Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin | |

|---|---|

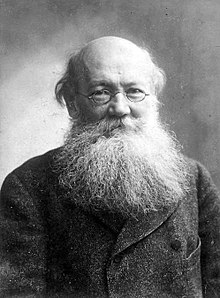

Kropotkin c. 1900 (aged 57) | |

| Born | Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin December 9, 1842 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | February 8, 1921 (aged 78) |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University (no degree)[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Sofia Ananyeva-Rabinovich |

| Era | |

| Region | |

| School | Anarcho-communism |

Main interests |

|

Notable ideas |

|

| Signature | |

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (/kroʊˈpɒtkɪn/;[10] Russian: Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин; December 9, 1842 – February 8, 1921) was a Russian activist, revolutionary, scientist, geographer[11] and philosopher who advocated anarcho-communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, he attended a military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later. He spent the next 41 years in exile in Switzerland, France (where he was imprisoned for almost four years) and in England. He controversially supported the war against Germany,[12][13] and he returned to Russia after the Russian Revolution in 1917, but was disappointed by the Bolshevik form of state socialism.

Kropotkin was a proponent of a decentralised communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations of self-governing communities and worker-run enterprises. He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops; and his principal scientific offering, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. He also contributed the article on anarchism to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition[14] and left unfinished a work on anarchist ethical philosophy.

Contents

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Kropotkin was born in Moscow, into the second-highest level of the Russian aristocracy. His mother was the daughter of a Cossack general.[15] His father, Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, was a prince in Smolensk,[16] of the Rurik dynasty which had ruled Russia before the rise of the Romanovs. Kropotkin's father owned large tracts of land and nearly 1,200 male serfs in three provinces.[15]

"[U]nder the influence of republican teachings", Kropotkin dropped his princely title at age 12, and "even rebuked his friends, when they so referred to him."[17]

In 1857, at age 14, Kropotkin enrolled in the Corps of Pages at St. Petersburg.[18] Only 150 boys – mostly children of nobility belonging to the court – were educated in this privileged corps, which combined the character of a military school endowed with special rights and of a court institution attached to the Imperial Household. Kropotkin's memoirs detail the hazing and other abuse of pages for which the Corps had become notorious.[19]

In Moscow, Kropotkin developed what would become a lifelong interest in the condition of the peasantry. Although his work as a page for Tsar Alexander II made Kropotkin skeptical about the tsar's "liberal" reputation,[20] Kropotkin was greatly pleased by the tsar's decision to emancipate the serfs in 1861.[21] In St. Petersburg, he read widely on his own account, and gave special attention to the works of the French encyclopædists and to French history. The years 1857–1861 witnessed a growth in the intellectual forces of Russia, and Kropotkin came under the influence of the new liberal-revolutionary literature, which largely expressed his own aspirations.[22]

In 1862, Kropotkin graduated first in his class from the Corps of Pages, and entered the Tsarist army.[23] The members of the corps had the prescriptive right to choose the regiment to which they would be attached. Following a desire to "be someone useful", Kropotkin chose the difficult route of serving in a Cossack regiment in eastern Siberia.[23] For some time, he was aide de camp to the governor of Transbaikalia at Chita. Later he was appointed attaché for Cossack affairs to the governor-general of East Siberia at Irkutsk.[24]

Geographical expeditions in Siberia[edit]

The administrator under whom Kropotkin served, General Boleslar Kazimirovich Kukel (1829–1869), was a liberal and a democrat who maintained personal connections to various Russian radical political figures exiled to Siberia. These included the writer M. I. Mikhailov (1826–1865), to whom Kukel sent Kropotkin to warn the exiled intellectual that Moscow police agents were on the scene to examine his ongoing political activities in confinement.[25] As a result of this assignment, Kropotkin made the acquaintance of Mikhailov, who provided the young Tsarist functionary with a copy of a book by the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon — Kropotkin's first introduction to anarchist ideas.[25] Kukel was subsequently dismissed from his administrative position and Kropotkin moved from administration to state-sponsored scientific endeavors.[25]

In 1864 Kropotkin accepted a position in a geographical survey expedition, crossing North Manchuria from Transbaikalia to the Amur, and soon was attached to another expedition up the Sungari River into the heart of Manchuria. The expeditions yielded valuable geographical results. The impossibility of obtaining any real administrative reforms in Siberia now induced Kropotkin to devote himself almost entirely to scientific exploration, in which he continued to be highly successful.[26]

Kropotkin continued his political reading, including works by such prominent liberal thinkers as John Stuart Mill and Alexander Herzen. These readings, along with his experiences among peasants in Siberia, led him to declare himself an anarchist by 1872.[27]

In 1867, Kropotkin resigned his commission in the army and returned to St. Petersburg, where he entered the Saint Petersburg Imperial University to study mathematics, becoming at the same time secretary to the geography section of the Russian Geographical Society.[28] His departure from a family tradition of military service prompted his father to disinherit him, "leaving him a 'prince' with no visible means of support".[29]

In 1871, Kropotkin explored the glacial deposits of Finland and Sweden for the Society.[28] In 1873, he published an important contribution to science, a map and paper in which he showed that the existing maps entirely misrepresented the physical features of Asia; the main structural lines were in fact from southwest to northeast, not from north to south or from east to west as had been previously supposed. During this work, he was offered the secretaryship of the Society, but he had decided that it was his duty not to work at fresh discoveries but to aid in diffusing existing knowledge among the people at large. Accordingly, he refused the offer and returned to St. Petersburg, where he joined the revolutionary party.[30]

Activism in Switzerland and France[edit]

Kropotkin visited Switzerland in 1872 and became a member of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) at Geneva. However, he found that he did not like IWA's style of socialism. Instead, he studied the programme of the more radical Jura federation at Neuchâtel and spent time in the company of the leading members, and adopted the creed of anarchism.[31]

Activism in Russia and arrest[edit]

On returning to Russia, Kropotkin's friend Dmitri Klements introduced him to the Circle of Tchaikovsky, a socialist/populist group created in 1872. Kropotkin worked to spread revolutionary propaganda among peasants and workers, and acted as a bridge between the Circle and the aristocracy. Throughout this period, Kropotkin maintained his position within the Geographical Society in order to provide cover for his activities.[32]

In 1872, Kropotkin was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress for subversive political activity, as a result of his work with the Circle of Tchaikovsky. Because of his aristocratic background, he received special privileges in prison, such as permission to continue his geographical work in his cell. He delivered his report on the subject of the Ice Age in 1876, where he argued that it had taken place in not as distant a past as originally thought.[33]

Escape and exile[edit]

In 1876, just before his trial, Kropotkin was moved to a low-security prison in St. Petersburg, from which he escaped with the help of his friends. On the night of the escape, Kropotkin and his friends celebrated by dining in one of the finest restaurants in St. Petersburg, assuming correctly that the police would not think to look for them there. After this, he boarded a boat, and headed to England.[34] After a short stay there, he moved to Switzerland where he joined the Jura Federation. In 1877, he moved to Paris, where he helped start the socialist movement. In 1878, he returned to Switzerland where he edited the Jura Federation's revolutionary newspaper Le Révolté, and published various revolutionary pamphlets.[35]

In 1881, shortly after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, he was expelled from Switzerland. After a short stay at Thonon (Savoy), he stayed in London for nearly a year.[36] He attended the Anarchist Congress in London from July 14, 1881.[37] Other delegates included Marie Le Compte, Errico Malatesta, Saverio Merlino, Louise Michel, Nicholas Tchaikovsky and Émile Gautier. While respecting "complete autonomy of local groups", the congress defined propaganda actions that all could follow and agreed that propaganda by the deed was the path to social revolution.[37] The Radical of July 23, 1881 reported that the congress met on July 18 at the Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy Square, with speeches by Marie Le Compte, "the transatlantic agitator", Louise Michel, and Kropotkin.[38] Later Le Compte and Kropotkin gave talks to the Homerton Social Democratic Club and to the Stratford Radical and Dialectical Club.[39]

Kropotkin returned to Thonon in late 1882. Soon he was arrested by the French government, tried at Lyon, and sentenced by a police-court magistrate (under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune) to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the IWA (1883). The French Chamber repeatedly agitated on his behalf, and he was released in 1886. He was invited to Britain by Henry Seymour and Charlotte Wilson and all three worked on Seymour's The Anarchist. Soon after Wilson and Kropotkin would split from the individualist anarchist Seymour and found the Freedom Press, an anarchist newspaper which continues to this day. Kropotkin was a regular contributor while Wilson was integral to the administrative and financial running of the paper until she resigned its editorship in 1895. He settled near London, living at various times in Harrow, then Bromley, where his daughter and only child, Alexandra, was born on April 15, 1887.[40] [41] He also lived for a number of years in Brighton.[42] While living in London, Kropotkin became friends with a number of prominent English-speaking socialists, including William Morris and George Bernard Shaw.[43]

In 1916 Kropotkin and Jean Grave drafted a document -Manifesto of the Sixteen- which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Central Powers during the First World War. Because of the Manifesto, Kropotkin found him self isolated by the mainstream[44] of the anarchist movement.[45]

Return to Russia[edit]

In 1917, after the February Revolution, Kropotkin returned to Russia after 40 years of exile. His arrival was greeted by cheering crowds of tens of thousands of people. He was offered the ministry of education in the Provisional Government, which he promptly refused, feeling that working with them would be a violation of his anarchist principles.[46]

His enthusiasm for the changes occurring in the Russian Empire expanded when Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution. He had this to say about the October Revolution: "During all the activities of the present revolutionary political parties we must never forget that the October movement of the proletariat, which ended in a revolution, has proved to everybody that a social revolution is within the bounds of possibility. And this struggle, which takes place worldwide, has to be supported by all means - all the rest is secondary. The party of the Bolsheviks was right to adopt the old, purely proletarian name of "Communist Party". Even if it does not achieve everything that it would like to, it will nevertheless enlighten the path of the civilised countries for at least a century. Its ideas will slowly be adopted by the peoples in the same way as in the nineteenth century the world adopted the ideas of the Great French Revolution. That is the colossal achievement of the October Revolution." .... "I see the October Revolution as an attempt to bring the preceding February Revolution to its logical conclusion with a transition to communism and federalism." [47]

Even though he led a life on the margins of the revolutionary upheaval, Kropotkin became increasingly critical of the methods of the Bolshevik dictatorship, and went on to express these feelings in writing. “Unhappily, this effort has been made in Russia under a strongly centralized party dictatorship. This effort was made in the same way as the extremely centralized and Jacobin endeavor of Babeuf. I owe it to you to say frankly that, according to my view, this effort to build a communist republic on the basis of a strongly centralized state communism under the iron law of party dictatorship is bound to end in failure. We are learning to know in Russia how not to introduce communism, even with a people tired of the old regime and opposing no active resistance to the experiments of the new rulers.”[48]

Death[edit]

Kropotkin died of pneumonia on February 8, 1921, in the city of Dmitrov, and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. Thousands of people marched in his funeral procession, including, with Vladimir Lenin's approval,[49] anarchists carrying banners with anti-Bolshevik slogans.[50] The occasion, the last public demonstration of anarchists in Soviet Russia, saw engaged speeches by Emma Goldman and Aron Baron. In some versions of Peter Kropotkin[51]'s Conquest of Bread, the mini-biography states that this would be the last time that Kropotkin's supporters would be allowed to freely rally in public.

In 1957 the Dvorets Sovetov station of the Moscow Metro was renamed Kropotkinskaya in his honor.[52]

Philosophy[edit]

Critique of capitalism[edit]

Kropotkin pointed out what he considered to be the fallacies of the economic systems of feudalism and capitalism. He believed they create poverty and artificial scarcity while promoting privilege. Instead, he proposed a more decentralized economic system based on mutual aid, mutual support, and voluntary cooperation, asserting that the tendencies for this kind of organization already exist, both in evolution and in human society.[53]

He disagreed with the Marxian critique of capitalism, including the labour theory of value, believing there was no necessary link between work performed and the prices of commodities. His attacks on the institution of wage-labour were based more on the power employers exerted over employees – which he claimed was made possible by the state protecting private ownership of productive resources – than the extraction of surplus value from their labour.[54]

Cooperation and competition[edit]

In 1902, Kropotkin published his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which provided an alternative view of animal and human survival, beyond the claims of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy proffered at the time by some "social Darwinists" such as Francis Galton. He argued that "it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human".[55] Kropotkin explored the widespread use of cooperation as a survival mechanism in human societies - through their many stages - and among animals. He used many real-life examples in an attempt to show that the main factor in facilitating evolution is cooperation between individuals in free-associated societies and groups, without central control, authority, or compulsion. He did so in order to counteract the concept of fierce competition as the core of evolution, which concept provided a rationalization for the dominant political, economic, and social theories[which?] of the time and for the prevalent interpretations of Darwinism.[citation needed] In the last chapter, he wrote:[56]

In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species[...] in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits[...] and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development[...] are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.

— Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Conclusion.

Kropotkin did not deny the presence of competitive urges in humans, but did not see them as the driving force of history (as did capitalists and social Darwinists).[57]:262 He believed that seeking out conflict proved to be socially beneficial only in attempts to destroy unjust, authoritarian institutions such as the State or the Church, which he saw as stifling human creativity and freedom and impeding human instinctual drive towards sociality and cooperation.[58]

Kropotkin's observations of cooperative tendencies in indigenous peoples (pre-feudal, feudal, and those remaining in modern societies) led him to conclude that not all human societies were based on competition, such as those of industrialized Europe, and that many societies exhibited cooperation among individuals and groups as the norm. He also concluded that most pre-industrial and pre-authoritarian societies (where he claimed that leadership, central government and class did not exist) actively defend against the accumulation of private property by, for example, equally distributing within the community a person's possessions when he died, or by not allowing a gift to be sold, bartered or used to create wealth (see Gift economy).[59]

Mutual aid[edit]

In his 1892 book The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He believed that should a society be socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services required by it, then no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange will prevent everyone to take what they need from the social product. He supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens of exchange for goods and services.[60]

Kropotkin believed that Bakunin's collectivist economic model was simply a wage system by a different name,[61] and that such a system would breed the same type of centralization and inequality as a capitalist wage system. He stated that it is impossible to determine the value of an individual's contributions to the products of social labor, and thought that anyone who was placed in a position of trying to make such determinations would wield authority over those whose wages they determined.[62]

According to Kirkpatrick Sale:[55]

With Mutual Aid especially, and later with Fields, Factories, and Workshops, Kropotkin was able to move away from the absurdist limitations of individual anarchism and no-laws anarchism that had flourished during this period and provide instead a vision of communal anarchism, following the models of independent cooperative communities he discovered while developing his theory of mutual aid. It was an anarchism that opposed centralized government and state-level laws as traditional anarchism did, but understood that at a certain small scale, communities and communes and co-ops could flourish and provide humans with a rich material life and wide areas of liberty without centralized control.

Self-sufficiency[edit]

Kropotkin's focus on local production led to his view that a country should strive for self-sufficiency – manufacture its own goods and grow its own food, lessening dependence on imports. To these ends he advocated irrigation and greenhouses to boost local food production ability.[63]

Works[edit]

Books[edit]

- In Russian and French Prisons, London: Ward and Downey; 1887. Anarchist Archives e-text

- The Conquest of Bread (Paris, 1892) Project Gutenberg e-text, Project LibriVox audiobook

- The Great French Revolution, 1789–1793 (French original: Paris, 1893; English translation: London, 1909). e-text (in French), Anarchist Library e-text (in English)

- The Terror in Russia, 1909, RevoltLib e-text

- Words of a Rebel, 1885, RevoltLib e-text

- Fields, Factories and Workshops (London and New York, 1898).

- Memoirs of a Revolutionist, London : Smith, Elder; 1899. Anarchist Library e-text, Anarchy Archives e-text

- Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (London, 1902) Project Gutenberg e-text, Project LibriVox audiobook

- Russian Literature: Ideals and Realities (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1905). Anarchy Archives e-text

- The State: Its Historic Role, published 1946, RevoltLib e-text

- Ethics: Origin and Development (unfinished). Included as first part of Origen y evolución de la moral (Spanish e-text)

- Modern Science and Anarchism, 1930, RevoltLib e-text

Pamphlets[edit]

- Communism and Anarchy (1901)

- Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles (1887)

- An Appeal To The Young (1880)

- The Industrial Village of the Future (1884)

- Law and Authority (1886)

- The Coming Anarchy (1887)

- The Place of Anarchy in Socialist Evolution (1886)

- The Wage System (1920)

- The Commune of Paris (1880)

- Anarchist Morality (1898)

- Expropriation

- The Great French Revolution and Its Lesson (1909)

- Process Under Socialism (1887)

- Are Prisons Necessary? Chapter X from "In Russian and French Prisons" (1887)

- The Coming War (1913)

- Wars and Capitalism (1914)

- Revolutionary Government (1892)

- The Scientific Basis of Anarchy (1887)

- The Fortress Prison of St. Petersburg (1883)

- Advice to Those About to Emigrate (1893)

- Some of the Resources of Canada (1898)

- Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

- Revolutionary Studies (1892)

- Direct Action of Environment and Evolution (1920)

- The Present Crisis in Russia (1901)

- The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

- The State: Its Historic Role (1897)

- On Economics Selected Passages from his Writings (1898–1913)

- On the Teaching of Physiography (1893)

- War! (1914)

Articles[edit]

- "The Constitutional Agitation in Russia," 1905.

- "Brain Work and Manual Work," 1890.

- "Manifesto of the Sixteen," 1916.

- "Organized Vengeance Called 'Justice.'"

- "A Proposed Communist Settlement: A New Colony for Tyneside or Wearside."

- "What Geography Ought to Be," 1885.

- "Organized Vengeance Called 'Justice'"

- "On Order"

- "Maxím Górky," 1904

- "Research on the Ice age", Notices of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, 1876.

- "Baron Toll", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 23, No. 6. (Jun. 1904), pp. 770–772, JSTOR

- "The population of Russia", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2. (Aug. 1897), pp. 196–202, JSTOR

- "The old beds of the Amu-Daria", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3. (Sep. 1898), pp. 306–310, JSTOR

- "Russian Schools and the Holy Synod," 1902

- Mr. Mackinder; Mr. Ravenstein; Dr. Herbertson; Prince Kropotkin; Mr. Andrews; Cobden Sanderson; Elisée Reclus, "On Spherical Maps and Reliefs: Discussion", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 22, No. 3. (Sep. 1903), pp. 294–299, JSTOR

- "The desiccation of Eur-Asia", Geographical Journal, 23 (1904), 722–41.

- “Finland” in Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), 1911 (in part; with Joseph R. Fisher and John Scott Keltie)

- "Finland: A Rising Nationality," Nineteenth Century, 1885

- “Anarchism” in Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), 1911

- "Anti-militarism. Was it properly understood?", Freedom, vol.XXVIII, no. 307 (November 1914), pp. 82–83.

- "An open letter of Peter Kropotkin to the Western workingmen", The Railway Review (29 June 1917), p. 4.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Slatter, John. "Kropotkin, Pyotr Alexeyevich." Encyclopedia of Russian History. 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Peter Marshall (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. PM Press. p. 177. ISBN 9781604862706.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy, MobileReference (2007). Works of Leo Tolstoy. MobileReference. ISBN 9781605011561.

- ^ Richard T. Gray, ed. (2005). A Franz Kafka Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170. ISBN 9780313303753.

- ^ Winfried Scharlau (2011). Who is Alexander Grothendieck? Part 1: Anarchy. Books on Demand. p. 30. ISBN 9783842340923.

In June 1918 Makhno visited his idol Peter Kropotkin in Moscow...

- ^ Mina Graur (1997). An Anarchist Rabbi: The Life and Teachings of Rudolf Rocker. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 22–36. ISBN 978-0-312-17273-2.

- ^ Louis G. Perez, ed. (2013). "Kōtoku Shūsui (1871–1911)". Japan at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 190. ISBN 9781598847420.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. The Ecology of Freedom. Oakland: AK Press, 2005. p.11

- ^ "Noam Chomsky Reading List". Left Reference Guide. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Kropotkin". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Stoddart, D. R. (1975). "Kropotkin, Reclus, and 'Relevant' Geography". Area. 7 (3): 188–190.

- ^ http://www.users.skynet.be/AL/LIBRAIRIE/increva/vol3/1418.htm

- ^ "Anarchist Encyclopedia: Manifeste des Seize / Manifesto of the Sixteen (16)". web.archive.org. 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin entry on 'anarchism' from the Encyclopædia Britannica (eleventh ed.), Internet Archive. Public Domain text.

- ^ a b Harman, Oren (2011). The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 20. ISBN 9780393339994.

- ^ Woodcock, George & Avakumović, Ivan (1990). Peter Kropotkin: From Prince to Rebel. Black Rose Books. p. 13. ISBN 9780921689607.

- ^ Roger N. Baldwin, "The Story of Kropotkin's Life," in Kropotkin's Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings, ed. by Baldwin (Orig. 1927; Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1970), p. 13.

- ^ Martin A. Miller, "Introduction" to P. A. Kropotkin, Selected Writings on Anarchism and Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970; p. 7.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 63.

- ^ Winkle, Justin, ed. (2009). "Kropotkin, Petr Alexseyevich". The Concise New Makers of Modern Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 425. ISBN 9780415477826.

- ^ Todes, Daniel Philip (1989). Darwin Without Malthus: The Struggle for Existence in Russian Evolutionary Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780195058307.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. p. 270.

- ^ a b Miller, "Introduction," pg. 8.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. p. 198.

- ^ a b c Miller, "Introduction," p. 9.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. p. 214.

- ^ Ward, Dana (2010). "Alchemy in Clarens: Kropotkin and Reclus, 1877–1881". In Jun, Nathan J. & Wahl, Shane. New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 211. ISBN 9780739132418.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ a b Marshall, Peter (2010). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. PM Press. p. 311. ISBN 9781604860641.

- ^ Riggenbach, Jeff (March 4, 2011). "The Anarchism of Peter Kropotkin". Mises Daily. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. pp. 235–236.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. pp. 282–287.

- ^ Cahm, Caroline (2002). Kropotkin: And the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism, 1872–1886. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780521891578.

- ^ Todes, Daniel Philip (1989). Darwin Without Malthus: The Struggle for Existence in Russian Evolutionary Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780195058307.

- ^ Bell, Jeffrey A. (2002). "Kropotkin, Pyotr". In Bell, Jeffrey A. Industrialization and Imperialism, 1800–1914: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 199. ISBN 9780313314513.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. pp. 417–423.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (2010). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. reproduction of 1899 edition. Dover Publications. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-486-47316-1.

- ^ a b Bantman, Constance (2006). "Internationalism without an International? Cross-Channel Anarchist Networks, 1880–1914". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 84 (84–4): 965. doi:10.3406/rbph.2006.5056. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ Young, Sarah J. (January 9, 2011). "Russians in London: Pyotr Kropotkin". Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ Shpayer, Haia (June 1981). "British Anarchism 1881–1914: Reality and Appearance" (PDF). p. 20. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ "Alexandra Kropotkin" Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America by Paul Avrich (2005) AK Press pps. 16-18; Retrieved May 8, 2017

- ^ Bromley Council guide to blue plaques

- ^ Peter Marshall Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism, London: Fontana, 1993, p.315

- ^ Gibbs, A. (2001). A Bernard Shaw Chronology. Springer. p. 365. ISBN 9780230599581.

- ^ peter marshall, p 332, Demanding the impossible 1993

- ^ THE PALGRAVE HANDBOOK OF ANARCHISM, Edited by Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams, page 404 publication Palgrave Macmillan, 2019

- ^ Burbank, Jane (1989). Intelligentsia and Revolution: Russian Views of Bolshevism, 1917–1922. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780195045734.

- ^ https://www.bolshevik.info/meeting-lenin-kropotkin-bonc-brujevic1919.htm

- ^ "Letter to the Workers of Western Europe", in Kropotkin’s Revolutionary Pamphlets. Dover Publications Inc. 1970. p. 254. ISBN 9780486225197.

- ^ Goldman, Emma (1931). Living My Life. Dover Publications. pp. 867–868. ISBN 0-486-22543-7.

- ^ Album Die Beerdigung von P.A. Kropotkin in Moskau, 13. Februar 1921 = Funeral of P.A. Kropotkin in Moscow, February 13, 1921; publisher: Ausländisches Büro zur Schaffung der Russischen Anarcho-Syndikalistischen Konföderation; 1922

- ^ "The Biography of Prince Pyotr Kropotkin".

- ^ Muscovites Step Up Effort To Rename Metro Station Honoring Tsar's Killer.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1902). Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. p. 223.

- ^ Bekken, John (2009). Radical Economics and Labour. Chapter 2: Peter Kropotkin's anarchist economics for a new society. London & New York: Routledge. p. 223. ISBN 0-415-77723-2.

- ^ a b Sale, Kirkpatrick (July 1, 2010) Are Anarchists Revolting?, The American Conservative

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1902). quotation from Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

- ^ Gallaher, Carolyn; Dahlman, Carl T.; Gilmartin, Mary; Mountz, Alison; Shirlow, Peter (2009). Key Concepts in Political Geography. London: SAGE. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-4129-4672-8. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ Vucinich, Alexander (1988). Darwin in Russian Thought. University of California Press. p. 349. ISBN 9780520062832.

- ^ Morris, David. Anarchism Is Not What You Think It Is – And There's a Whole Lot We Can Learn from It, AlterNet, February 13, 2012

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1892). The Conquest of Bread. p. 201.

- ^ Kropotkin wrote: "After the Collectivist Revolution instead of saying 'twopence' worth of soap, we shall say 'five minutes' worth of soap." (quoted in Brauer, Fae (2009). "Wild Beasts and Tame Primates: 'Le Douanier' Rosseau's Dream of Darwin's Evolution". In Larsen, Barbara Jean. The Art of Evolution: Darwin, Darwinisms, and Visual Culture. UPNE. p. 211. ISBN 9781584657750.)

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. AK Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781904859482.

- ^ Adams, Matthew S. (2015-06-04). Kropotkin, Read, and the Intellectual History of British Anarchism: Between Reason and Romanticism. Springer. ISBN 9781137392626.

Further reading[edit]

Books on Kropotkin[edit]

- Mac Laughlin, Jim (2016). Kropotkin and the Anarchist Intellectual Tradition. Pluto Press (UK). ISBN 9780745335131.

- Alan, Barnard (March 2004). "Mutual Aid and the Foraging Mode of Thought: Re-reading Kropotkin on the Khoisan". Social Evolution & History. 3 (1): 3–21.

- Joll, James (1980). The Anarchists. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03641-7. LCCN 80-010503.

- Woodcock, George & Avakumovic, Ivan (1950). The Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin.

- Miller, Martin A. (1976). Kropotkin. University of Chicago Press.

- Morris, Brian (2004). Kropotkin: the Politics of Community. Humanity Press.

- The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Police by Alex Butterworth (Pantheon Books, 2010)

- Engelbert, Arthur (2012). Help! Gegenseitig behindern oder helfen. Eine politische Skizze zur Wahrnehmung heute. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-5017-6.

- Cahm, Caroline (1989). Kropotkin and the rise of revolutionary anarchism 1872–1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 36445 0.

- Walter, Nicolas (2004). "Kropotkin, Peter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42326. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Journal articles[edit]

- Gould, S.J. (June 1997). "Kropotkin was no crackpot". Natural History. 106: 12–21.

- Basic Kropotkin: Kropotkin and the History of Anarchism by Brian Morris, Anarchist Communist Editions pamphlet no.17 (The Anarchist Federation, October 2008).

- Efremenko D., Evseeva Y. Studies of Social Solidarity in Russia: Tradition and Modern Trends. // American Sociologist, v. 43, 2012, no. 4, pp. 349–365. – NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Prince P. A. Kropotkin: [Obituary] // Nature. 1921. Vol. 106. P. 735-736.

External links[edit]

- Works by Peter Kropotkin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Peter Kropotkin at Internet Archive

- Works by Peter Kropotkin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Kropotkin Page at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

- The Peter Kropotkin text archive on libcom.org library

- BlackCrayon.com: People: Peter Kropotkin

- Peter Kropotkin entry at the Anarchy Archives with complete collected works

- Peter Kropotkin-Short Documentary on YouTube

- Summary of records in The National Archives and elsewhere, with a link to the National Register of Archives pages.

- Kropotkin's works at TheAnarchistLibrary.org

- Kropotkin's grave at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Site Elisée Reclus

- Kropotkin: The Coming Revolution short documentary in Kropotkin's own words.

- Map of the Southern Half of Eastern Siberia and Parts of Mongolia, Manchuria, and Sakhalin: For a General Sketch of the Orography of Eastern Siberia by Kropotkin, from the World Digital Library

- Pyotr Alexeevich Kropotkin at Find a Grave

- Album of the funeral of P.A. Kropotkin in Moscow (1922)

- The virtual Museum of P.A.Kropotkin

- Newspaper clippings about Peter Kropotkin in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

- Peter Kropotkin

- 1842 births

- 1921 deaths

- 19th-century atheists

- 20th-century atheists

- Anarchist theorists

- Anarcho-communists

- Anti-consumerists

- Atheist writers

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Imperial Russian emigrants to France

- Imperial Russian emigrants to Switzerland

- Imperial Russian emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Libertarian socialists

- Historians of the French Revolution

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- Narodniks

- People from Moscow Governorate

- Rurikids

- Russian anarchists

- Russian anti-capitalists

- Russian anti-fascists

- Russian atheists

- Russian communists

- Russian explorers

- Russian geographers

- Russian memoirists

- Russian newspaper editors

- Russian non-fiction writers

- Russian philosophers

- Russian political writers

- Russian revolutionaries

- Russian science writers

- Russian scientists

- Russian socialists

- Russian writers

- Russian zoologists

- Writers from Moscow

- Human geographers