Substance theory

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Substance theory, or substance–attribute theory, is an ontological theory about objecthood, positing that a substance is distinct from its properties. A thing-in-itself is a property-bearer that must be distinguished from the properties it bears.[1]

Substance is a key concept in ontology and metaphysics, which may be classified into monist, dualist, or pluralist varieties according to how many substances or individuals are said to populate, furnish, or exist in the world. According to monistic views, there is only one substance. Stoicism and Spinoza, for example, hold monistic views, that pneuma or God, respectively, is the one substance in the world. These modes of thinking are sometimes associated with the idea of immanence. Dualism sees the world as being composed of two fundamental substances, for example, the Cartesian substance dualism of mind and matter. Pluralist philosophies include Plato's Theory of Forms and Aristotle's hylomorphic categories.

Contents

Ancient Greek philosophy[edit]

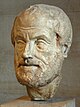

Aristotle[edit]

Aristotle used the term "substance" (Greek: οὐσία ousia) in a secondary sense for genera and species understood as hylomorphic forms. Primarily, however, he used it with regard to his category of substance, the specimen ("this person" or "this horse") or individual, qua individual, who survives accidental change and in whom the essential properties inhere that define those universals.

A substance—that which is called a substance most strictly, primarily, and most of all—is that which is neither said of a subject nor in a subject, e.g. the individual man or the individual horse. The species in which the things primarily called substances are, are called secondary substances, as also are the genera of these species. For example, the individual man belongs in a species, man, and animal is a genus of the species; so these—both man and animal—are called secondary substances.[2]

— Aristotle, Categories 2a13 (trans. J. L. Ackrill)

In chapter 6 of book I the Physics Aristotle argues that any change must be analysed in reference to the property of an invariant subject: as it was before the change and thereafter. Thus, in his hylomorphic account of change, matter serves as a relative substratum of transformation, i.e., of changing (substantial) form. In the Categories, properties are predicated only of substance, but in chapter 7 of book I of the Physics, Aristotle discusses substances coming to be and passing away in the "unqualified sense" wherein primary substances (πρῶται οὐσίαι; Categories 2a35) are generated from (or perish into) a material substratum by having gained (or lost) the essential property that formally defines substances of that kind (in the secondary sense). Examples of such a substantial change include not only conception and dying, but also metabolism, e.g., the bread a man eats becomes the man. On the other hand, in accidental change, because the essential property remains unchanged, by identifying the substance with its formal essence, substance may thereby serve as the relative subject matter or property-bearer of change in a qualified sense (i.e., barring matters of life or death). An example of this sort of accidental change is a change of color or size: a tomato becomes red, or a juvenile horse grows.

Aristotle thinks that in addition to primary substances (which are particulars), there are secondary substances (δεύτεραι οὐσίαι), which are universals (Categories 2a11–a18).[3]

Neither the "bare particulars" nor "property bundles" of modern theory have their antecedent in Aristotle, according to whom, all matter exists in some form. There is no prime matter or pure elements, there is always a mixture: a ratio weighing the four potential combinations of primary and secondary properties and analysed into discrete one-step and two-step abstract transmutations between the elements.[citation needed]

However, according to Aristotle's theology, a form of invariant form exists without matter, beyond the cosmos, powerless and oblivious, in the eternal substance of the unmoved movers.

Stoicism[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (December 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Stoics rejected the idea that incorporeal beings inhere in matter, as taught by Plato. They believed that all being is corporeal infused with a creative fire called pneuma. Thus they developed a scheme of categories different from Aristotle's based on the ideas of Anaxagoras and Timaeus.

Neoplatonism[edit]

Neoplatonists argue that beneath the surface phenomena that present themselves to our senses are three higher spiritual principles or hypostases, each one more sublime than the preceding. For Plotinus, these are the soul or world-soul, being/intellect or divine mind (nous), and "the one".[4]

Early modern philosophy[edit]

René Descartes means by a substance an entity which exists in such a way that it needs no other entity in order to exist. Therefore, only God is a substance in this strict sense. However, he extends the term to created things, which need only the concurrence of God to exist. He maintained that two of these are mind and body, each being distinct from the other in their attributes and therefore in their essence, and neither needing the other in order to exist. This is Descartes' substance dualism.

Baruch Spinoza denied Descartes' "real distinction" between mind and matter. Substance, according to Spinoza, is one and indivisible, but has multiple "attributes". He regards an attribute, though, as "what we conceive as constituting the [single] essence of substance". The single essence of one substance can be conceived of as material and also, consistently, as mental. What is ordinarily called the natural world, together with all the individuals in it, is immanent in God: hence his famous phrase deus sive natura ("God or Nature").

John Locke views substance through a corpuscularian lens where it exhibits two types of qualities which both stem from a source. He believes that humans are born tabula rasa or “blank slate” – without innate knowledge. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding Locke writes that “first essence may be taken for the very being of anything, whereby it is, what it is.” If humans are born without any knowledge, the way to receive knowledge is through perception of a certain object. But, according to Locke, an object exists in its primary qualities, no matter whether the human perceives it or not; it just exists. For example, an apple has qualities or properties that determine its existence apart from human perception of it, such as its mass or texture. The apple itself is also “pure substance in which is supposed to provide some sort of ‘unknown support’ to the observable qualities of things”[vague] that the human mind perceives.[5] The foundational or support qualities are called primary essences which “in the case of physical substances, are the underlying physical causes of the object's observable qualities”.[6] But then what is an object except “the owner or support of other properties”? Locke rejects Aristotle’s category of the forms, and develops mixed ideas about what substance or “first essence” means. Locke’s solution to confusion about first essence is to argue that objects simply are what they are – made up of microscopic particles existing because they exist. According to Locke, the mind cannot completely grasp the idea of a substance as it “always falls beyond knowledge”.[7] There is a gap between what first essence truly means and the mind’s perception of it that Locke believes the mind cannot bridge, objects in their primary qualities must exist apart from human perception.

The molecular combination of atoms in first essence then forms the solid base that humans can perceive and add qualities to describe - the only way humans can possibly begin to perceive an object. The way to perceive the qualities of an apple is from the combination of the primary qualities to form the secondary qualities. These qualities are then used to group the substances into different categories that “depend on the properties [humans] happen to be able to perceive”.[7] The taste of an apple or the feeling of its smoothness are not traits inherent to the fruit but are the power of the primary qualities to produce an idea about that object in the mind.[8] The reason that humans can’t sense the actual primary qualities is the mental distance from the object; thus, Locke argues, objects remain nominal for humans.[9] Therefore, the argument then returns to how “a philosopher has no other idea of those substances than what is framed by a collection of those simple ideas which are found in them.”[10] The mind’s conception of substances “[is] complex rather than simple” and “has no (supposedly innate) clear and distinct idea of matter that can be revealed through intellectual abstraction away from sensory qualities”.[11]

The last quality of substance is the way the perceived qualities seem to begin to change – such as a candle melting; this quality is called the tertiary quality. Tertiary qualities “of a body are those powers in it that, by virtue of its primary qualities, give it the power to produce observable changes in the primary qualities of other bodies”; “the power of the sun to melt wax is a tertiary quality of the sun”.[12] They are “mere powers; qualities such as flexibility, ductility; and the power of sun to melt wax”. This goes along with[vague] “passive power: the capacity a thing has for being changed by another thing”.[13] In any object, at the core are the primary qualities (unknowable by the human mind), the secondary quality (how primary qualities are perceived), and tertiary qualities (the power of the combined qualities to make a change to itself

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, neither "power", nor "qualities" can grammatically serve as the referent of "itself". (June 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

and other objects). The corpuscularian hypothesis, by[vague] Robert Boyle, states that "all material bodies are composites of ultimately small[vague] particles of matter" that "have the same material qualities[vague] as the larger composite bodies do".[14] Using this basis, Locke defines his first group, primary qualities, as "the ones that a body doesn't lose, however much it alters".[15] The materials retain their primary qualities even if they are broken down because of the unchanging nature of their atomic particles.[14] If someone is curious about an object and they[who?] say it is solid and extended, these two descriptors are primary qualities.[16] The second group consists of secondary qualities which are "really nothing but the powers to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities".[15] Locke argues that the impressions our senses perceive from the objects (i.e. taste, sounds, colors, etc.) are not natural properties of the object itself, but things they induce in us by means of the "size, shape, texture, and motion of their imperceptible parts", or their atoms.[15] The bodies send insensible particles to our senses which let us perceive the object through different faculties; what we perceive is based on the object's composition. With these qualities, people can achieve the object through bringing "co-existing powers and sensible qualities to a common ground for explanation".[17] Locke supposes that one wants to know what "binds these qualities" into an object, and argues that a "substratum" or "substance" has this effect, defining "substance" as follows:

The idea that we have, to which we give the general name substance, being nothing but the supposed, but unknown, support of those qualities we find existing, which we imagine cannot subsist sine re substante, without something to support them, we call that support substantia; which, according to the true import of the word, is, in plain English, standing under or upholding.

— John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding; book 2, chapter 23; "Of our Complex Ideas of Substances"

This substratum is a construct of the mind in an attempt to bind all the qualities seen together; it is only "a supposition of an unknown support of qualities that are able to cause simple ideas in us".[15] Without making a substratum, people would be at a loss as to how different qualities relate. Locke does, however, mention that this substratum is an unknown, relating it to the story of the world on the turtle's back and how the believers eventually had to concede that the turtle just rested on "something he knew not what".[15] This is how the mind perceives all things and from which it can make ideas about them; it is entirely relative, but it does provide a "regularity and consistency to our ideas".[16] Substance, overall, has two sets of qualities that define it, and how we perceive it. These qualities rush to our minds which must organize them. As a result, it creates a substratum for each object to which it groups related qualities.

Irreducible concepts[edit]

Two irreducible concepts encountered in substance theory are the bare particular and inherence.

Bare particular[edit]

In substance theory, a bare particular of an object is the element without which the object would not exist, that is, its substance, which exists independently from its properties, even if it is impossible for it to lack properties entirely. It is "bare" because it is considered without its properties and "particular" because it is not abstract. The properties that the substance has are said to inhere in the substance.

Inherence[edit]

Another primitive concept in substance theory is the inherence of properties within a substance. For example, in the sentence, "The apple is red" substance theory says that red inheres in the apple. Substance theory takes the meaning of an apple having the property of redness to be understood, and likewise that of a property's inherence in substance, which is similar to, but not identical with, being part of the substance.

The inverse relation is participation. Thus in the example above, just as red inheres in the apple, so the apple participates in red.

Arguments supporting the theory[edit]

Two common arguments supporting substance theory are the argument from grammar and the argument from conception.

Argument from grammar[edit]

The argument from grammar uses traditional grammar to support substance theory. For example, the sentence "Snow is white" contains a grammatical subject "snow" and the predicate "is white", thereby asserting snow is white. The argument holds that it makes no grammatical sense to speak of "whiteness" disembodied, without asserting that snow or something else is white. Meaningful assertions are formed by virtue of a grammatical subject, of which properties may be predicated, and in substance theory, such assertions are made with regard to a substance.

Bundle theory rejects the argument from grammar on the basis that a grammatical subject does not necessarily refer to a metaphysical subject. Bundle theory, for example, maintains that the grammatical subject of statement refers to its properties. For example, a bundle theorist understands the grammatical subject of the sentence, "Snow is white", to be a bundle of properties such as white. Accordingly, one can make meaningful statements about bodies without referring to substances.

Argument from conception[edit]

Another argument for the substance theory is the argument from conception. The argument claims that in order to conceive of an object's properties, like the redness of an apple, one must conceive of the object that has those properties. According to the argument, one cannot conceive of redness, or any other property, distinct from the substance that has that property.

Criticism[edit]

The idea of substance was famously critiqued by David Hume,[18][citation needed] who held that since substance cannot be perceived, it should not be assumed to exist. But the claim that substance cannot be perceived is neither clear nor obvious, and neither is the implication obvious.[according to whom?]

Friedrich Nietzsche, and after him Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze also rejected the notion of "substance", and in the same movement the concept of subject - seeing both concepts as holdovers from Platonic idealism. For this reason, Althusser's "anti-humanism" and Foucault's statements were criticized, by Jürgen Habermas and others, for misunderstanding that this led to a fatalist conception of social determinism. For Habermas, only a subjective form of liberty could be conceived, to the contrary of Deleuze who talks about "a life", as an impersonal and immanent form of liberty.

For Heidegger, Descartes means by "substance" that by which "we can understand nothing else than an entity which is in such a way that it need no other entity in order to be." Therefore, only God is a substance as Ens perfectissimus (most perfect being). Heidegger showed the inextricable relationship between the concept of substance and of subject, which explains why, instead of talking about "man" or "humankind", he speaks about the Dasein, which is not a simple subject, nor a substance.[19]

Alfred North Whitehead has argued that the concept of substance has only a limited applicability in everyday life and that metaphysics should rely upon the concept of process.[20]

Roman Catholic theologian Karl Rahner, as part of his critique of transubstantiation, rejected substance theory and instead proposed the doctrine of transfinalization, which he felt was more attuned to modern philosophy. However, this doctrine was rejected by Pope Paul VI in his encyclical Mysterium fidei.

Bundle theory[edit]

In direct opposition to substance theory is bundle theory, whose most basic premise is that all concrete particulars are merely constructions or 'bundles' of attributes or qualitative properties:

- Necessarily, for any concrete entity, , if for any entity, , is a constituent of , then is an attribute.[21]

The bundle theorist's principal objections to substance theory concern the bare particulars of a substance, which substance theory considers independently of the substance's properties. The bundle theorist objects to the notion of a thing with no properties, claiming that such a thing is inconceivable and citing John Locke, who described a substance as "a something, I know not what." To the bundle theorist, as soon as one has any notion of a substance in mind, a property accompanies that notion.

Identity of indiscernibles counterargument[edit]

The indiscernibility argument from the substance theorist targets those bundle theorists who are also metaphysical realists. Metaphysical realism uses the identity of universals to compare and identify particulars. Substance theorists say that bundle theory is incompatible with metaphysical realism due to the identity of indiscernibles: particulars may differ from one another only with respect to their attributes or relations.

The substance theorist's indiscernibility argument against the metaphysically realistic bundle theorist states that numerically different concrete particulars are discernible from the self-same concrete particular only by virtue of qualitatively different attributes.

- Necessarily, for any complex objects, and , if for any entity, , is a constituent of if and only if is a constituent of , then is numerically identical with .[21]

The indiscernibility argument points out that if bundle theory and discernible concrete particulars theory explain the relationship between attributes, then the identity of indiscernibles theory must also be true:

- Necessarily, for any concrete objects, and , if for any attribute, Φ, Φ is an attribute of if and only if Φ is an attribute of , then is numerically identical with .[21]

The indiscernibles argument then asserts that the identity of indiscernibles is violated, for example, by identical sheets of paper. All of their qualitative properties are the same (e.g. white, rectangular, 9 x 11 inches...) and thus, the argument claims, bundle theory and metaphysical realism cannot both be correct.

However, bundle theory combined with trope theory (as opposed to metaphysical realism) avoids the indiscernibles argument because each attribute is a trope if can only be held by only one concrete particular.

The argument does not consider whether "position" should be considered an attribute or relation. It is after all through the differing positions that we in practice differentiate between otherwise identical pieces of paper.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Rae Langton (2001). Kantian humility: our ignorance of things in themselves. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-19-924317-4.

- ^ Ackrill, J.L. (1988). A New Aristotle Reader. Princeton University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781400835829.

- ^ Aristotle's Categories (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ Neoplatonism (Ancient Philosophies) by Pauliina Remes (2008), University of California Press ISBN 0520258347, pages 48–52.

- ^ Millican, Peter (2015). "Locke on Substance and Our Ideas of Substances". In Paul Lodge; Tom Stoneham. Locke and Leibniz on Substance. Routledge. pp. 8–27.

- ^ Jones, Jan-Erik. "Locke on Real Essence". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Dunn, John (2003). Locke: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jones, Jan-Erik (July 2016). "Locke On Real Essence". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Atherton, Margaret (1999). The Empiricists: Critical Essays on Locke, Berkely, and Hume. Rowman and Littlefield.

- ^ Locke, John (1959). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Dover Publications.

- ^ Millican, Peter (2015). "Locke on Substance and Our Ideas of Substances". In Paul Lodge; Tom Stoneham. Locke and Leibniz on Substance. Routledge. pp. 8–27.

- ^ Jones, Jan-Erik. "Locke on Real Essence". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Garret, Jan (February 27, 2004). "A Lockean Glossary". A Lockean Glossary.

- ^ a b Sheridan, P. (2010). Locke: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum. pp. 34, 38.

- ^ a b c d e Locke, J. (1979). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book II (P. H. Nidditch, Ed.). Clarendon: Oxford.

- ^ a b Stumpf, S. E. (1999). Socrates to Sartre: a history of philosophy. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. p. 260.

- ^ Constantin, Ion, PhD.C., I.F.P.C.R.M. (2012). Philosophy of Substance: A Historical Perspective. Linguistic and Philosophical Investigations, 11, 135-140. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1030745650

- ^ Hockney, Mike (2015). The Forbidden History of Science. Hyperreality Books.

- ^ A. Kadir Cucen (2002-01-18). "Heidegger's Critique of Descartes' Metaphysics" (PDF). Uludag University. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ See, e.g., Ronny Desmet and Michel Weber (edited by), Whitehead. The Algebra of Metaphysics. Applied Process Metaphysics Summer Institute Memorandum, Louvain-la-Neuve, Éditions Chromatika, 2010 (ISBN 978-2-930517-08-7).

- ^ a b c Loux, M.J. (2002). Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction. Routledge Contemporary Introductions to Philosophy Series. Taylor & Francis. pp. 106–107, 110. ISBN 9780415140348. LCCN 97011036.

External links[edit]

- Robinson, Howard. "Substance". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Robinson, Tad. "17th Century Theories of Substance". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Friesian School on Substance and Essence