De vulgari eloquentia

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. (December 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

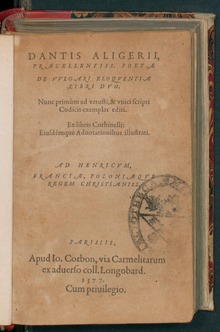

De vulgari eloquentia (Ecclesiastical Latin: [de vulˈɡari eloˈkwentsi.a], Classical Latin: [deː wʊɫˈɡaːriː eːɫɔˈkᶣɛnti.aː]; Italian: [de vulˈɡaːri eloˈkwɛntsja]; "On eloquence in the vernacular" (Italian: L'eloquenza in lingua volgare)) is the title of a Latin essay by Dante Alighieri. Although meant to consist of four books, its writing was abandoned in the middle of the second book. It was probably composed shortly after Dante went into exile; internal evidence points to a date between 1302 and 1305.

In the first book, Dante discusses the relationship between Latin and vernacular, and the search for an "illustrious" vernacular in the Italian area; the second book is an analysis of the structure of the canto or song (also spelled canzuni in Sicilian), which is a literary genre developed in the Sicilian School of poetry.

Latin essays were very popular in the Middle Ages, but Dante made some innovations in his work: firstly, the subject (writing in vernacular) was an uncommon topic in literary discussion at that time. Also significant was how Dante approached this theme; that is, he presented an argument for giving vernacular the same dignity and legitimacy Latin was typically given. Finally, Dante wrote this essay in order to analyse the origin and the philosophy of the vernacular, because, in his opinion, this language was not something static, but something that evolves and needed a historical contextualisation.

Structure[edit]

Dante interrupted his work at the fourteenth chapter of the second book, and though historians have tried to find a reason for this, it is still not known why Dante so abruptly aborted his essay. Indeed it is an unfinished project, and so information about its intended structure is limited. Though at some point, Dante mentions a fourth book in which he planned to deal with the comic genre and the "mediocre" style, nothing at all is known about the third book. It is thought, however, that the first book was meant to be a sort of preface to the following three books, and so shorter than the others.

Content[edit]

In the beginning, Dante tackles the historical evolution of language, which he thinks was born unitary and, at a later stage, was separated into different idioms because of the presumptuousness demonstrated by humankind at the time of the building of the Tower of Babel. He compiles a map of the geographical position of the languages he knows, dividing the European territory into three parts: one to the east, with the Greek languages; one to the north, with the Germanic languages, which he believed included Magyar and Slavic languages; one to the south, separated into three Romance languages identified by their word for 'yes': oc language, oïl language and sì language. He then discusses gramatica, "grammar", which is a static language consisting of unchanging rules, needed to make up for the natural languages. In chapters ten to fifteen of the first book, Dante writes about his search for the illustrious vernacular, among the fourteen varieties he claims to have found in the Italian region in Book 1 (X,VII): "Perciò è evidente che l'Italia sola si diversifica in almeno quattordici volgari".[1]

In the second book, Dante deals with literary genres, specifying which are the ones that suit the vernacular.

Models[edit]

Dante takes inspiration from rhetorical essays in Latin, Occitan, Sicilian, and Italian, and from philosophical readings. The main classical rhetorical texts from which he drew information were the Ars Poetica by Horace, the Rhetorica ad Herennium by an anonymous author, and De Inventione by Cicero. About the philosophical works, it is important to know that Dante read not only first hand texts, but also summaries that sometimes were not of the original work, but of an intermediary one. The influence and importance of the contribution of the Sicilian language is emphasized by his assertion that "the first hundred and fifty years of Italian poetry was written in Sicilian".

The major Occitan work that influenced Dante was probably Razos de trobar by the Catalan troubadour Raimon Vidal de Bezaudun and the Vers e regles de trobar, an amplification of Vidal's manual, by Jofre de Foixà.[2][3] Both of these works were Occitan manuals of grammar for troubadour poetry. They implicitly and explicitly defended Occitan as the best vernacular for song and verse, prompting Dante to come to the defence of his beloved Tuscan tongue. The popularity of both singing and composing in Occitan by Italians prompted Dante to write: A perpetuale infamia e depressione delli malvagi uomini d'Italia, che commendano lo volgare altrui, e lo loro proprio dispregiano, dico...,[4] meaning "To the perpetual shame and lowness of the wicked men of Italy, that praise somebody else's vernacular and despise their own, I say..." (Convivio, treatise I, XI).

Directly or indirectly, Dante came to read Saint Augustine's works, the De Consolatione Philosophiae by Boëthius, Saint Thomas Aquinas's works and some encyclopedic dictionaries like the Etymologiae by Isidore of Seville and the Livre du Tresor by Brunetto Latini. He takes also inspiration from Aristotelian philosophy, and references to texts by representatives of what is sometimes referred to as Radical Aristotelianism can be found in Dante's work.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (1948). De Vulgari Eloquentia. Felice Le Monnier. p. 87.

- ^ Ewert 1940, p. 357.

- ^ Weiss 1942, p. 160 n1.

- ^ Graham-Leigh 2005, pp. 32 and n130.

Sources[edit]

- Graham-Leigh, Elaine (2005). The Southern French Nobility and the Albigensian Crusade. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-129-5.

- Ewert, A. (July 1940). "Dante's Theory of Language". The Modern Language Review. 35 (3): 355–366.

- Weiss, R. (April 1942). "Links between the 'Convivio' and the 'De Vulgari Eloquentia'". The Modern Language Review. 37 (2.): 156–168.

- Dante Alighieri (1996) [1305]. Steven Botterill, ed. De vulgari eloquentia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.