Book

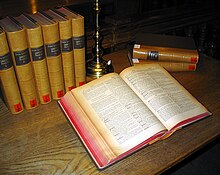

A book is a set of printed sheets of paper held together between two covers. The sheets of paper are usually covered with a text, language and illustrations that is the main point of a printed book.

A writer of a book is called an author. Someone who draws pictures in a book is called an illustrator. Books can have more than one author or illustrator.

A book can also be a text in a larger collection of texts. That way a book is perhaps written by one author, or it only treats one subject area. Books in this sense can often be understood without knowing the whole collection. Examples are the Bible, the Illiad or the Odyssey – all of them consist of a number of books in this sense of the word. Encyclopedias often have separate articles written by different people, and published as separate volumes. Each volume is a book.

Hardcover books have hard covers made of cardboard covered in cloth or leather and are usually sewn together. Paperback books have covers of stiff paper and are usually glued together. The words in books can be read aloud and recorded on tapes or compact discs. These are called "audiobooks".

Books can be borrowed from a library or bought from a bookstore. People can make their own books and fill them with family photos, drawings, or their own writing. Some books are empty inside, like a diary, address book, or photo album. Most of the time, the word "book" means that the pages inside have words printed or written on them.

Some books are written just for children, or for entertainment, while other books are for studying something in school such as math or history. Many books have photographs or drawings.

Contents

Types of books[change | change source]

There are two main kinds of book text: fiction and non-fiction.

Fiction[change | change source]

These books are novels, about stories that did not happen, and have been imagined by the author. Some books are based on real events from history, but the author has created imaginary characters or dialogue for the events.

Non-fiction[change | change source]

Books of non-fiction are about true facts or things that have really happened. Some examples are dictionaries, cookbooks, textbooks for learning in school, or a biography (someone's life story).

Historical[change | change source]

Between the written manuscript and the book lie several inventions. Manuscripts are hand-made, but books are now industrial products.

Manuscripts[change | change source]

A common type of manuscript was the scroll, which was a long sheet rolled up. The sheet could have been made of papyrus (made by the Egyptians, by weaving the inner stems of the papyrus plant and then hammering them together), or parchment or vellum (very thin animal skin, first used by the ancient Greeks), or paper (made from plant fibers, invented by the Chinese). Manuscripts of this kind lasted to the 16th century and beyond. Turning the manuscript into a book required several developments.

The codex[change | change source]

The Romans were the first people to put separate pieces of manuscript between covers, to form a codex. This was more convenient to handle and store than scrolls, but was not yet a book as we understand it.

Printing[change | change source]

Scrolls and codices were written and copied by hand. The Chinese invented woodblock printing, where shapes are carved out of a block of wood, then ink is applied to the carved side, and the block is pressed onto paper. This woodcut method was slow because the symbols and pictures were made by cutting away the surrounding wood.

Johannes Gutenberg was the first to invent a machine for printing, the printing press, in the 15th century. This involved more than just a press, it involved the production of movable metal type suitable for the machine process.

Initially, the machines were slow, and needed a printer to work with them. Fast and automatic machines did not arrive until the 19th century.[1][2][3]

Paper and ink[change | change source]

Paper had been invented in China in the 8th century, but it was kept secret for a long time. In Europe hand-made paper was available from about 1450. It was expensive, and the early printing was a slow process. Therefore books remained rare. In 1800 the first machines for making paper from wood pulp were invented. New kinds of inks were also invented for various purposes, and machines were driven by steam engines and later by electricity.[4]

The common cheap supply of paper fed the faster printing machines, and books became cheaper. At the same time, in America, Britain and continental Europe, more people learnt to read. So, in the 19th century, many ordinary people could afford to buy books and could actually read them. Also in the 19th century came public libraries, so poorer people could get access to the best books.[5]

Binding[change | change source]

Printing was done on large sheets of paper, which were then folded, guillotined (cut) and sewn in sections, and finally placed into the covers. All these processes were done by machines during the 19th century.

Today[change | change source]

Today some of the technologies have been changed, especially those involving illustration and typography. However, books look much the same as they did, with more illustration in colour, but basically the same. That is because experience has shown that readers need certain things for pleasurable reading. Graphic design and typography are the practical arts used to make books attractive and useful to readers.

Related pages[change | change source]

References[change | change source]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book. |

| The Simple English Wiktionary has a definition for: book. |

- ↑ Lefebre L & Martin H-J. 1990. The coming of the book. new ed, London.

- ↑ Chappell W. & Bringhurst R. A short history of the printed word. Hartley & Marks, Vancouver.

- ↑ Moran, James 1971. The development of the printing press. Royal Society of Arts.

- ↑ Twyman, Michael 1970. Printing 1770–1970: an illustrated history of its development and uses in England. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- ↑ Altick R.D. 1957. The English common reader: a social history of the mass reading public 1800–1900. University of Chicago Press.