Resistor ladder

A resistor ladder is an electrical circuit made from repeating units of resistors. Two configurations are discussed below, a string resistor ladder and an R–2R ladder.

An R–2R ladder is a simple and inexpensive way to perform digital-to-analog conversion, using repetitive arrangements of precise resistor networks in a ladder-like configuration. A string resistor ladder implements the non-repetitive reference network.

Contents

String resistor ladder network (analog to digital conversion, or ADC)[edit]

A string of many, often equally dimensioned, resistors connected between two reference voltages is a resistor string ladder network. The resistors act as voltage dividers between the referenced voltages. Each tap of the string generates a different voltage, which can be compared with another voltage: this is the basic principle of a flash ADC (analog-to-digital converter). Often a voltage is converted to a current, enabling the possibility to use an R–2R ladder network.

- Disadvantage: for an n-bit ADC, the number of resistors grows exponentially, as resistors are required, while the R–2R resistor ladder only increases linearly with the number of bits, as it needs only resistors.

- Advantage: higher impedance values can be reached using the same number of components.

R–2R resistor ladder network (digital to analog conversion)[edit]

A basic R–2R resistor ladder network is shown in Figure 1. Bit an−1 (most significant bit, MSB) through bit a0 (least significant bit, LSB) are driven from digital logic gates. Ideally, the bit inputs are switched between V = 0 (logic 0) and V = Vref (logic 1). The R–2R network causes these digital bits to be weighted in their contribution to the output voltage Vout. Depending on which bits are set to 1 and which to 0, the output voltage (Vout) will have a corresponding stepped value between 0 and Vref minus the value of the minimal step, corresponding to bit 0. The actual value of Vref (and the voltage of logic 0) will depend on the type of technology used to generate the digital signals.[1]

For a digital value VAL, of a R–2R DAC with N bits and 0 V/Vref logic levels, the output voltage Vout is:

For example, if N = 5 (hence 2N = 32) and Vref = 3.3 V (typical CMOS logic 1 voltage), then Vout will vary between 0 volts (VAL = 0 = 000002) and the maximum (VAL = 31 = 111112):

with steps (corresponding to VAL = 1 = 000012)

The R–2R ladder is inexpensive and relatively easy to manufacture, since only two resistor values are required (or even one, if R is made by placing a pair of 2R in parallel, or if 2R is made by placing a pair of R in series). It is fast and has fixed output impedance R. The R–2R ladder operates as a string of current dividers, whose output accuracy is solely dependent on how well each resistor is matched to the others. Small inaccuracies in the MSB resistors can entirely overwhelm the contribution of the LSB resistors. This may result in non-monotonic behavior at major crossings, such as from 011112 to 100002. Depending on the type of logic gates used and design of the logic circuits, there may be transitional voltage spikes at such major crossings even with perfect resistor values. These can be filtered with capacitance at the output node (the consequent reduction in bandwidth may be significant in some applications). Finally, the 2R resistance is in series with the digital-output impedance. High-output-impedance gates (e.g., LVDS) may be unsuitable in some cases. For all of the above reasons (and doubtless others), this type of DAC tends to be restricted to a relatively small number of bits; although integrated circuits may push the number of bits to 14 or even more, 8 bits or fewer is more typical.

Accuracy of R–2R resistor ladders[edit]

Resistors used with the more significant bits must be proportionally more accurate than those used with the less significant bits; for example, in the R–2R network discussed above, inaccuracies in the bit-4 (MSB) resistors must be insignificant compared to R/32 (i.e., much better than 3%). Further, to avoid problems at the 100002-to-011112 transition, the sum of the inaccuracies in the lower bits must be significantly less than R/32. The required accuracy doubles with each additional bit: for 8 bits, the accuracy required will be better than 1/256 (0.4%). Within integrated circuits, high-accuracy R–2R networks may be printed directly onto a single substrate using thin-film technology, ensuring the resistors share similar electrical characteristics. Even so, they must often be laser-trimmed to achieve the required precision. Such on-chip resistor ladders for digital-to-analog converters achieving 16-bit accuracy have been demonstrated.[2] On a printed circuit board, using discrete components, resistors of 1% accuracy would suffice for a 5-bit circuit, however with bit counts beyond this the cost of ever increasing precision resistors becomes prohibitive. For a 10-bit converter, even using 0.1% precision resistors would not guarantee monotonicity of output. This being said, high resolution R-2R ladders formed from discrete components are sometimes used, the nonlinearity being corrected in software. One example of such approach can be seen in the Korad 3005 power supply.

Resistor ladder with unequal rungs[edit]

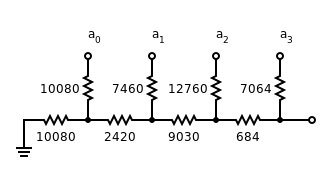

It is not necessary that each "rung" of the R–2R ladder use the same resistor values. It is only necessary that the "2R" value matches the sum of the "R" value plus the Thévenin-equivalent resistance of the lower-significance rungs. Figure 2 shows a linear 4-bit DAC with unequal resistors.

This allows a reasonably accurate DAC to be created from a heterogeneous collection of resistors by forming the DAC one bit at a time. At each stage, resistors for the "rung" and "leg" are chosen so that the rung value matches the leg value plus the equivalent resistance of the previous rungs. The rung and leg resistors can be formed by pairing other resistors in series or parallel in order to increase the number of available combinations. This process can be automated.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mixed analog and digital circuit diagrams. |

- ECE209: DAC Lecture Notes - Ohio State University

- EE247: D/A Converters - Berkeley University of California

- Simplified DAC/ADC Lecture Notes - University of Michigan

- Digital to Analog Converters (slides) - Georgia Tech

- Tutorial MT-014: String DACs and Fully-Decoded DACs - Analog Devices

- Tutorial MT-015: Binary DACs - Analog Devices

- Tutorial MT-016: Segmented DACs - Analog Devices

- Tutorial MT-018: Intentionally Nonlinear DACs - Analog Devices

- R2R Resistor Ladder Networks - BT Technologies

- R/2R Ladder Networks Application Note - TT Electronics