Thiruvalluvar

Thiruvalluvar | |

|---|---|

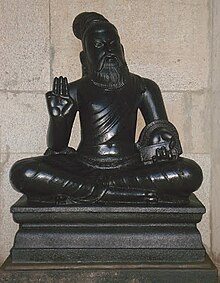

A statue of Valluvar | |

| Born | Uncertain; 31 BCE[a] |

| Other names | Valluvar, Mudharpaavalar, Deivappulavar, Gnanavettiyaan, Maadhaanupangi, Naanmuganaar, Naayanaar, Poyyirpulavar, Dhevar, Perunaavalar[1] |

Notable work | Tirukkural |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Tamil nadu |

Main interests | Ethics, ahimsa, justice, virtue, politics, education, family, friendship, love |

Notable ideas | Common ethics and morality |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Thiruvalluvar, commonly known as Valluvar, was a celebrated Tamil poet and philosopher. He is best known for authoring the Thirukkuṛaḷ, a collection of couplets on ethics, political and economical matters, and love. The text is considered the greatest work of the Tamil literature and one of the finest works on ethics and morality.

Much of the information about Valluvar comes from legendary accounts, and little is known with certainty about his family background, religious affiliation, or birthplace. He is believed to have lived in Madurai and later in the town of Mylapore (a neighbourhood of the present-day Chennai), and his floruit is dated variously from 4th century BCE to 5th century CE, based on the traditional accounts and the linguistic analyses of his writings.

Valluvar has literally influenced every scholar down the ages since his time across the ethical, social, political, economical, religious, philosophical, and spiritual spheres.[2][3] Because the life, culture and ethics of the Tamils are considered to be solely defined in terms of the values set by the Kural literature, the government and the people of Tamil land alike venerate Valluvar and his work with utmost reverence.[4] He is known by numerous honorific designations, such as Saint, First Poet, Divine Poet, Brahma, and Great Scholar.[5]

Contents

Life[edit]

There is negligible authentic information about the life of Valluvar.[6] In fact, neither his actual name nor the original title of his work can be determined with certainty.[7] Tirukkural itself does not name its author. Reminiscing this, Monsieur Ariel, a French scholar of the 19th century, famously said of the Tirukkural thus: Ce livre sans nom, par un auteur sans nom ("The book without a name by an author without a name").[8] The name Thiruvalluvar was first mentioned in the later text Tiruvalluva Maalai (c. 10th century).[9]

Various claims have been made regarding Valluvar's occupation. One tradition claims that he was a Paraiyar weaver.[10] Another theory is that he must have been from the agricultural caste of Vellalars because he extols agriculture in his work.[11] Mu Raghava Iyengar speculated that "valluva" in his name is a variation of "vallabha", the designation of a royal officer.[11] S. Vaiyapuri Pillai derived his name from "valluvan" (a Paraiyar caste of royal drummers) and theorized that he was "the chief of the proclaiming boys analogous to a trumpet-major of an army".[11][12]

The poem Kapilar Agaval, purportedly written by Kapilar, describes its author as a brother of Valluvar. It states that they were children of a Pulaya woman named Adi and a Brahmin named Bhagwan.[13] The poem claims that the couple had seven children, including three sons (Thiruvalluvar, Kapilar, and Atikaman) and four sisters (Awai, Uppai, Uruvai, and Velli).[14] However, this legendary account is false.[15][16] Kamil Zvelebil dates Kapilar Agaval to 15th century CE, based on its language.[13] Various biographies mention the name of Valluvar's wife as Vasuki,[17] but such details are of doubtful historicity.[18]

George Uglow Pope called Valluvar "the greatest poet of South India", but according to Kamil Zvelebil, he does not seem to have been a poet. According to Zvelebil, while the author handles the metre very skillfully, the Tirukkuṛaḷ does not feature "true and great poetry" throughout the work, except, notably, in the third book which deals with love and pleasure. This suggests that Valluvar's main aim was not to produce a work of art, but rather an instructive text focused on wisdom, justice, and ethics.[19]

Date[edit]

The Tirukkuṛaḷ has been dated variously from 300 BCE to 5th century CE. According to traditional accounts, it was the last work of the third Sangam and was subjected to a divine test (which it passed). The scholars who believe this tradition, such as Somasundara Bharathiar and M. Rajamanickam, date the text to as early as 300 BCE. Historian K. K. Pillay assigned it to the early 1st century CE.[20]

Linguist Kamil Zvelebil is certain that Tirukkuṛaḷ does not belong to the Sangam period and dates it to somewhere between 450 and 500 CE.[20] His estimate is based on the language of the text, its allusions to the earlier works, and its borrowing from some Sanskrit treatises.[11] Zvelebil notes that the text features several grammatical innovations, that are absent in the older Sangam literature. The text also features a higher number of Sanskrit loan words compared with these older texts.[21] According to Zvelebil, besides being part of the ancient Tamil literary tradition, the author was also a part of the "one great Indian ethical, didactic tradition", as a few of his verses seem to be translations of the verses in Sanskrit texts such as Mānavadharmaśāstra and Kautilya's Arthaśāstra.[22]

S. Vaiyapuri Pillai assigned the work to c. 650 CE, believing that it borrowed from some Sanskrit works of the 6th century CE.[20] Zvelebil disagrees with this assessment, pointing out that some of the words that Pillai believed to be Sanskrit loan words have now been proved to be of Dravidian origin by Thomas Burrow and Murray Barnson Emeneau.[22]

With the exact date of Valluvar still under debate, taking the latest of the estimated dates, the Tamil Nadu government officially ratified 31 BCE as the year of Valluvar. From 18 January 1935, as suggested by Maraimalai Adigal, the Valluvar Year was added to the calendar.[23] Thus, the Valluvar year is calculated by adding 31 to any year of the common era.[24]

Birthplace[edit]

The exact place of Valluvar's birth remains uncertain. Valluvar is believed to have lived in Madurai and later in the town of Mayilapuram or Thirumayilai (present-day Mylapore in Chennai).[12] The poem Kapilar Akaval states that Valluvar was born on the top of an oil-nut tree in Mayilapuram.[14], while verse 21 of the Tiruvalluva Maalai claims that he was born in Madurai.[7]

In 2005, a 3-member research team from the Kanyakumari Historical and Cultural Research Centre (KHCRC) claimed that Valluvar was born in Thirunayanarkurichi, a village in present-day Kanyakumari district. Their claim was based on an old Kani tribal leader who told them that Valluvar was a king who ruled the "Valluvanadu" territory in the hilly tracts of the Kanyakumari district.[25]

Death[edit]

Valluvar was affected profoundly by Vasuki’s death that he secluded himself from social life and devoted the rest of his life to religious contemplation. At his deathbed, he expressed a strange desire according to which his body should not be cremated but exposed in the open air outside the town to be devoured by crows and other scavenging animals, and it was done so.[26]

Religion[edit]

Valluvar is generally thought to have belonged to either Jainism or Hinduism.[27][28][29] Valluvar's treatment of the concept of ahimsa or non-violence, which is the principal concept of both these religions, bolsters this. In particular, his treatment of the chapters on strict vegetarianism (or veganism) (Chapters 26 and 32) and non-killing (Chapter 33) reflects the Jain precepts, where these are stringently enforced.[28] The three parts that the Kural literature is divided into, namely, aram (virtue), porul (wealth) and inbam (love), aiming at attaining veedu (ultimate salvation), follow, respectively, the four foundations of Hinduism, namely, dharma, artha, kama and moksha.[30] His mentioning of God Vishnu in couplets 610 and 1103 and Goddess Lakshmi in couplets 167, 408, 519, 565, 568, 616, and 617 hints at the Vaishnavite beliefs of Valluvar. Other eastern beliefs of the poet found in the book include previous birth and rebirth, seven births, and some ancient Indian astrological concepts, among others.[31] Nevertheless, even in the introductory chapter, Valluvar’s invocation of the Supreme Being does not give us a clue to his religion.[32]

However, owing to the Kural text's non-denominational nature, almost every religious group in India, including Christianity, has claimed the work and its author as one of their own.[11]

Jainism[edit]

Kamil Zvelebil believes that the ethics of the Tirukkuṛaḷ reflect the Jain moral code (e.g. Tirukkuṛaḷ 251-260 talks about moral vegetarianism, and Tirukkuṛaḷ 321-333 talks against killing). Zvelebil states that the text features "several purely Jaina technical terms", such as the following epithets of God:[33]

- Malarmicaiyekinan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 3), "he who walked upon the [lotus] flower"

- Aravaliyantanan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 3), "the Brahmin [who had] the wheel of dharma"

- Enkunattan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 9), "one of the eight-fold qualities"

- Atipakavan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 1), "the Primeval Lord"

Zvelebil notes that even the 13th century Hindu scholar Parimēlaḻakar, who wrote a commentary on Tirukkuṛaḷ, accepted that such epithets are applicable only to the Jain Arhat. Some other epithets mentioned in the text also reflect a "strong ascetic flavour" characteristic of Jainism:[33]

- Ventutal ventamai ilan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 4), "he who has neither desire nor aversion"

- Porivayil aintavittan (Tirukkuṛaḷ 6), "he who has destroyed the gates of the five senses"

Zvelebil further states that Valluvar seems to have been "cognizant of the latest developments" in Jainism.[33] Zvelebil theorizes that he was probably "a learned Jain with eclectic leanings", who was well-acquainted with the earlier Tamil literature, and also had some knowledge of the Sanskrit texts.[6]

Hinduism[edit]

Multiple Hindu sects have claimed Valluvar as one of their own and have tried to align his verses with their own teachings.[34] Shaivites have characterised Valluvar as a devotee of Shiva and have installed his images in their temples.[35]

Buddhism[edit]

Anti-caste activist Iyothee Thass, who converted to Buddhism, claimed that Valluvar was originally called "Tiruvalla Nayanar", and was a Buddhist.[36] Thass described him as follows: Tiruvalla Nayanar was born in Madurai, as the son of King Kanchan and Queen Upakesi. When he grew up, the prince wandered across many countries, until he joined a Buddhist sangam at Thinnanur. There, he learned about the Buddhist doctrine from his guru Chakaya Munivar.[37] Thass further contended that the name "Tirukkuṛaḷ" is a reference to the Buddhist Tripiṭaka.[37] He claims that Valluvar's book was originally called Tirikural ("Three Kurals"), because it adhered to the three Buddhist scriptures Dhamma Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka, and Vinaya Pitaka.[36] According to Thass, the legend that presents Valluvar as the son of a Brahmin father and a Paraiyar mother was invented by Brahmins, who wanted to Hinduise a Buddhist text.[36]

Christianity[edit]

Christian missionary George Uglow Pope claimed that the Tirukkuṛaḷ shows Christian influence, particularly from the Alexandrian school. He theorized that Valluvar came into contact with Christian teachers such as Pantaenus in Mayilapur and incorporated the ideas from the Christian scriptures in his text. Pope praises the Kural as an "echo of the 'Sermon on the Mount.'" In the Introduction to his English translation of the Kural, Pope even claims, "I cannot feel any hesitation in saying that the Christian Scriptures were among the sources from which the poet derived his inspiration." Zvelebil states that Pope was "rather overenthusiastic in discovering strong traces of Christianity" in Tirukkuṛaḷ and dismisses Pope's hypothesis as based on "vague impressions".[38] Since the 1960s, some South Indian Christians led by M. Deivanayagam at the Madras Christian College, have even characterized Valluvar as a disciple of Thomas the Apostle.[39] According to this theory, Thomas visited present-day Chennai, where Valluvar listened to his lectures on the Sermon of the Mount.[18] Several Tamil scholars, both Christian and Hindu, have criticized this claim as inaccurate.[39] Nevertheless, the chapters on the ethics of moral vegetarianism (Chapters 26 and 32) and non-killing (Chapter 33), which the Kural emphasizes emphatically and unambiguously unlike the Bible or other Abrahamic religious texts, suggest that the ethics of the Kural is rather a reflection of the Jaina moral code than of Christian ethics.[28]

Literary works[edit]

Tirukkuṛaḷ is the chief work attributed to Valluvar. It is one of the most revered ancient works in the Tamil language. It contains 1330 couplets, which are divided into 133 sections of 10 couplets each. The first 38 sections are about ethics (aram), the next 70 about political and economic matters (porul), and the rest are about love (inbam).[6] The text has been translated into several languages,[40] including a translation into Latin by Constanzo Beschi in 1699, which helped make the work known to European intellectuals.

Claims are made that Valluvar was also the author of two Tamil texts on medicine, Gnana Vettiyan (1500 verses) and Pancharathnam (500 verses), although many scholars claim that they were by a later author with the same name,[41] since they appear to have been written in the 16th and 17th centuries. These books, 'Pancharathnam' and 'Gnana Vettiyan', contribute to Tamil science, literature and other ayurvedic medicines.[42] In addition to these, there are 15 other texts that are attributed to Valluvar, namely, Rathna Sigamani (800 verses), Karpam (300 verses), Nadhaantha Thiravukol (100 verses), Naadhaantha Saaram (100 verses), Vaithiya Suthram (100 verses), Karpaguru Nool (50 verses), Muppu Saathiram (30 verses), Vaadha Saathiram (16 verses), Muppu Guru (11 verses), Kavuna Mani (100 verses), Aeni Yettram (100 verses), Guru Nool (51 verses), Sirppa Chinthamani (a text on astrology), Tiruvalluvar Gyanam, and Tiruvalluvar Kanda Tirunadanam.[43] However, several scholars such as Devaneya Pavanar deny this claim.[44]

Memorials[edit]

A temple-like memorial to Valluvar, Valluvar Kottam, was built in Chennai in 1976.[45] This monument complex consists of structures usually found in Dravidian temples,[46] including a temple car[47] carved from three blocks of granite, and a shallow, rectangular pond.[45] The auditorium adjoining the memorial is one of the largest in Asia and can seat up to 4,000 people.[48]

There is a 133-foot tall statue of Valluvar erected at Kanyakumari at the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, where the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the Indian Ocean converge. The 133 feet denote Tirukkuṛaḷ's 133 chapters or athikarams and the show of three fingers denote the three themes Aram, Porul, and Inbam, that is, the sections on morals, wealth and love. The statue was designed by V. Ganapati Sthapati, a temple architect from Tamil Nadu.[49] On 9 August 2009, a statue was unveiled in Ulsoor, near Bengaluru, also making it the first of its kind in India for a poet of a local language to be installed in its near states other than his own home land. There is also a statue of Valluvar outside the School of Oriental and African Studies in Russell Square, London.[50]

The Government of Tamil Nadu celebrates the 15th (16th on leap years) of January (the 2nd of the month of 'Thai' as per Tamil Calendar) as Thiruvalluvar Day in the poet's honour, as part of the Pongal celebrations.[51]

See also[edit]

- Sarvajna and Tiruvalluvar statue installation

- Valluvar Kottam, a monument dedicated to Thiruvalluvar

- List of Sangam poets

- Thiruvalluvar year

Notes[edit]

a. ^ The period of Valluvar is dated variously by scholars from c. 4th century BCE to c. 5th century CE, based on various methods of analysis, including traditional accounts and linguistics analyses. The officially accepted date, however, is 31 BCE, as ratified by the government in 1921, and the Valluvar Year is being followed ever since.[24] For more in-depth analysis, see Dating the Tirukkural.

Citations[edit]

- ^ P. R. Natarajan 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Velusamy and Faraday, 2017, pp. 7–13.

- ^ Sundaramurthi, 2000, p. 624.

- ^ Zvelebil, 1973, pp. 156-171.

- ^ a b c Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 155.

- ^ a b Kamil Zvelebil 1975, p. 125.

- ^ Pope, 1886, p. i.

- ^ Cutler Blackburn 2000, pp. 449-482.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil 1975, pp. 124-125.

- ^ a b c d e Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 156.

- ^ a b Pavanar, 2017, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b Kamil Zvelebil 1975, p. 227.

- ^ a b Kamil Zvelebil 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Shuddhananda A. Sarma 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi 1997, p. 202.

- ^ Pavanar, 2017, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Mohan Lal 1992, p. 4341.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Kamil Zvelebil 1975, p. 124.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 169.

- ^ a b Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 171.

- ^ Thiruvalluvar Ninaivu Malar, 1935, p. 117.

- ^ a b Arumugam, 2014, pp. 5, 15.

- ^ Research team claims to have found Thiruvalluvar's kingdom, 2005.

- ^ Robinson, 2001, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 156-171.

- ^ Mohan Lal 1992, pp. 4333–4334.

- ^ P. S. Sundaram 1990, pp. 7–16.

- ^ P. R. Natarajan 2008, pp. 1–6.

- ^ a b c Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 157.

- ^ Swamiji Iraianban 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Raj Pruthi & Bela Rani Sharma 1995, p. 113.

- ^ a b c K. A. Geetha 2015, p. 49.

- ^ a b K. A. Geetha 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 156-157.

- ^ a b Jan A. B. Jongeneel 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Translation of the Tamil literary work thirukkuRaL in world languages, 2012.

- ^ Cuppiramaṇiyan̲, 1980.

- ^ Zimmermann, 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Vedanayagam, 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Pavanar, 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b Abram(Firm), 2003, p. 421.

- ^ Tourist Guide to Tamil Nadu , 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Hancock, 2010, p. 113–.

- ^ Kamath, 2010, p. 34–.

- ^ TiruvaḷḷuvarSubramuniyaswami, 2000, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Anonymous, n.d.

- ^ Various, 2010, p. 13.

References[edit]

- A. Arumugam (2014). வள்ளுவம் [Valluvam]. Philosophy Textbooks Series. Chennai: Periyar E.V.Ramasamy-Nagammai Education and Research Trust.

- Cutler Blackburn (2000). "Corruption and Redemption: The Legend of Valluvar and Tamil Literary History". Modern Asian Studies. 34: 449–482. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003632. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi, ed. (1997). Studies in South Indian History and Culture. V.R. Ramachandra Dikshitar Centenary Committee. OCLC 37579357.

- Jan A. B. Jongeneel (2009). Jesus Christ in World History: His Presence and Representation in Cyclical and Linear Settings. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-59688-3.

- K. A. Geetha (2015). Contesting Categories, Remapping Boundaries: Literary Interventions by Tamil Dalits. Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-4438-7304-8.

- A. A. Manavalan (2009). Essays and Tributes on Tirukkural (1886–1986 AD) (1 ed.). Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- Edward Jewitt Robinson (2001). Tamil Wisdom. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL. p. 155. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1975). Tamil Literature. Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1991). Tamil Traditions on Subrahmaṇya-Murugan. Institute of Asian Studies.

- Mohan Lal (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- P. R. Natarajan (2008). Thirukkural: Aratthuppaal (in Tamil) (First ed.). Chennai: Uma Padhippagam.

- G. Devaneya Pavanar (2017). திருக்குறள் [Tirukkural: Tamil Traditional Commentary] (in Tamil) (4 ed.). Chennai: Sri Indhu Publications.

- Raj Pruthi; Bela Rani Sharma (1995). Buddhism Jainism And Women. Anmol. ISBN 978-81-7488-085-7.

- Shuddhananda A. Sarma (2007). Tamil Siddhas: a study from historical, socio-cultural, and religio-philosophical perspectives. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Swamiji Iraianban (1997). Ambrosia of Thirukkural. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-346-5.

- N. Velusamy and Moses Michael Faraday (Eds.) (2017). Why Should Thirukkural Be Declared the National Book of India? (in Tamil and English) (First ed.). Chennai: Unique Media Integrators. ISBN 978-93-85471-70-4.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- I. Sundaramurthi (Ed.) (2000). குறளமுதம் [Kuralamudham] (in Tamil) (1st ed.). Chennai: Tamil Valarcchi Iyakkagam.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- Pope, G. U. (1886). The Sacred Kurral of Tiruvalluva Nayanar. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. (Introduction).

- Vedanayagam, Rama (2017). திருவள்ளுவ மாலை மூலமும் எளிய உரை விளக்கமும் [Tiruvalluva Maalai: Moolamum Eliya Urai Vilakkamum] (in Tamil) (1 ed.). Chennai: Manimekalai Prasuram.

- Marion Zimmermann (September 2007). A Short Introduction: The Tamil Siddhas and the Siddha Medicine of Tamil Nadu. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-77126-9. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- David Abram; Rough Guides (Firm) (2003). South India. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-103-6. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Ca. Vē Cuppiramaṇiyan̲ (1980). Papers on Tamil studies. International Institute of Tamil Studies. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Mary Elizabeth Hancock (8 October 2008). The politics of heritage from Madras to Chennai. Indiana University Press. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-253-35223-1. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Rina Kamath (2000). Chennai. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-1378-5. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Tiruvaḷḷuvar; Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (1 January 2000). Tirukural. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-390-8. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Various. Tourist Guide to South India. Sura Books. ISBN 978-81-7478-175-8. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Thiruvalluvar Ninaivu Malar". 1935.

- "Research team claims to have found Thiruvalluvar's kingdom". Zee News. 26 April 2005.

- "Translation of the Tamil literary work thirukkuRaL in world languages". K. Kalyanasundaram. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Tourist Guide to Tamil Nadu. Sura Books. ISBN 978-81-7478-177-2. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Anonymous (n.d.). Tiruvalluvar. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thiruvalluvar. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thiruvalluvar |

- Works by or about Thiruvalluvar at Internet Archive

- Works by Thiruvalluvar at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Tirukkural

- Tamil poets

- Indian male philosophers

- Ancient Indian philosophers

- Ancient Indian poets

- Indian male poets

- Poets from Tamil Nadu

- Nonviolence advocates

- Scholars from Tamil Nadu

- Simple living advocates

- Moral philosophers

- Classical humanists

- Philosophers from Tamil Nadu

- Deified people

- Philosophers of love

- Political philosophers

- Social philosophers

- Philosophers of ethics and morality

- Vegetarianism

- Sangam poets