Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek kryptós, "hidden", and analýein, "to loosen" or "to untie") is the study of analyzing information systems in order to study the hidden aspects of the systems.[1] Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic security systems and gain access to the contents of encrypted messages, even if the cryptographic key is unknown.

In addition to mathematical analysis of cryptographic algorithms, cryptanalysis includes the study of side-channel attacks that do not target weaknesses in the cryptographic algorithms themselves, but instead exploit weaknesses in their implementation.

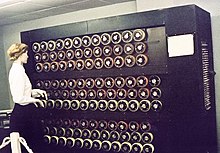

Even though the goal has been the same, the methods and techniques of cryptanalysis have changed drastically through the history of cryptography, adapting to increasing cryptographic complexity, ranging from the pen-and-paper methods of the past, through machines like the British Bombes and Colossus computers at Bletchley Park in World War II, to the mathematically advanced computerized schemes of the present. Methods for breaking modern cryptosystems often involve solving carefully constructed problems in pure mathematics, the best-known being integer factorization.

Contents

Overview[edit]

Given some encrypted data ("ciphertext"), the goal of the cryptanalyst is to gain as much information as possible about the original, unencrypted data ("plaintext"). It is useful to consider two aspects of achieving this. The first is breaking the system — that is discovering how the encipherment process works. The second is solving the key that is unique for a particular encrypted message or group of messages.

Amount of information available to the attacker[edit]

Attacks can be classified based on what type of information the attacker has available. As a basic starting point it is normally assumed that, for the purposes of analysis, the general algorithm is known; this is Shannon's Maxim "the enemy knows the system"[2] — in its turn, equivalent to Kerckhoffs' principle[3]. This is a reasonable assumption in practice — throughout history, there are countless examples of secret algorithms falling into wider knowledge, variously through espionage, betrayal and reverse engineering. (And on occasion, ciphers have been broken through pure deduction; for example, the German Lorenz cipher and the Japanese Purple code, and a variety of classical schemes):[4]

- Ciphertext-only: the cryptanalyst has access only to a collection of ciphertexts or codetexts.

- Known-plaintext: the attacker has a set of ciphertexts to which he knows the corresponding plaintext.

- Chosen-plaintext (chosen-ciphertext): the attacker can obtain the ciphertexts (plaintexts) corresponding to an arbitrary set of plaintexts (ciphertexts) of his own choosing.

- Adaptive chosen-plaintext: like a chosen-plaintext attack, except the attacker can choose subsequent plaintexts based on information learned from previous encryptions. Similarly Adaptive chosen ciphertext attack.

- Related-key attack: Like a chosen-plaintext attack, except the attacker can obtain ciphertexts encrypted under two different keys. The keys are unknown, but the relationship between them is known; for example, two keys that differ in the one bit.

Computational resources required[edit]

Attacks can also be characterised by the resources they require. Those resources include:[5]

- Time — the number of computation steps (e.g., test encryptions) which must be performed.

- Memory — the amount of storage required to perform the attack.

- Data — the quantity and type of plaintexts and ciphertexts required for a particular approach.

It's sometimes difficult to predict these quantities precisely, especially when the attack isn't practical to actually implement for testing. But academic cryptanalysts tend to provide at least the estimated order of magnitude of their attacks' difficulty, saying, for example, "SHA-1 collisions now 252."[6]

Bruce Schneier notes that even computationally impractical attacks can be considered breaks: "Breaking a cipher simply means finding a weakness in the cipher that can be exploited with a complexity less than brute force. Never mind that brute-force might require 2128 encryptions; an attack requiring 2110 encryptions would be considered a break...simply put, a break can just be a certificational weakness: evidence that the cipher does not perform as advertised."[7]

Partial breaks[edit]

The results of cryptanalysis can also vary in usefulness. For example, cryptographer Lars Knudsen (1998) classified various types of attack on block ciphers according to the amount and quality of secret information that was discovered:

- Total break — the attacker deduces the secret key.

- Global deduction — the attacker discovers a functionally equivalent algorithm for encryption and decryption, but without learning the key.

- Instance (local) deduction — the attacker discovers additional plaintexts (or ciphertexts) not previously known.

- Information deduction — the attacker gains some Shannon information about plaintexts (or ciphertexts) not previously known.

- Distinguishing algorithm — the attacker can distinguish the cipher from a random permutation.

Academic attacks are often against weakened versions of a cryptosystem, such as a block cipher or hash function with some rounds removed. Many, but not all, attacks become exponentially more difficult to execute as rounds are added to a cryptosystem,[8] so it's possible for the full cryptosystem to be strong even though reduced-round variants are weak. Nonetheless, partial breaks that come close to breaking the original cryptosystem may mean that a full break will follow; the successful attacks on DES, MD5, and SHA-1 were all preceded by attacks on weakened versions.

In academic cryptography, a weakness or a break in a scheme is usually defined quite conservatively: it might require impractical amounts of time, memory, or known plaintexts. It also might require the attacker be able to do things many real-world attackers can't: for example, the attacker may need to choose particular plaintexts to be encrypted or even to ask for plaintexts to be encrypted using several keys related to the secret key. Furthermore, it might only reveal a small amount of information, enough to prove the cryptosystem imperfect but too little to be useful to real-world attackers. Finally, an attack might only apply to a weakened version of cryptographic tools, like a reduced-round block cipher, as a step towards breaking of the full system.[7]

History[edit]

Cryptanalysis has coevolved together with cryptography, and the contest can be traced through the history of cryptography—new ciphers being designed to replace old broken designs, and new cryptanalytic techniques invented to crack the improved schemes. In practice, they are viewed as two sides of the same coin: secure cryptography requires design against possible cryptanalysis.[citation needed]

Successful cryptanalysis has undoubtedly influenced history; the ability to read the presumed-secret thoughts and plans of others can be a decisive advantage. For example, in England in 1587, Mary, Queen of Scots was tried and executed for treason as a result of her involvement in three plots to assassinate Elizabeth I of England. The plans came to light after her coded correspondence with fellow conspirators was deciphered by Thomas Phelippes.

In World War I, the breaking of the Zimmermann Telegram was instrumental in bringing the United States into the war. In World War II, the Allies benefitted enormously from their joint success cryptanalysis of the German ciphers — including the Enigma machine and the Lorenz cipher — and Japanese ciphers, particularly 'Purple' and JN-25. 'Ultra' intelligence has been credited with everything between shortening the end of the European war by up to two years, to determining the eventual result. The war in the Pacific was similarly helped by 'Magic' intelligence.[9]

Governments have long recognized the potential benefits of cryptanalysis for intelligence, both military and diplomatic, and established dedicated organizations devoted to breaking the codes and ciphers of other nations, for example, GCHQ and the NSA, organizations which are still very active today. In 2004, it was reported that the United States had broken Iranian ciphers. (It is unknown, however, whether this was pure cryptanalysis, or whether other factors were involved:[10]).

Classical ciphers[edit]

Although the actual word "cryptanalysis" is relatively recent (it was coined by William Friedman in 1920), methods for breaking codes and ciphers are much older. The first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis was given by 9th-century Arab[11][12] polymath, Al-Kindi (also known as "Alkindus" in Europe), in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages. This treatise includes a description of the method of frequency analysis (Ibrahim Al-Kadi, 1992- ref-3). Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta was author of a seminal work on cryptanalysis "De Furtivis Literarum Notis".[13]

Frequency analysis is the basic tool for breaking most classical ciphers. In natural languages, certain letters of the alphabet appear more often than others; in English, "E" is likely to be the most common letter in any sample of plaintext. Similarly, the digraph "TH" is the most likely pair of letters in English, and so on. Frequency analysis relies on a cipher failing to hide these statistics. For example, in a simple substitution cipher (where each letter is simply replaced with another), the most frequent letter in the ciphertext would be a likely candidate for "E". Frequency analysis of such a cipher is therefore relatively easy, provided that the ciphertext is long enough to give a reasonably representative count of the letters of the alphabet that it contains.[14]

In Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, the idea of a polyalphabetic substitution cipher was developed, among others by the French diplomat Blaise de Vigenère (1523–96).[15] For some three centuries, the Vigenère cipher, which uses a repeating key to select different encryption alphabets in rotation, was considered to be completely secure (le chiffre indéchiffrable—"the indecipherable cipher"). Nevertheless, Charles Babbage (1791–1871) and later, independently, Friedrich Kasiski (1805–81) succeeded in breaking this cipher.[16] During World War I, inventors in several countries developed rotor cipher machines such as Arthur Scherbius' Enigma, in an attempt to minimise the repetition that had been exploited to break the Vigenère system.[17]

Ciphers from World War I and World War II[edit]

Cryptanalysis of enemy messages played a significant part in the Allied victory in World War II. F. W. Winterbotham, quoted the western Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower, at the war's end as describing Ultra intelligence as having been "decisive" to Allied victory.[18] Sir Harry Hinsley, official historian of British Intelligence in World War II, made a similar assessment about Ultra, saying that it shortened the war "by not less than two years and probably by four years"; moreover, he said that in the absence of Ultra, it is uncertain how the war would have ended.[19]

In practice, frequency analysis relies as much on linguistic knowledge as it does on statistics, but as ciphers became more complex, mathematics became more important in cryptanalysis. This change was particularly evident before and during World War II, where efforts to crack Axis ciphers required new levels of mathematical sophistication. Moreover, automation was first applied to cryptanalysis in that era with the Polish Bomba device, the British Bombe, the use of punched card equipment, and in the Colossus computers — the first electronic digital computers to be controlled by a program.[20][21]

Indicator[edit]

With reciprocal machine ciphers such as the Lorenz cipher and the Enigma machine used by Nazi Germany during World War II, each message had its own key. Usually, the transmitting operator informed the receiving operator of this message key by transmitting some plaintext and/or ciphertext before the enciphered message. This is termed the indicator, as it indicates to the receiving operator how to set his machine to decipher the message.[22]

Poorly designed and implemented indicator systems allowed first Polish cryptographers[23] and then the British cryptographers at Bletchley Park[24] to break the Enigma cipher system. Similar poor indicator systems allowed the British to identify depths that led to the diagnosis of the Lorenz SZ40/42 cipher system, and the comprehensive breaking of its messages without the cryptanalysts seeing the cipher machine.[25]

Depth[edit]

Sending two or more messages with the same key is an insecure process. To a cryptanalyst the messages are then said to be "in depth."[26] This may be detected by the messages having the same indicator by which the sending operator informs the receiving operator about the key generator initial settings for the message.[27]

Generally, the cryptanalyst may benefit from lining up identical enciphering operations among a set of messages. For example, the Vernam cipher enciphers by bit-for-bit combining plaintext with a long key using the "exclusive or" operator, which is also known as "modulo-2 addition" (symbolized by ⊕ ):

- Plaintext ⊕ Key = Ciphertext

Deciphering combines the same key bits with the ciphertext to reconstruct the plaintext:

- Ciphertext ⊕ Key = Plaintext

(In modulo-2 arithmetic, addition is the same as subtraction.) When two such ciphertexts are aligned in depth, combining them eliminates the common key, leaving just a combination of the two plaintexts:

- Ciphertext1 ⊕ Ciphertext2 = Plaintext1 ⊕ Plaintext2

The individual plaintexts can then be worked out linguistically by trying probable words (or phrases), also known as "cribs," at various locations; a correct guess, when combined with the merged plaintext stream, produces intelligible text from the other plaintext component:

- (Plaintext1 ⊕ Plaintext2) ⊕ Plaintext1 = Plaintext2

The recovered fragment of the second plaintext can often be extended in one or both directions, and the extra characters can be combined with the merged plaintext stream to extend the first plaintext. Working back and forth between the two plaintexts, using the intelligibility criterion to check guesses, the analyst may recover much or all of the original plaintexts. (With only two plaintexts in depth, the analyst may not know which one corresponds to which ciphertext, but in practice this is not a large problem.) When a recovered plaintext is then combined with its ciphertext, the key is revealed:

- Plaintext1 ⊕ Ciphertext1 = Key

Knowledge of a key of course allows the analyst to read other messages encrypted with the same key, and knowledge of a set of related keys may allow cryptanalysts to diagnose the system used for constructing them.[25]

Development of modern cryptography[edit]

Even though computation was used to great effect in Cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher and other systems during World War II, it also made possible new methods of cryptography orders of magnitude more complex than ever before. Taken as a whole, modern cryptography has become much more impervious to cryptanalysis than the pen-and-paper systems of the past, and now seems to have the upper hand against pure cryptanalysis.[citation needed] The historian David Kahn notes:

Many are the cryptosystems offered by the hundreds of commercial vendors today that cannot be broken by any known methods of cryptanalysis. Indeed, in such systems even a chosen plaintext attack, in which a selected plaintext is matched against its ciphertext, cannot yield the key that unlock[s] other messages. In a sense, then, cryptanalysis is dead. But that is not the end of the story. Cryptanalysis may be dead, but there is - to mix my metaphors - more than one way to skin a cat.

— [28]

Kahn goes on to mention increased opportunities for interception, bugging, side channel attacks, and quantum computers as replacements for the traditional means of cryptanalysis. In 2010, former NSA technical director Brian Snow said that both academic and government cryptographers are "moving very slowly forward in a mature field."[29]

However, any postmortems for cryptanalysis may be premature. While the effectiveness of cryptanalytic methods employed by intelligence agencies remains unknown, many serious attacks against both academic and practical cryptographic primitives have been published in the modern era of computer cryptography:[citation needed]

- The block cipher Madryga, proposed in 1984 but not widely used, was found to be susceptible to ciphertext-only attacks in 1998.

- FEAL-4, proposed as a replacement for the DES standard encryption algorithm but not widely used, was demolished by a spate of attacks from the academic community, many of which are entirely practical.

- The A5/1, A5/2, CMEA, and DECT systems used in mobile and wireless phone technology can all be broken in hours, minutes or even in real-time using widely available computing equipment.

- Brute-force keyspace search has broken some real-world ciphers and applications, including single-DES (see EFF DES cracker), 40-bit "export-strength" cryptography, and the DVD Content Scrambling System.

- In 2001, Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP), a protocol used to secure Wi-Fi wireless networks, was shown to be breakable in practice because of a weakness in the RC4 cipher and aspects of the WEP design that made related-key attacks practical. WEP was later replaced by Wi-Fi Protected Access.

- In 2008, researchers conducted a proof-of-concept break of SSL using weaknesses in the MD5 hash function and certificate issuer practices that made it possible to exploit collision attacks on hash functions. The certificate issuers involved changed their practices to prevent the attack from being repeated.

Thus, while the best modern ciphers may be far more resistant to cryptanalysis than the Enigma, cryptanalysis and the broader field of information security remain quite active.[citation needed]

Symmetric ciphers[edit]

- Boomerang attack

- Brute-force attack

- Davies' attack

- Differential cryptanalysis

- Impossible differential cryptanalysis

- Improbable differential cryptanalysis

- Integral cryptanalysis

- Linear cryptanalysis

- Meet-in-the-middle attack

- Mod-n cryptanalysis

- Related-key attack

- Sandwich attack

- Slide attack

- XSL attack

Asymmetric ciphers[edit]

Asymmetric cryptography (or public key cryptography) is cryptography that relies on using two (mathematically related) keys; one private, and one public. Such ciphers invariably rely on "hard" mathematical problems as the basis of their security, so an obvious point of attack is to develop methods for solving the problem. The security of two-key cryptography depends on mathematical questions in a way that single-key cryptography generally does not, and conversely links cryptanalysis to wider mathematical research in a new way.[citation needed]

Asymmetric schemes are designed around the (conjectured) difficulty of solving various mathematical problems. If an improved algorithm can be found to solve the problem, then the system is weakened. For example, the security of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange scheme depends on the difficulty of calculating the discrete logarithm. In 1983, Don Coppersmith found a faster way to find discrete logarithms (in certain groups), and thereby requiring cryptographers to use larger groups (or different types of groups). RSA's security depends (in part) upon the difficulty of integer factorization — a breakthrough in factoring would impact the security of RSA.[citation needed]

In 1980, one could factor a difficult 50-digit number at an expense of 1012 elementary computer operations. By 1984 the state of the art in factoring algorithms had advanced to a point where a 75-digit number could be factored in 1012 operations. Advances in computing technology also meant that the operations could be performed much faster, too. Moore's law predicts that computer speeds will continue to increase. Factoring techniques may continue to do so as well, but will most likely depend on mathematical insight and creativity, neither of which has ever been successfully predictable. 150-digit numbers of the kind once used in RSA have been factored. The effort was greater than above, but was not unreasonable on fast modern computers. By the start of the 21st century, 150-digit numbers were no longer considered a large enough key size for RSA. Numbers with several hundred digits were still considered too hard to factor in 2005, though methods will probably continue to improve over time, requiring key size to keep pace or other methods such as elliptic curve cryptography to be used.[citation needed]

Another distinguishing feature of asymmetric schemes is that, unlike attacks on symmetric cryptosystems, any cryptanalysis has the opportunity to make use of knowledge gained from the public key.[30]

Attacking cryptographic hash systems[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2012) |

Side-channel attacks[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2012) |

- Black-bag cryptanalysis

- Man-in-the-middle attack

- Power analysis

- Replay attack

- Rubber-hose cryptanalysis

- Timing analysis

Quantum computing applications for cryptanalysis[edit]

Quantum computers, which are still in the early phases of research, have potential use in cryptanalysis. For example, Shor's Algorithm could factor large numbers in polynomial time, in effect breaking some commonly used forms of public-key encryption.[31]

By using Grover's algorithm on a quantum computer, brute-force key search can be made quadratically faster. However, this could be countered by doubling the key length.[32]

See also[edit]

- Economics of security

- Global surveillance

- Information assurance, a term for information security often used in government

- Information security, the overarching goal of most cryptography

- National Cipher Challenge

- Security engineering, the design of applications and protocols

- Security vulnerability; vulnerabilities can include cryptographic or other flaws

- Topics in cryptography

- Zendian Problem

Historic cryptanalysts[edit]

- Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander

- Charles Babbage

- Lambros D. Callimahos

- Joan Clarke

- Alastair Denniston

- Agnes Meyer Driscoll

- Elizebeth Friedman, co-inventor of modern cryptology[33]

- William F. Friedman, co-inventor of modern cryptology

- Meredith Gardner

- Friedrich Kasiski

- Al-Kindi

- Dilly Knox

- Solomon Kullback

- Marian Rejewski

- Joseph Rochefort, whose contributions affected the outcome of the Battle of Midway

- Frank Rowlett

- Abraham Sinkov

- Giovanni Soro, the Renaissance's first outstanding cryptanalyst

- John Tiltman

- Alan Turing

- William T. Tutte

- John Wallis - 17th-century English mathematician

- William Stone Weedon - worked with Fredson Bowers in World War II

- Herbert Yardley

References[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Cryptanalysis/Signals Analysis". Nsa.gov. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ^ Shannon, Claude (4 October 1949). "Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems". Bell System Technical Journal. 28: 662. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Kahn, David (1996), The Codebreakers: the story of secret writing (second ed.), Scribners, p. 235

- ^ Schmeh, Klaus (2003). Cryptography and public key infrastructure on the Internet. John Wiley & Sons. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-470-84745-9.

- ^ Hellman, M. (July 1980). "A cryptanalytic time-memory trade-off". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 26 (4): 401–406. doi:10.1109/tit.1980.1056220. ISSN 0018-9448 – via ACM.

- ^ McDonald, Cameron; Hawkes, Philip; Pieprzyk, Josef, SHA-1 collisions now 252 (PDF), retrieved 4 April 2012

- ^ a b Schneier 2000

- ^ For an example of an attack that cannot be prevented by additional rounds, see slide attack.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 4

- ^ "Breaking codes: An impossible task?". BBC News. June 21, 2004.

- ^ History of Islamic philosophy: With View of Greek Philosophy and Early history of Islam P.199

- ^ The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy P.279

- ^ Crypto History Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Singh 1999, p. 17

- ^ Singh 1999, pp. 45–51

- ^ Singh 1999, pp. 63–78

- ^ Singh 1999, p. 116

- ^ Winterbotham 2000, p. 229.

- ^ Hinsley 1993.

- ^ Copeland 2006, p. 1

- ^ Singh 1999, p. 244

- ^ Churchhouse 2002, pp. 33, 34

- ^ Budiansky 2000, pp. 97–99

- ^ Calvocoressi 2001, p. 66

- ^ a b Tutte 1998

- ^ Churchhouse 2002, p. 34

- ^ Churchhouse 2002, pp. 33, 86

- ^ David Kahn Remarks on the 50th Anniversary of the National Security Agency, November 1, 2002.

- ^ Tim Greene, Network World, Former NSA tech chief: I don't trust the cloud Archived 2010-03-08 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ Stallings, William (2010). Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0136097049.

- ^ "Shor's Algorithm – Breaking RSA Encryption". AMS Grad Blog. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2017-01-17.

- ^ Daniel J. Bernstein (2010-03-03). "Grover vs. McEliece" (PDF).

- ^ "Elizebeth S. Friedman". Hall of Honor. National Security Agency. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ibrahim A. Al-Kadi,"The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions", Cryptologia, 16(2) (April 1992) pp. 97–126.

- Friedrich L. Bauer: "Decrypted Secrets". Springer 2002. ISBN 3-540-42674-4

- Budiansky, Stephen (10 October 2000), Battle of wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II, Free Press, ISBN 978-0-684-85932-3

- Burke, Colin B. (2002). "It Wasn't All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s-1960s". Fort Meade: Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency.

- Calvocoressi, Peter (2001) [1980], Top Secret Ultra, Cleobury Mortimer, Shropshire: M & M Baldwin, ISBN 0-947712-41-0

- Churchhouse, Robert (2002), Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma and the Internet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00890-7

- Copeland, B. Jack, ed. (2006), Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4

- Helen Fouché Gaines, "Cryptanalysis", 1939, Dover. ISBN 0-486-20097-3

- David Kahn, "The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing", 1967. ISBN 0-684-83130-9

- Lars R. Knudsen: Contemporary Block Ciphers. Lectures on Data Security 1998: 105-126

- Schneier, Bruce (January 2000). "A Self-Study Course in Block-Cipher Cryptanalysis". Cryptologia. 24 (1): 18–34. doi:10.1080/0161-110091888754

- Abraham Sinkov, Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach, Mathematical Association of America, 1966. ISBN 0-88385-622-0

- Christopher Swenson, Modern Cryptanalysis: Techniques for Advanced Code Breaking, ISBN 978-0-470-13593-8

- Friedman, William F., Military Cryptanalysis, Part I, ISBN 0-89412-044-1

- Friedman, William F., Military Cryptanalysis, Part II, ISBN 0-89412-064-6

- Friedman, William F., Military Cryptanalysis, Part III, Simpler Varieties of Aperiodic Substitution Systems, ISBN 0-89412-196-0

- Friedman, William F., Military Cryptanalysis, Part IV, Transposition and Fractionating Systems, ISBN 0-89412-198-7

- Friedman, William F. and Lambros D. Callimahos, Military Cryptanalytics, Part I, Volume 1, ISBN 0-89412-073-5

- Friedman, William F. and Lambros D. Callimahos, Military Cryptanalytics, Part I, Volume 2, ISBN 0-89412-074-3

- Friedman, William F. and Lambros D. Callimahos, Military Cryptanalytics, Part II, Volume 1, ISBN 0-89412-075-1

- Friedman, William F. and Lambros D. Callimahos, Military Cryptanalytics, Part II, Volume 2, ISBN 0-89412-076-X

- Hinsley, F.H. (1993), Introduction: The influence of Ultra in the Second World War in Hinsley & Stripp 1993, pp. 1–13

- Singh, Simon (1999), The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography, London: Fourth Estate, pp. 143–189, ISBN 1-85702-879-1

- Smith, Michael (2000), The Emperor's Codes: Bletchley Park and the breaking of Japan's secret ciphers, London: Random House, ISBN 0-593-04641-2

- Tutte, W. T. (19 June 1998), Fish and I (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007, retrieved 7 October 2010 Transcript of a lecture given by Prof. Tutte at the University of Waterloo

- Winterbotham, F.W. (2000) [1974], The Ultra secret: the inside story of Operation Ultra, Bletchley Park and Enigma, London: Orion Books Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7528-3751-2, OCLC 222735270

Further reading[edit]

- Bard, Gregory V. (2009). Algebraic Cryptanalysis. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-1019-6.

- Hinek, M. Jason (2009). Cryptanalysis of RSA and Its Variants. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7518-2.

- Joux, Antoine (2009). Algorithmic Cryptanalysis. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7002-6.

- Junod, Pascal; Canteaut, Anne (2011). Advanced Linear Cryptanalysis of Block and Stream Ciphers. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-60750-844-1.

- Stamp, Mark & Low, Richard (2007). Applied Cryptanalysis: Breaking Ciphers in the Real World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-11486-5.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- Sweigart, Al (2013). Hacking Secret Ciphers with Python. Al Sweigart. ISBN 978-1482614374.

- Swenson, Christopher (2008). Modern cryptanalysis: techniques for advanced code breaking. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-13593-8.

- Wagstaff, Samuel S. (2003). Cryptanalysis of number-theoretic ciphers. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-153-7.

External links[edit]

| Look up cryptanalysis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cryptanalysis. |

- Basic Cryptanalysis (files contain 5 line header, that has to be removed first)

- Distributed Computing Projects

- List of tools for cryptanalysis on modern cryptography

- Simon Singh's crypto corner

- The National Museum of Computing

- UltraAnvil tool for attacking simple substitution ciphers

- How Alan Turing Cracked The Enigma Code Imperial War Museums