An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

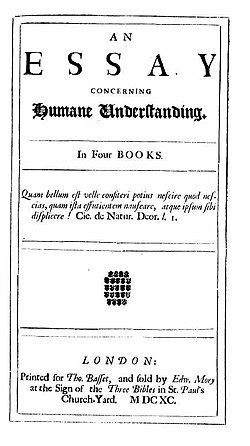

Title page of the first edition | |

| Author | John Locke |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Epistemology |

Publication date | 1689 (dated 1690) |

|

| Part of a series on |

| John Locke |

|---|

|

Works (listed chronologically) |

| People |

| Related topics |

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. He describes the mind at birth as a blank slate (tabula rasa, although he did not use those actual words) filled later through experience. The essay was one of the principal sources of empiricism in modern philosophy, and influenced many enlightenment philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley.

Book I of the Essay is Locke's attempt to refute the rationalist notion of innate ideas. Book II sets out Locke's theory of ideas, including his distinction between passively acquired simple ideas, such as "red," "sweet," "round," etc., and actively built complex ideas, such as numbers, causes and effects, abstract ideas, ideas of substances, identity, and diversity. Locke also distinguishes between the truly existing primary qualities of bodies, like shape, motion and the arrangement of minute particles, and the secondary qualities that are "powers to produce various sensations in us"[1] such as "red" and "sweet." These secondary qualities, Locke claims, are dependent on the primary qualities. He also offers a theory of personal identity, offering a largely psychological criterion. Book III is concerned with language, and Book IV with knowledge, including intuition, mathematics, moral philosophy, natural philosophy ("science"), faith, and opinion.

Contents

Book I[edit]

The main thesis is that there are "No Innate Principles", by this reasoning:

If we will attentively consider new born children, we shall have little reason to think that they bring many ideas into the world with them

and that "by degrees afterward, ideas come into their minds."[2] Book I of the Essay is devoted to an attack on nativism or the doctrine of innate ideas; Locke indeed sought to rebut a prevalent view, of innate ideas, that was vehemently held by philosophers of his time. Locke allowed that some ideas are in the mind from an early age, but argued that such ideas are furnished by the senses starting in the womb: for instance, differences between colours or tastes. If we have a universal understanding of a concept like sweetness, it is not because this is an innate idea, but because we are all exposed to sweet tastes at an early age.[3]

One of Locke's fundamental arguments against innate ideas is the very fact that there is no truth to which all people attest. He took the time to argue against a number of propositions that rationalists offer as universally accepted truth, for instance the principle of identity, pointing out that at the very least children and idiots are often unaware of these propositions.[4] In anticipating a counter-argument, namely the use of reason to comprehend already existent innate ideas, Locke states, "by this means there will be no Difference between the Maxims of the Mathematicians, and Theorems they deduce from them: All must equally allow’d innate, they being all Discoveries made by the use of reason."[5]

Book II[edit]

Whereas Book I is intended to reject the doctrine of innate ideas proposed by Descartes and the rationalists, Book II explains that every idea is derived from experience either by sensation – direct sensory information – or reflection – "the perception of the operations of our own mind within us, as it is employed about the ideas it has got".

Furthermore, Book II is also a systematic argument for the existence of an intelligent being: "Thus, from the consideration of ourselves, and what we infallibly find in our own constitutions, our reason leads us to the knowledge of this certain and evident truth, that there is an eternal, most powerful, and most knowing being; which whether any one will please to call God, it matters not!"

Book III[edit]

Book 3 focuses on words. Locke connects words to the ideas they signify, claiming that man is unique in being able to frame sounds into distinct words and to signify ideas by those words, and then that these words are built into language.

Chapter ten in this book focuses on "Abuse of Words." Here, Locke criticizes metaphysicians for making up new words that have no clear meaning. He also criticizes the use of words which are not linked to clear ideas, and to those who change the criteria or meaning underlying a term.

Thus he uses a discussion of language to demonstrate sloppy thinking. Locke followed the Port-Royal Logique (1662)[6] in numbering among the abuses of language those that he calls "affected obscurity" in chapter 10. Locke complains that such obscurity is caused by, for example, philosophers who, to confuse their readers, invoke old terms and give them unexpected meanings or who construct new terms without clearly defining their intent. Writers may also invent such obfuscation to make themselves appear more educated or their ideas more complicated and nuanced or erudite than they actually are.

Book IV[edit]

This book focuses on knowledge in general – that it can be thought of as the sum of ideas and perceptions. Locke discusses the limit of human knowledge, and whether knowledge can be said to be accurate or truthful.

Thus there is a distinction between what an individual might claim to "know", as part of a system of knowledge, and whether or not that claimed knowledge is actual. Locke writes at the beginning of the fourth chapter, Of the Reality of Knowledge): "I doubt not my Reader by this Time may be apt to think that I have been all this while only building a Castle in the Air; and be ready to say to me, To what purpose all of this stir? Knowledge, say you, is only the Perception of the Agreement or Disagreement of our own Ideas: but who knows what those Ideas may be? ... But of what use is all this fine Knowledge of Man's own Imaginations, to a Man that enquires after the reality of things? It matters now that Mens Fancies are, 'tis the Knowledge of Things that is only to be priz'd; 'tis this alone gives a Value to our Reasonings, and Preference to one Man's Knowledge over another's, that is of Things as they really are, and of Dreams and Fancies."

In the last chapter of the book, Locke introduces the major classification of sciences into physics, semiotics, and ethics.

Reaction, response, and influence[edit]

Many of Locke's views were sharply criticized by rationalists and empiricists alike. In 1704 the rationalist Gottfried Leibniz wrote a response to Locke's work in the form of a chapter-by-chapter rebuttal, the Nouveaux essais sur l'entendement humain ("New Essays on Human Understanding"). Leibniz was critical of a number of Locke's views in the Essay, including his rejection of innate ideas, his skepticism about species classification, and the possibility that matter might think, among other things. Leibniz thought that Locke's commitment to ideas of reflection in the Essay ultimately made him incapable of escaping the nativist position or being consistent in his empiricist doctrines of the mind's passivity. The empiricist George Berkeley was equally critical of Locke's views in the Essay. Berkeley's most notable criticisms of Locke were first published in A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. Berkeley held that Locke's conception of abstract ideas was incoherent and led to severe contradictions. He also argued that Locke's conception of material substance was unintelligible, a view which he also later advanced in the Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous. At the same time, Locke's work provided crucial groundwork for future empiricists such as David Hume. John Wynne published An Abridgment of Mr. Locke's Essay concerning the Human Understanding, with Locke's approval, in 1696. Louisa Capper wrote An Abridgment of Locke's Essay concerning the Human Understanding, published in 1811.

Editions[edit]

- Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. 1st ed. 1 vols. London: Thomas Bassett, 1690.

- Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by Alexander Campbell Fraser. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894.

- Locke, John. Works, Vol 1. London: Taylor, 1722.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Essay, II, viii, 10

- ^ Essay, I, iii, 2.

- ^ Essay, I, ii, 15.

- ^ Essay, I, iv, 3.

- ^ Locke, John (1753). An Essay concerning Human Understanding ... The fourteenth edition. [With a portrait.]. S. Birt.

- ^ Arnauld, Antoine; Nicole, Pierre (1662). La logique ou l'Art de penser. Paris: Jean Guignart, Charles Savreux, & Jean de Lavnay.. See part 1, chapter 13, Observations importantes touchant la définition des noms.

Bibliography[edit]

- Clapp, James Gordon. "John Locke." Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan, 1967.

- Uzgalis, William. "John Locke." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved on 22 July 2007.

- Ayers, Michael. Locke: Epistemology and Ontology. 2 vols. London: Routledge, 1991.

- Bennett, Jonathan. Locke, Berkeley, Hume: Central Themes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Bizzell, Patricia, and Bruce Herzberg, eds. The Rhetorical Tradition. 2nd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2001.

- Chappell, Vere, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Fox, Christopher. Locke and the Scriblerians. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- Jolley, Nicholas. Locke: His Philosophical Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Lowe, E.J. Locke on Human Understanding. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Yolton, John. John Locke and the Way of Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956.

- Yolton, John. John Locke and the Compass of Human Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding |