Levetiracetam

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /lɛvɪtɪˈræsɪtæm/ | ||

| Trade names | Keppra, Elepsia, other | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| MedlinePlus | a699059 | ||

| License data |

| ||

| Pregnancy category | |||

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | ~100% | ||

| Protein binding | <10% | ||

| Metabolism | Enzymatic hydrolysis of acetamide group | ||

| Elimination half-life | 6–8 hrs | ||

| Excretion | Urinary | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.121.571 | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

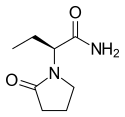

| Formula | C8H14N2O2 | ||

| Molar mass | 170.209 g/mol g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| |||

| |||

| | |||

Levetiracetam, marketed under the trade name Keppra among others, is a medication used to treat epilepsy.[1] It is used for partial onset, myoclonic, or tonic-clonic seizures.[2] It is taken by mouth as an immediate release or extended release formulation or by injection into a vein.[3]

Common side effects include sleepiness, dizziness, feeling tired, and aggression.[3] Severe side effects may include psychosis, suicide, and allergic reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and anaphylaxis.[3] It is the S-enantiomer of etiracetam.

Levetiracetam was approved for medical use in the United States in 1999.[3] The immediate release tablet has been available as a generic in the United States since 2008, and in the UK since 2011.[4][5] The patent for the extended release tablet will expire in 2028.[6] In 2016 it was the 89th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 8 million prescriptions.[7]

Contents

Medical uses[edit]

Levetiracetam has been approved in the United States as add-on treatment for partial (focal), myoclonic, and tonic-clonic seizures.[2] Levetiracetam has been approved in the European Union as a monotherapy treatment for epilepsy in the case of partial seizures, or as an adjunctive therapy for partial, myoclonic, and tonic-clonic seizures.[8] Levetiracetam has been shown to reduce partial (focal) seizures by 50% or more as an add-on medication.[5] It is also used in veterinary medicine for similar purposes. Based on low-quality evidence, levetiracetam is about as effective as phenytoin for prevention of early seizures after traumatic brain injury.[9]

Levetiracetam is sometimes used off-label to treat status epilepticus[10][11] or to prevent seizures associated with subarachnoid hemorrhages.[12]

Levetiracetam has potential benefits for other psychiatric and neurologic conditions such as Tourette syndrome,[13] anxiety disorder,[14] and Alzheimer's disease.[15] However, its most serious adverse effects are behavioral, and its benefit-risk ratio in these conditions is not well understood.[14]

Levetiracetam has not been found to be useful for treatment of neuropathic pain,[16] nor for treatment of essential tremors.[17] Levetiracetam has not been found to be useful for treating autism,[18][19] but is an effective treatment for partial, myoclonic, or tonic-clonic seizures associated with autism spectrum disorder.[20]

Pregnancy[edit]

Levetiracetam is a pregnancy category C drug. Studies in female pregnant rats have shown minor fetal skeletal abnormalities when given maximum recommended human doses of levetiracetam orally throughout pregnancy and lactation.[14]

Elderly[edit]

Studies were conducted to look for increased adverse effects in the elderly population as compared to younger patients. One such study published in Epilepsy Research showed no significant increase in incidence of adverse symptoms experienced by young or elderly patients with central nervous system (CNS) disorders.[16]

Children[edit]

Levetiracetam may be safely used with caution in children over the age of 4. However, it has not been determined whether it can be safely given to children under the age of 4.[21]

Kidney impairment[edit]

Kidney impairment decreases the rate of elimination of levetiracetam from the body. Individuals with reduced kidney function may require dose adjustments. Kidney function can be estimated from the rate of creatinine clearance.[22]

Liver impairment[edit]

Dose adjustment of levetiracetam is not necessary in liver impairment.[22]

Adverse effects[edit]

The most common adverse effects of levetiracetam treatment include CNS effects such as somnolence, decreased energy, headache, dizziness, mood swings and coordination difficulties. These adverse effects are most pronounced in the first month of therapy. About 4% of patients dropped out of pre-approval clinical trials due to these side effects.[22]

About 13% of people taking levetiracetam experience adverse neuropsychiatric symptoms, which are usually mild. These include agitation, hostility, apathy, anxiety, emotional lability, and depression. Serious psychiatric adverse side effects that are reversed by drug discontinuation occur in about 1%. These include hallucinations, suicidal thoughts, or psychosis. These occurred mostly within the first month of therapy, but they could develop at any time during treatment.[23]

Although rare, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), which appears as a painful spreading rash with redness and blistering and/or peeling skin, have been reported in patients treated with levetiracetam.[24] The incidence of SJS following exposure to anti-epileptics such as levetiracetam is about 1 in 3,000.[25]

Levetiracetam should not be used in people who have previously shown hypersensitivity to levetiracetam or any of the inactive ingredients in the tablet or oral solution. Such hypersensitivity reactions include, but are not limited to, unexplained rash with redness or blistered skin, difficulty breathing, and tightness in the chest or airways.[22]

In a study, the incidence of decreased bone mineral density of patients on levetiracetam was significantly higher than those for other epileptic medications.[26]

Suicide[edit]

Levetiracetam, along with other anti-epileptic drugs, can increase the risk of suicidal behavior or thoughts. People taking levetiracetam should be monitored closely for signs of worsening depression, suicidal thoughts or tendencies, or any altered emotional or behavioral states.[2]

Drug interactions[edit]

No significant pharmacokinetic interactions were observed between levetiracetam or its major metabolite and concomitant medications.[27] The pharmacokinetic profile of levetiracetam is not influenced by phenytoin, phenobarbital, primidone, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lamotrigine, gabapentin, digoxin, ethinylestradiol, or warfarin.[28]

Mechanism of action[edit]

The exact mechanism by which levetiracetam acts to treat epilepsy is unknown. However, the drug binds to SV2A,[29] a synaptic vesicle glycoprotein, and inhibits presynaptic calcium channels,[30] reducing neurotransmitter release and acting as a neuromodulator. This is believed to impede impulse conduction across synapses.[31]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

Absorption[edit]

The absorption of levetiracetam tablets and oral solution is rapid and essentially complete. The bioavailability of levetiracetam is close to 100 percent, and the effect of food on absorption is minor.[22]

Distribution[edit]

The volume of distribution of levetiracetam is similar to total body water. Levetiracetam modestly binds to plasma proteins (less than 10%).[22]

Metabolism[edit]

Levetiracetam does not undergo extensive metabolism, and the metabolites formed are not active and do not exert pharmacological activity. Metabolism of levetiracetam is not by liver cytochrome P450 enzymes, but through other metabolic pathways such as hydrolysis and hydroxylation.[22]

Excretion[edit]

Levetiracetam is eliminated from the body primarily by the kidneys with about 66 percent of the original drug passed unchanged into urine. The plasma half-life of levetiracetam in adults is about 6 to 8 hours.[22]

Available forms[edit]

Levetiracetam is available as regular and extended release oral formulations and as intravenous formulations.[22][32]

The branded version Keppra is manufactured by UCB Pharmaceuticals Inc.[33]

In 2015 Aprecia’s 3d-printed form of the drug was approved by the FDA.[34]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Abou-Khalil B (June 2008). "Levetiracetam in the treatment of epilepsy". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 4 (3): 507–23. doi:10.2147/NDT.S2937. PMC 2526377. PMID 18830435.

- ^ a b c "DailyMed - KEPPRA- levetiracetam tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ a b c d "Levetiracetam Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Branch Website Management. "Patent Terms Extended Under 35 USC §156". www.uspto.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ^ a b Mbizvo, Gashirai K; Dixon, Pete; Hutton, Jane L; Marson, Anthony G (2012). "Levetiracetam add-on for drug-resistant focal epilepsy: An updated Cochrane Review". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD001901. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001901.pub2. PMID 22972056.

- ^ Webber, Keith (September 12, 2011). "FDA Access Data" (PDF). ANDA 091291. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ BNF 59. BMA & RPSGB. 2010.

- ^ Khan NR, VanLandingham MA, Fierst TM, Hymel C, Hoes K, Evans LT, Mayer R, Barker F, Klimo P (December 2016). "Should Levetiracetam or Phenytoin Be Used for Posttraumatic Seizure Prophylaxis? A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-analysis". Neurosurgery. 79 (6): 775–782. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000001445. PMID 27749510.

- ^ Brophy, Gretchen M.; Bell, Rodney; Claassen, Jan; Alldredge, Brian; Bleck, Thomas P.; Glauser, Tracy; Laroche, Suzette M.; Riviello, James J.; Shutter, Lori; Sperling, Michael R.; Treiman, David M.; Vespa, Paul M.; Neurocritical Care Society Status Epilepticus Guideline Writing Committee (2012). "Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Status Epilepticus". Neurocritical Care. 17 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z. PMID 22528274.

- ^ Meierkord, H.; Boon, P.; Engelsen, B.; Göcke, K.; Shorvon, S.; Tinuper, P.; Holtkamp, M. (2010). "EFNS guideline on the management of status epilepticus in adults". European Journal of Neurology. 17 (3): 348–55. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02917.x. PMID 20050893.

- ^ Shah, Dharmen; Husain, Aatif M. (2009). "Utility of levetiracetam in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage". Seizure. 18 (10): 676–9. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2009.09.003. PMID 19864168.

- ^ Martínez-Granero, M. A.; García-Pérez, A; Montañes, F (2010). "Levetiracetam as an alternative therapy for Tourette syndrome". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 6: 309–16. PMC 2898169. PMID 20628631.

- ^ a b Farooq MU, Bhatt A, Majid A, Gupta R, Khasnis A, Kassab MY (2009). "Levetiracetam for managing neurologic and psychiatric disorders". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 66 (6): 541–61. doi:10.2146/ajhp070607. PMID 19265183.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Sanchez, P. E.; Zhu, L.; Verret, L.; Vossel, K. A.; Orr, A. G.; Cirrito, J. R.; Devidze, N.; Ho, K.; Yu, G.-Q.; Palop, J. J.; Mucke, L. (2012). "Levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (42): E2895–903. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E2895S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121081109. PMC 3479491. PMID 22869752.

- ^ Crawford-Faucher, A; Huijon, R. M. (2015). "The Role of Levetiracetam in Treating Chronic Neuropathic Pain Symptoms". American Family Physician. 92 (1): 23–4. PMID 26132123.

- ^ Zesiewicz, T. A.; Elble, R. J.; Louis, E. D.; Gronseth, G. S.; Ondo, W. G.; Dewey, R. B.; Okun, M. S.; Sullivan, K. L.; Weiner, W. J. (2011). "Evidence-based guideline update: Treatment of essential tremor: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 77 (19): 1752–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd. PMC 3208950. PMID 22013182.

- ^ Volkmar, Fred; Siegel, Matthew; Woodbury-Smith, Marc; King, Bryan; McCracken, James; State, Matthew (2014). "Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 53 (2): 237–57. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.013. PMID 24472258.

- ^ Hirota, Tomoya; Veenstra-Vanderweele, Jeremy; Hollander, Eric; Kishi, Taro (2013). "Antiepileptic Medications in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 44 (4): 948–57. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1952-2. PMID 24077782.

- ^ Frye, Richard; Rossignol, Daniel; Casanova, Manuel F.; Brown, Gregory L.; Martin, Victoria; Edelson, Stephen; Coben, Robert; Lewine, Jeffrey; Slattery, John C. (2013). "A review of traditional and novel treatments for seizures in autism spectrum disorder: Findings from a systematic review and expert panel". Frontiers in Public Health. 1: 31. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00031. PMC 3859980. PMID 24350200.

- ^ "Advancements in the Treatment of Epilepsy" (PDF). harvard.edu. 1 January 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Keppra (levetiracetam) Prescribing Information" (PDF).

- ^ Gambardella, Antonio (2008). "Monotherapy for partial epilepsy: Focus on levetiracetam". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 4 (1): 33–8. doi:10.2147/NDT.S1655. PMC 2515905. PMID 18728811.

- ^ Zou, Li-Ping; Ding, Chang-Hong; Song, Zhen-Jiang; Li, Xiao-Feng (2012). "Stevens–Johnson syndrome induced by levetiracetam". Seizure. 21 (10): 823–5. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.09.005. PMID 23036769.

- ^ Griebel, May L. (1998). "Acute Management of Hypersensitivity Reactions and Seizures". Epilepsia. 39: S17–21. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01680.x. PMID 9798757.

- ^ Beniczky, Simona Alexandra; Viken, Janina; Jensen, Lars Thorbjørn; Andersen, Noémi Becser (2012). "Bone mineral density in adult patients treated with various antiepileptic drugs". Seizure. 21 (6): 471–2. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.04.002. PMID 22541979.

- ^ Browne, T. R.; Szabo, G. K.; Leppik, I. E.; Josephs, E.; Paz, J.; Baltes, E.; Jensen, C. M. (2000). "Absence of Pharmacokinetic Drug Interaction of Levetiracetam with Phenytoin in Patients with Epilepsy Determined by New Technique". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 40 (6): 590–5. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.2000.tb05984.x. PMID 10868309.

- ^ Gidal, Barry E.; Baltès, Eugène; Otoul, Christian; Perucca, Emilio (2005). "Effect of levetiracetam on the pharmacokinetics of adjunctive antiepileptic drugs: A pooled analysis of data from randomized clinical trials". Epilepsy Research. 64 (1–2): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.01.005. PMID 15823510.

- ^ Lynch BA, Lambeng N, Nocka K, et al. (June 2004). "The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101 (26): 9861–6. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9861L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308208101. PMC 470764. PMID 15210974.

- ^ Vogl C, Mochida S, Wolff C, et al. (August 2012). "The Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A Ligand Levetiracetam Inhibits Presynaptic Ca2+ Channels through an Intracellular Pathway". Mol. Pharmacol. 82 (2): 199–208. doi:10.1124/mol.111.076687. PMID 22554805.

- ^ Rogawski, MA (June 2006). "Diverse mechanisms of antiepileptic drugs in the development pipeline". Epilepsy Research. 69 (3): 273–94. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.004. PMC 1562526. PMID 16621450.

- ^ "Levetiracetam Injection Prescribing Information" (PDF).

- ^ "Products | UCB". www.ucb-usa.com. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ^ "FDA approves the first 3D-printed drug product | KurzweilAI". www.kurzweilai.net. October 13, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

External links[edit]

- PubMed Health A division of the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health.

- Keppra (levetiracetam) Final Printed Label April 2009. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed 29 July 2011.

- Keppra UCB (manufacturer's website)

- NIH MedLine drug information