Extraposition

Extraposition is a mechanism of syntax that alters word order in such a manner that a relatively "heavy" constituent appears to the right of its canonical position.[1] Extraposing a constituent results in a discontinuity and in this regard, it is unlike shifting, which does not generate a discontinuity. The extraposed constituent is separated from its governor by one or more words that dominate its governor. Two types of extraposition are acknowledged in theoretical syntax: standard cases where extraposition is optional and it-extraposition where extraposition is obligatory. Extraposition is motivated in part by a desire to reduce center embedding by increasing right-branching and thus easing processing, center-embedded structures being more difficult to process. Extraposition occurs frequently in English and related languages.

Contents

Examples[edit]

Standard cases of extrapostion are optional, although at times the extraposed version of the sentence is strongly preferred. The following pairs of sentences illustrate "normal" word order first followed by the same sentence with extraposition:

- a. Someone who we don't know left a message.

- b. Someone left a message who we don't know. - Extraposition of relative clause out of subject

- a. Susan said something that nobody expected more than once.

- b. Susan said something more than once that nobody expected. - Extraposition of relative clause out of object

- a. Some guy with red hair was there.

- b. Some guy was there with red hair. - Extraposition of prepositional phrase out of subject

- a. How frustrated with their kids are they?

- b. How frustrated are they with their kids? - Extraposition of prepositional phrase from predicative adjective phrase

- a. %What that was so entertaining actually happened?

- b. What actually happened that was so entertaining? - Extraposition of content clause from subject wh-element

- a. %What that upset everyone do you think they did?

- b. What do you think they did that upset everyone? - Extraposition of content clause from object wh-element

These examples illustrate a couple of basic facts about extraposition. One of these facts is that relatively "heavy" constituents are being extraposed (e.g.usually clauses and sometimes prepositional phrases). Another fact is that extraposition can occur out of subjects. This aspect of extraposition is unlike topicalization and wh-fronting, two other mechanisms that often generate discontinuities. Attempts to front expressions out of subjects fail in English. Another fact about extraposition is that sometimes it cannot occur beyond informationally heavy material.

- a. Some guy with red hair was talking excessively.

- b. *Some guy was talking excessively with red hair. - Failed attempt to extrapose prepositional phrase

This aspect of extraposition supports the insight that extraposed constituents should be informationally heavy. Extraposition likely fails in this case because with red hair cannot be construed as important information.

Clause bound[edit]

A further widely acknowledged fact about extraposition is that it is clause-bound. This aspect of extraposition is known as the Right Roof Constraint.[2] There is a "right roof" above which extraposition cannot occur. In other words, extraposition cannot occur out of an embedded clause:

- a. That we think that the idea is good is no secret.

- b. *That we think is no secret that the idea is good. - Failed attempt to extrapose out of a subject clause

- a. Someone who thinks that Romney will win was talking non-stop.

- b. *Someone who thinks was talking non-stop that Romney will win. - Failed attempt to extrapose out of a relative clause

- a. Before it was certain that it would rain, we were planning a picnic.

- b. *Before it was certain, we were planning a picnic that it would rain. - Failed attempt to extrapose out of an adjunct clause

This aspect of extraposition is unlike fronting discontinuities (topicialization and wh-fronting), which can easily front a constituent out of an (argument) clause, e.g.

- a. They mentioned that they like the coffee.

- b. What did they mention that they like. - Successful wh-fronting out of an object clause

but it is like scrambling discontinuities; scrambling cannot displace a constituent from one clause into another.

It-extraposition[edit]

The term "extraposition" is also used to denote similar structures in which it appears.[3] While certainly related to canonical cases, it-extraposition is different in at least one important respect. In cases of it-extraposition, extraposition is not optional, but rather it is obligatory, e.g.

- a. *It that I burned the potatoes was frustrating. - Failed sentence because extraposition is obligatory when it appears

- b. It was frustrating that I burned the potatoes.

- a. *Did it that that happened surprise you? - Failed sentence because extraposition is obligatory when it appears

- b. Did it surprise you that that happened?

- a. *We suggested it that we leave later than planned to them. - Failed sentence because extraposition is obligatory when it appears

- b. We suggested it to them that we leave later than planned.

- a. *Nobody believes it that Newt will get the nomination for a second. - Failed sentence because extraposition is obligatory when it appears

- a. Nobody believes it for a second that Newt will get the nomination.

Another aspect of it-extraposition that distinguishes it from canonical cases is that the extraposed constituent is usually a clause; it-extraposition cannot extrapose a prepositional phrase. This fact can be explained by appealing to the status of it as a cataphor. In other words, it is pro-form of a sort; its appearance pushes the clause that it stands for to the end of the sentence. Since prepositional phrases cannot appear in the position of a clause, it should not be surprising that prepositional phrases cannot be it-extraposed.

Motivation[edit]

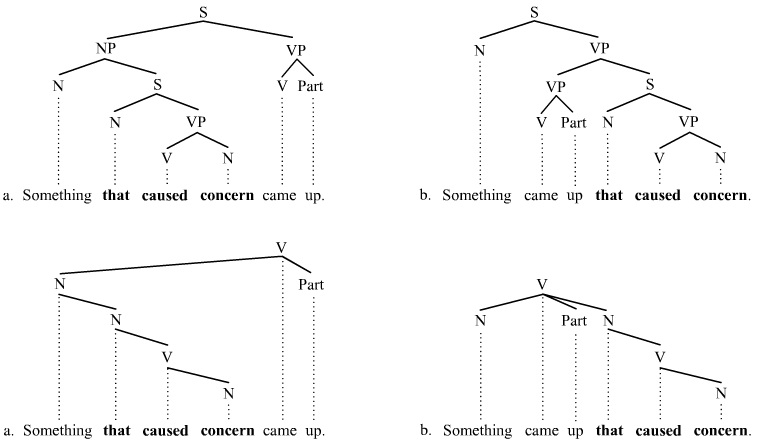

Extraposition is motivated at least in part by the desire to reduce processing load.[4][citation needed] When extraposition occurs, it inevitably reduces center embedding and thus increases right-branching. Right-branching structures in English are known to be easier to process. The extent to which extraposition increases right-branching is now illustrated using both a constituency-based analysis of a phrase structure grammar and a dependency-based analysis of a dependency grammar. The constituency-based trees appear first above the dependency-based trees:

The a-trees, which lack extraposition, extend down, whereas the b-trees, where extraposition is present, grow down and to the right. English, like many other languages, prefers to avoid trees that grow just down. Extraposition is one mechanism that increases rightward growth (shifting is another).

Theoretical analyses[edit]

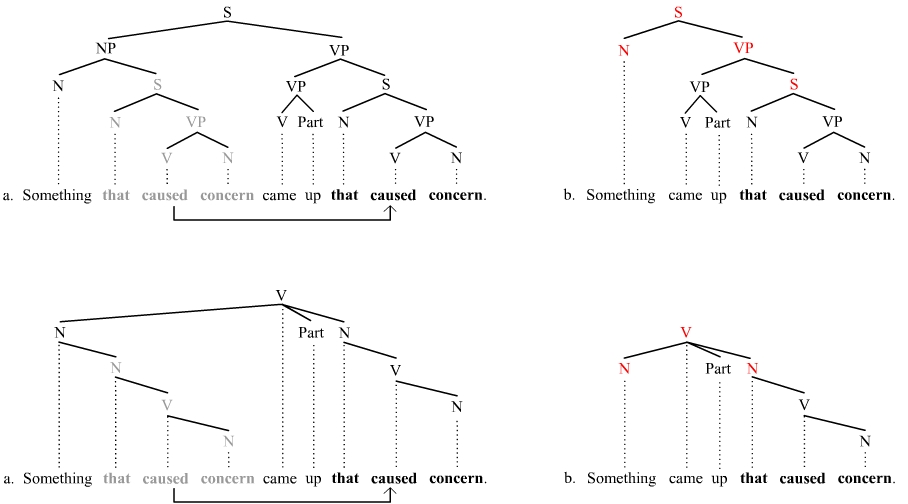

Theories of syntax vary in their analyses of extraposition. Derivational theories are likely to produce an analysis in terms of movement (or copying), and representational theories are likely to assume feature passing (instead of movement). The following trees illustrate these analyses. The movement-type analysis appears on the left in the a-trees, and the feature passing analysis on the right in the b-trees. The constituency-based trees appear again above the dependency-based trees.

On the movement analysis in the a-trees, the embedded clause is first generated in its canonical position.[5] To increase right-branching it then moves rightward to its surface position. On the feature passing analysis in the b-trees, no movement is involved. Instead, information about the extraposed constituent is passed along the path marked in red. This path extends from the extraposed constituent to what can be viewed as the governor of the extraposed constituent.[6] The words in red in the dependency tree qualify as a concrete unit of syntax; they form a catena.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ For accounts of extraposition, see for instance Guéron (1990), Baltin (1981, 1983), Guéron and May (1984), Stucky (1987), Wittenberg (1987), Culicover and Rochemont (1990), Huck and Na (1990).

- ^ The Right Roof Constraint is attributed to Ross (1967). See also Gross and Osborne (2009:83-85). Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43-90.

- ^ Rosenbaum (1967) may have been the first to look at it-extraposition.

- ^ See Francis (2010).

- ^ See Ross (1967) and Baltin (1981) for such rightward movement analyses.

- ^ For a dependency grammar analysis in terms of feature passing, see Osborne (2012).

References[edit]

- Baltin, M. 1981. Strict bounding. In C. L. Baker and J. McCarthy (eds.), The logical problem of language acquisition, 257-295. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Baltin, M. 1983. Extraposition: Bounding vs. Government-Binding. Linguistic Inquiry, 14, 1, 155-162.

- Culicover, P. and M. Rochemont 1990. Extraposition and the complement principle. Linguistic Inquiry 21, 1, 23-47.

- Francis, E. 2010. Grammatical weight and relative clause extraposition in English. Cognitive Linguistics 21, 1, 35-74.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43-90.

- Guéron, J. 1980. On the syntax and semantics of extraposition. Linguistic Inquiry 11, 637-678.

- Guéron, J. and R. May 1984. Extraposition and Logical Form. Linguistic Inquiry 15, 1-31.

- Huck, G. and Y. Na 1990. Extraposition and focus. Language 66, 51-77.

- Osborne, T. 2012. Edge features, catenae, and dependency-based Minimalism. Linguistic Analysis 34, 3-4, 321-366.

- Rosenbaum, P. 1967. The grammar of English predicate complement constructions. Cambridge, Massachusetts, M.I.T. Press.

- Ross, J. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Stucky, S. 1987. Configurational variation in English: A study of extraposition and related matters. In J. Huck and A. Ojeda (eds.), Syntax and Semantics 20, Discontinuous constituency. San Diego, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers.

- Wittenberg, K. 1987. Extraposition from NP as anaphora. In J. Huck and A. Ojeda (eds.), Syntax and Semantics, Volume 20: Discontinuous Constituency. San Diego, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers.