American English

| American English | |

|---|---|

| Region | United States |

Native speakers | 225 million, all varieties of English in the United States (2010 census)[1] 25.6 million L2 speakers of English in the United States (2003) |

Early forms | |

| Latin (English alphabet) Unified English Braille[2] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-US[3][4] |

American English (AmE, AE, AmEng, USEng, en-US),[5] sometimes called United States English or U.S. English,[6][7] is the set of varieties of the English language native to the United States.[8]

English is the most widely spoken language in the United States and is the common language used by the federal government, to the extent that all laws and compulsory education are practiced in English. Although not an officially established language of the whole country, English is considered the de facto language and is given official status by 32 of the 50 state governments.[9][10] As an example, while both Spanish and English have equivalent status in the local courts of Puerto Rico, under federal law, English is the official language for any matters being referred to the United States district court for the territory.[11]

The use of English in the United States is a result of English and British colonization of the Americas. The first wave of English-speaking settlers arrived in North America during the 17th century, followed by further migrations in the 18th and 19th centuries. Since then, American English has developed into new dialects, in some cases under the influence of West African and Native American languages, German, Dutch, Irish, Spanish, and other languages of successive waves of immigrants to the United States.

American English varieties form a linguistic continuum of dialects more similar to each other than to English dialects of other countries, including some common pronunciations and other features found nationwide.[12] Any North American English accent perceived as free of noticeably local, ethnic, or cultural markers is popularly called "General" or "Standard" American, a fairly uniform standard of broadcast mass media and the highly educated. Otherwise, according to Labov, with the major exception of Southern American English, regional accents throughout the country are not yielding to this standard,[13] and historical and present linguistic evidence does not support the notion of there being one single "mainstream" American accent.[14][15] On the contrary, the sound of American English continues to evolve, with some local accents disappearing, but several larger regional accents emerging.[16]

Contents

Varieties[edit]

While written American English is largely standardized across the country and its dialects are mutually intelligible, there are several recognizable regional and ethnic accents as well as some vocabulary differences.

Regional accents[edit]

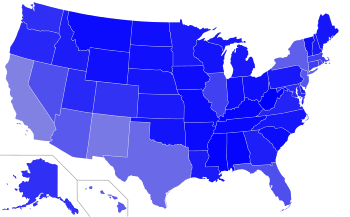

| The map above shows the major regional dialects of American English (in all caps) plus smaller and more local dialects, as demarcated primarily by Labov et al.'s The Atlas of North American English,[17] as well as the related Telsur Project's regional maps. Any region may also contain speakers of a "General American" accent that resists the marked features of their region. Furthermore, this map does not account for speakers of ethnic or cultural varieties (such as African-American English, Chicano English, Cajun English, etc.). | |

The regional sounds of present-day American English are reportedly engaged in a complex phenomenon of "both convergence and divergence": some accents are homogenizing and levelling, while others are diversifying and deviating further away from one another.[18]

Great Lakes accents, Chicago being the largest city with these speakers, tend to front the /ɑː/ vowel in the mouth and tense the short-a vowel wholesale, triggering a series of other vowel shifts in the more innovative accents of the region, which linguists call the "Inland North".[19] Great Lakes accents share that first feature with Boston accents. Both dialects, including the larger Eastern New England dialect of which Boston is the main hub, also show a back tongue positioning of: the /uː/ vowel (to [u]) and the /aʊ/ vowel (to [ɑʊ~äʊ]).[20] In the Northern U.S., from northern New England across the Great Lakes to Minnesota, the /ɑːr/ sound tends to move forward,[21] for example appearing four times in the stereotypical Boston shibboleth Park the car in Harvard Yard.[22] Boston, Pittsburgh, Upper Midwestern, and Western accents all merge the vowels of cot versus caught,[23] a feature rapidly expanding throughout the whole country; however, a Northeastern coastal corridor passing through Rhode Island, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore typically preserves a cot–caught distinction,[24] as depicted in popular humorous spellings of the caught vowel, as in tawk and cawfee, which intend to represent it being tense and diphthongal.[25] Eastern New England and New York City accents are the only American regional dialects with some strong degree of r-dropping (or non-rhoticity) in words like store, far, and weird,[26] though this was also once common in old Plantation Southern accents. New York City and Philadelphia/Baltimore accents are the only regions to split the short-a vowel into two distinct phonemes, using different a pronunciations for example in gap versus gas.[27]

The most marked accents of the country are New York City and Southern accents. Southern speech is defined by the /aɪ/ vowel losing its gliding quality to approach [aː~äː], the initiation event for a complicated Southern vowel shift, including a "Southern drawl" that makes short front vowels into distinct-sounding gliding vowels.[28] The strongest Southern sub-varieties exist in southern Appalachia and certain areas of Texas. Non-Southern Americans tend to stereotype Southern accents negatively, as "hick", "hillbilly", or "country" accents,[29] while Southerners themselves tend to have mixed judgments of their own accents, including positive associations of easygoingness and humility.[30] Southern accents, plus those spoken in the "Midland" (the vast band between the traditional dialect regions of the North and the South), tend to front the vowels of GOOSE, GOAT, MOUTH, and STRUT.

Below, nine major American English regional accents are defined by their particular combinations of certain characteristics:

| Accent name | Most populous urban center | Strong /aʊ/ fronting | Strong /oʊ/ fronting | Strong /uː/ fronting | Strong /ɑːr/ fronting | Cot–caught merger | Pin–pen merger | /æ/ raising system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inland Northern | Chicago | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | general |

| Mid-Atlantic States | Philadelphia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | split |

| Midland | Indianapolis | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mixed | Mixed | pre-nasal |

| New York City | New York City | Yes | No | No[31] | No | No | No | split |

| North-Central (Upper Midwestern) | Minneapolis | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | pre-nasal (pre-velar) |

| Northern New England | Boston | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | pre-nasal |

| Southern | Houston | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mixed | Yes | Southern |

| Western | Los Angeles | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | pre-nasal |

| Western Pennsylvania | Pittsburgh | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Mixed | pre-nasal |

General American[edit]

In 2010, William Labov noted that Great Lakes, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Western accents have undergone "vigorous new sound changes" since the mid-nineteenth century onwards, so they "are now more different from each other than they were fifty or a hundred years ago". [32] However, a General American sound system also has some controversial degree of influence, for example, gradually ousting local accents in urban areas of the South and at least some in the Inland North. Rather than one particular accent, "General American" can be defined as any American accent that does not incorporate features associated with some particular region, ethnicity, or socioeconomic group. General American features are embraced most by Americans who are highly educated or in the most formal contexts, and regional accents with the most "General American" native features include North Midland, Western New England. and Western accents. Typical General American features include rhoticity, the father–bother merger, Mary–marry–merry merger, and pre-nasal "short a" tensing.[note 1]

Other varieties[edit]

Although no longer region-specific,[33] African-American Vernacular English, which remains the native variety of most working- and middle-class African Americans, has a close relationship to Southern dialects and has greatly influenced everyday speech of many Americans, including hip hop culture. Hispanic and Latino Americans have also developed native-speaker varieties of English. The best-studied Latino Englishes are Chicano English, spoken in the West and Midwest, and New York Latino English, spoken in the New York metropolitan area. Additionally, ethnic varieties such as Yeshiva English and "Yinglish" are spoken by some American Jews, Cajun Vernacular English by some Cajuns in southern Louisiana, Pennsylvania Dutch English by some Pennsylvania Dutch in Pennsylvania and the Midwest, and American Indian Englishes have been documented among diverse Indian tribes. The island state of Hawaii, though primarily English-speaking, is also home to a creole language known commonly as Hawaiian Pidgin, and some Hawaii residents speak English with a Pidgin-influenced accent.

Phonology[edit]

Compared with English as spoken in England, North American English[34] is more homogeneous, and any North American accent that exhibits a majority of the most common phonological features is known as "General American". This section mostly refers to such widespread or mainstream pronunciation features that characterize American English.

Studies on historical usage of English in both the United States and the United Kingdom suggest that spoken American English did not simply deviate away from period British English, but retained certain now-archaic features contemporary British English has since lost.[35] One of these is the rhoticity common in most American accents, because in the 17th century, when English was brought to the Americas, most English in England was also rhotic. The preservation of rhoticity has been further supported by the influences of Hiberno-English, West Country English and Scottish English.[36] In most varieties of North American English, the sound corresponding to the letter ⟨r⟩ is a postalveolar approximant [ɹ̠] or retroflex approximant [ɻ] rather than a trill or tap (as often heard, for example, in the English accents of Scotland or India). A unique "bunched tongue" variant of the approximant r sound is also associated with the United States, and seems particularly noticeable in the Midwest and South.[37]

Traditionally, the "East Coast" comprises three or four major linguistically distinct regions, each of which possesses English varieties both distinct from each other as well as quite internally diverse: New England, the New York metropolitan area, the Mid-Atlantic states (centering on Philadelphia and Baltimore), and the Southern United States. The only traditionally r-dropping (or non-rhotic) regional accents of American English are all spoken along the Atlantic Coast and parts of the Gulf Coast (particularly still in Louisiana), because these areas were in close historical contact with England and imitated prestigious varieties of r-dropping London (a feature now widespread throughout most of England) at a time when they were undergoing changes.[39] Today, non-rhoticity is confined in the United States to the accents of eastern New England, New York City, older speakers of the former plantation South, and African-American Vernacular English (though the vowel-consonant cluster found in "bird", "work", "hurt", "learn", etc. usually retains its r pronunciation, even in these non-rhotic accents). Other than these few varieties, American accents are rhotic, pronouncing every instance of the ⟨r⟩ sound.

Many British accents have evolved in other ways compared to which General American English has remained relatively more conservative, for example, regarding the typical southern British features of a trap–bath split, fronting of /oʊ/, and H-dropping, none of which typical American accents show. The innovation of /t/ glottaling, which does occur before a consonant (including a syllabic coronal nasal consonant, like in the words button or satin) and word-finally in General American, additionally occurs variably between vowels in British English. On the other hand, General American is more innovative than the dialects of England, or English elsewhere in the world, in a number of its own ways:

- The merger of /ɑ/ and /ɒ/, making father and bother rhyme. This change, known as the father–bother merger is in a transitional or completed stage nearly universally in North American English. Exceptions are in northeastern New England English, such as the Boston accent, New York accent, and Mid-Atlantic States accents, and many Southern accents, prominently including New Orleans accents.[clarification needed][40][41]

- About half of all Americans merge of the vowels /ɑ/ and /ɔ/. This is the so-called cot–caught merger, where words like cot and caught are homophones. This change has occurred most firmly in eastern New England (Boston area), Greater Pittsburgh, and the whole western half of the country.[42]

- For speakers who do not merge caught and cot, the lot–cloth split has taken hold. This change took place prior to the unrounding of the cot. It is the result of the lengthening and raising of the cot vowel, merging with the caught vowel in many cases before voiceless fricatives (as in cloth, off), which is also found in some varieties of British English, as well as before /ŋ/ (as in strong, long), usually in gone, often in on, and irregularly before /ɡ/ (log, hog, dog, fog).

- The strut vowel, rather than the lot or thought vowel, is used in the function words was, of, from, what, everybody, nobody, somebody, anybody, and, for some speakers, because and want, when stressed.[43][44][45][46]

- Vowel mergers before intervocalic /ɹ/: The Mary–marry–merry, serious–Sirius, and hurry–furry mergers are found in most American English dialects. However, exceptions exist primarily along the east coast.

- Americans vary slightly in their pronunciations of R-colored vowels—such as those in /ɛəɹ/ and /ɪəɹ/—sometimes monophthongizing towards [ɛɹ] and [ɪɹ] or tensing towards [eɪɹ] and [i(ə)ɹ] respectively, causing pronunciations like [peɪɹ] for pair/pear and [piəɹ] for peer/pier.[47] Also, /jʊər/ is often reduced to [jɚ], so that cure, pure, and mature may all end with the sound [ɚ], thus rhyming with blur and sir. The word sure is also part of this rhyming set as it is commonly pronounced [ʃɚ].

- Dropping of /j/ is much more extensive than in most of England. In most North American accents, /j/ is dropped after all alveolar and interdental consonants (i.e. everywhere except after /p/, /b/, /f/, /h/, /k/, and /m/) so that new, duke, Tuesday, presume are pronounced [nu], [duk], [ˈtuzdeɪ], [pɹɪˈzum].

- /æ/ tensing in environments that vary widely from accent to accent. With most American speakers, for whom the phoneme /æ/ operates under a somewhat continuous system, /æ/ has both a tense and a lax allophone (with a kind of "continuum" of possible sounds between those two extremes, rather than a definitive split). In these accents, /æ/ is overall realized before nasal stops as more tense (approximately [eə̯]), while other environments are more lax (approximately the standard [æ]); for example, note the vowel sound in [mæs] for mass, but [meə̯n] for man). In some American accents, though, specifically those from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City, [æ] and [eə̯] are entirely separate (or "split") phonemes, for example, in planet [pɫænɪ̈t̚] vs. plan it [pɫeənɪ̈t̚]. This is often called the Mid-Atlantic split-a system. Note that these vowels move in the opposite direction in the mouth compared to the backed British "broad A"; this phenomenon has been noted as related to the increasingly rare phenomenon of older speakers of the eastern New England (Boston) area for whom /æ/ changes to /ɑ/ before /f/, /s/, /θ/, /ð/, /z/, /v/ alone or when preceded by a homorganic nasal. For the purposes of the chart below, [eə] represents a very tense vowel, [ɛə] a somewhat tense (or intermediate) vowel, and [æ] a non-tense (or lax) vowel, and the symbol "~" represents a continuous system in which the vowel may variably waver between two pronunciations.

| /æ/ raising in North American English[48] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | Dialect | ||||||||||||

| Consonant after /æ/ | Syllable type | Example words | New York City & New Orleans | Baltimore & Philadelphia | Eastern New England | General American, Midland U.S., & Western U.S. | Canadian, Northwestern U.S., & Upper Midwestern U.S. | Southern U.S. & African American Vernacular | Great Lakes | ||||

| /r/ | Open |

arable, arid, baron, barrel, barren, carry, carrot, chariot, charity, clarity, Gary, Harry, Larry, marionette, maritime, marry, marriage, paragon, parent, parish, parody, parrot, etc.; this feature is determined by the presence or absence of the Mary-marry-merry merger |

[æ] | [æ~ɛə] | [ɛə] | ||||||||

| /m/, /n/ | Closed |

Alexander, answer, ant, band, can (the noun), can't, clam, dance, ham, hamburger, hand, handy, man, manly, pants, plan, planning, ranch, sand, slant, tan, understand, etc.; in Philadelphia, began, ran, and swam alone remain lax |

[eə] | [æ~eə] | [æ~ɛə] | [ɛə~eə] | [eə] | ||||||

| Open |

amity, animal, can (the verb), Canada, ceramic, family (varies by speaker),[49], gamut, hammer, janitor, manager, manner, Montana, panel, planet, profanity, salmon, Spanish, etc. |

[æ] | |||||||||||

| /ɡ/ | Closed |

agriculture, bag, crag, drag, flag, magnet, rag, sag, tag, tagging, etc. |

[eə] | [æ] | [æ] | [æ~eə] | [æ~ɛə] | [æ~eə] | |||||

| Open |

agate, agony, dragon, magazine, ragamuffin, etc. |

[æ] | |||||||||||

| /b/, /d/, /dʒ/, /ʃ/, /v/, /z/, /ʒ/ | Closed |

absolve, abstain, add, ash, as, bad, badge, bash, cab, cash, clad, crag, dad, drab, fad, flash, glad, grab, had, halve (varies by speaker), jazz (varies by speaker), kashmir, mad, magnet, pad, plaid, rag, raspberry, rash, sad, sag, smash, splash, tab, tadpole, trash, etc. In NYC, this environment, particularly, /v/ and /z/, has a lot of variance and many exceptions to the rules. In Philadelphia, bad, mad, and glad alone in this set become tense. Similarly, in New York City, the /dʒ/ set is often tense even in open syllables (magic, imagine, etc.) |

[eə] | [æ~ɛə] | [æ] | ||||||||

| /f/, /s/, /θ/ | Closed |

ask, bask, basket, bath, brass, casket, cast, class, craft, crass, daft, drastic, glass, grass, flask, half, last, laugh, laughter, mask, mast, math, pass, past, path, plastic, task, wrath, etc. |

[eə] | ||||||||||

| All other consonants |

act, agony, allergy, apple, aspirin, athlete, avid, back, bat, brat, café, cafeteria, cap, cashew, cat, Catholic, chap, clap, classy, diagonal, fashion, fat, flap, flat, gap, gnat, latch, magazine, mallet, map, mastiff, match, maverick, Max, pack, pal, passive, passion, pat, patch, pattern, rabid, racket, rally, rap, rat, sack, sat, Saturn, savvy, scratch, shack, slack, slap, tackle, talent, trap, travel, wrap, etc. |

[æ] | |||||||||||

Footnotes

| |||||||||||||

- Flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to alveolar tap [ɾ] before unstressed vowels (as in "butter" [ˈbʌɾəɹ], "party" [ˈpɑɹɾi]) and syllabic /l/ ("bottle" [ˈbɑɾəɫ]), as well as at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel ("what else" [wʌˈɾɛɫs], "whatever" [wʌˈɾɛvəɹ]). Thus, for most speakers, pairs such as ladder/latter, metal/medal, and coating/coding are pronounced the same, except with the stressed /aɪ/ (see below).

- Canadian raising of /aɪ/: many speakers split the sound /aɪ/ based on its presence before either a voiceless or voiced consonant, so that in writer it is pronounced [ʌɪ] but in rider it is pronounced [äɪ] (because [t] is a voiceless consonant while [d] is voiced). This is a form of Canadian raising but, unlike more extreme forms of that process, does not affect /aʊ/. In many areas and idiolects, a distinction between what elsewhere become homophones through this process is maintained by vowel lengthening in the vowel preceding the formerly voiced consonant, e.g., [ˈɹʌɪɾɚ] for "writer" as opposed to [ˈɹäɪɾɚ] for "rider".

- Many speakers in the Inland North, North Central American English, and Philadelphia dialect areas raise /aɪ/ before voiced consonants in certain words as well, particularly [d], [g] and [n]. Hence, words like tiny, spider, cider, tiger, dinosaur, cyber-, beside, idle (but sometimes not idol), and fire may contain a raised nucleus. The use of [ʌɪ] rather than [aɪ] in such words is unpredictable from phonetic environment alone, though it may have to do with their acoustic similarity to other words that do contain [ʌɪ] before a voiceless consonant, per the traditional Canadian-raising system. Hence, some researchers have argued that there has been a phonemic split in these dialects; the distribution of the two sounds is becoming more unpredictable among younger speakers.[50]

- L-velarization: England's typical distinction between a "clear L" (i.e. [l]) and a "dark L" (i.e. [ɫ] or sometimes even [ʟ]) is much less noticeable in nearly all dialects of American English; it is often altogether absent.[51] Instead, most U.S. speakers pronounce all "L" sounds with a tendency to be "dark", meaning with some degree of velarization.[52] The only notable exceptions to this are in some Spanish-influenced U.S. English varieties (such as East Coast Latino English, which typically shows a clear "L" in syllable onsets); in New York City English, where the /l/ is clear in prevocalic positions;[53] and in older, moribund Southern speech of the U.S., where "L" is clear in an intervocalic environment between front vowels.[54]

- Both intervocalic /nt/ and /n/ may commonly be realized as [ɾ̃] or simply [n], making winter and winner homophones in fast or non-careful speech.

- The vowel /ɪ/ in unstressed syllables generally merges with /ə/ (weak-vowel merger), so effect is pronounced like affect.

Some mergers found in most varieties of both American and British English include:

- Horse–hoarse merger, making the vowels /ɔ/ and /o/ before 'r' homophones, with homophonous pairs like horse/hoarse, corps/core, for/four, morning/mourning, war/wore, etc. homophones.

- Wine–whine merger, making pairs like wine/whine, wet/whet, Wales/whales, wear/where, etc. homophones, in most cases eliminating /ʍ/, the voiceless labiovelar fricative. Many older varieties of southern and western American English still keep these distinct, but the merger appears to be spreading.

Vocabulary[edit]

The process of coining new lexical items started as soon as English-speaking British-American colonists began borrowing names for unfamiliar flora, fauna, and topography from the Native American languages.[55] Examples of such names are opossum, raccoon, squash, moose (from Algonquian),[55] wigwam, and moccasin. The languages of the other colonizing nations also added to the American vocabulary; for instance, cookie, from Dutch; kindergarten from German,[56] levee from French; and rodeo from Spanish.[57][58][59][60] Landscape features are often loanwords from French or Spanish, and the word corn, used in England to refer to wheat (or any cereal), came to denote the maize plant, the most important crop in the U.S.

Most Mexican Spanish contributions came after the War of 1812, with the opening of the West, like ranch (now a common house style). Due to the Mexican culinary influence, many Spanish words are incorporated in general use when talking about certain popular dishes: cilantro (instead of coriander), queso, tacos, quesadillas, enchiladas, tostadas, fajitas, burritos, and guacamole. These words don't really have an English equivalent and are found at popular restaurants such as Chipotle [61] or Taco Bell [62]New forms of dwelling created new terms (lot, waterfront) and types of homes like log cabin, adobe in the 18th century; apartment, shanty in the 19th century; project, condominium, townhouse, mobile home in the 20th century; and parts thereof (driveway, breezeway, backyard).[citation needed] Industry and material innovations from the 19th century onwards provide distinctive new words, phrases, and idioms through railroading (see further at rail terminology) and transportation terminology, ranging from types of roads (dirt roads, freeways) to infrastructure (parking lot, overpass, rest area), to automotive terminology often now standard in English internationally.[63] Already existing English words—such as store, shop, lumber—underwent shifts in meaning; others remained in the U.S. while changing in Britain. Science, urbanization, and democracy have been important factors in bringing about changes in the written and spoken language of the United States. [64] From the world of business and finance came new terms (merger, downsize, bottom line), from sports and gambling terminology came, specific jargon aside, common everyday American idioms, including many idioms related to baseball. The names of some American inventions remained largely confined to North America (elevator, gasoline) as did certain automotive terms (truck, trunk).

New foreign loanwords came with 19th and early 20th century European immigration to the U.S.; notably, from Yiddish (chutzpah, schmooze) and German (hamburger, wiener).[65][66] A large number of English colloquialisms from various periods are American in origin; some have lost their American flavor (from OK and cool to nerd and 24/7), while others have not (have a nice day, for sure);[67][68] many are now distinctly old-fashioned (swell, groovy). Some English words now in general use, such as hijacking, disc jockey, boost, bulldoze and jazz, originated as American slang.

American English has always shown a marked tendency to use anthimeria and nouns are often used as verbs.[69] Examples of nouns that are now also verbs are interview, advocate, vacuum, lobby, pressure, rear-end, transition, feature, profile, hashtag, head, divorce, loan, estimate, X-ray, spearhead, skyrocket, showcase, bad-mouth, vacation, major, and many others. Compounds coined in the U.S. are for instance foothill, landslide (in all senses), backdrop, teenager, brainstorm, bandwagon, hitchhike, smalltime, and a huge number of others. Other compound words have been founded based on industrialization and the wave of the automobile: five-passenger car, four-door sedan, two-door sedan, and station-wagon (called an estate car in England). [70] Some are euphemistic (human resources, affirmative action, correctional facility). Many compound nouns have the verb-and-preposition combination: stopover, lineup, tryout, spin-off, shootout, holdup, hideout, comeback, makeover, and many more. Some prepositional and phrasal verbs are in fact of American origin (win out, hold up, back up/off/down/out, face up to and many others).[71]

Noun endings such as -ee (retiree), -ery (bakery), -ster (gangster) and -cian (beautician) are also particularly productive in the U.S.[69] Several verbs ending in -ize are of U.S. origin; for example, fetishize, prioritize, burglarize, accessorize, weatherize, etc; and so are some back-formations (locate, fine-tune, curate, donate, emote, upholster and enthuse). Among syntactical constructions that arose are outside of, headed for, meet up with, back of, etc. Americanisms formed by alteration of some existing words include notably pesky, phony, rambunctious, buddy, sundae, skeeter, sashay and kitty-corner. Adjectives that arose in the U.S. are, for example, lengthy, bossy, cute and cutesy, punk (in all senses), sticky (of the weather), through (as in "finished"), and many colloquial forms such as peppy or wacky.

A number of words and meanings that originated in Middle English or Early Modern English and that have been in everyday use in the United States have since disappeared in most varieties of British English; some of these have cognates in Lowland Scots. Terms such as fall ("autumn"), faucet ("tap"), diaper ("nappy"), candy ("sweets"), skillet, eyeglasses, and obligate are often regarded as Americanisms. Fall for example came to denote the season in 16th century England, a contraction of Middle English expressions like "fall of the leaf" and "fall of the year".[72] Gotten (past participle of get) is often considered to be largely an Americanism.[73] Other words and meanings were brought back to Britain from the U.S., especially in the second half of the 20th century; these include hire ("to employ"), I guess (famously criticized by H. W. Fowler), baggage, hit (a place), and the adverbs overly and presently ("currently"). Some of these, for example, monkey wrench and wastebasket, originated in 19th century Britain. The adjectives mad meaning "angry", smart meaning "intelligent", and sick meaning "ill" are also more frequent in American (and Irish) English than British English.[74][75][76]

Linguist Bert Vaux created a survey, completed in 2003, polling English speakers across the United States about their specific everyday word choices, hoping to identify regionalisms.[77] The study found that most Americans prefer the term sub for a long sandwich, soda (but pop in the Great Lakes region and generic coke in the South) for a sweet and bubbly soft drink,[78] you or you guys for the plural of you (but y'all in the South), sneakers for athletic shoes (but often tennis shoes outside the Northeast), and shopping cart for a cart used for carrying supermarket goods.

Differences between British and American English[edit]

| Comparison of American and British English |

|---|

| Computing |

| Grammar |

|

|

| Orthography |

| Speech |

| Vocabulary |

|

|

| Works |

|

|

American English and British English (BrE) often differ at the levels of phonology, phonetics, vocabulary, and, to a much lesser extent, grammar and orthography. The first large American dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language, known as Webster's Dictionary, was written by Noah Webster in 1828, codifying several of these spellings.

Differences in grammar are relatively minor, and do not normally affect mutual intelligibility; these include: different use of some auxiliary verbs; formal (rather than notional) agreement with collective nouns; different preferences for the past forms of a few verbs (for example, AmE/BrE: learned/learnt, burned/burnt, snuck/sneaked, dove/dived) although the purportedly "British" forms can occasionally be seen in American English writing as well; different prepositions and adverbs in certain contexts (for example, AmE in school, BrE at school); and whether or not a definite article is used, in very few cases (AmE to the hospital, BrE to hospital; contrast, however, AmE actress Elizabeth Taylor, BrE the actress Elizabeth Taylor). Often, these differences are a matter of relative preferences rather than absolute rules; and most are not stable, since the two varieties are constantly influencing each other,[79] and American English is not a standardized set of dialects.

Differences in orthography are also minor. The main differences are that American English usually uses spellings such as flavor for British flavour, fiber for fibre, defense for defence, analyze for analyse, license for licence, catalog for catalogue and traveling for travelling. Noah Webster popularized such spellings in America, but he did not invent most of them. Rather, "he chose already existing options [...] on such grounds as simplicity, analogy or etymology".[80] Other differences are due to the francophile tastes of the 19th century Victorian era Britain (for example they preferred programme for program, manoeuvre for maneuver, cheque for check, etc.).[81] AmE almost always uses -ize in words like realize. BrE prefers -ise, but also uses -ize on occasion (see Oxford spelling).

There are a few differences in punctuation rules. British English is more tolerant of run-on sentences, called "comma splices" in American English, and American English requires that periods and commas be placed inside closing quotation marks even in cases in which British rules would place them outside. American English also favors the double quotation mark over single.[82]

Vocabulary differences vary by regions. For example, autumn is used more commonly in England, whereas fall is more common in American English. Some other differences include: aerial (England) vs. antenna, biscuit (England) vs. cookie/cracker, car park (England) vs. parking lot, caravan (England) vs. trailer, city centre (England) vs. downtown, flat (England) vs. apartment, fringe (England) vs. bangs, and holiday (England) vs. vacation. [83]

AmE sometimes favors words that are morphologically more complex, whereas BrE uses clipped forms, such as AmE transportation and BrE transport or where the British form is a back-formation, such as AmE burglarize and BrE burgle (from burglar). However, while individuals usually use one or the other, both forms will be widely understood and mostly used alongside each other within the two systems.

British English also differs from American English in that "schedule" can be pronounced with either [sk] or [ʃ].[84]

See also[edit]

- Dictionary of American Regional English

- List of English words from indigenous languages of the Americas

- IPA chart for English

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Canadian English

- North American English

- International English

- Received Pronunciation

- Transatlantic accent

- American and British English spelling differences

Notes[edit]

- ^ Dialects are considered "rhotic" if they pronounce the r sound in all historical environments, without ever "dropping" this sound. The father–bother merger is the pronunciation of the unrounded /ɒ/ vowel variant (as in cot, lot, bother, etc.) the same as the /ɑː/ vowel (as in spa, haha, Ma), causing words like con and Kahn and like sob and Saab to sound identical, with the vowel usually realized in the back or middle of the mouth as [ɑ~ä]. Finally, most of the U.S. participates in a continuous nasal system of the "short a" vowel (in cat, trap, bath, etc.), causing /æ/ to be pronounced with the tongue raised and with a glide quality (typically sounding like [ɛə]) particularly when before a nasal consonant; thus, mad is [mæd], but man is more like [mɛən].

References[edit]

- ^ English (United States) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ^ "Unified English Braille (UEB)". Braille Authority of North America (BANA). 2 November 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "English"; IANA language subtag registry; named as: en; publication date: 16 October 2005; retrieved: 11 January 2019.

- ^ "United States"; IANA language subtag registry; named as: US; publication date: 16 October 2005; retrieved: 11 January 2019.

- ^

en-USis the language code for U.S. English, as defined by ISO standards (see ISO 639-1 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-2) and Internet standards (see IETF language tag). - ^ Plichta, Bartlomiej, and Dennis R. Preston (2005). "The /ay/s Have It: The Perception of /ay/ as a North-South Stereotype in the United States English." Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 37.1: 107-130.

- ^ Zentella, A. C. (1982). Spanish and English in contact in the United States: The Puerto Rican experience. Word, 33(1-2), 41.

- ^ Crystal, David (1997). English as a Global Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53032-6.

- ^ Crawford, James (1 February 2012). "Language Legislation in the U.S.A." languagepolicy.net. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "U.S. English Efforts Lead West Virginia to Become 32nd State to Recognize English as Official Language". us-english.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "48 U.S. Code § 864 - Appeals, certiorari, removal of causes, etc.; use of English language | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ Kretzchmar, William A. (2004), Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W., eds., A Handbook of Varieties of English, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 262–263, ISBN 9783110175325

- ^ Labov, William (2010). "Chapter 1".The Politics of Language Change: Dialect Divergence in America. The University of Virginia Press. Pre-publication draft. p. 55.

- ^ Labov, William (2012). Dialect diversity in America: The politics of language change. University of Virginia Press. pp. 1-2.

- ^ Kretzchmar, William A. (2004), Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W., eds., A Handbook of Varieties of English, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, p. 262, ISBN 9783110175325

- ^ "Do You Speak American: What Lies Ahead". PBS. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:148)

- ^ Labov, William. 2012. Dialect diversity in America: the politics of language change. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:190)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:230)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:111)

- ^ Vorhees, Mara (2009). Boston. Con Pianta. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-74179-178-5.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:60)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:190)

- ^ "This phonemic and phonetic arrangement of the low back vowels makes Rhode Island more similar to New York City than to the rest of New England".Labov, Ash & Ash (2006:226)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137, 141)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:173)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:125)

- ^ Hayes, 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Hayes, 2013, p. vi, 39.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:107)

- ^ Labov, William (2010). The Politics of Language Change: Dialect Divergence in America. The University of Virginia Press. Pre-publication draft. p. 53-4.

- ^ Cf. Trudgill, p.42.

- ^ North American English (Trudgill, p. 2) is a collective term used for the varieties of the English language that are spoken in both the United States and Canada.

- ^ "What Is the Difference between Theater and Theatre?". Wisegeek.org. 2015-05-15. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ "Early Mainland Residues in Southern Hiberno-English". 20. doi:10.2307/25484343. JSTOR 25484343. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ A Handbook of Varieties of English, Bernd Kortmann & Edgar W. Schneider, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, p. 317.

- ^ Labov, p. 48.

- ^ Trudgill, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–37, 203–6, 234, 245–47, 339–40, 400, 419, 443, 576. ISBN 0-521-22919-7.

0-521-22919-7 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2), ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:171)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:61)

- ^ According to Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition.

- ^ "Want: meaning and definitions". Dictionary.infoplease.com. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "want. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000". Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 2008-01-09. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Want – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". M-w.com. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ J. C. Wells. Accents of English. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 481–482.

- ^ Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 182. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- ^ Trager, George L. (1940) One Phonemic Entity Becomes Two: The Case of 'Short A' in American Speech: 3rd ed. Vol. 15: Duke UP. 256. Print.

- ^ Freuhwald, Josef T. (November 11, 2007). "The Spread of Raising: Opacity, lexicalization, and diffusion". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Grzegorz Dogil, Susanne Maria Reiterer, and Walter de Gruyter, eds. (2009). "general+american"+"velarized" Language Talent and Brain Activity: Trends in Applied Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 299.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Wells (1982:490)

- ^ Wells, John C. (April 8, 1982). Accents of English: Vowel 3: Beyond the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. p. 515.

- ^ A Handbook of Varieties of English, Bernd Kortmann & Edgar W. Schneider, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, p. 319.

- ^ a b Principles of English etymology: The native element - Walter William Skeat. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ "You Already Know Some German Words!". Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ ""The history of Mexican folk foodways of South Texas: Street vendors, o" by Mario Montano". Repository.upenn.edu. 1992-01-01. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ What's in a Word?: Etymological Gossip about Some Interesting English Words - Robert M. Gorrell. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ The Pocket Gophers of the United States - Vernon Bailey. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ The American Language: A Preliminary Inquiry Into the Development of English ... - H. L. Mencken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ https://www.chipotle.com/#rewards-eligibility. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ https://www.tacobell.com/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ A few of these are now chiefly found, or have been more productive, outside the U.S.; for example, jump, "to drive past a traffic signal"; block meaning "building", and center, "central point in a town" or "main area for a particular activity" (cf. Oxford English Dictionary).

- ^ https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9117&context=gradschool_disstheses. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "The Maven's Word of the Day: gesundheit". Random House. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (2004). New-Dialect Formation: The Inevitability of Colonial Englishes.

- ^ "Definition of day noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Oup.com. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Definition of sure adjective from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Oup.com. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ a b Trudgill, p. 69.

- ^ http://www.theword.cz/inotherwords/american-vs-british-smackdown-station-wagon-vs-estate-car/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ British author George Orwell (in English People, 1947, cited in OED s.v. lose) criticized an alleged "American tendency" to "burden every verb with a preposition that adds nothing to its meaning (win out, lose out, face up to, etc.)".

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "fall". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ A Handbook of Varieties of English, Bernd Kortmann & Edgar W. Schneider, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, p. 115.

- ^ "angry". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "intelligent". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Definition of ill adjective from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Oald8.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Vaux, Bert and Scott Golder. 2003. The Harvard Dialect Survey Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.

- ^ Katz, Joshua (2013). "Beyond 'Soda, Pop, or Coke.' North Carolina State University.

- ^ Algeo, John (2006). British or American English?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37993-8.

- ^ Algeo, John. "The Effects of the Revolution on Language", in A Companion to the American Revolution. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. p.599

- ^ Peters, Pam (2004). The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62181-X, pp. 34 and 511.

- ^ "Punctuating Around Quotation Marks" (blog). Style Guide of the American Psychological Association. 2011. Retrieved 2015-03-21.

- ^ http://www.studyenglishtoday.net/british-american-english.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Jones, Daniel (1991). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425865.

Bibliography[edit]

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Bailey, Richard W. (2012). Speaking American: A History of English in the United States 20th-21st century usage in different cities

- Bartlett, John R. (1848). Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded As Peculiar to the United States. New York: Bartlett and Welford.

- Garner, Bryan A. (2003). Garner's Modern American Usage. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mencken, H. L. (1977) [1921]. The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States (4th ed.). New York: Knopf.

- History of American English

- Bailey, Richard W. (2004). "American English: Its origins and history". In E. Finegan & J. R. Rickford (Eds.), Language in the USA: Themes for the twenty-first century (pp. 3–17). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Finegan, Edward. (2006). "English in North America". In R. Hogg & D. Denison (Eds.), A history of the English language (pp. 384–419). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

| Look up American English in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Americanisms. |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about American English |

- Do You Speak American: PBS special

- Dialect Survey of the United States, by Bert Vaux et al., Harvard University.

- Linguistic Atlas Projects

- Phonological Atlas of North America at the University of Pennsylvania

- Speech Accent Archive

- Dictionary of American Regional English

- Dialect maps based on pronunciation

Countries.png/600px-Anglospeak(800px)Countries.png)