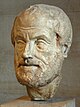

Aristotle's theory of universals

Aristotle's theory of universals is a classic solution to the problem of universals. Universals are types, properties, or relations that are common to their various instances. In Aristotle's view, universals exist only where they are instantiated; they exist only in things. Aristotle said that a universal is identical in each of its instances. All red things are similar in that there is the same universal, redness, in each thing. There is no Platonic Form of redness, standing apart from all red things; instead, each red thing has a copy of the same property, redness.

Overview[edit]

In Aristotle's view, universals can be instantiated multiple times. He states that one and the same universal, such as applehood, appears in every real apple. A common sense challenge would be to inquire what remains exactly the same in all these different things, since the theory is claiming that something remains the same. Stating that different deserts, such as the Sahara, the Atacama, and the Gobi, are all dry places is just to say that each place is the same (qualitatively) in terms of dryness. Aristotle is talking about a category of being here that is not a thing but a quality. A common defence of Aristotle's realism is therefore that we should not expect universals to behave like ordinary physical objects. To say the same universal, dryness, occurs simultaneously in all these places is no more strange than saying that each place is dry.

A second issue is whether Aristotelian universals are abstract: if they are, then the theory must deal with how to abstract the concept of redness from one or more red things. Aristotle argued that people form concepts and make generalisations in the manner of a young child, who is just on the verge of grasping a generic concept such as human being. In his view, the child is gathering his or her memories of various encounters with individual humans, searching for the essential similarity that stands out, on reflection, in every instance. Today, it might be said that one mentally extracts from each thing the quality that they all have in common. When the child grasps the concept of a human being, he or she has learnt to ignore the accidental details of each person's past experiences and individual differences, and has paid attention to the relevant quality that they all have in common, namely, humanity. In Aristotle's view, the universal humanity is a natural kind defined by the essential properties that all humans have in common.