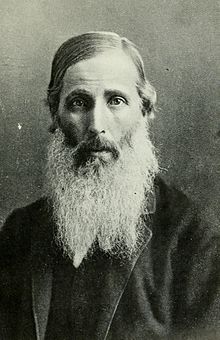

Henry Sidgwick

Professor Henry Sidgwick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 31 May 1838 |

| Died | 28 August 1900 (aged 62) |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Utilitarianism |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge |

Main interests | Ethics, politics |

Notable ideas | Ethical hedonism, paradox of hedonism |

Influences

| |

Henry Sidgwick (/ˈsɪdʒwɪk/; 31 May 1838 – 28 August 1900) was an English utilitarian philosopher and economist.[1] He was the Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1883 until his death, and is best known in philosophy for his utilitarian treatise The Methods of Ethics.[2] He was one of the founders and first president of the Society for Psychical Research and a member of the Metaphysical Society and promoted the higher education of women. His work in economics has also had a lasting influence.

He also founded Newnham College in 1875, a women-only constituent college of the University of Cambridge. It was the second Cambridge college to admit women after Girton College. The co-founder of the college was Millicent Garrett Fawcett.

He joined the Cambridge Apostles intellectual secret society in 1856.

Contents

Biography[edit]

He was born at Skipton in Yorkshire, where his father, the Reverend W. Sidgwick (d. 1841), was headmaster of the local grammar school, Ermysted's Grammar School. His mother was Mary Sidgwick, née Crofts (1807–1879).

Henry himself was educated at Rugby (where his cousin, subsequently his brother-in-law, Edward White Benson, later Archbishop of Canterbury, was a master), and at Trinity College, Cambridge. While at Trinity, Sidgwick became a member of the Cambridge Apostles. In 1859, he was senior classic, 33rd wrangler, chancellor's medallist and Craven scholar. In the same year, he was elected to a fellowship at Trinity and soon afterwards he became a lecturer in classics there, a post he held for ten years.[3] The Sidgwick Site, home to several of the university's arts and humanities faculties, is named after him.

In 1869, he exchanged his lectureship in classics for one in moral philosophy, a subject to which he had been turning his attention. In the same year, deciding that he could no longer in good conscience declare himself a member of the Church of England, he resigned his fellowship. He retained his lectureship and in 1881 he was elected an honorary fellow. In 1874 he published The Methods of Ethics (6th ed. 1901, containing emendations written just before his death), by common consent a major work, which made his reputation outside the university. John Rawls called it the "first truly academic work in moral theory, modern in both method and spirit".[4]

In 1875, he was appointed praelector on moral and political philosophy at Trinity, and in 1883 he was elected Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy. In 1885, the religious test having been removed, his college once more elected him to a fellowship on the foundation.

Besides his lecturing and literary labours, Sidgwick took an active part in the business of the university and in many forms of social and philanthropic work. He was a member of the General Board of Studies from its foundation in 1882 to 1899; he was also a member of the Council of the Senate of the Indian Civil Service Board and the Local Examinations and Lectures Syndicate and chairman of the Special Board for Moral Science.[citation needed]

He married Eleanor Mildred Balfour, who was a member of the Ladies Dining Society in Cambridge, with 11 other members, and was sister to Arthur Balfour.

A 2004 biography of Sidgwick by Bart Schultz sought to establish that Sidgwick was a lifelong homosexual, but it is unknown whether he ever consummated his inclinations. According to the biographer, Sidgwick struggled internally throughout his life with issues of hypocrisy and openness in connection with his own forbidden desires.[5][6]

He was one of the founders and first president of the Society for Psychical Research, and was a member of the Metaphysical Society.

He also took in promoting the higher education of women. He helped to start the higher local examinations for women, and the lectures held at Cambridge in preparation for these. It was at his suggestion and with his help that Anne Clough opened a house of residence for students, which developed into Newnham College, Cambridge. When, in 1880, the North Hall was added, Sidgwick, who, in 1876, had married Eleanor Mildred Balfour (sister of A. J. Balfour), lived there for two years. His wife became principal of the college after Clough's death in 1892, and they lived there for the rest of his life. During this whole period, Sidgwick took the deepest interest in the welfare of the college. In politics, he was a liberal, and became a Liberal Unionist (a party that later effectively merged with the Conservative party) in 1886.

Early in 1900 he was forced by ill-health to resign his professorship, and died a few months later.[citation needed] Sidgwick, who died an agnostic,[7] is buried in Terling All Saints Churchyard, Terling, Essex, with his wife.

Exposure of the fraud of Palladino[edit]

In July 1895, the medium Eusapia Palladino was invited to England to Frederic William Henry Myers's house in Cambridge for a series of investigations into her mediumship. According to reports by the investigators, Myers and Oliver Lodge, all the phenomena observed in the Cambridge sittings were the result of trickery. Her fraud was so clever, according to Myers, that it "must have needed long practice to bring it to its present level of skill."[8]

In the Cambridge sittings, the results proved disastrous for her mediumship. During the séances, Palladino was caught cheating to free herself from the physical controls of the experiments.[9] Palladino was found liberating her hands by placing the hand of the controller on her left on top of the hand of the controller on her right. Instead of maintaining any contact with her, the observers on either side were found to be holding each other's hands, which made it possible for her to perform tricks.[10] Richard Hodgson had observed Palladino free a hand to move objects and use her feet to kick pieces of furniture in the room. Because of the discovery of fraud, the British SPR investigators such as Sidgwick and Frank Podmore considered Palladino's mediumship to be permanently discredited and because of her fraud she was banned from any further experiments with the SPR in Britain.[10]

In the British Medical Journal on 9 November 1895 an article was published titled Exit Eusapia!. The article questioned the scientific legitimacy of the SPR for investigating Palladino, a medium who had a reputation of being a fraud and imposture.[11] Part of the article read: "It would be comic if it were not deplorable to picture this sorry Egeria surrounded by men like Professor Sidgwick, Professor Lodge, Mr. F. H. Myers, Dr. Schiaparelli, and Professor Richet, solemnly receiving her pinches and kicks, her finger skiddings, her sleight of hand with various articles of furniture as phenomena calling for serious study."[11] This caused Sidgwick to respond in a published letter to the British Medical Journal, 16 November 1895. According to Sidgwick SPR members had exposed the fraud of Palladino at the Cambridge sittings, Sidgwick wrote "Throughout this period we have continually combated and exposed the frauds of professional mediums, and have never yet published in our Proceedings, any report in favour of the performances of any of them."[12] The response from the Journal questioned why the SPR wastes time investigating phenomena that are the "result of jugglery and imposture" and not urgently concerning the welfare of mankind.[12]

In 1898, Myers was invited to a series of séances in Paris with Charles Richet. In contrast to the previous séances in which he had observed fraud, he claimed to have observed convincing phenomena.[13] Sidgwick reminded Myers of Palladino's trickery in the previous investigations as "overwhelming" but Myers did not change his position. That enraged Richard Hodgson, then editor of SPR publications, to ban Myers from publishing anything on his recent sittings with Palladino in the SPR journal. Hodgson was convinced Palladino was a fraud and supported Sidgwick in the "attempt to put that vulgar cheat Eusapia beyond the pale".[13] It was only in the 1908 sittings in Naples that the SPR reopened the Palladino file.[14]

Opinions[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Utilitarianism |

|---|

|

Types of utilitarianism |

|

Related topics |

| Politics portal |

Sidgwick was a famous teacher. He treated his pupils as fellow students. He was deeply interested in psychical phenomena, but his energies were primarily devoted to the study of religion and philosophy.[citation needed]

Brought up in the Church of England, he drifted away from orthodox Christianity, and as early as 1862 he described himself as a theist, independent from established religion.[15] For the rest of his life, although he regarded Christianity as "indispensable and irreplaceable – looking at it from a sociological point of view," he found himself unable to return to it as a religion.

In political economy he was a utilitarian on the lines of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham.

His work was characterised by its careful investigation of first principles, as in his distinction of positive and normative reasoning, and by critical analysis, not always constructive. His influence was such that for example Alfred Marshall, founder of the Cambridge School of economics, would describe him as his "spiritual mother and father."[16] In philosophy, he devoted himself to ethics, and especially to the examination of the ultimate intuitive principles of conduct and commonsense morality, which he probes with great depth and subtlety in his major work, The Methods of Ethics (1874).

He adopted a position that may be described as ethical hedonism, according to which the criterion of goodness in any given action is that it produces the greatest possible amount of personal pleasure. The hedonism, however, is not confined to the self (egoistic), but involves a due regard to the pleasure of others, and is, therefore, distinguished further as universalistic (a version of utilitarianism).

As Sidgwick sees it, one of the central issues of ethics is whether self-interest and duty always coincide. To a great extent they do, Sidgwick argues, but it cannot be proved that they never conflict, except by appeal to a divine system of punishments and rewards that Sidgwick believes is out of place in a work of philosophical ethics. The upshot is that there is a "dualism of practical reason."

Bibliography[edit]

- The Ethics of Conformity and Subscription. 1870.

- The Methods of Ethics. London, 1874, 7th edition 1907.

- The Theory of Evolution in its application to Practice, in Mind, Volume I, Number 1 January 1876, 52–67,

- Principles of Political Economy. London, 1883, 3rd edition 1901.

- The Scope and Method of Economic Science. 1885.

- Outlines of the History of Ethics for English Readers. 1886 5th edition 1902 (enlarged from his article ethics in the Encyclopædia Britannica).

- The Elements of Politics. London, 1891, 4th edition 1919.

- "The Philosophy of Common Sense", in Mind, New Series, Volume IV, Number 14, April 1895, 145–158.

- Economic science and economics, Palgrave's Dictionary of Political Economy, 1896, v. 1, reprinted in The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 1987, v. 2, 58–59.

- Practical Ethics. London, 1898, 2nd edition 1909.

- Philosophy; its Scope and Relations. London, 1902.

- Lectures on the Ethics of T. H. Green, Mr Herbert Spencer and J. Martineau. 1902.

- The Development of European Polity. 1903, 3rd edition 1920

- Miscellaneous Essays and Addresses. 1904.

- Lectures on the Philosophy of Kant and other philosophical lectures and essays. 1905.

- Sidgwick's writings available online

See also[edit]

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ Bryce, James (1903). "Henry Sidgwick". Studies in Contemporary Biography. New York: Macmillan. pp. 327–342.

- ^ Schultz 2004

- ^ "Sidgwick, Henry (SGWK855H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Rawls, J. 1980. 'Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory'. Journal of Philosophy 77 (1980).

- ^ Schultz, B. (2004). Henry Sidgwick, eye of the universe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Schultz's book reviewed: Martha Nussbaum, "The Epistemology of the Closet." The Nation, 6 June 2005.

- ^ Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke, Damian Riehl Leader (1988). "1: Prologue". A History of the University of Cambridge: 1870–1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521343503.

In 1869 Henry Sidgwick, who had become a devout agnostic, made protest against the survival of religious tests in Cambridge by resigning his Trinity fellowship.

- ^ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?: The Evidence Given by Sir A.C. Doyle and Others. London, Watts & Co. p. 14

- ^ Walter Mann. (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co. pp. 115–130

- ^ a b M. Brady Brower. (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0252077517

- ^ a b The British Medical Journal. (9 November 1895). Exit Eusapia!. Volume. 2, No. 1819. p. 1182.

- ^ a b The British Medical Journal. (16 November 1895). Exit Eusapia. Volume 2, No. 1820. pp. 1263–1264.

- ^ a b Janet Oppenheim. (1985). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0521265058

- ^ Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ^ "Losing My Religion":Sidgwick, Theism, and the Struggle for Utilitarian Ethics in Economic Analysis by Steven G. Medema: http://hope.dukejournals.org/cgi/reprint/40/5/189.pdf

- ^ Phyllis Deane, "Sidgwick, Henry," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 1987, v. 4, pp. 328–29.

Further reading[edit]

- Schultz, Bart. Henry Sidgwick: Eye of the Universe. An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Schultz, Bart. "Henry Sidgwick". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 5 October 2004.

- Blum, Deborah. Ghost Hunters. Arrow Books, 2007.

- Dawes, Ann. "Henry Sidgwick". Biograph, 2007

- (in French) Geninet, Hortense. POLITIQUES COMPAREES, Henry Sidgwick et la politique moderne dans les Éléments Politiques, Edited by Hortense Geninet, France, September 2009. ISBN 978-2-7466-1043-9

- Nakano-Okuno, Mariko. Sidgwick and Contemporary Utilitarianism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. ISBN 978-0-230-32178-6

- Phillips, David. Sidgwickian Ethics. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Schneewind, Jerome. Sidgwick's Ethics and Victorian Moral Philosophy. Clarendon Press, 1977.

- Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, Peter Singer. The Point of View of the Universe: Sidgwick and Contemporary Ethics. Oxford University Press, 2014.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry Sidgwick |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Sidgwick |

- Henry Sidgwick Website

- Official website of the 2nd International congress : Henry Sidgwick Ethics, Psychics, Politics. University of Catania – Italy

- Henry Sidgwick. Comprehensive list of online writings by and about Sidgwick.

- Contains Sidgwick's "Methods of Ethics", modified for easier reading

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 1838 births

- 1900 deaths

- 19th-century British male writers

- 19th-century British philosophers

- 19th-century English philosophers

- 19th-century philosophers

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- British agnostics

- British economists

- British ethicists

- British feminists

- British male non-fiction writers

- British political philosophers

- British political theorists

- British philosophers

- Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club

- Consequentialists

- English agnostics

- English economists

- English feminists

- English male non-fiction writers

- English political philosophers

- English political theorists

- English philosophers

- Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Feminist philosophers

- Individualist feminists

- Male feminists

- Moral philosophers

- Parapsychologists

- People educated at Rugby School

- People from Skipton

- Philosophers of ethics and morality

- Presidents of The Cambridge Union

- Utilitarians