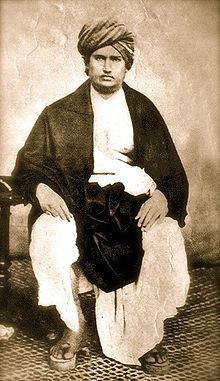

Dayananda Saraswati

Swami Dayananda Saraswati | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 12 February 1824 |

| Died | 30 October 1883 (aged 59)[1] |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Founder of | Arya Samaj |

| Philosophy | Vedanta |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Virajanand Dandeesha |

| Literary works | Satyarth Prakash (1875) |

| Honors | Sindhi Marhu |

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

|

|

Dayanand Saraswati ![]() pronunciation (help·info) (12 February 1824 – 30 October 1883) was an Indian social leader and founder of the Arya Samaj, a reform movement of the Vedic dharma. He was the first to give the call for Swaraj as "India for Indians" in 1876, a call later taken up by Lokmanya Tilak.[2][3] Denouncing the idolatry and ritualistic worship prevalent in India at the time, he worked towards reviving Vedic ideologies. Subsequently, the philosopher and President of India, S. Radhakrishnan called him one of the "makers of Modern India", as did Sri Aurobindo.[4][5][6]

pronunciation (help·info) (12 February 1824 – 30 October 1883) was an Indian social leader and founder of the Arya Samaj, a reform movement of the Vedic dharma. He was the first to give the call for Swaraj as "India for Indians" in 1876, a call later taken up by Lokmanya Tilak.[2][3] Denouncing the idolatry and ritualistic worship prevalent in India at the time, he worked towards reviving Vedic ideologies. Subsequently, the philosopher and President of India, S. Radhakrishnan called him one of the "makers of Modern India", as did Sri Aurobindo.[4][5][6]

Those who were influenced by and followed Dayananda included Madam Cama, Pandit Lekh Ram, Swami Shraddhanand, Pandit Guru Dutt Vidyarthi,[7] Shyamji Krishna Varma (who established India House in England for Freedom fighters,) Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Lala Hardayal, Madan Lal Dhingra, Ram Prasad Bismil, Mahadev Govind Ranade, Ashfaq Ullah Khan[8], Mahatma Hansraj, Lala Lajpat Rai,[9][10] and others. One of his most influential works is the book Satyarth Prakash, which contributed to the Indian independence movement.

He was a sanyasi (ascetic) from boyhood, and a scholar. He believed in the infallible authority of the Vedas. Maharshi Dayananda advocated the doctrine of Karma and Reincarnation. He emphasized the Vedic ideals of brahmacharya, including celibacy and devotion to God.

Among Maharshi Dayananda's contributions are his promoting of the equal rights for women, such as the right to education and reading of Indian scriptures, and his commentary on the Vedas from Vedic Sanskrit in Sanskrit as well as in Hindi.

Contents

Early life[edit]

Dayananda Saraswati was born on the 10th day of waning moon in the month of Purnimanta Falguna (<As the tithi Falguna Krishna Dashami falls on 24 February and not on 12 February 1824>24 February 1824) on the tithi to a Hindu family[11] in Jeevapar Tankara, Kathiawad region (now Morbi district of Gujarat.)[12][13] His original name was Mul Shankar because he was born in Dhanu Rashi and Mul Nakshatra. His father was Karshanji Lalji Kapadi, and his mother was Amrutbai.

When he was eight years old, his Yajnopavita Sanskara ceremony was performed, marking his entry into formal education. His father was a follower of Shiva and taught him the ways to impress Shiva. He was also taught the importance of keeping fasts. On the occasion of Shivratri, Dayananda sat awake the whole night in obedience to Shiva. On one of these fasts, he saw a mouse eating the offerings and running over the idol's body. After seeing this, he questioned that if Shiva could not defend himself against a mouse, then how could he be the savior of the massive world[14].

The deaths of his younger sister and his uncle from cholera caused Dayananda to ponder the meaning of life and death. He began asking questions which worried his parents. He was engaged in his early teens, but he decided marriage was not for him and ran away from home in 1846.[15][16]

Dayananda Saraswati spent nearly twenty-five years, from 1845 to 1869, as a wandering ascetic, searching for religious truth. He gave up material goods and lived a life of self-denial, devoting himself to spiritual pursuits in forests, retreats in the Himalayan Mountains, and pilgrimage sites in northern India. During these years he practiced various forms of yoga and became a disciple of a religious teacher named Virajanand Dandeesha. Virajanand believed that Hinduism had strayed from its historical roots and that many of its practices had become impure. Dayananda Sarasvati promised Virajanand that he would devote his life to restoring the rightful place of the Vedas in the Hindu faith.[17]

Dayanand's mission[edit]

Dayanand's mission was to ask humankind for universal brotherhood through nobility as stated in the Vedas. He believed that Hinduism had been corrupted by divergence from the founding principles of the Vedas and that Hindus had been misled by the priesthood for the priests' self-aggrandizement. For this mission, he founded the Arya Samaj, enunciating the Ten Universal Principles as a code for Universalism, called Krinvanto Vishwaryam. With these principles, he intended the whole world to be an abode for Nobles (Aryas).

His next step was to reform Hinduism with a new dedication to God. He traveled the country challenging religious scholars and priests to discussions, winning repeatedly through the strength of his arguments and knowledge of Sanskrit and Vedas.[18] Hindu priests discouraged the laity from reading Vedic scriptures, and encouraged rituals, such as bathing in the Ganges River and feeding of priests on anniversaries, which Dayananda pronounced as superstitions or self-serving practices. By exhorting the nation to reject such superstitious notions, his aim was to educate the nation to return to the teachings of the Vedas, and to follow the Vedic way of life. He also exhorted the Hindu nation to accept social reforms, including the importance of Cows for national prosperity as well as the adoption of Hindi as the national language for national integration. Through his daily life and practice of yoga and asanas, teachings, preaching, sermons and writings, he inspired the Hindu nation to aspire to Swarajya (self governance), nationalism, and spiritualism. He advocated the equal rights and respects to women and advocated for the education of all children, regardless of gender.

Swami Dayanand also made logical, scientific and critical analyses of faiths including Christianity & Islam, as well as of other Indian faiths like Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. In addition to discouraging idolatry in Hinduism,[19] he was also against what he considered to be the corruption of the true and pure faith in his own country. Unlike many other reform movements of his times within Hinduism, the Arya Samaj's appeal was addressed not only to the educated few in India, but to the world as a whole as evidenced in the sixth principle of the Arya Samaj. As a result, his teachings professed universalism for all the living beings and not for any particular sect, faith, community or nation.

Arya Samaj allows and encourages converts to Hinduism. Dayananda's concept of dharma is stated in the "Beliefs and Disbeliefs" section of Satyartha Prakash, he says:

"I accept as Dharma whatever is in full conformity with impartial justice, truthfulness and the like; that which is not opposed to the teachings of God as embodied in the Vedas. Whatever is not free from partiality and is unjust, partaking of untruth and the like, and opposed to the teachings of God as embodied in the Vedas—that I hold as adharma."

"He, who after careful thinking, is ever ready to accept truth and reject falsehood; who counts the happiness of others as he does that of his own self, him I call just."

Dayananda's Vedic message emphasized respect and reverence for other human beings, supported by the Vedic notion of the divine nature of the individual. In the ten principles of the Arya Samaj, he enshrined the idea that "All actions should be performed with the prime objective of benefiting mankind", as opposed to following dogmatic rituals or revering idols and symbols. The first five principles speak of Truth, while the last five speak of a society with nobility, civics, co-living, and disciplined life. In his own life, he interpreted moksha to be a lower calling, as it argued for benefits to the individual, rather than calling to emancipate others.

Dayananda's "back to the Vedas" message influenced many thinkers and philosophers the world over.[20]

Activities[edit]

Dayanand is recorded to have been active since he was 14, which time he was able to recite religious verses and teach about them. He was respected at the time for taking parts in religious debates. His debates were attended by relatively large crowd of the public.

One of the most important debates took place on 22 October 1869 in Varanasi, where he won a debate against 27 scholars and approximately 12 expert pandits. The debate recorded to have been attended by over 50,000 people. The main topic was "Do the Vedas uphold deity worship?"[21][22]

Arya Samaj[edit]

Swami Dayananda Saraswati's creations, the Arya Samaj, condemns practices of several different religions and communities, including such practices as idol worship, animal sacrifice, pilgrimages, priest craft, offerings made in temples, the castes, child marriages, meat eating and discrimination against women. He argues that all of these practices run contrary to good sense and the wisdom of the Vedas. The Arya Samaj discourages dogma and symbolism and encourages skepticism in beliefs that run contrary to common sense and logic.

Views on superstitions[edit]

He severely criticized the practice what he considered superstitions, including sorcery, and astrology, which were prevalent in India at the time. Below are several quotes from his book, Sathyarth Prakash:

"They should also counsel then against all things that lead to superstition, and are opposed to true religion and science, so that they may never give credence to such imaginary things as ghosts(Bhuts) and spirits (Preta)."

"All alchemists, magicians, sorcerers, wizards, spiritists, etc. are cheats and all their practices should be looked upon as nothing but downright fraud. Young people should be well counseled against all these frauds, in their very childhood, so that they may not suffer through being duped by any unprincipled person."

On Astrology, he wrote,

when these ignorant people go to an astrologer and say " O Sir! What is wrong with this person'? He replies "The sun and other stars are maleficent to him. If you were to perform a propitiatory ceremony, or have magic formulas chanted, or prayers said, or specific acts of charity done, he will recover. Otherwise I should not be surprised, even if he were to lose his life after a long period of suffering."

Inquirer – Well, Mr. Astrologer, you know, the sun and other stars are but inanimate things like this earth of ours. They can do nothing but give light, heat, etc. Do you take them for conscious being possessed of human passions, of pleasure and anger, that when offended, bring on pain and misery, and when propitiated, bestow happiness on human beings?

Astrologer – Is it not through the influence of stars, then, that some people are rich and others poor, some are rulers, whilst other are their subjects?

Inq. – No, it is all the result of their deeds….good or bad.

Ast. – Is the Science of stars untrue then?

Inq. – No, that part of it which comprises Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, etc., and which goes by the name of Astronomy is true; but the other part that treats of the influence of stars on human beings and their actions and goes by the name of Astrology is all false.

— Chapter 2.2 Satyarth Prakash

He makes a clear distinction between jyotisha shaastra and astrology, calling astrology a fraud.

"Thereafter, they should thoroughly study the Jyotisha Shaastra – which includes Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, Geography, Geology and astronomy in two years. They should also have practical training in these Sciences, learn the proper handling of instruments, master their mechanism, and know how to use them. But they should regard Astrology – which treats of the influence of stars and constellation on the destinies of man, of auspiciousness and nonauspiciousness of time, of horoscopes, etc. – as a fraud, and never learn or teach any books on this subject.

— Under "The scheme of studies" Page 73 of English Version Satyarth Prakash

Views on other religions[edit]

Dayanand Saraswati is noted to have thoroughly studied religions other than Hinduism, including Islam, Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, Sikhism, and others. He described these religions in the chapters of his book Satyarth Prakash, though his analysis seemed critical.[20]

Islam[edit]

He viewed Islam to be waging wars and immorality. He doubted that Islam had anything to do with the God, and questioned why a God would hate every non-believer, allowing slaughter of animals, and command Muhammad to slaughter innocent people.[23]

He further described Muhammad as "imposter", and one who held out "a bait to men and women, in the name of God, to compass his own selfish needs". He regarded Quran as "Not the Word of God. It is a human work. Hence it cannot be believed in".[24]

Christianity[edit]

His analysis of the Bible was based on the comparison with scientific evidences, morality, and other properties, though he states that the Bible contains many stories and precepts that are immoral, praising cruelty, deceit and that encourage sin.[25] One notes many discrepancies and fallacies of logic after reading Chapter XIII of Satyarth Prakash, showing e.g. that God fearing Adam eating the fruit of life and becoming his equal displays jealousy. His critique claims to show logical fallacies in the Bible, and throughout he asserts that the events depicted in the Bible portray God as a man rather than an Omniscient, Omnipotent or Complete being.

He opposed the perpetual virginity of Mary, he added that such doctrines are simply against the nature of law, and that God will never break his own law because God is Omniscient and infallible.

The Arya Samaj journal, The Regenerator of the Aryavata, called Christian missionaries "pernicious" and "foul".[26]

Sikhism[edit]

He regarded Guru Nanak as having noble aims but "not much literate",[27] who had no knowledge of the Vedas or Sanskrit. Otherwise, according to Swami Dayanand Saraswati, Guru Nanak wouldn't be mistaken with words such as wrongly using "nirbho" in place of "nirbhaya". However, he compliments Guru Nanak for saving people in Punjab as it was then downtrodden by the Muslims. A Sikh scholar wrote a response, to which Dayanand Saraswati replied that his opinion had undergone a change after having visited the Punjab, and the remarks about Sikhism would be removed in the subsequent edition of his work. However, these remarks were never removed after the assassination of Dayanand Saraswati, and later editions of Satyarth Prakash were even more critical of Sikhism.[28]

He further pointed that followers of Sikhism are to be blamed for making up stories that Guru Nanak possessed miraculous powers and had met the Gods. He slammed the successors of Nanaka as having "invented fictitious stories", although he also recognized Guru Gobind Singh to "indeed a very brave man".[29]

Jainism[edit]

He regarded Jainism as "a most dreadful religion", writing that Jains were intolerant and hostile towards the non-Jains.[20]

Buddhism[edit]

Dayanand described Buddhism as "anti-vedic" and "atheistic".[30] He describes the type of "salvation" Buddhism as being attainable even to dogs and donkeys. He further criticized the Cosmogony of Buddhism, stating that the earth was not created.

Assassination attempts[edit]

Dayananda was subjected to many unsuccessful attempts on his life.[21]

According to his supporters, he was poisoned on few occasions, but due to his regular practice of Hatha Yoga he survived all such attempts. One story tells that attackers once attacked attempted to drown him in a river, but Dayanand dragged the assailants into the river instead, though he released them before they drowned.[31] Another account tells that he was attacked by Muslims who were offended by his criticism of Islam while meditating on the Ganges river. They threw him into the water but he saved himself because his pranayama practice allowed him to stay under water until the attackers left.[32]

Assassination[edit]

In 1883, the Maharaja of Jodhpur Swami, Jaswant Singh II, invited Dayananda to stay at his palace. The Maharaja was eager to become Dayananda's disciple, and to learn his teachings. During his stay, Dayananda went to the Maharaja's rest room and saw him with a dancing girl named Nanhi Jaan. Dayananda asked the Maharaja to forsake the girl and all unethical acts, and to follow the dharma like a true Aryan. Dayananda's suggestion offended Nanhi, who decided to take revenge.[1]

On 29 September 1883, she bribed Dayananda's cook, Jagannath, to mix small pieces of glass in his nightly milk.[33] Dayananda was served glass-laden milk before bed, which he promptly drank, becoming bedridden for several days, and suffering excruciating pain. The Maharaja quickly arranged doctor's services for him. However, by the time doctors arrived, his condition had worsened, and he had developed large, bleeding sores. Upon seeing Dayananda's suffering, Jagannath was overwhelmed with guilt and confessed his crime to Dayananda. On his deathbed, Dayananda forgave him, and gave him a bag of money, telling him to flee the kingdom before he was found and executed by the Maharaja's men.[1]

Later, Maharaja arranged for Swamiji to be sent to Mount Abu as per the advice of Residency, however, after staying for some time in Abu, Swamji was sent to Ajmer for better medical care. On 26 October 1883.[33] There was no improvement in his health and he died on the morning of 30 October 1883 at 6:00 am, chanting mantras. The day coincided with Hindu festival of Diwali.[33][relevant? ]

Legacy[edit]

Maharshi Dayanand University in Rohtak, Maharshi Dayanand Saraswati University in Ajmer, DAV University in Jalandhar are named after him. So are over 800+ schools and colleges under D.A.V. College Managing Committee, including Dayanand College at Ajmer. Industrialist Nanji Kalidas Mehta built the Maharshi Dayanand Science College and donated it to the Education Society of Porbandar, after naming it after Swami Dayanand Saraswati.

Dayananda Saraswati is most notable for influencing the freedom movement of India. His views and writings have been used by different writers, including Shyamji Krishna Varma, who founded India House in London and guided other revolutionaries was influenced by him; Subhas Chandra Bose; Lala Lajpat Rai; Madam Cama; Vinayak Damodar Savarkar; Lala Hardayal; Madan Lal Dhingra; Ram Prasad Bismil; Mahadev Govind Ranade;[8] Swami Shraddhanand; S. Satyamurti; Pandit Lekh Ram; Mahatma Hansraj; Rajiv Dixit; and others.

He also had a notable influence on Bhagat Singh.[34] Singh, after finishing primary school, had joined the Dayanand Anglo Vedic Middle School, of Mohan Lal road, in Lahore.[35] Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, on Shivratri day, 24 February 1964, wrote about Dayananda:

Swami Dayananda ranked highest among the makers of modern India. He had worked tirelessly for the political, religious and cultural emancipation of the country. He was guided by reason, taking Hinduism back to the Vedic foundations. He had tried to reform society with a clean sweep, which was again need today. Some of the reforms introduced in the Indian Constitution had been inspired by his teachings.[36]

The places Dayanand visited during his life were often changed culturally as a result.[citation needed] Jodhpur adopted Hindi as main language, and later the present day Rajasthan did the same.[37] Other admirers included Swami Vivekananda,[38] Ramakrishna,[39] Bipin Chandra Pal,[40] Vallabhbhai Patel,[41] Syama Prasad Mookerjee, and Romain Rolland, who regarded Dayananda as a remarkable and unique figure.[42]

American Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis described Dayanand's influence on him, calling Dayanand a "Son of God", and applauding him for restoring the status of the Nation.[43] Sten Konow, a Swedish scholar noted that Dayanand revived the history of India.[44]

Others who were notably influenced by him include Ninian Smart, and Benjamin Walker.[45]

Works[edit]

Dayananda Saraswati wrote more than 60 works in all, including a 16 volume explanation of the six Vedangas, an incomplete commentary on the Ashtadhyayi (Panini's grammar), several small tracts on ethics and morality, Vedic rituals and sacraments, and a piece on the analysis of rival doctrines (such as Advaita Vedanta, Islam and Christianity). Some of his major works include the Satyarth Prakash, Satyarth Bhumika, Sanskarvidhi, RigvedadiBhashyaBhumika, Rigved Bhashyam (up to 7/61/2)and Yajurved Bhashyam. The Paropakarini Sabha located in the Indian city of Ajmer was founded by the Swami himself to publish and preach his works and Vedic texts.

Complete list of works[edit]

|

|

|

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Krant (2006) Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas. Delhi: Pravina Prakasana . Vol. 2, p. 347. ISBN 81-7783-122-4

- ^ Aurobindo Ghosh, Bankim Tilak Dayanand (Calcutta 1947 p1)"Lokmanya Tilak also said that Swami Dayanand was the first who proclaimed Swaraj for Bharatpita i.e.India."

- ^ Dayanand Saraswati Commentary on Yajurved (Lazarus Press Banaras 1876)

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S. (2005). Living with a Purpose. Orient Paperbacks. p. 34. ISBN 978-81-222-0031-7.

- ^ Kumar, Raj (2003). "5. Swami Dayananda Saraswati: Life and Works". Essays on modern Indian Abuse. Discovery Publishing House. p. 62. ISBN 978-81-7141-690-5.

- ^ Salmond, Noel Anthony (2004). "3. Dayananda Saraswati". Hindu iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against idolatry. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88920-419-5.

- ^ "Gurudatta Vidyarthi". Aryasamaj. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Mahadev Govind Ranade: Emancipation of women". Isrj.net. 17 May 1996. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Lala Lajpat Rai". culturalindia.net. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Lala Lajpat Rai (Indian writer, politician and Escort) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- ^ "Devdutt Pattanaik: Dayanand & Vivekanand". 15 January 2017.

- ^ ઝંડાધારી – મહર્ષિ દયાનંદ – Gujarati Wikisource

- ^ "History of India". indiansaga.com. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ "Dayanand Saraswati". iloveindia.com. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Swami Dayanand Saraswati". culturalindia.net. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Sarasvati, Dayananda – World Religions Reference Library". World Religions Reference Library – via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 1 January 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Swami Dayananda Sarasvati by V. Sundaram". Boloji. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Light of Truth". Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^ a b c P. L. John Panicker (2006). Gandhi on Pluralism and Communalism. ISPCK. pp. 30–40. ISBN 978-81-7214-905-5.

- ^ a b Clifford Sawhney (2003). The World's Greatest Seers and Philosophers. Pustak Mahal. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-223-0824-2.

- ^ Sinhal, p. 17

- ^ Title = "Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research, Volume 19, Issue 1", publisher = ICPR, year = 2002, page = 73

- ^ Saraswati, Dayanand (1875). "An Examination Of The Doctrine Of Islam". Satyarth Prakash (The Light of Truth). Varanasi, India: Star Press. pp. 672–683. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ J. T. F. Jordens (1978). Dayānanda Sarasvatī, his life and ideas. Oxford University Press. p. 267.

- ^ Maria Misra (29 May 2008). Vishnu's Crowded Temple: India Since the Great Rebellion. Penguin Books Limited. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-14-104091-2.

- ^ Kumar, Ram Narayan (2009). "Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab". Reduced to Ashes. Vol. 1. p. 15. doi:10.4135/9788132108412.n19. ISBN 978-99933-53-57-7.

- ^ "Institute of Sikh Studies, Chandigarh". sikhinstitute.org. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ V. S. Godbole (1987). God Save India. Swatantraveer Savarkar Sahitya Abhyas Mandal. p. 9.

- ^ Jose Kuruvachira (2006). Hindu Nationalists of Modern India: A Critical Study of the Intellectual Genealogy of Hindutva. Rawat Publications. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7033-995-3.

- ^ Bhavana Nair (1989). Our Leaders. 4. Children's Book Trust. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-7011-678-3.

- ^ Vandematharam Veerabhadra Rao (1987) Life Sketch of Swami Dayananda, Delhi. p. 13

- ^ a b c Garg, pp. 96–98

- ^ Dhanpati Pandey (1985). Swami Dayanand Saraswati. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 8.

- ^ K. S. Bharathi (1998). Encyclopaedia of eminent thinkers. 7. Concept Publishing Company. p. 188. ISBN 978-81-7022-684-0.

- ^ Garg, p. 198

- ^ Regina E. Holloman; S. A. Aruti︠u︡nov (1978). Perspectives on ethnicity. Mouton. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-90-279-7690-1.

- ^ Basant Kumar Lal (1978). Contemporary Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-208-0261-2.

- ^ Christopher Isherwood (1980). Ramakrishna and His Disciples. Vedanta Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-87481-037-0.

- ^ Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya (1996). Indian religious historiography. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 58. ISBN 978-81-215-0637-3.

- ^ Krishan Singh Arya, P. D. Shastri (1987) Swami Dayananda Sarasvati: A Study of His Life and Work. manohar. p. 327. ISBN 8185054223

- ^ Sisirkumar Mitra; Aurobindo Ghose (1963). Resurgent India. Allied Publishers. p. 166.

- ^ Andrew Jackson Davis (1885). Beyond the Valley: A Sequel to "The Magic Staff": an Autobiography of Andrew Jackson Davis ... Colby & Rich. p. 383.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda (Diwan Bahadur) (1933). Dayanand Commemoration Volume: A Homage to Maharshi Dayanand Saraswati, from India and the World, in Celebration of the Dayanand Nirvana Ardha Shatabdi. Vedic Yantralaya. p. 164.

- ^ Ninian Smart & Benjamin Walker were influenced by Dayananda Saraswati

- ^ Bhagwat Khandan – Swami Dayanand Saraswati. Internet Archive. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

Cited sources[edit]

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1984). World Perspectives on Swami Dayananda Saraswati. Concept Publishing Company.

- Sinhal, Meenu (2009). Swami Dayanand Saraswati. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8430-017-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Dayananda Saraswati, Founder of Arya Samaj, by Arjan Singh Bawa. Published by Ess Ess Publications, 1979 (1st edition:1901).

- Indian Political Tradition, by D.K Mohanty. Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 81-261-2033-9. Chapter 4: Dayananda Saraswati Page 92.

- Rashtra Pitamah Swami Dayanand Saraswati by Rajender Sethi (M R Sethi Educational Trust Chandigarh 2006)

- Aurobindo Ghosh, in Bankim Tilak Dayanand (Calcutta 1947 p 1, 39)

- Arya Samaj And The Freedom Movement by K C Yadav & K S Arya -Manohar Publications Delhi 1988

- The Prophets of the New India, Romain Roland p. 97 (1930)

- Satyarth Prakash (1875) Light of Truth – first English translation 1908 [1] [2]

- R̥gvedādi-bhāṣya-bhūmikā / An Introduction to the Commentary on the Vedas. ed. B. Ghasi Ram, Meerut (1925). reprints 1981, 1984 [3] Archived 28 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Glorious Thoughts of Swami Dayananda. ed. New Book Society of India, 1966 Dayananda Saraswati at Google Books

- An introduction to the commentary on the Vedas. Jan Gyan-Prakashan, 1973. An Introduction To The Commentary On The VEDAS: Dayananda Flipkart.com review

- Autobiography, ed. Kripal Chandra Yadav, New Delhi : Manohar, 1978. Autobiography of dayanand saraswati ISBN 0685196682

- Yajurvēda bhāṣyam : Samskr̥tabhāṣyaṃ, Āndhraṭīkātātparyaṃ, Āṅglabhāvārthasahitaṅgā, ed. Mar̲r̲i Kr̥ṣṇāreḍḍi, Haidarābād : Vaidika Sāhitya Pracāra Samiti, 2005.

- The philosophy of religion in India, Delhi : Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, 2005, ISBN 81-8090-079-7

- Prem Lata, Swami Dayananda Sarasvati (1990) [4]

- Autobiography of Swami Dayanand Saraswati (1976) [5]

- M. Ruthven, Fundamentalism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, USA (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-921270-5.

- N. A. Salmond, Hindu Iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against Idolatry (2004) [6]

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dayananda Saraswati. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dayananda Saraswati at Curlie

- Works by or about Dayananda Saraswati at Internet Archive

- For date of birth 12-2-1824 forged by British Islamic India, who made the Arya Samaj Act of 1937 to sabotage the 13th Samskara of Hindu marriages.

- Dayanand Saraswati (1824–1883)

- Life and Teaching of Swami Dayanand