Muhammad Iqbal

Muhammad Iqbal محمد اِقبال | |

|---|---|

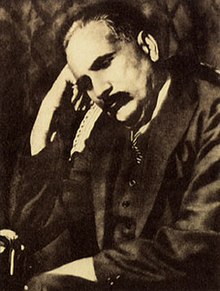

Allama Muhammad Iqbal | |

| Born | Muhammad Iqbal 9 November 1877 |

| Died | 21 April 1938 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | British India |

| Education | Scotch Mission College (F.A.) Government College (B.A., M.A.) University of Cambridge (B.A.) University of Munich (Ph.D.) |

Notable work | Bang-e-Dara, The Secrets of the Self, The Secrets of Selflessness, Message from the East, Persian Psalms, Javid Nama, "Sare Jahan se Accha" (more works) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Islamic philosophy |

| School | Islamic law |

Main interests | Islam, Urdu poetry, Persian poetry, law |

Notable ideas | Allahabad Address |

Sir Muhammad Iqbal (/ˈɪkbɑːl/; Urdu: محمد اِقبال; 9 November 1877 – 21 April 1938), widely known as Allama Iqbal, was a poet, philosopher and politician, as well as an academic, barrister and scholar[1][2] in British India who is widely regarded as having inspired the Pakistan Movement. He is called the "Spiritual Father of Pakistan."[3] He is considered one of the most important figures in Urdu literature,[4] with literary work in both Urdu and Persian.[2][4]

Iqbal is admired as a prominent poet by Indians, Pakistanis, Iranians and other international scholars of literature.[5][6][7] Though Iqbal is best known as an eminent poet, he is also a highly acclaimed "Muslim philosophical thinker of modern times".[2][7] His first poetry book, The Secrets of the Self, appeared in the Persian language in 1915, and other books of poetry include The Secrets of Selflessness, Message from the East and Persian Psalms. Amongst these, his best known Urdu works are The Call of the Marching Bell, Gabriel's Wing, The Rod of Moses and a part of Gift from Hijaz.[8] Along with his Urdu and Persian poetry, his Urdu and English lectures and letters have been very influential in cultural, social, religious and political disputes.[8]

In the 1923 New Years Honours he was made a Knight Bachelor by King George V,[9][10] While studying law and philosophy in England, Iqbal became a member of the London branch of the All-India Muslim League.[7][8] Later, during the League's December 1930 session, he delivered his most famous presidential speech known as the Allahabad Address in which he pushed for the creation of a Muslim state in north-west India.[7][8]

In much of South Asia and the Urdu-speaking world, Iqbal is regarded as the Shair-e-Mashriq (Urdu: شاعر مشرق, "Poet of the East").[11][12][13] He is also called Mufakkir-e-Pakistan (Urdu: مفکر پاکستان, "The Thinker of Pakistan"), Musawar-e-Pakistan (Urdu: مصور پاکستان, "Artist of Pakistan") and Hakeem-ul-Ummat (Urdu: حکیم الامت, "The Sage of the Ummah"). The Pakistan government officially named him "National Poet of Pakistan".[7] His birthday Yōm-e Welādat-e Muḥammad Iqbāl (Urdu: یوم ولادت محمد اقبال), or Iqbal Day, is a public holiday in Pakistan.[14]

Iqbal's house is still located in Sialkot and is recognized as Iqbal's Manzil and is open for visitors. His other house where he lived most of his life and died is in Lahore, named as Javed Manzil. The museum is located on Allama Iqbal Road near Lahore Railway Station, Punjab, Pakistan.[15] It was protected under the Punjab Antiquities Act of 1975, and declared a Pakistani national monument in 1977.[15][better source needed]

Contents

Personal life[edit]

Background[edit]

Iqbal was born on 9 November 1877 in an ethnic Kashmiri family in Sialkot within the Punjab Province of British India (now in Pakistan).[16] His grandfather's name was Sheikh Mohammad Rafique. His ancestors were Kashmiri Brahmins of the Sapru clan and had converted to Islam in the time of Bud Shah.[17][not in citation given] The first ancestor to convert to Islam has been identified as Haji Lal, a Sufi mystic.[18] In the 19th century, when the Sikh Empire was conquering Kashmir, his grandfather's family migrated to Punjab. Iqbal often mentioned and commemorated his Kashmiri lineage in his writings.[19][12]

Iqbal's father, Sheikh Noor Muhammad (died 1930), was a tailor, not formally educated, but a religious man.[20][21] Iqbal's mother Imam Bibi, a Punjabi Muslim from Sialkot, was described as a polite and humble woman who helped the poor and her neighbours with their problems. She died on 9 November 1914 in Sialkot.[22][23] Iqbal loved his mother, and on her death he expressed his feelings of pathos in a poetic form elegy.[20]

Who would wait for me anxiously in my native place?

Who would display restlessness if my letter fails to arrive?

I will visit thy grave with this complaint:

Who will now think of me in midnight prayers?

All thy life thy love served me with devotion—

When I became fit to serve thee, thou hast departed.[20]

Early education[edit]

Iqbal was four years old when he was admitted to the mosque to learn the Qur'an. He learned the Arabic language from his teacher, Syed Mir Hassan, the head of the madrasa and professor of Arabic at Scotch Mission College in Sialkot, where he matriculated in 1893.[24] He received Intermediate with the Faculty of Arts diploma in 1895.[12][23][25] The same year he enrolled at Government College University, where he obtained his Bachelor of Arts in philosophy, English literature and Arabic in 1897, and won the Khan Bahadurddin F.S. Jalaluddin medal as he performed well in Arabic.[23] In 1899, he received his Master of Arts degree from the same college and had the first place[clarification needed] in University of the Punjab.[12][23][25]

Marriages[edit]

Iqbal married thrice, under different times of need and circumstances.[26] His first marriage was held in 1895, when he was 18 years old. His bride Karim Bibi was the daughter of a physician, Khan Bahadur Ata Muhammad Khan. Her sister was the mother of director and music composer Khwaja Khurshid Anwar.[27][28] The marriage was arranged by their families, and the couple had two children; a daughter Miraj Begum (1895–1915) and a son, Aftab Iqbal (1899–1979) who became a barrister.[26][29] Another son is said to have died after birth in 1901.[30] Iqbal's second marriage was with Mukhtar Begum and it was held in December 1914, shortly after the death of Iqbal's mother the previous November.[11][23] They had a son, but both the mother and son died shortly after birth in 1924.[26] Later, Iqbal married Sardar Begum and they became the parents of a son, Javed Iqbal (1924–2015), who was to become a judge, and a daughter Muneera Bano (b. 1930).[26][30] One of Muneera's sons is the philanthropist-cum-socialite Yousuf Salahuddin.[30]

Higher education in Europe[edit]

Iqbal was influenced by the teachings of Sir Thomas Arnold, his philosophy teacher at Government College Lahore. Arnold's teachings convinced Iqbal to pursue higher education in the West, and in 1905, he travelled to England for that purpose. Iqbal qualified for a scholarship from Trinity College, University of Cambridge and obtained Bachelor of Arts in 1906, and in the same year he was called to the bar as a barrister from Lincoln's Inn. In 1907, Iqbal moved to Germany to pursue his doctoral studies, and earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1908. Working under the guidance of Friedrich Hommel, Iqbal's doctoral thesis, entitled The Development of Metaphysics in Persia, was published.[12][31][32][33]

During Iqbal's stay in Heidelberg in 1907 his German professor Emma Wegenast taught him about Goethe's Faust, Heine and Nietzsche.[34] During his study in Europe, Iqbal began to write poetry in Persian. He preferred to write in this language because doing so made easier to express his thoughts. He would write continuously in Persian throughout his life.[12]

Iqbal had a great interest in Islamic studies, especially Sufi beliefs. This is evident from his poetry, in which apart from independence ideologies, he also explores concepts of submission to Allah and following the path of Prophet Muhammad.

Academic career[edit]

Iqbal, after completing his Master of Arts degree in 1899, began his career as a reader of Arabic at Oriental College and shortly afterwards was selected as a junior professor of philosophy at Government College Lahore, where he had also been a student in the past. He worked there until he left for England in 1905. In 1908, he returned from England and joined the same college again as a professor of philosophy and English literature.[35] In the same period Iqbal began practising law at Chief Court Lahore, but he soon quit law practice and devoted himself in literary works, becoming an active member of Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam.[23] In 1919, he became the general secretary of the same organisation. Iqbal's thoughts in his work primarily focus on the spiritual direction and development of human society, centred around experiences from his travels and stays in Western Europe and the Middle East. He was profoundly influenced by Western philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson and Goethe.[20][34]

The poetry and philosophy of Mawlana Rumi bore the deepest influence on Iqbal's mind. Deeply grounded in religion since childhood, Iqbal began concentrating intensely on the study of Islam, the culture and history of Islamic civilisation and its political future, while embracing Rumi as "his guide".[20] Iqbal would feature Rumi in the role of guide in many of his poems.[clarification needed] Iqbal's works focus on reminding his readers of the past glories of Islamic civilisation, and delivering the message of a pure, spiritual focus on Islam as a source for socio-political liberation and greatness. Iqbal denounced political divisions within and amongst Muslim nations, and frequently alluded to and spoke in terms of the global Muslim community or the Ummah.[8][20]

Iqbal's poetry was translated into many European languages in the early part of the 20th century, when his work was famous.[7] Iqbal's Asrar-i-Khudi and Javed Nama were translated into English by R. A. Nicholson and A. J. Arberry, respectively.[7][13]

Career as a Lawyer[edit]

Iqbal was not only a prolific writer but was also a known Advocate. He used to appear before the Lahore High Court in both civil and criminal matters. There are more than 100 reported judgments to his name.[citation needed]

Final years and death[edit]

In 1933, after returning from a trip to Spain and Afghanistan, Iqbal suffered from a mysterious throat illness.[36] He spent his final years helping Chaudhry Niaz Ali Khan to establish the Dar ul Islam Trust Institute at Jamalpur estate near Pathankot,[37][38] where there were plans to subsidise studies in classical Islam and contemporary social science. He also advocated for an independent Muslim state.

Iqbal ceased practising law in 1934 and was granted a pension by the Nawab of Bhopal. In his final years, he frequently visited the Dargah of famous Sufi Ali Hujwiri in Lahore for spiritual guidance. After suffering for months from his illness, Iqbal died in Lahore on 21 April 1938.[8][12] His tomb is located in Hazuri Bagh, the enclosed garden between the entrance of the Badshahi Mosque and the Lahore Fort, and official guards are provided by the Government of Pakistan.

Iqbal is commemorated widely in Pakistan, where he is regarded as the ideological founder of the state. His Tarana-e-Hind is a song that is widely used in India as a patriotic song speaking of communal harmony. His birthday is annually commemorated in Pakistan as Iqbal Day. Iqbal is the namesake of many public institutions, including the Allama Iqbal Campus Punjab University in Lahore, the Allama Iqbal Medical College in Lahore, Iqbal Stadium in Faisalabad, Allama Iqbal Open University in Pakistan, Iqbal Memorial Institute in Srinagar, Allama Iqbal Library in University of Kashmir, the Allama Iqbal International Airport in Lahore, Iqbal Hostel in Government College University, Lahore, the Allama Iqbal hall in Nishtar Medical College in Multan, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town in Karachi, Allama Iqbal Town in Lahore, and Allama Iqbal Hall at Aligarh Muslim University.

The government and public organisations have sponsored the establishment of educational institutions, colleges and schools dedicated to Iqbal, and have established the Iqbal Academy Pakistan to research, teach and preserve his works, literature and philosophy. Allama Iqbal Stamps Society was established for the promotion of Iqbaliyat in philately and in other hobbies. His son Javid Iqbal has served as a justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. Javaid Manzil was Iqbal's last residence.[39]

Efforts and influences[edit]

Political[edit]

As Iqbal was interested in the national affairs since his youth and he had got considerable recognition after his return in 1908 from England by Punjabi elite, he was closely associated with Mian Muhammad Shafi. So when the All-India Muslim League was expanded to the provincial level and Mian Mohammad Shafi received a major role to play in the structural organization of Provincial League, Iqbal was made one of the first three joint secretaries of the Punjab Muslim League with Shaikh Abdul Aziz and Maulvi Mahbub Alam.[40] While dividing his time between law practice and poetry, Iqbal had remained active in the Muslim League. He did not support Indian involvement in World War I and remained in close touch with Muslim political leaders such as Mohammad Ali Jouhar and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He was a critic of the mainstream Indian National Congress, which he regarded as dominated by Hindus, and was disappointed with the League when during the 1920s, it was absorbed in factional divides between the pro-British group led by Sir Muhammad Shafi and the centrist group led by Jinnah.[41][unreliable source?]

(L to R): M. Iqbal (third), Syed Zafarul Hasan (sixth) at Aligarh Muslim University

In November 1926, with the encouragement of friends and supporters, Iqbal contested the election for a seat in the Punjab Legislative Assembly from the Muslim district of Lahore, and defeated his opponent by a margin of 3,177 votes.[8] He supported the constitutional proposals presented by Jinnah with the aim of guaranteeing Muslim political rights and influence in a coalition with the Congress, and worked with the Aga Khan and other Muslim leaders to mend the factional divisions and achieve unity in the Muslim League.[41][unreliable source?] While in Lahore he was a friend of Abdul Sattar Ranjoor.[42]

Iqbal, Jinnah and concept of Pakistan[edit]

Ideologically separated from Congress Muslim leaders, Iqbal had also been disillusioned with the politicians of the Muslim League, owing to the factional conflict that plagued the League in the 1920s. Discontent with factional leaders like Muhammad Shafi and Fazl-ur-Rahman, Iqbal came to believe that only Jinnah was a political leader capable of preserving unity and fulfilling the League's objectives of Muslim political empowerment. Building a strong, personal correspondence with Jinnah, Iqbal was an influential force in convincing Jinnah to end his self-imposed exile in London, return to India and take charge of the League. Iqbal firmly believed that Jinnah was the only leader capable of drawing Indian Muslims to the League and maintaining party unity before the British and the Congress:

I know you are a busy man but I do hope you won't mind my writing to you often, as you are the only Muslim in India today to whom the community has right to look up for safe guidance through the storm which is coming to North-West India and, perhaps, to the whole of India.[43]

While Iqbal espoused the idea of Muslim-majority provinces in 1930, Jinnah would continue to hold talks with the Congress through the decade and only officially embraced the goal of Pakistan in 1940. Some historians postulate that Jinnah always remained hopeful for an agreement with the Congress and never fully desired the partition of India.[44] Iqbal's close correspondence with Jinnah is speculated by some historians as having been responsible for Jinnah's embrace of the idea of Pakistan. Iqbal elucidated to Jinnah his vision of a separate Muslim state in a letter sent on 21 June 1937:

A separate federation of Muslim Provinces, reformed on the lines I have suggested above, is the only course by which we can secure a peaceful India and save Muslims from the domination of Non-Muslims. Why should not the Muslims of North-West India and Bengal be considered as nations entitled to self-determination just as other nations in India and outside India are.[8]

Iqbal, serving as president of the Punjab Muslim League, criticised Jinnah's political actions, including a political agreement with Punjabi leader Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan, whom Iqbal saw as a representative of feudal classes and not committed to Islam as the core political philosophy. Nevertheless, Iqbal worked constantly to encourage Muslim leaders and masses to support Jinnah and the League. Speaking about the political future of Muslims in India, Iqbal said:

There is only one way out. Muslims should strengthen Jinnah's hands. They should join the Muslim League. Indian question, as is now being solved, can be countered by our united front against both the Hindus and the English. Without it, our demands are not going to be accepted. People say our demands smack of communalism. This is sheer propaganda. These demands relate to the defense of our national existence.... The united front can be formed under the leadership of the Muslim League. And the Muslim League can succeed only on account of Jinnah. Now none but Jinnah is capable of leading the Muslims.[43]

Revival of Islamic polity[edit]

Iqbal's six English lectures were published in Lahore in 1930, and then by the Oxford University Press in 1934 in a book titled The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. The lectures had been delivered at Madras, Hyderabad and Aligarh.[8] These lectures dwell on the role of Islam as a religion as well as a political and legal philosophy in the modern age.[8] In these lectures Iqbal firmly rejects the political attitudes and conduct of Muslim politicians, whom he saw as morally misguided, attached to power and without any standing with the Muslim masses.

Iqbal expressed fears that not only would secularism weaken the spiritual foundations of Islam and Muslim society, but that India's Hindu-majority population would crowd out Muslim heritage, culture and political influence. In his travels to Egypt, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey, he promoted ideas of greater Islamic political co-operation and unity, calling for the shedding of nationalist differences.[20] He also speculated on different political arrangements to guarantee Muslim political power; in a dialogue with Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Iqbal expressed his desire to see Indian provinces as autonomous units under the direct control of the British government and with no central Indian government. He envisaged autonomous Muslim provinces in India. Under a single Indian union he feared for Muslims, who would suffer in many respects especially with regard to their existentially separate entity as Muslims.[8]

Iqbal was elected president of the Muslim League in 1930 at its session in Allahabad in the United Provinces, as well as for the session in Lahore in 1932. In his presidential address on 29 December 1930 he outlined a vision of an independent state for Muslim-majority provinces in north-western India:[8]

I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated Northwest Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of Northwest India.[8]

In his speech, Iqbal emphasised that unlike Christianity, Islam came with "legal concepts" with "civic significance," with its "religious ideals" considered as inseparable from social order: "therefore, the construction of a policy on national lines, if it means a displacement of the Islamic principle of solidarity, is simply unthinkable to a Muslim."[45] Iqbal thus stressed not only the need for the political unity of Muslim communities but the undesirability of blending the Muslim population into a wider society not based on Islamic principles.

He thus became the first politician to articulate what would become known as the Two-nation theory—that Muslims are a distinct nation and thus deserve political independence from other regions and communities of India. Even as he rejected secularism and nationalism he would not elucidate or specify if his ideal Islamic state would construe a theocracy, and criticized the "intellectual attitudes" of Islamic scholars (Ulema) as having "reduced the Law of Islam practically to the state of immobility".[46]

The latter part of Iqbal's life was concentrated on political activity. He travelled across Europe and West Asia to garner political and financial support for the League, he reiterated the ideas of his 1932 address, and, during the Third round-Table Conference, he opposed the Congress and proposals for transfer of power without considerable autonomy or independence for Muslim provinces.

He would serve as president of the Punjab Muslim League, and would deliver speeches and publish articles in an attempt to rally Muslims across India as a single political entity. Iqbal consistently criticised feudal classes in Punjab as well as Muslim politicians averse to the League. Many unnoticed accounts of Iqbal's frustration toward Congress leadership were also pivotal in providing a vision for the two nation theory.

Patron of the Journal Tolu-e-Islam[edit]

Iqbal was the first patron of Tolu-e-Islam, a historical, political, religious and cultural journal of the Muslims of British India. In 1935, according to his instructions, Syed Nazeer Niazi initiated and edited the journal,[47] named after the famous poem of Iqbal, Tulu'i Islam. Niazi also dedicated the first edition of this journal to Iqbal. For a long time, Iqbal wanted a journal to propagate his ideas and the aims and objectives of the All India Muslim League. The journal played an important role in the Pakistan movement.[41]

Later, the journal was continued[48] by Ghulam Ahmed Pervez, who had already contributed many articles in its early editions.

Literary work[edit]

Persian[edit]

Iqbal's poetic works are written primarily in Persian rather than Urdu.[citation needed] Among his 12,000 verses of poetry, about 7,000 verses are in Persian.[citation needed] In 1915, he published his first collection of poetry, the Asrar-i-Khudi (Secrets of the Self) in Persian. The poems emphasise the spirit and self from a religious, spiritual perspective. Many critics have called this Iqbal's finest poetic work[49] In Asrar-e-Khudi, Iqbal explains his philosophy of "Khudi," or "Self."[8][20] Iqbal's use of the term "Khudi" is synonymous with the word "Rooh" mentioned in the Quran. "Rooh" is that divine spark which is present in every human being, and was present in Adam, for which God ordered all of the angels to prostrate in front of Adam. One has to make a great journey of transformation to realise that divine spirit.[8]

The same concept was used by Farid ud Din Attar in his "Mantaq-ul-Tair". He proves by various means that the whole universe obeys the will of the "Self." Iqbal condemns self-destruction. For him, the aim of life is self-realization and self-knowledge. He charts the stages through which the "Self" has to pass before finally arriving at its point of perfection, enabling the knower of the "Self" to become a vice-regent of God.[8]

In his Rumuz-i-Bekhudi (Hints of Selflessness), Iqbal seeks to prove the Islamic way of life is the best code of conduct for a nation's viability. A person must keep his individual characteristics intact, but once this is achieved he should sacrifice his personal ambitions for the needs of the nation. Man cannot realise the "Self" outside of society. Also in Persian and published in 1917, this group of poems has as its main themes the ideal community,[8] Islamic ethical and social principles, and the relationship between the individual and society. Although he is true throughout to Islam, Iqbal also recognises the positive analogous aspects of other religions. The Rumuz-i-Bekhudi complements the emphasis on the self in the Asrar-e-Khudi and the two collections are often put in the same volume under the title Asrar-i-Rumuz (Hinting Secrets). It is addressed to the world's Muslims.[8]

Iqbal's 1924 publication, the Payam-e-Mashriq (The Message of the East) is closely connected to the West-östlicher Diwan by the German poet Goethe. Goethe bemoans the West having become too materialistic in outlook, and expects the East will provide a message of hope to resuscitate spiritual values. Iqbal styles his work as a reminder to the West of the importance of morality, religion and civilisation by underlining the need for cultivating feeling, ardour and dynamism. He explains that an individual can never aspire to higher dimensions unless he learns of the nature of spirituality.[8] In his first visit to Afghanistan, he presented his book "Payam-e Mashreq" to King Amanullah Khan in which he admired the liberal movements of Afghanistan against the British Empire. In 1933, he was officially invited to Afghanistan to join the meetings regarding the establishment of Kabul University.[34]

The Zabur-e-Ajam (Persian Psalms), published in 1927, includes the poems Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed (Garden of New Secrets) and Bandagi Nama (Book of Slavery). In Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed, Iqbal first poses questions, then answers them with the help of ancient and modern insight, showing how it affects and concerns the world of action. Bandagi Nama denounces slavery by attempting to explain the spirit behind the fine arts of enslaved societies. Here as in other books, Iqbal insists on remembering the past, doing well in the present and preparing for the future, while emphasising love, enthusiasm and energy to fulfil the ideal life.[8]

Iqbal's 1932 work, the Javed Nama (Book of Javed) is named after and in a manner addressed to his son, who is featured in the poems. It follows the examples of the works of Ibn Arabi and Dante's The Divine Comedy, through mystical and exaggerated depictions across time. Iqbal depicts himself as Zinda Rud ("A stream full of life") guided by Rumi, "the master," through various heavens and spheres and has the honour of approaching divinity and coming in contact with divine illuminations. In a passage re-living a historical period, Iqbal condemns the Muslims who were instrumental in the defeat and death of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula of Bengal and Tipu Sultan of Mysore, respectively, by betraying them for the benefit of the British colonists, and thus delivering their country to the shackles of slavery. At the end, by addressing his son Javid, he speaks to the young people at large, and provides guidance to the "new generation."[8]

His love of the Persian language is evident in his works and poetry. He says in one of his poems:[50]

گرچہ ہندی در عذوبت شکر است[51]

garchi Hindi dar uzūbat shakkar ast

طرز گفتار دري شيرين تر است

tarz-i guftar-i Dari shirin tar ast

Translation: Even though in sweetness Hindi* is sugar – (but) speech method in Dari (Persian dialect) is sweeter *

Urdu[edit]

Iqbal's Bang-e-Dara (The Call of the Marching Bell), his first collection of Urdu poetry, was published in 1924. It was written in three distinct phases of his life.[8] The poems he wrote up to 1905—the year he left for England—reflect patriotism and the imagery of nature, including the Tarana-e-Hind (The song of India),[34] and Tarana-e-Milli (The song of the Community). The second set of poems date from 1905–1908, when Iqbal studied in Europe, and dwell upon the nature of European society, which he emphasised had lost spiritual and religious values. This inspired Iqbal to write poems on the historical and cultural heritage of Islam and the Muslim community, with a global perspective. Iqbal urges the entire Muslim community, addressed as the Ummah, to define personal, social and political existence by the values and teachings of Islam.[8]

Iqbal's works were in Persian for most of his career, but after 1930 his works were mainly in Urdu. His works in this period were often specifically directed at the Muslim masses of India, with an even stronger emphasis on Islam and Muslim spiritual and political reawakening. Published in 1935, the Bal-e-Jibril (Wings of Gabriel) is considered by many critics as his finest Urdu poetry, and was inspired by his visit to Spain, where he visited the monuments and legacy of the kingdom of the Moors. It consists of ghazals, poems, quatrains, epigrams and carries a strong sense of religious passion.[8]

The Pas Cheh Bayed Kard ai Aqwam-e-Sharq (What are we to do, O Nations of the East?) includes the poem Musafir (Traveler). Again, Iqbal depicts Rumi as a character and an exposition of the mysteries of Islamic laws and Sufi perceptions is given. Iqbal laments the dissension and disunity among the Indian Muslims as well as Muslim nations. Musafir is an account of one of Iqbal's journeys to Afghanistan, in which the Pashtun people are counselled to learn the "secret of Islam" and to "build up the self" within themselves.[8] Iqbal's final work was the Armughan-e-Hijaz (The Gift of Hijaz), published posthumously in 1938. The first part contains quatrains in Persian, and the second part contains some poems and epigrams in Urdu. The Persian quatrains convey the impression that the poet is travelling through the Hijaz in his imagination. Profundity of ideas and intensity of passion are the salient features of these short poems.[8]

Iqbal's vision of mystical experience is clear in one of his Urdu ghazals, which was written in London during his days of studying there. Some verses of that ghazal are:[8]

At last the silent tongue of Hijaz has

announced to the ardent ear the tiding

That the covenant which had been given to the

desert-[dwellers] is going to be renewed

vigorously:

The lion who had emerged from the desert and

had toppled the Roman Empire is

As I am told by the angels, about to get up

again (from his slumbers.)

You the [dwellers] of the West, should know that

the world of God is not a shop (of yours).

Your imagined pure gold is about to lose it

standard value (as fixed by you).

Your civilization will commit suicide with its own daggers.

For a house built on a fragile bark of wood is not longlasting[8]

English[edit]

Iqbal wrote two books on the topic of The Development of Metaphysics in Persia and The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam and many letters in the English language. In these, he revealed his thoughts regarding Persian ideology and Islamic Sufism – in particular, his beliefs that Islamic Sufism activates the searching soul to a superior perception of life. He also discussed philosophy, God and the meaning of prayer, human spirit and Muslim culture, as well as other political, social and religious problems.[8]

Iqbal was invited to Cambridge to participate in a conference in 1931, where he expressed his views, including those on the separation of church and state to participants which included the students of that university:[8]

I would like to offer a few pieces of advice to the youngmen who are at present studying at Cambridge. ... I advise you to guard against atheism and materialism. The biggest blunder made by Europe was the separation of Church and State. This deprived their culture of moral soul and diverted it to the atheistic materialism. I had twenty-five years ago seen through the drawbacks of this civilization and therefore, had made some prophecies. They had been delivered by my tongue although I did not quite understand them. This happened in 1907. ... After six or seven years, my prophecies came true, word by word. The European war of 1914 was an outcome of the aforesaid mistakes made by the European nations in the separation of the Church and the State.[8]

Punjabi[edit]

Iqbal also wrote some poems in Punjabi, such as Piyaara Jedi and Baba Bakri Wala, which he penned in 1929 on the occasion of his son Javid's birthday. A collection of his rarely known Punjabi poetry was put on display at the Iqbal Manzil in Sialkot.[52]

Iqbal known in subcontinent[edit]

As Poet of the East[edit]

Iqbal has been recognised and quoted as "Poet of the East" by academics, institutions and the media.[13][53][54][55][56][57][58]

The Vice-Chancellor of Quaid-e-Azam University, Dr. Masoom Yasinzai, described in a seminar addressing a distinguished gathering of educationists and intellectuals that Iqbal is not only a poet of the East, but is a universal poet. Moreover, Iqbal is not restricted to any specific segment of the world community but he is for the entire humanity.[59]

Yet it should also be born in mind that whilst dedicating his Eastern Divan to Goethe, the cultural icon par excellence, Iqbal's Payam-i-Mashriq constituted both a reply as well as a corrective to the Western Divan of Goethe. For by stylising himself as the representative of the East, Iqbal's endeavour was to talk on equal terms to Goethe as the representative of West."[60]

Iqbal's revolutionary works through his poetry awakened the Muslims of the subcontinent. Iqbal was confident that the Muslims had long been suppressed by the colonial enlargement and growth of the West. In this concept Iqbal is recognised as the "Poet of the East".[54][61][62]

So to conclude, let me cite Annemarie Schimmel in Gabriel's Wing who lauds Iqbal's 'unique way of weaving a grand tapestry of thought from eastern and western yarns' (p. xv), a creative activity which, to cite my own volume Revisioning Iqbal, endows Muhammad Iqbal with the stature of a "universalist poet" and thinker whose principal aim was to explore mitigating alternative discourses with a view to constructing a bridge between the 'East' and the 'West'.[60]

The Urdu world is very familiar to Iqbal as the "Poet of the East".[62] Iqbal is also called Muffakir-e-Pakistan, "The Thinker of Pakistan") and Hakeem-ul-Ummat "The Sage of the Ummah"). The Pakistan government officially named him a "national poet".[7]

Iqbal in Iran[edit]

In Iran, he is famous as Iqbāl-e Lāhorī (Iqbal of Lahore). Iqbal's "Asrare-i-Khudi" and "Bal-i-Jibreel" are known in Iran, while many scholars in Iran have recognised the importance of Iqbal's poetry in inspiring and sustaining the Iranian Revolution of 1979.[63][5] During the early phases of the revolutionary movement, it was common to see people gathering in a park or corner to listen to someone reciting Iqbal's Persian poetry, which is why people of all ages in Iran today are familiar with at least some of his poetry, notably "Az-zabur-e-Ajam".[64][5]

In his analysis of the Persian poetry of Muhammad Iqbal, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei states that "we have a large number of non-Persian-speaking poets in the history of our literature, but I cannot point out any of them whose poetry possesses the qualities of Iqbal's Persian poetry. Iqbal was not acquainted with Persian idiom, as he spoke Urdu at home and talked to his friends in Urdu or English. He did not know the rules of Persian prose writing."[65]

After the death of Iqbal in 1938, by the early 1950s, Iqbal became known among the intelligentsia of the academic circles of Iran. Iranian poet laureate Muhammad Taqi Bahar universalized Iqbal in Iran. He highly praised the work of Iqbal in Persian.

In 1952, the Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, a national hero because of his oil nationalisation policy, broadcast a special radio message on Iqbal Day and praised his role in the struggle of the Indian Muslims against British imperialism. At the end of the 1950s, Iranians published the complete works of Persian. In the 1960s, Iqbal's thesis on Persian philosophy was translated from English to Persian. Ali Shariati, a Sorbonne-educated sociologist, supported Iqbal as his role model as Iqbal had Rumi. It is the best example of admiration and appreciation of Iran that they gave him the place of honour in the pantheon of the Persian elegy writers.

In 1970, Iran realised Iqbal. Iqbal's verses appeared on the banners and his poetry was recited at meetings of the intellectuals. Iqbal inspired many intellectuals, including famous names Ali Shariati, Mehdi Bazargan, and Dr. Abdulkarim Soroush. His famous book "The reconstruction of religious thought in Islam" has been translated by Dr. Mohammad Masud Noruzi.[5]

Key Iranian thinkers and leaders who were influenced by Iqbal's poetry during the rise of the Iranian revolution include Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Ali Shariati, and Abdolkarim Soroush, although much of the revolutionary guard was intimately familiar with numerous verses of Iqbal's body of poetry.[66] In fact, at the inauguration of the First Iqbal Summit in Tehran (1986), the Supreme Leader of the Iranian Revolution, Ayatollah Khamenei, stated that in its 'conviction that the Quran and Islam are to be made the basis of all revolutions and movements', Iran was 'exactly following the path that was shown to us by Iqbal'.[66] Ali Shariati, who has been described as a core ideologue for the Iranian Revolution, described Iqbal as a figure who brought a message of "rejuvenation", "awakening" and "power" to the Muslim World.[67]

International influence[edit]

Iqbal and the West[edit]

Iqbal's views on the Western world were applauded by men including United States Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas, who said that Iqbal's beliefs had "universal appeal".[69] Soviet biographer N. P. Anikoy wrote:

[Iqbal is] great for his passionate condemnation of weak will and passiveness, his angry protest against inequality, discrimination and oppression in all forms i.e., economic, social, political, national, racial, religious, etc., his preaching of optimism, an active attitude towards life and man's high purpose in the world, in a word, he is great for his assertion of the noble ideals and principles of humanism, democracy, peace and friendship among peoples.[69]

Others, including Wilfred Cantwell Smith, stated that with Iqbal's anti-capitalist holdings he was 'anti-intellect', because "capitalism fosters intellect".[69] Professor Freeland Abbott objected to Iqbal's views, saying that Iqbal's view of the West was based on the role of imperialism and Iqbal was not immersed enough in Western culture to learn about the various benefits of the modern democracies, economic practices and science.[69] Critics of Abbot's viewpoint note that Iqbal was raised and educated in the European way of life, and spent enough time there to grasp the general concepts of Western civilisation.[69]

Gallery[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

Prose book in Urdu

- Ilm ul Iqtisad (1903)[8]

Prose books in English

- The Development of Metaphysics in Persia (1908)[7][8]

- The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (1930)[7][8]

Poetic books in Persian

- Asrar-i-Khudi (1915)[8]

- Rumuz-i-Bekhudi (1917)[8]

- Payam-i-Mashriq (1923)[8]

- Zabur-i-Ajam (1927)[8]

- Javid Nama (1932)[8]

- Pas Cheh Bayed Kard ai Aqwam-e-Sharq (1936)[8]

- Armughan-e-Hijaz (1938)[7][8][41] (in Persian and Urdu)

Poetic books in Urdu

- Bang-i-Dara (1924)[8]

- Bal-i-Jibril (1935)[8]

- Zarb-i Kalim (1936)[8]

See also[edit]

- Iblees Ki Majlis-e-Shura, a poem by Iqbal

- List of Pakistani poets

- List of Urdu language poets

- List of Muslim philosophers

- Iqbal Academy Pakistan

References[edit]

- ^ Rehman, Javaid (2005). Islamic State Practices, International Law and the Threat from Terrorism: A Critique of the 'Clash of Civilizations' in the New World Order. Bloomsbury Publishingr. p. 15. ISBN 9781841135014.

- ^ a b c "Allama Muhammad Iqbal Philosopher, poet, and Political leader". Aml.Org.pk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ al.], Albert M. Craig ... [et (2011). The heritage of world civilizations (9th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education. p. 800. ISBN 978-0-205-80347-7.

- ^ a b Anil Bhatti. "Iqbal and Goethe" (PDF). Yearbook of the Goethe Society of India. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2011.CS1 maint: Unfit url (link)

- ^ a b c d "Love letter to Persia". The Friday Times. 25 April 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 28 May 2003. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Welcome to Allama Iqbal Site".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar 1 in author list, Iqbal Academy (26 May 2006). "Allama Iqbal – Biography" (PHP). Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "No. 32782". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1922. p. 2.

- ^ "Iqbal's pro Kashmir approach". GroundReport.com. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b Samiuddin, Abida (2007). Encyclopaedic dictionary of Urdu literature (2 Vols. Set). Global Vision Publishing House. p. 304. ISBN 81-8220-191-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sharif, Imran (21 April 2011). "Allama Iqbal's 73rd death anniversary observed with reverence". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "Cam Diary: Oxford remembers the Cam man". Daily Times. 28 May 2003. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "National holiday November 9". Brecorder.com. 6 November 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ a b Javed Manzil[better source needed]

- ^ Mushtaq, Faraz. "Life of Allama Iqbal". International Iqbal Society (Formerly DISNA). Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ M. G. Chitkara (1998). Converts Do Not Make a Nation. APH Publishing. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-81-7024-982-5.

- ^ Iqbal's biography Zinda Rud by Javeed Iqbal page 22-23.

- ^ Sevea, Iqbal Singh (2012). The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-139-53639-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schimmel, Annemarie (1962). Gabriel's wing: a study into the religious ideas of Sir Muhammad Iqbal. Brill Archive. pp. 34–45.

- ^ Mir, Mustansir (2006). Iqbal. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-094-3.

- ^ Sharma, Jai Narain (2008). Encyclopædia of eminent thinkers, volume 17. Concept Publishing Company. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7022-684-0.

- ^ a b c d e f "Iqbal in years" (PHP). Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Mushtaq, Faraz. "Time line". International Iqbal Society (Formerly DISNA). Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ a b Taneja, V.R; Taneja, S. (2004). Educational thinkers. Atlantic Publisher. p. 151. ISBN 81-7156-112-8.

- ^ a b c d "New research on Iqbal". Dawn. 10 November 2003. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Muḥammad Saʻīd, Lahore: A Memoir, Vanguard Books (1989), p. 175

- ^ Harjap Singh Aujla, Khurshid Anwar, a prince among the music directors of the sub-continent and his exploits in British and Independent India, Khurshid Anwar Biography, Academy of the Punjab in North America website, Retrieved 29 September 2015

- ^ Fedele, Roberta (31 July 2013). "From grandfather to grandson: The legacy of Mohammed Iqbal". Saudi Gazette. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Shah, Sabir (4 October 2015). "Justice Javed Iqbal dies two days before his 91st birthday". The News. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Lansing, East; H-Bahai, Mi. (2001) [1908]. "The development of metaphysics in persia" (PDF). London Luzac and Company. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Mir, Mustansir (1990). Tulip in the desert: A selection of the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal. c.Hurts and Company, Publishers Ltd. London. p. 2. ISBN 978-967-5-06267-4.

- ^ Jackso, Roy (2006). Fifty key figures in Islam. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-415-35467-7.

- ^ a b c d Popp, Stephan (6 May 2010). "Muhammad Iqbal". Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1963). Gabriel's wing. Brill Archive. p. 39.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1962). Gabriel's Wing. Brill Archive. p. 55.

- ^ Azam, K.M., Hayat-e-Sadeed: Bani-e-Dar ul Islam Chaudhry Niaz Ali (A Righteous Life: Founder of Dar ul Islam Chaudhry Niaz Ali Khan), Lahore: Nashriyat, 2010 (583 pp., Urdu) ISBN 978-969-8983-58-1

- ^ Allama Iqbal’s 73rd death anniversary observed with reverence. Pakistan Today. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Javaid Manzil last residence of Allama Iqbal looking for visitors By: M Abid Ayub Archived 26 August 2011 at Wikiwix. Ilmkidunya.com. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Afzal, Rafique M. (2013). A History of the All-India Muslim League (1906–1947). Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-906735-0.

- ^ a b c d "Allama Iqbal – The Great Poet And Philosopher:". Bright PK.com. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ New Age Weekly. In Memory of Com Ranjoor

- ^ a b "Iqbal and Pakistan Movement". Allamaiqbal.com. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman, pp. 14

- ^ Naipaul, V. S. Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples. pp. 250–52.

- ^ The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (reprint ed.). Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications. 2004 [1934]. p. 131.

- ^ "Tolu-e-Islam – Under editorship of Syed Nazeer Niazi" (PDF). Archived from the original on August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Urdu Articles and Books". Tolueislam.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Official website, Allama Iqbal Academy. "Asrar-e-Khudi". Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- ^ Kuliyat Iqbal, Iqbal Academy Publications, 1990, Lahore, Pakistan

- ^ "1".

- ^ "Iqbal's Punjabi poetry put on display". The Nation. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Nation observes Allama Iqbal's 74th death anniversary". The Newstribe newspaper. 21 April 2012. Retrieved 13 Nov 2015.

- ^ a b "Feature: Allama Iqbal—the spiritual father of Pakistan". Daily Dawn. 8 November 2003. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Taus-Bolstad, Stacy (2008). Pakistan in Pictures. Lerner. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-58013-452-1.

- ^ Sheikh, Naveed Shahzad (2007). The New Politics of Islam: Pan-Islamic Foreign Policy in a World of States. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-415-44453-8.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (2000). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-415-22078-1.

- ^ Yahya, MD (2013). "Traditions of Patriotism in Urdu Poetry: A Critical Study with Special Reference to the Poet of the East Allama Iqbal and His Poetry" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary Research. 1 (2). ISSN 2319-5789. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Seminar on Allama Iqbal held at Preston University". Preston.Edu.PK. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ a b This document contains both interventions from Prof. Dharampal-Frick and Mrs. Al Sanyoura Baasiri- Gita Dharampal-Frick – (South Asia Institute, University of Heidelberg) (PDF). Orient Institut.Org. pp. 5–12. Retrieved 15 August 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Democracy in Islam: The Views of Several Modern Muslim Scholars. Amu-In Academia.Edu. p. 143. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ a b How to Read Iqbal (PDF). Urdu Studies.com. p. 2. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal". Osama Sajid. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ "Iqbal and the Iranians Iqbal". Nasir Riaz. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ "Iqbal". Khamenei.de. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ a b "The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal". Iqbal Singh Sevea. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ "Iqbal: Manifestation of the Islamic Spirit". Iqbal Singh Sevea. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ "Luxury edition of works by poet Muhammad Iqbal". University of Heidelberg. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Review, Iqbal (1985). "American, West European and Soviet Attitudes to Iqbal" (PHP). Retrieved 16 February 2012.

Further reading[edit]

- Shafique, Khurram Ali (2014). Iqbal: His Life and Our Times. ECO Cultural Institute & Iqbal Academy Pakistan. ISBN 978-0-9571416-6-7.

- Ram Nath, Kak (1995). Autumn Leaves: Kashmiri Reminiscences. India: Vitasta. ISBN 81-86588-00-0.

- Mustansir, Mir (2006), Iqbal, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-84511-094-3

- Muhammad, Munawwar. Iqbal-Poet Philosopher of Islam. ISBN 969-416-061-8.

- Sailen, Debnath. Secularism: Western and Indian. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. ISBN 978-81-269-1366-4.

- V.S., Naipaul (1998). Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples. USA: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50118-5.

- Annemarie, Schimmel (1963), Gabriel's Wing: a study of the religious ideas of Sir Muhammad Iqbal, Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill

- "Special report: The enduring vision of Iqbal 1877-1938". DAWN. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muhammad Iqbal. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Muhammad Iqbal |

- Muhammad Iqbal

- Leaders of the Pakistan Movement

- Pakistani revolutionaries

- Urdu poets

- Indian male poets

- Knights Bachelor

- Indian knights

- 20th-century Muslim scholars of Islam

- Government College University, Lahore alumni

- Heidelberg University alumni

- Persian-language poets

- Persian-language writers

- Islamic philosophers

- Contemporary Indian philosophers

- Kashmiri people

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Alumni of the Inns of Court School of Law

- Members of Lincoln's Inn

- Muhammad Iqbal family

- 20th-century philosophers

- 1877 births

- 1938 deaths

- People from Sialkot

- Punjabi people

- Writers from Lahore

- Urdu theologians

- Urdu children's writers

- Urdu letter writers

- Urdu writers from British India

- Urdu religious writers

- 20th-century Urdu writers

- Pakistan Movement

- National symbols of Pakistan

- Government College University, Lahore faculty

- Oriental College alumni

- Murray College alumni

- Indian Islamists

- Nondenominational Muslims

- Pakistani male poets

- 20th-century Indian poets

- 20th-century Pakistani poets