Wyrd

This article may need to be rewritten entirely to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2018) |

| Look up wyrd in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Wyrd is a concept in Anglo-Saxon culture roughly corresponding to fate or personal destiny. The word is ancestral to Modern English weird, which retains its original meaning only dialectically.

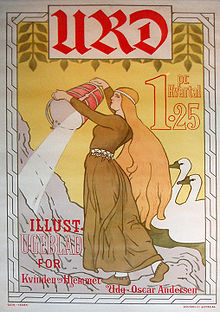

The cognate term in Old Norse is urðr, with a similar meaning, but also personalized as one of the Norns, Urðr (anglicized as Urd) and appearing in the name of the holy well Urðarbrunnr in Norse mythology.

Contents

Etymology[edit]

The Old English term wyrd derives from a Common Germanic term *wurđíz.[1] Wyrd has cognates in Old Saxon wurd,[2] Old LIndsay Kutten German wurt,[3] Old Norse urðr, Dutch worden (to become), and German werden. The Proto-Indo-European root is *wert- "to turn, rotate", in Common Germanic *wirþ- with a meaning "to come to pass, to become, to be due" (also in weorþ, the notion of "origin" or "worth" both in the sense of "connotation, price, value" and "affiliation, identity, esteem, honour and dignity.)[citation needed]

Old English wyrd is a verbal noun formed from the verb weorþan, meaning "to come to pass, to become".[4] The term developed into the modern English adjective weird.[5] Adjectival use develops in the 15th century, in the sense "having the power to control fate", originally in the name of the Weird Sisters, i.e. the classical Fates, in the Elizabethan period detached from their classical background as fays, and most notably appearing as the Three Witches in Shakespeare's Macbeth.[6] In many editions of the play, the editors include a footnote associating the "Weird Sisters" with Old English wyrd or "fate".[7] From the 14th century, to weird was also used as a verb in Scots, in the sense of "to preordain by decree of fate".[citation needed] Of note is the use of "weird" in Frank Herbert's Dune to connote an ability to amplify or empower, e.g., certain words being used as "weirding words."

The modern spelling weird first appears in Scottish and Northern English dialects in the 16th century and is taken up in standard literary English from the 17th century. The regular modern English form would have been wird, from Early Modern English werd. The replacement of werd by weird in the northern dialects is "difficult to account for".[8]

The most common modern meaning of weird - "odd, strange" - is first attested in 1815, originally with a connotation of the supernatural or portentous (especially in the collocation weird and wonderful), but by the early 20th century increasingly applied to everyday situations.[9]

Fate in Germanic mythology[edit]

_by_Johannes_Gehrts.jpg/220px-Die_Nornen_(1889)_by_Johannes_Gehrts.jpg)

Wyrd is a feminine noun,[10] and its Norse cognate urðr, besides meaning "fate", is the name of one of the Norns; urðr is literally "that which has come to pass", verðandi is "what is in the process of happening" (the present participle of the verb cognate to weorþan) and skuld "debt, guilt" (from a Germanic root *skul- "to owe", also found in English shall). "Wyrd has been interpreted as a pre-Christian Germanic concept or goddess of fate by some scholars. Other scholars deny a pagan signification of wyrd in Old English literature, but assume that wyrd was a pagan deity in the pre-Christian period."[11]

Between themselves, the Norns weave fate or ørlǫg (from ór "out, from, beyond" and lǫg "law", and may be interpreted literally as "beyond law"). According to Voluspa 20, the three Norns "set up the laws", "decided on the lives of the children of time" and "promulgate their ørlǫg". Frigg, on the other hand, while she "knows all ørlǫg", "says it not herself" (Lokasenna 30). ørlǫglausa "ørlǫg-less" occurs in Voluspa 17 in reference to driftwood, that is given breath, warmth and spirit by three gods, to create the first humans, Ask ("Ash") and Embla (possibly "Elm").

Mentions of wyrd in Old English literature include The Wanderer, "Wyrd bið ful aræd" ("Fate remains wholly inexorable") and Beowulf, "Gæð a wyrd swa hio scel!" ("Fate goes ever as she shall!"). In The Wanderer, wyrd is irrepressible and relentless. She or it "snatches the earls away from the joys of life," and "the wearied mind of man cannot withstand her" for her decrees "change all the world beneath the heavens".[12]

Modern usage in Paganism and Satanism[edit]

Like other aspects of Germanic paganism, the concept of wyrd plays a role in modern Germanic Heathenry.

The Satanic, Neo-Nazi-affiliated, human-sacrifice-promoting organization Order of Nine Angles makes frequent reference to wyrd in its publicly available writings, which Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke's 2002 book Black Sun speculates may indicate roots in a pre-Christian native tradition of paganism or Wicca.[13]

Other uses[edit]

The Wyrd Mons, a mountain on Venus, is named after an "Anglo-Saxon weaving goddess".[14] According to J. Duncan Spaeth, "Wyrd (Norse Urd, one of the three Norns) is the Old English goddess of Fate, whom even Christianity could not entirely displace."[15]

See also[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wyrd |

References[edit]

- ^ Karsten, Gustaf E. Michelle Kindler Philology, University of Illinois Press, 1908, p. 12.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Weird". Online Etymology Dictionary. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Weird". Online Etymology Dictionary. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Weird". Online Etymology Dictionary. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Weird". Online Etymology Dictionary. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Karsten, Gustaf E. Germanic Philology, University of Illinois Press, 1908, p. 12.

- ^ de Grazia, Margreta and Stallybrass, Peter. The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text, George Washington University, 1993, p. 263.

- ^ OED. c.f. phonological history of Scots.

- ^ OED; c.f. Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. Harper Collins ISBN 0-06-270084-7 (1995:876).

- ^ "WYRD, Gender: Feminine", Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- ^ Frakes, Jerold C. The Ancient Concept of casus and its Early Medieval Interpretations, Brill, 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Ferrell, C. C. Old Germanic Life in the Anglo-Saxon, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1894, pp. 402-403.

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. Black Sun: Aryan cults, esoteric Nazism, and the politics of identity, NYU Press, 2002, pp. 215-216.

- ^ "Wyrd Mons". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature.

- ^ Spaeth, J. Duncan (1921). Old English Poetry. Princeton University Press. p. 208.

- Bertha S. Philpotts, 'Wyrd and Providence in Anglo-Saxon Thought', Essays and Studies 13 (1928), 7-27.

- Ian McNish, 'Wyrd, Causality and Providence. A Speculative Essay', Mankind Quarterly 44 (2004).[1]