Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler | |

|---|---|

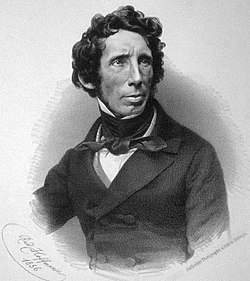

Friedrich Wöhler c. 1856, age 56 | |

| Born | 31 July 1800 |

| Died | 23 September 1882 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Wöhler synthesis of urea |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1872) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic chemistry Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Polytechnic School in Berlin Polytechnic School at Kassel University of Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisor | Leopold Gmelin Jöns Jakob Berzelius |

| Doctoral students | Heinrich Limpricht Rudolph Fittig Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe Georg Ludwig Carius Albert Niemann Vojtěch Šafařík Carl Schmidt Theodor Zincke |

| Other notable students | Augustus Voelcker[1] Wilhelm Kühne |

Friedrich Wöhler (German: [ˈvøːlɐ]; 31 July 1800 – 23 September 1882) was a German chemist, best known for his synthesis of urea, but also the first to isolate several chemical elements.

Contents

Biography[edit]

He was born in Eschersheim, which belonged to Hanau at the time but is nowadays a district of Frankfurt am Main. In 1823 Wöhler finished his study of medicine in Heidelberg at the laboratory of Leopold Gmelin, who arranged for him to work under Jöns Jakob Berzelius in Stockholm, Sweden. He taught chemistry from 1826 to 1831 at the Polytechnic School in Berlin until 1839 when he was stationed at the Polytechnic School at Kassel. Afterwards, he became Ordinary Professor of Chemistry in the University of Göttingen, where he remained until his death in 1882. In 1834, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Contributions to chemistry[edit]

Wöhler is regarded as a pioneer in organic chemistry as a result of his (accidentally) synthesizing urea from ammonium cyanate in the Wöhler synthesis in 1828.[2] In a letter to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius the same year, he wrote, 'In a manner of speaking, I can no longer hold my chemical water. I must tell you that I can make urea without the use of kidneys of any animal, be it man or dog.'[3]

This discovery has become celebrated as a refutation of vitalism, the hypothesis that living things are alive because of some special "vital force". However, contemporary accounts do not support that notion. This Wöhler Myth, as historian of science Peter J. Ramberg called it, originated from a popular history of chemistry published in 1931, which, "ignoring all pretense of historical accuracy, turned Wöhler into a crusader who made attempt after attempt to synthesize a natural product that would refute vitalism and lift the veil of ignorance, until 'one afternoon the miracle happened'".[4] Nevertheless, it was the beginning of the end of one popular vitalist hypothesis, that of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, that "organic" compounds could be made only by living things.

Major works, discoveries and research[edit]

Wöhler was also known for being a co-discoverer of beryllium, silicon and silicon nitride,[5] as well as the synthesis of calcium carbide, among others. In 1834, Wöhler and Justus Liebig published an investigation of the oil of bitter almonds. They proved by their experiments that a group of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms can behave like an element, take the place of an element, and be exchanged for elements in chemical compounds. Thus the foundation was laid of the doctrine of compound radicals, a doctrine which had a profound influence on the development of chemistry.

Since the discovery of potassium by Humphry Davy, it had been assumed that alumina, the basis of clay, contained a metal in combination with oxygen. Davy, Ørsted, and Berzelius attempted the extraction of this metal, but failed. Wöhler then worked on the same subject, and discovered the metal aluminium in 1827. To him also is due the isolation of the elements yttrium, beryllium, and titanium, the observation that "silicium" (silicon) can be obtained in crystals, and that some meteoric stones contain organic matter. He analyzed meteorites, and for many years wrote the digest on the literature of meteorites in the Jahresberichte über die Fortschritte der Chemie; he possessed the best private collection of meteoric stones and irons existing. Wöhler and Sainte Claire Deville discovered the crystalline form of boron, and Wöhler and Heinrich Buff discovered silane in 1856. Wöhler also prepared urea, a constituent of urine, from ammonium cyanate in the laboratory without the help of a living cell.

Final days and legacy[edit]

Wöhler's discoveries had great influence on the theory of chemistry. The journals of every year from 1820 to 1881 contain contributions from him. In the Scientific American supplement for 1882, it was remarked that "for two or three of his researches he deserves the highest honor a scientific man can obtain, but the sum of his work is absolutely overwhelming. Had he never lived, the aspect of chemistry would be very different from that it is now".[6]

Wöhler had several students who became notable chemists. Among them were Georg Ludwig Carius, Heinrich Limpricht, Rudolph Fittig, Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe, Albert Niemann, and Vojtěch Šafařík.

Further works[edit]

Further works from Wöhler:

- Lehrbuch der Chemie, Dresden, 1825, 4 vols.

- Grundriss der Anorganischen Chemie, Berlin, 1830

- Grundriss der Chemie, Berlin, 1837–1858 Vol.1&2 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Grundriss der Organischen Chemie, Berlin, 1840

- Praktische Übungen in der Chemischen Analyse, Berlin, 1854

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Goddard, Nicholas (2004). "Voelcker, (John Christopher) Augustus (1822–1884)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28345. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource:

. Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

. Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Wöhler, Friedrich (1828). "Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 88 (2): 253–256. Bibcode:1828AnP....88..253W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280880206. — Available in English at: "Chem Team".

- ^ Chemie heute, Schroedel Verlag, Klasse 9/10. Chapter 3: Chemie der Kohlenwasserstoffe. Excursus pg. 64, ISBN 978-3-507-86192-3. Translated from original: „Ich kann, so zu sagen, mein chemisches Wasser nicht halten und muss ihnen sagen, daß ich Harnstoff machen kann, ohne dazu Nieren oder überhaupt ein Thier, sey es Mensch oder Hund, nöthig zu haben.“

- ^ "Ramberg (2000), following Rocke (1993), pp. 239–241, traced back the origin to H. Kopp’s Geschichte der Chemie, Vol. 1 (1843), p. 442; vol. 4 (1847), p. 244. The myth was unmasked by McKie in 1944, followed by a series of papers quoted by Ramberg" (Schummer 2003, p. 718).

- ^ Deville, H.; Wohler, F. (1857). "Erstmalige Erwähnung von Si3N4". Liebigs Ann. Chem. 104: 256.

- ^ Scientific American Supplement No. 362, 9 Dec 1882. Fullbooks.com. Retrieved on 28 May 2014.

References[edit]

- Ramberg, Peter J. (2000). "The Death of Vitalism and the Birth of Organic Chemistry". Ambix. 47 (3): 170–195. doi:10.1179/000269800790987401.

- Schummer, Joachim (2003). "The notion of nature in chemistry" (PDF). Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. 34: 705–736. doi:10.1016/s0039-3681(03)00050-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Uray, Johannes (2009). "Mythos Harnstoffsynthese". Nachrichten aus der Chemie. 57: 943–944. doi:10.1002/nadc.200966159.

- Johannes Uray: Die Wöhlersche Harnstoffsynthese und das wissenschaftliche Weltbild. Graz, Leykam, 2009.

- Robin Keen: The Life and Work of Friedrich Wöhler. Bautz 2005.

- Hoppe, Brigitte (2007). "Review of The life and work of Friedrich Wohler (1800–1882) by Robin Keen, edited by Johannes Buttner". Isis. 98 (1): 195–196. doi:10.1086/519116.

- Johannes Valentin: Friedrich Wöhler. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart ("Grosse Naturforscher" 7) 1949.

- Georg Schwedt: Der Chemiker Friedrich Wöhler. Hischymia 2000.

- Brooke, John H. (1968). "Wöhler's Urea and its Vital Force – a verdict from the Chemists". Ambix. 15: 84–114. doi:10.1179/000269868791519757.

- Kauffman, George B.; Chooljian, Steven H. (2001). "Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882), on the Bicentennial of His Birth". The Chemical Educator. 6 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1007/s00897010444a.

- McKie, Douglas (1944). "Wöhler's syntethic Urea and the rejection of Vitalism: a chemical Legend". Nature. 153: 608–610. Bibcode:1944Natur.153..608M. doi:10.1038/153608a0.

- Ramberg, Peter J. (2000). "The Death of Vitalism and the Birth of organic Chemistry. Wöhler's Urea Synthesis and the disciplinary Identity of organic Chemistry". Ambix. 47: 170–215. doi:10.1179/000269800790987401.

- Uray, Johannes (2010). "Die Wöhlersche Harnstoffsynhtese und das Wissenschaftliche Weltbild – Analyse eines Mythos". Mensch, Wissenschaft, Magie. 27: 121–152.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Friedrich Wöhler. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Friedrich Wöhler |

Joy, Charles A. (August 1880). . Popular Science Monthly. 17.

Joy, Charles A. (August 1880). . Popular Science Monthly. 17. . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

. New International Encyclopedia. 1905. Dittmar, William (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (9th ed.).

Dittmar, William (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (9th ed.). . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.- Works by or about Friedrich Wöhler at Internet Archive

- 1800 births

- 1882 deaths

- Discoverers of chemical elements

- German chemists

- University of Marburg alumni

- Heidelberg University alumni

- University of Göttingen faculty

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Corresponding Members of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- People from Frankfurt

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- 19th-century German people

- 19th-century chemists