Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

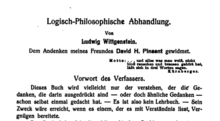

Title page of first English-language edition, 1922 | |

| Author | Ludwig Wittgenstein |

|---|---|

| Original title | Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung |

| Translator | Original English translation by Frank P. Ramsey and Charles Kay Ogden |

| Country | Austria |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Ideal language philosophy, logic and metaphysics |

| Publisher | First published in W. Ostwald's Annalen der Naturphilosophie |

Publication date | 1921 |

Published in English | Kegan Paul, 1922 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 75 |

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (widely abbreviated and cited as TLP) (Latin for Logical Philosophical Treatise or Treatise on Logic and Philosophy) is the only book-length philosophical work by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein that was published during his lifetime. The project had a broad goal: to identify the relationship between language and reality and to define the limits of science.[1] It is recognized by philosophers as a significant philosophical work of the twentieth century. G. E. Moore originally suggested the work's Latin title as homage to the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus by Baruch Spinoza.[2]

Wittgenstein wrote the notes for the Tractatus while he was a soldier during World War I and completed it during a military leave in the summer of 1918.[3] It was first published in German in 1921 as Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung. The Tractatus was influential chiefly amongst the logical positivist philosophers of the Vienna Circle, such as Rudolf Carnap and Friedrich Waismann. Bertrand Russell's article "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism" is presented as a working out of ideas that he had learned from Wittgenstein.[4]

The Tractatus employs an austere and succinct literary style. The work contains almost no arguments as such, but rather consists of declarative statements, or passages, that are meant to be self-evident. The statements are hierarchically numbered, with seven basic propositions at the primary level (numbered 1–7), with each sub-level being a comment on or elaboration of the statement at the next higher level (e.g., 1, 1.1, 1.11, 1.12, 1.13). In all, the Tractatus comprises 526 numbered statements.

Wittgenstein's later works, notably the posthumously published Philosophical Investigations, criticised many of his earlier ideas in the Tractatus.

Main theses[edit]

There are seven main propositions in the text. These are:

- The world is everything that is the case.

- What is the case (a fact) is the existence of states of affairs.

- A logical picture of facts is a thought.

- A thought is a proposition with a sense.

- A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions. (An elementary proposition is a truth-function of itself.)

- The general form of a proposition is the general form of a truth function, which is: . This is the general form of a proposition.

- Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Proposition 1[edit]

The first chapter is very brief:

- 1 The world is all that is the case.

- 1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

- 1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts.

- 1.12 For the totality of facts determines what is the case, and also whatever is not the case.

- 1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

- 1.2 The world divides into facts.

- 1.21 Each item can be the case or not the case while everything else remains the same.

This along with the beginning of two can be taken to be the relevant parts of Wittgenstein's metaphysical view that he will use to support his picture theory of language.

Propositions 2 and 3[edit]

These sections concern Wittgenstein's view that the sensible, changing world we perceive does not consist of substance but of facts. Proposition two begins with a discussion of objects, form and substance.

- 2 What is the case—a fact—is the existence of atomic facts.

- 2.01 An atomic fact is a combination of objects (entities, things).

This epistemic notion is further clarified by a discussion of objects or things as metaphysical substances.

- 2.0141 The possibility of its occurrence in atomic facts is the form of an object.

- 2.02 Objects are simple.

- ...

- 2.021 Objects make up the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite.

His use of the word "composite" in 2.021 can be taken to mean a combination of form and matter, in the Platonic sense.

The notion of a static unchanging Form and its identity with Substance represents the metaphysical view that has come to be held as an assumption by the vast majority of the Western philosophical tradition since Plato and Aristotle, as it was something they agreed on. "[W]hat is called a form or a substance is not generated."[5] (Z.8 1033b13) The opposing view states that unalterable Form does not exist, or at least if there is such a thing, it contains an ever changing, relative substance in a constant state of flux. Although this view was held by Greeks like Heraclitus, it has existed only on the fringe of the Western tradition since then. It is commonly known now only in "Eastern" metaphysical views where the primary concept of substance is Qi, or something similar, which persists through and beyond any given Form. The former view is shown to be held by Wittgenstein in what follows:

- 2.024 The substance is what subsists independently of what is the case.

- 2.025 It is form and content.

- ...

- 2.026 There must be objects, if the world is to have unalterable form.

- 2.027 Objects, the unalterable, and the substantial are one and the same.

- 2.0271 Objects are what is unalterable and substantial; their configuration is what is changing and unstable.

Although Wittgenstein largely disregarded Aristotle (Ray Monk's biography suggests that he never read Aristotle at all) it seems that they shared some anti-Platonist views on the universal/particular issue regarding primary substances. He attacks universals explicitly in his Blue Book. "The idea of a general concept being a common property of its particular instances connects up with other primitive, too simple, ideas of the structure of language. It is comparable to the idea that properties are ingredients of the things which have the properties; e.g. that beauty is an ingredient of all beautiful things as alcohol is of beer and wine, and that we therefore could have pure beauty, unadulterated by anything that is beautiful."[6]

And Aristotle agrees: "The universal cannot be a substance in the manner in which an essence is ..."[5] (Z.13 1038b17) as he begins to draw the line and drift away from the concepts of universal Forms held by his teacher Plato.

The concept of Essence, taken alone is a potentiality, and its combination with matter is its actuality. "First, the substance of a thing is peculiar to it and does not belong to any other thing"[5] (Z.13 1038b10), i.e. not universal and we know this is essence. This concept of form/substance/essence, which we've now collapsed into one, being presented as potential is also, apparently, held by Wittgenstein:

- 2.033 Form is the possibility of structure.

- 2.034 The structure of a fact consists of the structures of states of affairs.

- 2.04 The totality of existing states of affairs is the world.

- ...

- 2.063 The sum-total of reality is the world.

Here ends what Wittgenstein deems to be the relevant points of his metaphysical view and he begins in 2.1 to use said view to support his Picture Theory of Language. "The Tractatus's notion of substance is the modal analogue of Kant's temporal notion. Whereas for Kant, substance is that which 'persists' (i.e., exists at all times), for Wittgenstein it is that which, figuratively speaking, 'persists' through a 'space' of possible worlds."[7] Whether the Aristotelian notions of substance came to Wittgenstein via Immanuel Kant, or via Bertrand Russell, or even whether Wittgenstein arrived at his notions intuitively, one cannot but see them.

The further thesis of 2. and 3. and their subsidiary propositions is Wittgenstein's picture theory of language. This can be summed up as follows:

- The world consists of a totality of interconnected atomic facts, and propositions make "pictures" of the world.

- In order for a picture to represent a certain fact it must in some way possess the same logical structure as the fact. The picture is a standard of reality. In this way, linguistic expression can be seen as a form of geometric projection, where language is the changing form of projection but the logical structure of the expression is the unchanging geometric relationship.

- We cannot say with language what is common in the structures, rather it must be shown, because any language we use will also rely on this relationship, and so we cannot step out of our language with language.

Propositions 4.N to 5.N[edit]

The 4s are significant as they contain some of Wittgenstein's most explicit statements concerning the nature of philosophy and the distinction between what can be said and what can only be shown. It is here, for instance, that he first distinguishes between material and grammatical propositions, noting:

4.003 Most of the propositions and questions to be found in philosophical works are not false but nonsensical. Consequently we cannot give any answer to questions of this kind, but can only point out that they are nonsensical. Most of the propositions and questions of philosophers arise from our failure to understand the logic of our language. (They belong to the same class as the question whether the good is more or less identical than the beautiful.) And it is not surprising that the deepest problems are in fact not problems at all.

A philosophical treatise attempts to say something where nothing can properly be said. It is predicated upon the idea that philosophy should be pursued in a way analogous to the natural sciences; that philosophers are looking to construct true theories. This sense of philosophy does not coincide with Wittgenstein's conception of philosophy.

4.1 Propositions represent the existence and non-existence of states of affairs.

4.11 The totality of true propositions is the whole of natural science (or the whole corpus of the natural sciences).

4.111 Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences. (The word "philosophy" must mean something whose place is above or below the natural sciences, not beside them.)

4.112 Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts. Philosophy is not a body of doctrine but an activity. A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations. Philosophy does not result in "philosophical propositions", but rather in the clarification of propositions. Without philosophy thoughts are, as it were, cloudy and indistinct: its task is to make them clear and to give them sharp boundaries.

...

4.113 Philosophy sets limits to the much disputed sphere of natural science.

4.114 It must set limits to what can be thought; and, in doing so, to what cannot be thought. It must set limits to what cannot be thought by working outwards through what can be thought.

4.115 It will signify what cannot be said, by presenting clearly what can be said.

Wittgenstein is to be credited with the invention or at least the popularization of truth tables (4.31) and truth conditions (4.431) which now constitute the standard semantic analysis of first-order sentential logic.[8][9] The philosophical significance of such a method for Wittgenstein was that it alleviated a confusion, namely the idea that logical inferences are justified by rules. If an argument form is valid, the conjunction of the premises will be logically equivalent to the conclusion and this can be clearly seen in a truth table; it is displayed. The concept of tautology is thus central to Wittgenstein's Tractarian account of logical consequence, which is strictly deductive.

5.13 When the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, we can see this from the structure of the propositions.

5.131 If the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, this finds expression in relations in which the forms of the propositions stand to one another: nor is it necessary for us to set up these relations between them, by combining them with one another in a single proposition; on the contrary, the relations are internal, and their existence is an immediate result of the existence of the propositions.

...

5.132 If p follows from q, I can make an inference from q to p, deduce p from q. The nature of the inference can be gathered only from the two propositions. They themselves are the only possible justification of the inference. "Laws of inference", which are supposed to justify inferences, as in the works of Frege and Russell, have no sense, and would be superfluous.

Proposition 6.N[edit]

At the beginning of Proposition 6, Wittgenstein postulates the essential form of all sentences. He uses the notation , where

- stands for all atomic propositions,

- stands for any subset of propositions, and

- stands for the negation of all propositions making up .

Proposition 6 says that any logical sentence can be derived from a series of NOR operations on the totality of atomic propositions. Wittgenstein drew from Henry M. Sheffer's logical theorem making that statement in the context of the propositional calculus. Wittgenstein's N-operator is a broader infinitary analogue of the Sheffer stroke, which applied to a set of propositions produces a proposition that is equivalent to the denial of every member of that set. Wittgenstein shows that this operator can cope with the whole of predicate logic with identity, defining the quantifiers at 5.52, and showing how identity would then be handled at 5.53-5.532.

The subsidiaries of 6. contain more philosophical reflections on logic, connecting to ideas of knowledge, thought, and the a priori and transcendental. The final passages argue that logic and mathematics express only tautologies and are transcendental, i.e. they lie outside of the metaphysical subject's world. In turn, a logically "ideal" language cannot supply meaning, it can only reflect the world, and so, sentences in a logical language cannot remain meaningful if they are not merely reflections of the facts.

From Propositions 6.4-6.54, the Tractatus shifts its focus from primarily logical considerations to what may be considered more traditionally philosophical foci (God, ethics, meta-ethics, death, the will) and, less traditionally along with these, the mystical. The philosophy of language presented in the Tractatus attempts to demonstrate just what the limits of language are- to delineate precisely what can and cannot be sensically said. Among the sensibly sayable for Wittgenstein are the propositions of natural science, and to the nonsensical, or unsayable, those subjects associated with philosophy traditionally- ethics and metaphysics, for instance.[10] Curiously, on this score, the penultimate proposition of the Tractatus, proposition 6.54, states that once one understands the propositions of the Tractatus, he will recognize that they are senseless, and that they must be thrown away. Proposition 6.54, then, presents a difficult interpretative problem. If the so-called ‘picture theory’ of meaning is correct, and it is impossible to represent logical form, then the theory, by trying to say something about how language and the world must be for there to be meaning, is self-undermining. This is to say that the ‘picture theory’ of meaning itself requires that something be said about the logical form sentences must share with reality for meaning to be possible.[11] This requires doing precisely what the ‘picture theory’ of meaning precludes. It would appear, then, that the metaphysics and the philosophy of language endorsed by the Tractatus give rise to a paradox: for the Tractatus to be true, it will necessarily have to be nonsense by self-application; but for this self-application to render the propositions of the Tractatus nonsense (in the Tractarian sense), then the Tractatus must be true.[12]

There are three primarily dialectical approaches to solving this paradox[11] the traditionalist, or Ineffable-Truths View;[12] 2) the resolute, ‘new Wittgenstein’, or Not-All-Nonsense View;[12] 3) the No-Truths-At-All View.[12] The traditionalist approach to resolving this paradox is to hold that Wittgenstein accepted that philosophical statements could not be made, but that nevertheless, by appealing to the distinction between saying and showing, that these truths can be communicated by showing.[12] On the resolute reading, some of the propositions of the Tractatus are withheld from self-application, they are not themselves nonsense, but point out the nonsensical nature of the Tractatus. This view often appeals to the so-called ‘frame’ of the Tractatus, comprising the preface and propositions 6.54.[11] The No-Truths-At-All View states that Wittgenstein held the propositions of the Tractatus to be ambiguously both true and nonsensical, at once. While the propositions could not be, by self-application of the attendant philosophy of the Tractatus, true (or even sensical), it was only the philosophy of the Tractatus itself that could render them so. This is presumably what made Wittgenstein compelled to accept the philosophy of the Tractatus as specially having solved the problems of philosophy. It is the philosophy of the Tractatus, alone, that can solve the problems. Indeed, the philosophy of the Tractatus is for Wittgenstein, on this view, problematic only when applied to itself.[12]

At the end of the text Wittgenstein uses an analogy from Arthur Schopenhauer, and compares the book to a ladder that must be thrown away after one has climbed it.

Proposition 7[edit]

As the last line in the book, proposition 7 has no supplementary propositions. It ends the book with the proposition "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." („Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen.")

The picture theory[edit]

A prominent view set out in the Tractatus is the picture theory, sometimes called the picture theory of language. The picture theory is a proposed explanation of the capacity of language and thought to represent the world.[13]:p44 Although something need not be a proposition to represent something in the world, Wittgenstein was largely concerned with the way propositions function as representations.[13]

According to the theory, propositions can "picture" the world as being a certain way, and thus accurately represent it either truly or falsely.[13] If someone thinks the proposition, "There is a tree in the yard," then that proposition accurately pictures the world if and only if there is a tree in the yard.[13]:p53 One aspect of pictures which Wittgenstein finds particularly illuminating in comparison with language is the fact that we can directly see in the picture what situation it depicts without knowing if the situation actually obtains. This allows Wittgenstein to explain how false propositions can have meaning (a problem which Russell struggled with for many years): just as we can see directly from the picture the situation which it depicts without knowing if it in fact obtains, analogously, when we understand a proposition we grasp its truth conditions or its sense, that is, we know what the world must be like if it is true, without knowing if it is in fact true (TLP 4.024, 4.431).[14]

It is believed that Wittgenstein was inspired for this theory by the way that traffic courts in Paris reenact automobile accidents.[15]:p35 A toy car is a representation of a real car, a toy truck is a representation of a real truck, and dolls are representations of people. In order to convey to a judge what happened in an automobile accident, someone in the courtroom might place the toy cars in a position like the position the real cars were in, and move them in the ways that the real cars moved. In this way, the elements of the picture (the toy cars) are in spatial relation to one another, and this relation itself pictures the spatial relation between the real cars in the automobile accident.[13]:p45

Pictures have what Wittgenstein calls Form der Abbildung or pictorial form, which they share with what they depict. This means that all the logically possible arrangements of the pictorial elements in the picture correspond to the possibilities of arranging the things which they depict in reality.[16] Thus if the model for car A stands to the left of the model for car B, it depicts that the cars in the world stand in the same way relative to each other. This picturing relation, Wittgenstein believed, was our key to understanding the relationship a proposition holds to the world.[13] Although language differs from pictures in lacking direct pictorial mode of representation (e.g., it doesn't use colors and shapes to represent colors and shapes), still Wittgenstein believed that propositions are logical pictures of the world by virtue of sharing logical form with the reality which they represent (TLP 2.18-2.2). And that he thought, explains how we can understand a proposition without its meaning having been explained to us (TLP 4.02), we can directly see in the proposition what it represents as we see in the picture the situation which it depicts just by virtue of knowing its method of depiction: propositions show their sense (TLP 4.022).[17]

However, Wittgenstein claimed that pictures cannot represent their own logical form, they cannot say what they have in common with reality but can only show it (TLP 4.12-4.121). If representation consist in depicting an arrangement of elements in logical space, then logical space itself can't be depicted since it is itself not an arrangement of anything; rather logical form is a feature of an arrangement of objects and thus it can be properly expressed (that is depicted) in language by an analogous arrangement of the relevant signs in sentences (which contain the same possibilities of combination as prescribed by logical syntax), hence logical form can only be shown by presenting the logical relations between different sentences.[18][14]

Wittgenstein's conception of representation as picturing also allows him to derive two striking claims: that no proposition can be known a priori - there are no apriori truths (TLP 3.05), and that there is only logical necessity (TLP 6.37). Since all propositions, by virtue of being pictures, have sense independently of anything being the case in reality, we cannot see from the proposition alone whether it is true (as would be the case if it could be known apriori), but we must compare it to reality in order to know that it's true (TLP 4.031 "In the proposition a state of affairs is, as it were, put together for the sake of experiment."). And for similar reasons, no proposition is necessarily true except in the limiting case of tautologies, which Wittgenstein say lack sense (TLP 4.461). If a proposition pictures a state of affairs in virtue of being a picture in logical space, then a non-logical or metaphysical "necessary truth" would be a state of affairs which is satisfied by any possible arrangement of objects (since it is true for any possible state of affairs), but this means that the would-be necessary proposition would not depict anything as being so but will be true no matter what the world is actually like; but if that's the case, then the proposition cannot say anything about the world or describe any fact in it - it would not be correlated with any particular state of affairs, just like a tautology (TLP 6.37).[19][20]

Logical atomism[edit]

Although Wittgenstein did not use the term himself, his metaphysical view throughout the Tractatus is commonly referred to as logical atomism. While his logical atomism resembles that of Bertrand Russell, the two views are not strictly the same.[13]:p58

Russell's theory of descriptions is a way of logically analyzing sentences containing definite descriptions without presupposing the existence of an object satisfying the description. According to the theory, a statement like "There is a man to my left" should be analyzed into: "There is some x such that x is a man and x is to my left, and for any y, if y is a man and y is to my left, y is identical to x". If the statement is true, x refers to the man to my left.[21]

Whereas Russell believed the names (like x) in his theory should refer to things we can know directly by virtue of acquaintance, Wittgenstein didn't believe that there are any epistemic constraints on logical analyses: the simple objects are whatever is contained in the elementary propositions which can't be logically analyzed any further.[13]:p63

By objects, Wittgenstein did not mean physical objects in the world, but the absolute base of logical analysis, that can be combined but not divided (TLP 2.02–2.0201).[13] According to Wittgenstein's logico-atomistic metaphysical system, objects each have a "nature," which is their capacity to combine with other objects. When combined, objects form "states of affairs." A state of affairs that obtains is a "fact." Facts make up the entirety of the world. Facts are logically independent of one another, as are states of affairs. That is, one state of affair's (or fact's) existence does not allow us to infer whether another state of affairs (or fact) exists or does not exist.[13]:pp58–59

Within states of affairs, objects are in particular relations to one another.[13]:p59 This is analogous to the spatial relations between toy cars discussed above. The structure of states of affairs comes from the arrangement of their constituent objects (TLP 2.032), and such arrangement is essential to their intelligibility, just as the toy cars must be arranged in a certain way in order to picture the automobile accident.[13]

A fact might be thought of as the obtaining state of affairs that Madison is in Wisconsin, and a possible (but not obtaining) state of affairs might be Madison's being in Utah. These states of affairs are made up of certain arrangements of objects (TLP 2.023). However, Wittgenstein does not specify what objects are. Madison, Wisconsin, and Utah cannot be atomic objects: they are themselves composed of numerous facts.[13] Instead, Wittgenstein believed objects to be the things in the world that would correlate to the smallest parts of a logically analyzed language, such as names like x. Our language is not sufficiently (i.e., not completely) analyzed for such a correlation, so one cannot say what an object is.[13]:p60 We can, however, talk about them as "indestructible" and "common to all possible worlds."[13] Wittgenstein believed that the philosopher's job was to discover the structure of language through analysis.[15]:p38

Anthony Kenny provides a useful analogy for understanding Wittgenstein's logical atomism: a slightly modified game of chess.[13]: pp60–61 Just like objects in states of affairs, the chess pieces do not alone constitute the game—their arrangements, together with the pieces (objects) themselves, determine the state of affairs.[13]

Through Kenny's chess analogy, we can see the relationship between Wittgenstein's logical atomism and his picture theory of representation.[13]:p61 For the sake of this analogy, the chess pieces are objects, they and their positions constitute states of affairs and therefore facts, and the totality of facts is the entire particular game of chess.[13]

We can communicate such a game of chess in the exact way that Wittgenstein says a proposition represents the world.[13] We might say "WR/KR1" to communicate a white rook's being on the square commonly labeled as king's rook 1. Or, to be more thorough, we might make such a report for every piece's position.[13]

The logical form of our reports must be the same logical form of the chess pieces and their arrangement on the board in order to be meaningful. Our communication about the chess game must have as many possibilities for constituents and their arrangement as the game itself.[13] Kenny points out that such logical form need not strictly resemble the chess game. The logical form can be had by the bouncing of a ball (for example, twenty bounces might communicate a white rook's being on the king's rook 1 square). One can bounce a ball as many times as one wishes, which means the ball's bouncing has "logical multiplicity," and can therefore share the logical form of the game.[13]:p62 A motionless ball cannot communicate this same information, as it does not have logical multiplicity.[13]

Distinction between saying and showing[edit]

According to traditional reading of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein's views about logic and language led him to believe that some features of language and reality cannot be expressed in senseful language but only "shown" by the form of certain expressions. Thus for example, according to the picture theory, when a proposition is thought or expressed, the proposition represents reality (truly or falsely) by virtue of sharing some features with that reality in common. However, those features themselves is something Wittgenstein claimed we could not say anything about, because we cannot describe the relationship that pictures bear to what they depict, but only show it via fact stating propositions (TLP 4.121). Thus we cannot say that there is a correspondence between language and reality, but the correspondence itself can only be shown,[13]:p56 since our language is not capable of describing its own logical structure.[15]:p47

However, on the more recent "resolute" interpretation of the Tractatus (see below), the remarks on "showing" were not in fact an attempt by Wittgenstein to gesture at the existence of some ineffable features of language or reality, but rather, as Cora Diamond and James Conant have argued,[22] the distinction was meant to draw a sharp contrast between logic and descriptive discourse. On their reading, Wittgenstein indeed meant that some things are shown when we reflect on the logic of our language, but what is shown in not that something is the case, as if we could somehow think it (and thus understand what Wittgenstein tries to show us) but for some reason we just couldn't say it. As Diamond and Conant explain:[22]

Speaking and thinking are different from activities the practical mastery of which has no logical side; and they differ from activities like physics the practical mastery of which involves the mastery of content specific to the activity. On Wittgenstein’s view [...] linguistic mastery does not, as such, depend on even an inexplicit mastery of some sort of content. [...] The logical articulation of the activity itself can be brought more clearly into view, without that involving our coming to awareness that anything. When we speak about the activity of philosophical clarification, grammar may impose on us the use of ‘that’-clauses and ‘what’-constructions in the descriptions we give of the results of the activity. But, one could say, the final ‘throwing away of the ladder’ involves the recognition that that grammar of ‘what’-ness has been pervasively misleading us, even as we read through the Tractatus. To achieve the relevant sort of increasingly refined awareness of the logic of our language is not to grasp a content of any sort.

Similarly, Michael Kremer suggested that Wittgenstein's distinction between saying and showing could be compared with Gilbert Ryle's famous distinction between "knowing that" and "knowing how".[23] Just as practical knowledge or skill (such as riding a bike) is not reducible to propositional knowledge according to Ryle, Wittgenstein also thought that the mastery of the logic of our language is a unique practical skill that doesn't involve any sort of propositional "knowing that", but rather is reflected in our ability to operate with senseful sentences and grasping their internal logical relations.

Reception and influence[edit]

Philosophical[edit]

Wittgenstein concluded that the Tractatus had resolved all philosophical problems.[24]

The book was translated into English by C. K. Ogden with help from the teenaged Cambridge mathematician and philosopher Frank P. Ramsey. Ramsey later visited Wittgenstein in Austria. Translation issues make the concepts hard to pinpoint, especially given Wittgenstein's usage of terms and difficulty in translating ideas into words.[25]

The Tractatus caught the attention of the philosophers of the Vienna Circle (1921–1933), especially Rudolf Carnap and Moritz Schlick. The group spent many months working through the text out loud, line by line. Schlick eventually convinced Wittgenstein to meet with members of the circle to discuss the Tractatus when he returned to Vienna (he was then working as an architect). Although the Vienna Circle's logical positivists appreciated the Tractatus, they argued that the last few passages, including Proposition 7, are confused. Carnap hailed the book as containing important insights, but encouraged people to ignore the concluding sentences. Wittgenstein responded to Schlick, commenting: "...I cannot imagine that Carnap should have so completely misunderstood the last sentences of the book and hence the fundamental conception of the entire book."[26]

A more recent interpretation comes from The New Wittgenstein family of interpretations under development since 2000.[27] This so-called "resolute reading" is controversial and much debated.[citation needed] The main contention of such readings is that Wittgenstein in the Tractatus does not provide a theoretical account of language that relegates ethics and philosophy to a mystical realm of the unsayable. Rather, the book has a therapeutic aim. By working through the propositions of the book the reader comes to realize that language is perfectly suited to all his needs, and that philosophy rests on a confused relation to the logic of our language. The confusion that the Tractatus seeks to dispel is not a confused theory, such that a correct theory would be a proper way to clear the confusion, rather the need of any such theory is confused. The method of the Tractatus is to make the reader aware of the logic of our language as he is already familiar with it, and the effect of thereby dispelling the need for a theoretical account of the logic of our language spreads to all other areas of philosophy. Thereby the confusion involved in putting forward e.g. ethical and metaphysical theories is cleared in the same coup.

Wittgenstein would not meet the Vienna Circle proper, but only a few of its members, including Schlick, Carnap, and Waissman. Often, though, he refused to discuss philosophy, and would insist on giving the meetings over to reciting the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore with his chair turned to the wall. He largely broke off formal relations even with these members of the circle after coming to believe Carnap had used some of his ideas without permission.[28]

Alfred Korzybski credits Wittgenstein as an influence in his book, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics.[29]

Artistic[edit]

The Tractatus was the theme of a 1992 film by the Hungarian filmmaker Peter Forgacs. The 32-minute production, named Wittgenstein Tractatus, features citations from the Tractatus and other works by Wittgenstein.

In 1989 the Finnish artist M. A. Numminen released a black vinyl album, The Tractatus Suite, consisting of extracts from the Tractatus set to music, on the Forward! label (GN-95). The tracks were [T. 1] "The World is...", [T. 2] "In order to tell", [T. 4] "A thought is...", [T. 5] "A proposition is...", [T. 6] "The general form of a truth-function", and [T. 7] "Wovon man nicht sprechen kann". It was recorded at Finnvox Studios, Helsinki between February and June 1989. The "lyrics" were provided in German, English, Esperanto, French, Finnish and Swedish.[30] The music was reissued as a CD in 2003, M.A. Numminen sings Wittgenstein.[31]

Editions[edit]

The Tractatus is the English translation of:

- Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung, Wilhelm Ostwald (ed.), Annalen der Naturphilosophie, 14 (1921).

A notable German Edition of the works of Wittgenstein is:

- Werkausgabe (Vol. 1 includes the Tractatus). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Both English translations of the Tractatus, as well as the first publication in German from 1921, include an introduction by Bertrand Russell. Wittgenstein revised the Ogden translation.[32]

- C. K. Ogden (1922), prepared with assistance from G. E. Moore, F. P. Ramsey, and Wittgenstein. Routledge & Kegan Paul, parallel edition including the German text on the facing page to the English text: 1981 printing: ISBN 0-415-05186-X, 1999 Dover reprint

- David Pears and Brian McGuinness (1961), Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-7100-3004-5, 1974 paperback: ISBN 0-415-02825-6, 2001 hardcover: ISBN 0-415-25562-7, 2001 paperback: ISBN 0-415-25408-6

A manuscript version of the Tractatus, dubbed and published as the Prototractatus, was discovered in 1965 by Georg Henrik von Wright.[32]

Notes[edit]

- ^ TLP 4.113

- ^ Nils-Eric Sahlin, The Philosophy of F. P. Ramsey (1990), p. 227.

- ^ Monk p.154

- ^ Bertrand Russell (1918), "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism". The Monist. p. 177, as published, for example in Bertrand Russell (Robert Charles Marsh ed.) Logic and Knowledge Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-01-29.

- ^ a b c Aristotle's Metaphysics: © 1979 by H.G. Apostle Peripatetic Press. Des Moines, Iowa. Online translation: "The Internet Classics Archive | Metaphysics by Aristotle". Archived from the original on 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ "Blue Book on Universals citation". Blacksacademy.net. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ^ "Wittgenstein's Logical Atomism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ^ Grayling, A.C. Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford

- ^ Kneale, M. & Kneale, W. (1962), The Development of Logic

- ^ TLP 6.53

- ^ a b c Morris, Michael; Dodd, Julian (2009-06-01). "Mysticism and Nonsense in the Tractatus". European Journal of Philosophy. 17 (2): 247–276. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0378.2007.00268.x. ISSN 1468-0378.

- ^ a b c d e f Rowland), Morris, Michael (Michael (2008-01-01). Routledge philosophy guidebook to Wittgenstein and the Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Routledge. pp. 338–354. ISBN 9780203003091. OCLC 289386356.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Kenny 2005

- ^ a b Diamond, Cora (2013-06-20). Reading The Tractatus with G. E. M. Anscombe. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Analytic Philosophy. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199238842.001.0001. ISBN 9780199238842. Archived from the original on 2017-04-18.

- ^ a b c Stern 1995

- ^ Sullivan, Peter. A Version of the Picture Theory. pp. 90–91. Archived from the original on 2017-10-29.

- ^ Sullivan, Peter. A Version of the Picture Theory. pp. 108–109. Archived from the original on 2017-10-29.

- ^ Sullivan, Peter. A Version of the Picture Theory. p. 110. Archived from the original on 2017-10-29.

- ^ Ricketts, Thomas (1996). "Pictures, logic, and the limits of sense in Wittgenstein's Tractatus". The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein. pp. 87–89. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521460255.003. ISBN 9781139000697.

- ^ Diamond, Cora (1991). "Throwing Away the Ladder". The Realistic Spirit: Wittgenstein, Philosophy, and the Mind. MIT Press. pp. 192–193. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02.

- ^ "Descriptions (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ^ a b Conant, James; Diamond, Cora (2004). "On Reading the Tractatus Resolutely". In Kölbel, Max; Weiss, Bernhard. Wittgenstein's Lasting Significance. Routledge. pp. 65–67. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17.

- ^ Kremer, Michael (2007). "The Cardinal Problem of Philosophy". In Crary, Alice. Wittgenstein and the Moral Life: Essays in Honor of Cora Diamond. MIT Press. pp. 157–158. Archived from the original on 2016-08-02.

- ^ Biletzki, Anat & Matar, Anat (2002-11-08). "Ludwig Wittgenstein". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wittgenstein/#Bio: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Editorial Board.

- ^ Richard H. Popkin (November 1985), "Philosophy and the History of Philosophy", Journal of Philosophy, 82 (11): 625–632, doi:10.2307/2026418, JSTOR 2026418,

Many who knew Wittgenstein report that he found it extremely difficult to put his ideas into words and that he had many special usages of terms.

- ^ Conant, James F. "Putting Two and Two Together: Kierkegaard, Wittgenstein and the Point of View for Their Works as Authors", in Philosophy and the Grammar of Religious Belief (1995), ed. Timothy Tessin and Marion von der Ruhr, St. Martins Press, ISBN 0-312-12394-9

- ^ Crary, Alice M. and Rupert Read (eds.). The New Wittgenstein, Routledge, 2000.

- ^ Hintikka 2000, p. 55 cites Wittgenstein's accusation of Carnap upon receiving a 1932 preprint from Carnap.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-05-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "M.A. Numminen – The Tractatus Suite". Discogs.com. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Numminen, M. A. (2003). "M. A. Numminen Sings Wittgenstein. EFA SP 142". Zweitausendeins. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ a b R. W. Newell (January 1973), "Reviewed Work(s): Prototractatus, an Early Version of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus", Philosophy, 48 (183): 97–99, doi:10.1017/s0031819100060514, ISSN 0031-8191, JSTOR 3749717.

References[edit]

- Hintikka, Jaakko (2000), On Wittgenstein, ISBN 978-0-534-57594-6

- Kenny, Anthony (2005), Wittgenstein, Williston, VT: Wiley-Blackwell

- McManus, Denis (2006), The Enchantment of Words: Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Stern, David G. (1995), Wittgenstein on Mind and Language, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Ray Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Duty of Genius, Jonathan Cape, 1990.

- Zalabardo, José (2015). Representation and Reality in Wittgenstein's Tractatus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198743941.

External links[edit]

Online English versions

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Umass.edu, (Contains German, and Ogden and Pears & McGuinness translations side-by-side-by-side)

- Gutenberg.org (Ogden translation)

- TractatusLogico-Philosophicus (As a hierarchically nested document)

- Philosurfical.open.ac.uk Research software tool aimed at facilitating the study of the Tractatus. The text is available in German and in both English translations (Ogden & Pears-McGuinness)

- Graphical tabs-centered version of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (based on Pears & McGuinness translation)

- LibriVox audiobook version of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Ogden translation) (Version 1)

- LibriVox audiobook version of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Ogden translation) (Version 2)

- Tree-like version of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Ogden translation)

Online German versions

- Tractatus-Online.appspot.com

- Hochholzer.info

- Tractatus.Net

- KFS.org, Ogden translation (incomplete)

- Philosurfical.open.ac.uk

Visualization graphs

- Project TLP (Ogden translation / Data visualization graphs / English, German)

- Multilingual Tractatus Network (German, English, Russian, Spanish, French, Italian / Data visualization)

- University of Iowa Tractatus Map(Both the Tractatus and the Prototractatus presented in the style of a subway map / German and English)

- Wittgensteiniana (interactive visualizations of the Tractatus, English and German versions available)

![[\bar p,\bar\xi, N(\bar\xi)]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2280fc5b18f2a18924aeac15d592429f9a30389c)