Kirchhoff's circuit laws

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Kirchhoff's laws are two equalities that deal with the current and potential difference (commonly known as voltage) in the lumped element model of electrical circuits. They were first described in 1845 by German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff.[1] This generalized the work of Georg Ohm and preceded the work of James Clerk Maxwell. Widely used in electrical engineering, they are also called Kirchhoff's rules or simply Kirchhoff's laws. These laws can be applied in time and frequency domains and form the basis for network analysis.

Both of Kirchhoff's laws can be understood as corollaries of Maxwell's equations in the low-frequency limit. They are accurate for DC circuits, and for AC circuits at frequencies where the wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation are very large compared to the circuits.

Contents

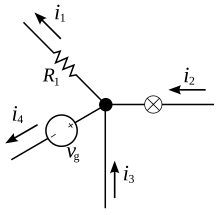

Kirchhoff's current law (KCL)[edit]

This law is also called Kirchhoff's first law, Kirchhoff's point rule, or Kirchhoff's junction rule (or nodal rule).

This law states that, for any node (junction) in an electrical circuit, the sum of currents flowing into that node is equal to the sum of currents flowing out of that node; or equivalently:

The algebraic sum of currents in a network of conductors meeting at a point is zero.

Recalling that current is a signed (positive or negative) quantity reflecting direction towards or away from a node, this principle can be succinctly stated as:

where n is the total number of branches with currents flowing towards or away from the node.

The law is based on the conservation of charge where the charge (measured in coulombs) is the product of the current (in amperes) and the time (in seconds). If the net charge in a region is constant, the KCL will hold on the boundaries of the region.[2][3] This means that KCL relies on the fact that the net charge in the wires and components is constant.

Uses[edit]

A matrix version of Kirchhoff's current law is the basis of most circuit simulation software, such as SPICE. Kirchhoff's current law is used with Ohm's law to perform nodal analysis.

KCL is applicable to any lumped network irrespective of the nature of the network; whether unilateral or bilateral, active or passive, linear or non-linear.

Kirchhoff's voltage law (KVL)[edit]

This law is also called Kirchhoff's second law, Kirchhoff's loop (or mesh) rule, and Kirchhoff's second rule.

This law states that

The directed sum of the potential differences (voltages) around any closed loop is zero.

Similarly to KCL, it can be stated as:

Here, n is the total number of voltages measured.

| Derivation of Kirchhoff's voltage law |

|---|

| A similar derivation can be found in The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume II, Chapter 22: AC Circuits.[3]

Consider some arbitrary circuit. Approximate the circuit with lumped elements, so that (time-varying) magnetic fields are contained to each component and the field in the region exterior to the circuit is negligible. Based on this assumption, the Maxwell-Faraday equation reveals that

in the exterior region. If each of the components have a finite volume, then the exterior region is simply connected, and thus the electric field is conservative in that region. Therefore, for any loop in the circuit, we find that

where are paths around the exterior of each of the components, from one terminal to another. |

Generalization[edit]

In the low-frequency limit, the voltage drop around any loop is zero. This includes imaginary loops arranged arbitrarily in space – not limited to the loops delineated by the circuit elements and conductors. In the low-frequency limit, this is a corollary of Faraday's law of induction (which is one of Maxwell's equations).

This has practical application in situations involving "static electricity".

Limitations[edit]

KCL and KVL both depend on the lumped element model being applicable to the circuit in question. When the model is not applicable, the laws do not apply. KCL and KVL result from the assumptions of the lumped element model.

KCL is dependent on the assumption that the net charge in any wire, junction or lumped component is constant. Whenever the electric field between parts of the circuit is non-negligible, such as when two wires are capacitively coupled, this may not be the case. This occurs in high-frequency AC circuits, where the lumped element model is no longer applicable.[4] For example, in a transmission line, the charge density in the conductor will constantly be oscillating.

On the other hand, KVL relies on the fact that the action of time-varying magnetic fields are confined to individual components, such as inductors. In reality, the induced electric field produced by an inductor is not confined, but the leaked fields are often negligible.

Modelling real circuits with lumped elements

The lumped element approximation for a circuit is accurate at low enough frequencies. At higher frequencies, leaked fluxes and varying charge densities in conductors become significant. To an extent, it is possible to still model such circuits using parasitic components. If frequencies are too high, it may be more appropriate to simulate the fields directly using finite element modelling or other techniques.

To model circuits so that KVL and KCL can still be used, it's important to understand the distinction between physical circuit elements and the ideal lumped elements. For example, a wire is not an ideal conductor. Unlike an ideal conductor, wires can inductively and capacitively couple to each other (and to themselves), and have a finite propagation delay. Real conductors can be modeled in terms of lumped elements by considering parasitic capacitances distributed between the conductors to model capacitive coupling, or parasitic (mutual) inductances to model inductive coupling.[4] Wires also have some self-inductance, which is the reason that decoupling capacitors are necessary.

Example[edit]

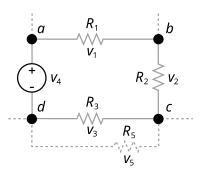

Assume an electric network consisting of two voltage sources and three resistors.

According to the first law we have

The second law applied to the closed circuit s1 gives

The second law applied to the closed circuit s2 gives

Thus we get a system of linear equations in :

Which is equivalent to

Assuming

the solution is

has a negative sign, which means that the direction of is opposite to the assumed direction i.e. is directed upwards.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Oldham, Kalil T. Swain (2008). The doctrine of description: Gustav Kirchhoff, classical physics, and the "purpose of all science" in 19th-century Germany (Ph. D.). University of California, Berkeley. p. 52. Docket 3331743.

- ^ Athavale, Prashant. "Kirchoff's current law and Kirchoff's voltage law" (PDF). Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b "The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. II Ch. 22: AC Circuits". www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- ^ a b Ralph Morrison, Grounding and Shielding Techniques in Instrumentation Wiley-Interscience (1986) ISBN 0471838055

- Paul, Clayton R. (2001). Fundamentals of Electric Circuit Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-37195-5.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0810-8.

- Graham, Howard Johnson, Martin (2002). High-speed signal propagation : advanced black magic (10. printing. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 0-13-084408-X.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kirchhoff's circuit laws. |

- Divider Circuits and Kirchhoff's Laws chapter from Lessons In Electric Circuits Vol 1 DC free ebook and Lessons In Electric Circuits series.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}i_{1}={\frac {1}{1100}}{\text{A}}\\[6pt]i_{2}={\frac {4}{275}}{\text{A}}\\[6pt]i_{3}=-{\frac {3}{220}}{\text{A}}\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cfd39f5713de745cd55eb5f6bcb6d3cc7ba6783c)