).

- The large, elaborately decorated wax "Seal of God", used to support the "shew-stone", the crystal ball used for scrying.

- A gold amulet engraved with a representation of one of Kelley's visions.

- A crystal globe, six centimetres in diameter. This item remained unnoticed for many years in the mineral collection; possibly the one owned by Dee, but the provenance of this object is less certain than that of the others.[72]

In December 2004, both a shew stone (a stone used for scrying) formerly belonging to Dee and a mid-17th century explanation of its use written by Nicholas Culpeper were stolen from the Science Museum in London; they were recovered shortly afterwards.[73]

Literary and cultural references[edit]

Dee was a popular figure in literary works written by his contemporaries, and he has continued to feature in popular culture ever since, particularly in fiction or fantasy set during his lifetime or that deals with magic or the occult.

16th and 17th centuries[edit]

- Edmund Spenser may refer to Dee in The Faerie Queene (1596).[74]

- William Shakespeare may have modelled the character of Prospero in The Tempest (1610–11) on Dee.[30]

19th century[edit]

- William Harrison Ainsworth includes Dee as a character in his 1840 novel Guy Fawkes.

- Dee is the subject of Henry Gillard Glindoni's painting John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I.[75]

20th century[edit]

The early twentieth century horror author H. P. Lovecraft mentions Dee as one of the translators of the fictional book Al Azif (commonly known as the Necronomicon) in his short fictional essay, History of the Necronomicon, which reads: "An English translation made by Dr. Dee was never printed, and exists only in fragments recovered from the original manuscript."

21st century[edit]

- John Dee appears as the plot's main antagonist "the Walker" in Charlie Fletcher's book Stoneheart (2006)

- Dr. John Dee serves as a main character in The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel series by Michael Scott (2007-2012). He is an English magician and necromancer.

- Phil Rickman casts John Dee as the main detective, investigating the disappearance of the bones of King Arthur during the reign of Elizabeth I in the historical mystery The Bones of Avalon (2010).[76]

- The play Burn Your Bookes (2010) by Richard Byrne examines the relationship between John Dee, Edward Kelley and Edward Dyer.[77]

- The opera Dr Dee: An English Opera, written by Damon Albarn, explores Dee's life and work. It was premiered at the Palace Theatre in Manchester on 1 July 2011[78] and opened at the London Coliseum as part of the London 2012 Festival for the Cultural Olympiad in June 2012.[79][80]

- John Dee appears as an antagonist in the 2017 video game Nioh.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to Charlotte Fell-Smith, this portrait was painted when Dee was 67. It belonged to grandson Rowland Dee and later to Elias Ashmole, who left it to Oxford University.

- ^ a b Benjamin Woolley (2012), The Queen's Conjuror, HarperCollins UK, p. 3, ISBN 9780007401062

- ^ John Dee at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ "British Society for the History of Mathematics". Dcs.warwick.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2010-05-16. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, R. Julian (2006) [2004]. "Dee, John (1527–1609)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7418. Retrieved 6 December 2011. ((subscription or UK public library membership required))

- ^ Gwyn A. Williams, When Was Wales? A History of the Welsh (London: Penguin, 1985), p. 124.

- ^ "Blogs - Wales - John Dee, magician to Queen Elizabeth". BBC. 2010-12-18. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ a b Jones and Chambers 1959.

- ^ "Dee biography". History.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ "Welsh Journals Online". Welshjournals.llgc.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ Poole, Robert. "John Dee and the English Calendar: Science, Religion and Empire". The Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13.

- ^ Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company. p. 15. ISBN 9781291940411. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company. pp. 15 & 16. ISBN 9781291940411. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "A true & faithful relation of what passed for many yeers between Dr John Dee ... and some spirits (London, 1659)". St John's College, Cambridge. 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company. p. 15. ISBN 9781291940411. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ https://thonyc.wordpress.com/2013/07/13/john-dee-the-mathematicall-praeface-and-the-english-school-of-mathematics/

- ^ Gerolamo Cardano (trans. by Jean Stoner) (2002). De Vita Propria (The Book of My Life). New York: New York Review of Books. viii.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company.

- ^ a b c Julian Roberts, ed. (2005). "A John Dee Chronology, 1509–1609". Renaissance Man: The Reconstructed Libraries of European Scholars: 1450–1700 Series One: The Books and Manuscripts of John Dee, 1527–1608. Adam Matthew Publications. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ a b "Mortlake". The Environs of London: County of Surrey. 1: 364–88. 1792. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ a b "Books owned by John Dee". St. John's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d Dr. Robert Poole (6 September 2005). "John Dee and the English Calendar: Science, Religion and Empire". Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ Szönyi, György E. (2004). "John Dee and Early Modern Occult Philosophy". Literature Compass. 1 (1): 1–12.

- ^ John Strype, Annals of the Reformation, Oxford (1824), vol.ii, part ii, no. XLV, 558–563

- ^ Forshaw, Peter J. (2005). "The Early Alchemical Reception of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica". Ambix. Maney Publishing. 52 (3): 247–269. doi:10.1179/000269805X77772.

- ^ "John Dee (1527–1608): Alchemy – the Beginnings of Chemistry" (PDF). Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d Stephen Johnston (1995). "The identity of the mathematical practitioner in 16th-century England". Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Frank Klaassen (August 2002). "John Dee's Conversations with Angels: Cabala, alchemy, and the end of nature". Canadian Journal of History.

- ^ a b c d e f Calder, I. R. F. (1952). "John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist". University of London. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ "Dee, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2006. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ a b c Meric Casaubon. A True & Faithful Relation of What passed for many Yeers between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q. Eliz. and King James their Reignes) and some spirits. New York: Magickal Childe Pub. ISBN 0-939708-01-9.

- ^ a b Dee, John. Quinti Libri Mysteriorum. British Library.

- ^ a b c d Mackay, Charles (1852). "4". Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. London: Office of the National Illustrated Library.

- ^ "History of the Alchemy Guild". International Alchemy Guild. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 26 October 2006. (Subscription required (help)).

- ^ “Although it is indeed probable that Kelly was more accomplished and also more devoted to pursuing the way of transmuting base metals to gold, his master approached alchemy in a more subtle and complex way. He did not stand next to the furnace and the alembic day and night, but in his diaries he documented his practical experiments.”Szőnyi, György E. (2015). "'Layers of Meaning in Alchemy in John Dee's Monas hieroglyphica and its Relevance in a Central European Context'" (PDF). Centre for Renaissance Texts, 2015, 100.

- ^ Dee, John (1842) Diary. Manchester: Chetham Society; p. 33

- ^ "John Dee". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). London: Cambridge University Press. 1911.

- ^ a b Fell-Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee: 1527–1608: Appendix 1. London: Constable and Company.

- ^ Frangopulo, N. J. (1962) Rich Inheritance. Manchester: Education Committee; pp. 129–30

- ^ a b John Aubrey (1898). Rev. Andrew Clark, ed. Brief Lives chiefly of Contemporaries set down John Aubrey between the Years 1669 and 1696. Clarendon Press.

- ^ "John Dee of Mortlake Society-Home". Johndeemortlakesoc.org. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ "ALCHEMICAL MANCHESTER - THE DEE CONNECTION". Uncarved.org. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ Manchester Cathedral Archive, MS 1

- ^ "Appendix 1 : The Descendants of John Dee" (PDF). Johndee.org. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ Aubrey's great-grandfather William Aubrey was a cousin "and intimate acquaintance" of Dee.

- ^ a b c Walter I. Trattner (January 1964). "God and Expansion in Elizabethan England: John Dee, 1527–1583". Journal of the History of Ideas. 25 (1): 17–34. doi:10.2307/2708083. JSTOR 2708083.

- ^ William Howard Sherman John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance, Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1997 ISBN 1-55849-070-1

- ^ Frances Amelia Yates Astraea

- ^ Virginia Hewitt, 'Britannia (fl. 1st–21st cent.)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- ^ O. J. Padel, 'Arthur (supp. fl. in or before 6th cent.)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- ^ "Imperial ambition". National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ 1577 J. DEE Arte Navigation 65 OED Online Retrieved 1 April 2009

- ^ Sherman, William Howard. John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance, p. 148. University of Massachusetts Press, 1995. ISBN 1-55849-070-1

- ^ Nicholls, Andrew D. The Jacobean Union: A Reconsideration of British Civil Policies under the Early Stuarts (Volume 64 of Contributions to the Study of World History), p. 19, n. 14. . Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999. ISBN 0-313-30835-7

- ^ R. C. D. Baldwin, 'Thorne, Robert, the elder (c.1460–1519)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- ^ :(BL, Cotton Augustus 1.I.i)

- ^ J. E. Lloyd, 'Madog ab Owain Gwynedd (supp. fl. 1170)', rev. J. Gwynfor Jones, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Ken MacMillan. "Discourse on history, geography, and law: John Dee and the limits of the British empire, 1576–80". Canadian Journal of History, April 2001.

- ^ Robert W. Barone. "Madoc and John Dee: Welsh Myth and Elizabethan Imperialism". The Elizabethan Review. Robert W. Barone is Professor of History at the University of Montevallo

- ^ Ron Heisler (1992). "John Dee and the Secret Societies". The Hermetic Journal.

- ^ a b Katherine Neal (1999). "The Rhetoric of Utility: Avoiding Occult Associations For Mathematics Through Profitability and Pleasure" (PDF). University of Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Fell-Smith, Charlotte "John Dee: 1527–1608" Constable & Company Ltd. London. 1909

- ^ Frances A. Yates (1987). Theatre of the World. London: Routledge. p. 7.

- ^ Brian Vickers (July 1992). "Francis Bacon and the Progress of Knowledge". Journal of the History of Ideas. 53 (3): 495–518. doi:10.2307/2709891. JSTOR 2709891.

- ^ Stephen Johnston (1995). "Like father, like son? John Dee, Thomas Digges and the identity of the mathematician". Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Green, James. The Streets of Richmond and Kew (1990 ed.). Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 0950819859.

- ^ Rugg, Gordon (July 2004). "The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- ^ Reeds, Jim (1996). "John Dee and the Magic Tables in the Book of Soyga" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-05. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ "Dr Dee's magic". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Dr Dee's mirror". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-07-07.

- ^ "BSHM Gazetteer – LONDON: British Museum, British Library and Science Museum". British Society for the History of Mathematics. August 2002. Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Adam Fresco (11 December 2004). "Museum thief spirits away old crystal ball". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Woolley, Benjamin The Queen's Conjuror: The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. New York: Henry Holt and Company (2001)

- ^ Brown, Mark (17 January 2016). "John Dee painting originally had circle of human skulls, x-ray imaging reveals". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Bones of Avalon: Being Edited from the Most Private Documents of Dr. John Dee, Astrologer and Consultant to Queen Elizabeth". Fiction Book Review. Publishers Weekly. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ^ Horwitz, Jane. Backstage: 'Burn Your Bookes' at Taffety Punk, Folger's 2010–2011 season in The Washington Post, 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Damon Albarn's Dr Dee". BBC 6 music news. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Church, Michael (27 June 2012). "First night: Dr Dee, English National Opera, London". The Independent. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Hickling, Alfred (2 July 2011). "Dr Dee, Palace Theatre, Manchester". The Guardian. London.

References[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- Dee, John Quinti Libri Mysteriorum. British Library, MS Sloane Collection 3188. Also available in a fair copy by Elias Ashmole, MS Sloane 3677.

- Dee, John John Dee's five books of mystery: original sourcebook of Enochian magic: from the collected works known as Mysteriorum libri quinque edited by Joseph H. Peterson, Boston: Weiser Books ISBN 1-57863-178-5.

- Dee, John The Mathematicall Praeface to the Elements of Geometrie of Euclid of Megara (1570). New York: Science History Publications (1975) ISBN 0-88202-020-X

- Dee, John John Dee on Astronomy: Propaedeumata Aphoristica (1558 & 1568) edited by Wayne Shumaker, Berkeley: University of California Press ISBN 0-520-03376-0

- Dee, John. Autobiographical tracts of John Dee, Warden of the College of Manchester, ed. James Crossley. Chetham Society Publications, Vol XXIV. Manchester, 1851.

- Dee, John. Diary for the years 1595–1601, ed. John E. Bailey. Privately printed, 1880.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Cajori, Florian A History of Mathematical Notations New York: Cosimo (2007) ISBN 1-60206-684-1

- Calder, I. R. F. John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist PhD Dissertation, London: The Warburg Institute, London University (1952) Available online

- Canny, Nicholas (2001). The Origins of Empire: The Oxford History of the British Empire, Volume I. Oxford University Press (1998). ISBN 0-19-924676-9.

- Casaubon, M. A True and Faithful Relation of What Passed for many Yeers Between Dr. John Dee ... (1659) repr. "Magickal Childe" ISBN 0-939708-01-9 New York (1992)

- Clucas, Stephen, ed. John Dee: interdisciplinary studies in Renaissance thought. Dordrecht: Springer (2006) ISBN 1-4020-4245-0

- Clucas, Stephen, ed. John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica. Ambix Special Issue. Vol. 52, Part 3, 2005, includes articles by Clulee, Norrgren, Forshaw and Bayer.

- Clulee, Nicholas H. John Dee's Natural Philosophy: between science and religion. London: Routledge (1988) ISBN 0-415-00625-2

- Fell-Smith, Charlotte. John Dee: 1527–1608. London: Constable and Company (1909) Available online.

- French, Peter J. John Dee: the world of an Elizabethan magus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (1972) ISBN 0-7102-0385-3

- Håkansson, Håkan. Seeing the Word: John Dee and Renaissance occultism. Lund: Lunds Universitet, 2001. ISBN 91-974153-0-8 Available online

- Jones, John James; Chambers, Llewelyn Gwyn (1959), "Dee, John (1527–1608), mathematician and astronomer", Dictionary of Welsh Biography, National Library of Wales, retrieved 27 March 2018

- Kugler, Martin. Astronomy in Elizabethan England, 1558 to 1585: John Dee, Thomas Digges, and Giordano Bruno. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry (1982)

- Louv, Jason. John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochian Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World." Inner Traditions (April 17, 2018) ISBN 1620555891/ISBN 978-1620555897 available at Amazon.com

- (in French) Mandosio, Jean-Marc. D'or et de sable (chapitre IV. Magie et mathématiques chez John Dee, pp. 143–170), Paris, éditions de l'Encyclopédie des Nuisances, (2008) ISBN 2-910386-26-0

- Morris, Tom. John Dee and Edward Kelley (2013) Available online

- Parry, Glyn. The Arch-Conjuror of England: John Dee and Magic at the Courts of Renaissance Europe New Haven: Yale University Press, (2012) ISBN 978-0300117196

- Sherman, William Howard. John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press (1995) ISBN 1-55849-070-1

- Stark, Ryan. Rhetoric, Science, and Magic in Seventeenth-Century England. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2009.

- Vickers, Brian ed. Occult & Scientific Mentalities in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1984) ISBN 0-521-25879-0

- Woolley, Benjamin (March 2002) [2001], The Queen’s Conjuror: The Life and Magic of Dr. Dee (New ed.), London: Flamingo: HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN 978-0006552024

- Yates, Frances The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London: Routledge (2001) ISBN 0-415-25409-4

- Yates, Frances. "Renaissance Philosophers in Elizabethan England: John Dee and Giordano Bruno." in her Lull & Bruno: Collected Essays Vol. I. London: Routledge & Kegan (1982) ISBN 0-7100-0952-6

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Dee, John. |

- Works by John Dee at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Dee at Internet Archive

- The Private Diary of Dr. John Dee, and the Catalogue of His Library of Manuscripts Full view book with PDF download at Google Books

- The Private Diary of Dr. John Dee, and the Catalogue of His Library of ... with James Orchard Full view book with PDF download at Internet Archive

- The Calls of Enoch with Edward Kelley Full view book at Google Books

- John Dee reports of Dee and Kelley's conversations with Angels edited in PDF by Clay Holden: Mysteriorum Liber Primus (with Latin translations), Notes to Liber Primus by Clay Holden, Mysteriorum Liber Secundus, Mysteriorum Liber Tertius

- The J.W. Hamilton-Jones translation of Monas Hieroglyphica from Twilit Grotto: Archives of Western Esoterica

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "John Dee", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Bibliography of John Dee's diary and Enochian manuscripts

- "Monas Hieroglyphica" - A webinar by Peter Forshaw about John Dee on the website of the Ritman Library, Amsterdam.

- Forshaw, Peter, 'The Early Alchemical Reception of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica,' Ambix, Vol. 52:3 (2005)

- Forshaw, Peter, 'The Hermetic Frontispiece: Contextualising John Dee's Hieroglyphic Monad', Ambix, Vol. 64:1 (2017)

- Selwood, Dominic. "Dr John Dee: Mathematician, Scientist, Magus and Conjuror (2013)

- John Dee

- 1527 births

- 1600s deaths

- 16th-century English mathematicians

- 16th-century English people

- 16th-century philosophers

- Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge

- Angelic visionaries

- Christian Kabbalists

- Creators of writing systems

- English alchemists

- English astrologers

- English astronomers

- English geographers

- English mathematicians

- English occult writers

- English people of Welsh descent

- English philosophers

- Enochian magic

- Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Hermeticists

- Library history

- Mortlake, London

- Mystics

- People of the Elizabethan era

- People of the Tudor period

- University of Leuven alumni

- Welsh mathematicians

- 16th-century occultists

- 16th-century alchemists

- 17th-century alchemists

- 16th-century astrologers

- 17th-century astrologers