National Review

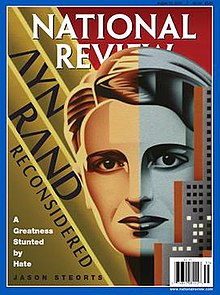

National Review cover for August 30, 2010 | |

| Editor | Rich Lowry |

|---|---|

| Categories | Editorial magazine, conservatism |

| Frequency | Biweekly |

| Publisher | E. Garrett Bewkes IV[1] |

| Total circulation (2017) | 90,904[2] |

| First issue | November 19, 1955 |

| Company | National Review, Inc. |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0028-0038 |

National Review (NR) is an American semi-monthly editorial magazine focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955.[3] It is currently edited by Rich Lowry.

Since its founding, the magazine has played a significant role in the development of conservatism in the United States, helping to define its boundaries[3] and promoting fusionism while establishing itself as a leading voice on the American right.[3][4][5]

The online version, National Review Online, is edited by Charles C. W. Cooke and includes free content and articles separate from the print edition.[6]

Contents

History[edit]

Background[edit]

Before National Review's founding in 1955, the American right was a largely unorganized collection of people who shared intertwining philosophies but had little opportunity for a united public voice. They also wanted to marginalize what they saw as the antiwar, noninterventionistic views of the Old Right.[7]

In 1953 moderate Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, and many major magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post, Time, and Reader's Digest were strongly conservative and anticommunist, as were many newspapers including the Chicago Tribune and St. Louis Globe-Democrat. A few small-circulation conservative magazines, such as Human Events and The Freeman, preceded National Review in developing Cold War Conservatism in the 1950s.[8]

Early years[edit]

In 1953, Russell Kirk published The Conservative Mind, which sought to trace an intellectual bloodline from Edmund Burke[9] to the Old Right in the early 1950s. This challenged the popular notion that no coherent conservative tradition existed in the United States.[9]

A young William F. Buckley Jr. was greatly influenced by Kirk's concepts. Buckley, from a wealthy oil family, first tried to purchase Human Events, but was turned down. He then met Willi Schlamm, the experienced editor of The Freeman; they would spend the next two years raising the $300,000 necessary to start their own weekly magazine, originally to be called National Weekly.[10] (A magazine holding the trademark to the name prompted the change to National Review.) The statement of intentions read:[11]

Middle-of-the-Road, qua Middle of the Road, is politically, intellectually, and morally repugnant. We shall recommend policies for the simple reason that we consider them right (rather than “non-controversial”); and we consider them right because they are based on principles we deem right (rather than on popularity polls)... The New Deal revolution, for instance, could hardly have happened save for the cumulative impact of The Nation and The New Republic, and a few other publications, on several American college generations during the twenties and thirties.

Contributors[edit]

On November 19, 1955, Buckley’s magazine began to take shape. Buckley assembled an eclectic group of writers: traditionalists, Catholic intellectuals, libertarians and ex-Communists. The group included: Russell Kirk, James Burnham, Frank Meyer, and Willmoore Kendall, Catholics L. Brent Bozell and Garry Wills. The former Time editor Whittaker Chambers, who had been a Communist spy in the 1930s, eventually became a senior editor. In the magazine’s founding statement Buckley wrote:[12]

Let’s Face it: Unlike Vienna, it seems altogether possible that did National Review not exist, no one would have invented it. The launching of a conservative weekly journal of opinion in a country widely assumed to be a bastion of conservatism at first glance looks like a work of supererogation, rather like publishing a royalist weekly within the walls of Buckingham Palace. It is not that of course; if National Review is superfluous, it is so for very different reasons: It stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no other is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.

As editors and contributors, Buckley especially sought out intellectuals who were ex-Communists or had once worked on the far Left, including Whittaker Chambers, William Schlamm, John Dos Passos, Frank Meyer and James Burnham.[13] When James Burnham became one of the original senior editors, he urged the adoption of a more pragmatic editorial position that would extend the influence of the magazine toward the political center. Smant (1991) finds that Burnham overcame sometimes heated opposition from other members of the editorial board (including Meyer, Schlamm, William Rickenbacker, and the magazine's publisher William A. Rusher), and had a significant effect on both the editorial policy of the magazine and on the thinking of Buckley himself.[14]

Mission to conservatives[edit]

National Review aimed to make conservative ideas respectable,[3] in an age when the dominant view of conservative thought was expressed by Lionel Trilling in 1950:[15]

In the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation... the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not... express themselves in ideas but only... in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.

William Buckley Jr., on the purpose of National Review:

[National Review] stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it… it is out of place because, in its maturity, literate America rejected conservatism in favor of radical social experimentation…since ideas rule the world, the ideologues, having won over the intellectual class, simply walked in and started to…run just about everything. There never was an age of conformity quite like this one, or a camaraderie quite like the Liberals’.[16]

National Review promoted Barry Goldwater heavily during the early 1960s. Buckley and others involved with the magazine took a major role in the "Draft Goldwater" movement in 1960 and the 1964 presidential campaign. National Review spread his vision of conservatism throughout the country.[17]

The early National Review faced occasional defections from both left and right. Garry Wills broke with N.R. and became a liberal commentator. Buckley’s brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell Jr., who ghostwrote The Conscience of a Conservative for Barry Goldwater, left and started the short-lived traditionalist Catholic magazine, Triumph in 1966.

Defining the boundaries of conservatism[edit]

Buckley and Meyer promoted the idea of enlarging the boundaries of conservatism through fusionism, whereby different schools of conservatives, including libertarians, would work together to combat what were seen as their common opponents.[3]

Buckley and his editors used his magazine to define the boundaries of conservatism—and to exclude people or ideas or groups they considered unworthy of the conservative title. Therefore, they attacked the John Birch Society, George Wallace, and anti-Semites.[3][18]

Buckley's goal was to increase the respectability of the conservative movement; as Rich Lowry noted: "Mr. Buckley's first great achievement was to purge the American right of its kooks. He marginalized the anti-Semites, the John Birchers, the nativists and their sort."[19]

In 1957, National Review editorialized in favor of white leadership in the South, arguing that "the central question that emerges... is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes – the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race."[20][21] By the 1970s National Review advocated colorblind policies and the end of affirmative action.[22]

In the late 1960s, the magazine denounced segregationist George Wallace, who ran in Democratic primaries in 1964 and 1972 and made an independent run for president in 1968. During the 1950s, Buckley had worked to remove anti-Semitism from the conservative movement and barred holders of those views from working for National Review.[23] In 1962 Buckley denounced Robert W. Welch Jr. and the John Birch Society as "far removed from common sense" and urged the Republican Party to purge itself of Welch's influence.[24]

After Goldwater[edit]

After Goldwater was defeated by Lyndon Johnson in 1964, Buckley and National Review continued to champion the idea of a conservative movement, which was increasingly embodied in Ronald Reagan. Reagan, a longtime subscriber to National Review, first became politically prominent during Goldwater's campaign. National Review supported his challenge to President Gerald Ford in 1976 and his successful 1980 campaign.

During the 1980s N.R. called for tax cuts, supply-side economics, the Strategic Defense Initiative, and support for President Reagan's foreign policy against the Soviet Union. The magazine criticized the Welfare state and would support the Welfare reform proposals of the 1990s. The magazine also regularly criticized President Bill Clinton. It first embraced, then rejected, Pat Buchanan in his political campaigns. A lengthy 1996 National Review editorial called for a "movement toward" drug legalization.[25]

In 1985, the National Review and Buckley were represented by attorney J. Daniel Mahoney during the magazine's $16 million libel suit against The Spotlight.[26]

Political views and content[edit]

Victor Davis Hanson, a regular contributor since 2001, sees a broad spectrum of conservative and anti-liberal contributors:

- In other words, a wide conservative spectrum—paleo-conservatives, neo-conservatives, tea-party enthusiasts, the deeply religious and the agnostic, both libertarians and social conservatives, free-marketeers and the more protectionist—characterizes National Review. The common requisite is that they present their views as a critique of prevailing liberal orthodoxy but do so analytically and with decency and respect.[27]

The magazine has been described as "the bible of American conservatism".[28]

Donald Trump[edit]

In 2015, the magazine published an editorial entitled "Against Trump," calling him a "philosophically unmoored political opportunist" and announcing its opposition to his candidacy for the Republican nomination for president.[29] The magazine declined to endorse any of the candidates in the United States presidential election of 2016. Since Trump's election to the presidency, the National Review editorial board has continued to criticize him.[30][31][32]

However, contributors to National Review and National Review Online take a variety of positions on Trump. Liberal commentator Peter Beinart criticized Lowry and Hanson for "breez[ing] by Trump’s blatant assaults on long-held conservative values in their rush to find something, anything, to congratulate him for,"[33] while National Review contributors such as Ramesh Ponnuru and Jonah Goldberg have remained critical of Trump.[34] In a Washington Post feature on conservative magazines, T.A. Frank noted: "From the perspective of a reader, these tensions make National Review as lively as it has been in a long time."[35]

National Review Online[edit]

A popular feature of National Review is the web version of the magazine, National Review Online ("N.R.O."), which includes a digital version of the magazine, with articles updated daily by National Review writers, and conservative blogs. The on-line version is called N.R.O. to distinguish it from the paper magazine. It also features free articles, though these deviate in content from its print magazine. The site's editor is Charles C. W. Cooke.[36]

Each day, the site posts new content consisting of conservative, libertarian, and neoconservative opinion articles, including some syndicated columns, and news features.

It also features two blogs:

- The Corner[37] – postings from a select group of the site's editors and affiliated writers discussing the issues of the day

- Bench Memos[38] – legal and judicial news and commentary

Markos Moulitsas, who runs the liberal Daily Kos web-site, told reporters in August 2007 that he does not read conservative blogs, with the exception of those on N.R.O.: "I do like the blogs at the National Review—I do think their writers are the best in the [conservative] blogosphere," he said.[39]

National Review Institute[edit]

The N.R.I. works in policy development and helping establish new advocates in the conservative movement. National Review Institute was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1991 to engage in policy development, public education, and advocacy that would advance the conservative principles he championed.[40]

Finances[edit]

As with most political opinion magazines in the United States, National Review carries little corporate advertising. The magazine stays afloat by donations from subscribers and black-tie fund raisers around the country. The magazine also sponsors cruises featuring National Review editors and contributors as lecturers.[28][41]

Buckley said in 2005 that the magazine had lost about $25,000,000 over fifty years.[42]

Presidential primary endorsements[edit]

National Review sometimes endorses a candidate during the primary election season. Editors at National Review have said, "Our guiding principle has always been to select the most conservative viable candidate."[43] This statement echoes what has come to be called "The Buckley Rule". In a 1967 interview, in which he was asked about the choice of presidential candidate, Buckley said, "The wisest choice would be the one who would win... I'd be for the most right, viable candidate who could win."[44]

The following candidates were officially endorsed by National Review:

|

Editors and contributors[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The magazine's current editor-in-chief is Rich Lowry. Many of the magazine's commentators are affiliated with think-tanks such as The Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute. Prominent guest authors have included Newt Gingrich, Mitt Romney, Peter Thiel, and Ted Cruz in the on-line and paper edition.

Notable current contributors[edit]

Current and past contributors to National Review (N.R.) magazine, National Review Online (N.R.O.), or both:

- Elliott Abrams

- Richard Brookhiser, senior editor

- Mona Charen

- Charles C. W. Cooke, editor of N.R.O..

- Frederick H. Fleitz

- David A. French

- John Fund, N.R.O. national-affairs columnist

- Jim Geraghty

- Jonah Goldberg, N.R. senior editor

- Victor Davis Hanson

- Paul Johnson

- Roger Kimball

- Larry Kudlow

- Stanley Kurtz

- Yuval Levin

- James Lileks

- Rob Long, N.R. contributing editor

- Kathryn Jean Lopez

- Rich Lowry, N.R. editor

- Andrew C. McCarthy

- John J. Miller N.R. national political reporter

- Stephen Moore, financial columnist

- Deroy Murdock

- Jay Nordlinger

- Michael Novak

- John O'Sullivan, N.R. editor-at-large

- Ramesh Ponnuru

- David Pryce-Jones

- Tom Rogan

- Reihan Salam

- Ben Shapiro

- Katherine Timpf

- George F. Will

- Kevin D. Williamson, "roving correspondent" at N.R.

Notable past contributors[edit]

- Renata Adler

- Steve Allen

- Wick Allison

- W. H. Auden

- Edward C. Banfield

- Jacques Barzun

- Peter L. Berger

- Allan Bloom

- George Borjas

- Robert Bork

- L. Brent Bozell Jr.

- Peter Brimelow

- Pat Buchanan

- Jed Babbin

- Myrna Blyth

- Christopher Buckley

- William F. Buckley Jr., founder

- James Burnham

- John R. Chamberlain

- Whittaker Chambers

- Shannen W. Coffin

- Robert Conquest

- Richard Corliss

- Robert Costa

- Ann Coulter

- Arlene Croce

- Guy Davenport

- John Derbyshire

- Joan Didion

- John Dos Passos

- Rod Dreher

- Dinesh D'Souza

- John Gregory Dunne

- Max Eastman

- Eric Ehrmann

- Thomas Fleming

- Samuel T. Francis

- Milton Friedman

- David Frum

- Francis Fukuyama

- Eugene Genovese

- Paul Gigot

- Nathan Glazer

- Stuart Goldman

- Paul Gottfried

- Mark M. Goldblatt

- Michael Graham

- Ethan Gutmann

- Ernest van den Haag

- Jeffrey Hart

- Henry Hazlitt

- Will Herberg

- Christopher Hitchens

- Harry V. Jaffa

- Arthur Jensen

- John Keegan

- Willmoore Kendall

- Hugh Kenner

- Florence King

- Phil Kerpen

- Russell Kirk

- Charles Krauthammer

- Irving Kristol

- Dave Kopel

- Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn

- Michael Ledeen

- Fritz Leiber

- John Leonard

- Mark Levin

- John Lukacs

- Arnold Lunn

- Richard Lynn

- Alasdair MacIntyre

- Harvey C. Mansfield

- Malachi Martin

- Frank Meyer

- Scott McConnell

- Forrest McDonald

- Ludwig von Mises

- Alice-Leone Moats

- Raymond Moley

- Thomas Molnar

- Charles Murray

- Richard Neuhaus

- Robert Nisbet

- Robert Novak

- Michael Oakeshott

- Kate O'Beirne

- Conor Cruise O'Brien

- Revilo P. Oliver

- Thomas Pangle

- Isabel Paterson

- Ezra Pound

- Paul Craig Roberts

- Murray Rothbard

- William A. Rusher, publisher, 1957–88

- J. Philippe Rushton

- Steve Sailer

- Pat Sajak

- Catherine Seipp

- Daniel Seligman

- John Simon

- Joseph Sobran

- Thomas Sowell

- Whit Stillman

- Theodore Sturgeon

- Mark Steyn

- Thomas Szasz

- Allen Tate

- Jared Taylor

- Terry Teachout

- Taki Theodoracopulos

- Ralph de Toledano

- Auberon Waugh

- Evelyn Waugh

- Richard M. Weaver

- Robert Weissberg

- Frederick Wilhelmsen

- Garry Wills

- James Q. Wilson

- Tom Wolfe

- Byron York

- R. V. Young

Washington editors[edit]

- L. Brent Bozell Jr.

- Neal B. Freeman

- George Will, 1973–76[48]

- Neal B. Freeman, 1978–81

- John McLaughlin, 1981–89

- William McGurn, 1989–1992

- Kate O'Beirne

- Robert Costa, 2012–13

- Eliana Johnson, 2014–16

Controversies[edit]

Obama conspiracy theories[edit]

In June 2008, six days after Hillary Clinton conceded to Obama in the Democratic primary, National Review correspondent Jim Geraghty published an article encouraging the Obama campaign to release the candidate's birth certificate in order "to squash all the conspiracy theories once and for all." Geraghty's column notes that it was unlikely that Obama was born in Kenya. Attorney Loren Collins, who has tracked the origins of birtherism for years, says that Geraghty may have "unwittingly shined a national spotlight on a fringe internet theory."[49] Geraghty's article "became fodder for cable television."[50] In a 2009 editorial, the National Review editorial board called conspiracies about Obama's citizenship "untrue," writing: "Like Bruce Springsteen, he has a lot of bad political ideas; but he was born in the U.S.A."[51]

One National Review article said that Obama's parents could be communists because “for a white woman to marry a black man in 1958, or ’60, there was almost inevitably a connection to explicit Communist politics”.[52][53]

By 2018, Dinesh D'Souza was on the National Review masthead, despite stirring controversy for a number of years making inflammatory remarks and promoting conspiracy theories. D'Souza had shared a meme calling former President Barack Obama a “gay Muslim” and suggesting Michelle Obama was a man. In comments that earned rebukes from National Review colleagues, D'Souza said that Hungarian-born George Soros was a "collection boy for Hitler and the Nazis," attacked Roy Moore accuser Beverly Young Nelson, said that accusations against Roy Moore were “most likely fabricated,” and described Rosa Parks as an "overrated Democrat".[54][55][56]

Climate change[edit]

According to Philip Bump of The Washington Post, National Review "has regularly criticized and rejected the scientific consensus on climate change".[57] In 2015, the magazine published an intentionally deceptive graph that suggested that there was no climate change.[57][58][59] The graph set the lower and upper bounds of the chart at -10 and 110 degree Fahrenheit and zoomed out so as to obscure warming trends.[59]

In 2017, National Review published an article alleging that a top NOAA scientist claimed that National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) engaged in data manipulation and rushed a study based on faulty data in order to influence the Paris climate negotiations.[60] The article largely repeated allegations made in The Daily Mail without independent verification.[61] The scientist in question later rebuked the claims made by the National Review, noting that he did not accuse NOAA of data manipulation but instead raised concerns about "the way data was handled, documented and stored, raising issues of transparency and availability".[60]

In 2014, climate scientist Michael E. Mann sued the National Review after columnist Mark Steyn accused Mann of fraud and referenced a quote from Competitive Enterprise Institute writer Rand Simberg that called Mann "the Jerry Sandusky of climate science, except that instead of molesting children, he has molested and tortured data."[62][63][64] Civil-liberties organizations such as the ACLU and the Electronic Frontier Foundation and several publications such as The Washington Post expressed support for National Review in the lawsuit, filing amicus briefs in their defense.[65] There is no evidence that Mann has engaged in fraud.[64]

Ann Coulter 9/11 column[edit]

Two days after the 9/11 attacks, National Review published a column by far-right provocateur Ann Coulter where she wrote of Muslims, "This is no time to be precious about locating the exact individuals directly involved in this particular terrorist attack. We should invade their countries, kill their leaders and convert them to Christianity. We weren’t punctilious about locating and punishing only Hitler and his top officers. We carpet-bombed German cities; we killed civilians. That’s war. And this is war."[66] National Review later called the column a "mistake" and fired Coulter as a contributing editor.[67]

References[edit]

- ^ "Garrett Bewkes". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Total Circulation for Consumer Magazines". Alliance for Audited Media.

- ^ a b c d e f Perlstein, Rick (April 11, 2017). "I thought I understood the American Right". New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Byers, Dylan. "National Review, conservative thinkers stand against Donald Trump". CNN. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, David (September 24, 2017). "The Conservative Mind". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ Advertising Media Kit, National Review Online.

- ^ Nash, George H. (1976, 2006). The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. ISI Books: Wilmington, DE, pp. 186–93.

- ^ Nash, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. pp. 186–93.

- ^ a b Frohnen, Bruce, Jeremy Beer, and Jeffrey O. Nelson (2006) American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia. ISI Books, Wilmington, DE, pp. 186–88

- ^ Bogus, Carl T. (2011). Buckley: William F. Buckley Jr. and the Rise of American Conservatism. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781608193554.

- ^ Gregory L. Schneider. ed. (2003). Conservatism in America since 1930: a reader. NYU Press. pp. 195ff. ISBN 9780814797990.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Our Mission Statement, National Review Online, November 19, 1955

- ^ John P. Diggins, "Buckley's Comrades: The Ex-Communist as Conservative," Dissent July 1975, Vol. 22 Issue 4, pp. 370–86

- ^ Kevin Smant, "Whither Conservatism? James Burnham and 'National Review,' 1955–1964," Continuity, 1991, Issue 15, pp. 83–97; Smant, Principles and Heresies: Frank S. Meyer and the Shaping of the American Conservative Movement (2002) pp. 33–66

- ^ Golden Days Archived May 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, National Review Online, October 27, 2005.

- ^ Buckley, William (19 November 1955). "Our Mission Statement". National Review Online. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Frohnen, Bruce, Jeremy Beer, and Jeffrey O. Nelson, eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia. (2006) pp. 601–04

- ^ Roger Chapman, Culture wars: an encyclopedia of issues, viewpoints, and voices (2009) vol. 1 p. 58

- ^ A Personal Retrospective Archived October 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, National Review Online, August 9, 2004

- ^ Buckley, William F. (August 24, 1957). "Why the South Must Prevail" (PDF). National Review. 4. pp. 148–49. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ Quoted in John B. Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (2001) p. 138

- ^ Laura Kalman, Right Star Rising: A New Politics, 1974–1980 (2010) p. 23

- ^ Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives pp. 283–87

- ^ William F. Buckley Jr. "Goldwater, the John Birch Society, and Me". Commentary. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ^ "Nationalreview.com".

- ^ Archibald, George (October 25, 1985). "Jury begged not to let Buckley 'punish and destroy' Spotlight" (PDF). The Washington Times. Washington, D.C. p. 3-A. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ see Hanson, "The Home of Intellectual Populism Could Use Your Help" NRO 1 December, 2015

- ^ a b Hari, Johann, Titanic: Reshuffling the Deck Chairs on the National Review Cruise, in The New Republic, vol. 237, issue 1, July 2, 2007 (in MasterFile Premier (EbscoHost) (PDF) (subscription may be required)), p. 31

- ^ "Against Trump - National Review". January 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Mouth That Toured - National Review". July 17, 2018.

- ^ "Against the Trump Trade Bill - National Review". July 3, 2018.

- ^ "Keep the Pressure on Kim - National Review". May 2, 2018.

- ^ Beinart, Peter (July 13, 2018). "The 'To Be Sure' Conservatives".

- ^ "The Collapse of the Never-Trump ConservativesThe American Spectator". spectator.org.

- ^ "Why conservative magazines are more important than ever". Washington Post.

- ^ "Charles C. W. Cooke named Online editor at National Review". POLITICO. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "The Corner". Archived from the original on September 22, 2005.

- ^ "Bench Memos". Archived from the original on August 30, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ "Markos speaks", Ben Smith blog in The Politico, August 2, 2007.

- ^ "«".

- ^ "National Review 2017 Trans-Atlantic Crossing".

- ^ Shapiro, Gary. "An 'Encounter' With Conservative Publishing", "Knickerbocker" column, The New York Sun, December 9, 2005.

- ^ "Nationalreview.com Romney for President".

- ^ The Miami News, April 18, 1967. "A Trip into Idea Land with Bill Buckley". Retrieved October 17, 2011.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c d Jonah Goldberg (December 15, 2011). "The Editorial – My Take". Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ The Editors, December 11, 2007. "Romney for President".CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Editors (March 11, 2016). "Ted Cruz for President". Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ "George F. Will: Daily Beast bio". Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ "No, Hillary Clinton didn't feed the birther movement". PolitiFact. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Tumulty, Karen (June 12, 2008). "Will Obama's Anti-Rumor Plan Work?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Born in the U.S.A. - National Review". July 28, 2009.

- ^ "I Thought I Understood the American Right. Trump Proved Me Wrong". Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ The New Hate by Arthur Goldwag. p. 5.

- ^ Kirell, Andrew (February 21, 2018). "Dinesh D'Souza Mocked Shooting Survivors. Why Is He Still on the 'National Review' Masthead?". The Daily Beast. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Can National Review do more than preach to the choir?". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Mazza, Ed (February 22, 2018). "Chris Evans Shreds Right-Wing 'Pile Of Trash' Who Mocked School Shooting Survivors". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Bump, Philip (December 14, 2015). "Why this National Review global temperature graph is so misleading". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ O'Connor, Lydia (December 15, 2015). "This Is How Climate Change Deniers Are Tricking You". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "One chart shows how climate change deniers are skewing statistics to fit their view". Business Insider. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "No Data Manipulation at NOAA - FactCheck.org". FactCheck.org. February 9, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "How the blogosphere spread and amplified the Daily Mail's unsupported allegations of climate data manipulation". Climate Feedback. March 27, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Is National Review doomed?". January 30, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ "Opinion | Whatever happened to Michael Mann's defamation suit? (2017 edition)". Washington Post. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "Climate researcher's defamation suit about insulting columns is on". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/08/13/media-and-rights-organizations-defend-national-review-et-al-against-michael-mann/

- ^ "Weapons of Mass Deception by Sheldon Rampton, John Stauber | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. pp. 145–146. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ "National Review Cans Columnist Ann Coulter". The Washington Post. 2001.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allitt, Patrick. The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History (2010) excerpt and text search

- Bogus, Carl T. Buckley: William F. Buckley Jr. and the Rise of American Conservatism (2011)

- Critchlow, Donald T. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the Right Made Political History (2007)

- Frisk, David B. If Not Us, Who?: William Rusher, National Review, and the Conservative Movement (2011)

- Frohnen, Bruce et al. eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006) ISBN 1-932236-44-9

- Hart, Jeffrey. The Making of the American Conservative Mind: The National Review and Its Times (2005), a view from the inside

- Judis, John B. William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (2001) ISBN 978-0-7432-1797-2

- Nash, George. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (2006; 1st ed. 1978)

- Schneider, Gregory. The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution (2009)

- Smant, Kevin J. Principles and Heresies: Frank S. Meyer and the Shaping of the American Conservative Movement (2002) (ISBN 1-882926-72-2)

External links[edit]

- Official website

- NRI, National Review Institute

- "President Honors Buckley at 50th Anniversary of National Review". White House. George W Bush. October 6, 2005.