Paracetamol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Paracetamol: /ˌpærəˈsiːtəmɒl/ Acetaminophen: /əˌsiːtəˈmɪnəfɪn/ ( |

| Trade names | Tylenol, Panadol, others[2] |

| Synonyms | N-acetyl-para-aminophenol (APAP), acetaminophen (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681004 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, through the cheek, rectal, intravenous (IV) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 63–89%[4]:73 |

| Protein binding | 10–25%[5] |

| Metabolism | Predominantly in the liver[3] |

| Metabolites | APAP gluc, APAP sulfate, APAP GSH, APAP cys, NAPQI[6] |

| Onset of action | Pain relief onset by route: By mouth – 37 minutes[7] Buccal – 15 minutes[7] Intravenous – 8 minutes[7] |

| Elimination half-life | 1–4 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Urine (85–90%)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.870 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H9NO2 |

| Molar mass | 151.163 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.263 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 169 °C (336 °F) [9][10] |

| Boiling point | 420 °C (788 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 7.21 g/kg (0 °C)[8] 8.21 g/kg (5°C)[8] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen and APAP, is a medicine used to treat pain and fever.[1] It is typically used for mild to moderate pain relief.[1] Evidence for its use to relieve fever in children is mixed.[11][12] It is often sold in combination with other medications, such as in many cold medications.[1] In combination with opioid pain medication, paracetamol is also used for severe pain such as cancer pain and pain after surgery.[13] It is typically used either by mouth or rectally, but is also available intravenously.[1][14] Effects last between 2 and 4 hours.[14]

Paracetamol is generally safe at recommended doses.[15] The recommended maximum daily dose for an adult is 3 or 4 grams.[16][17] Higher doses may lead to toxicity, including liver failure.[1] Serious skin rashes may rarely occur.[1] It appears to be safe during pregnancy and when breastfeeding.[1] In those with liver disease, it may still be used, but in lower doses.[18] It is classified as a mild analgesic.[14] It does not have significant anti-inflammatory activity and how it works is not entirely clear.[19]

Paracetamol was first made in 1877.[20] It is the most commonly used medication for pain and fever in both the United States and Europe.[21] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[22] Paracetamol is available as a generic medication with trade names including Tylenol and Panadol, among others.[23] The wholesale price in the developing world is less than US$ 0.01 per dose.[24] In the United States, it costs about US$0.04 per dose.[25]

Medical uses[edit]

Fever[edit]

Paracetamol is used for reducing fever in people of all ages.[26] The World Health Organization recommends that paracetamol be used to treat fever in children only if their temperature is higher than 38.5 °C (101.3 °F).[27] The efficacy of paracetamol by itself in children with fevers has been questioned[28] and a meta-analysis showed that it is less effective than ibuprofen.[29] Paracetamol does not have significant anti-inflammatory effects.

Pain[edit]

Paracetamol is used for the relief of mild to moderate pain.[1] The use of the intravenous form for short-term pain in people in the emergency department is supported by limited evidence.[30]

Osteoarthritis[edit]

The American College of Rheumatology recommends paracetamol as one of several treatment options for people with arthritis pain of the hip, hand, or knee that does not improve with exercise and weight loss.[31] A 2015 review, however, found it provided only a small benefit in osteoarthritis.[32]

Paracetamol has relatively little anti-inflammatory activity, unlike other common analgesics such as the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) aspirin, and ibuprofen, but ibuprofen and paracetamol have similar effects in the treatment of headache. Paracetamol can relieve pain in mild arthritis, but has no effect on the underlying inflammation, redness, and swelling of the joint.[33] It has analgesic properties comparable to those of aspirin, while its anti-inflammatory effects are weaker. It is better tolerated than aspirin due to concerns about bleeding with aspirin.

Low back[edit]

Based on a systematic review, paracetamol is recommended by the American Pain Society as a first-line treatment for low back pain.[34] In contrast, the American College of Physicians found good evidence for NSAIDs but only fair evidence for paracetamol, while other systematic reviews have concluded that evidence for its efficacy is lacking entirely.[32][35][36][37]

Headaches[edit]

A joint statement of the German, Austrian, and Swiss headache societies and the German Society of Neurology recommends the use of paracetamol in combination with caffeine as one of several first-line therapies for treatment of tension or migraine headache.[38] In the treatment of acute migraine, it is superior to placebo, with 39% of people experiencing pain relief at 1 hour compared with 20% in the control group.[39]

Postoperative[edit]

Paracetamol combined with NSAIDs may be more effective for treating postoperative pain than either paracetamol or NSAIDs alone.[40]

Teeth[edit]

NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac are more effective than paracetamol for controlling dental pain or pain arising from dental procedures; combinations of NSAIDs and paracetamol are more effective than either alone.[41] Paracetamol is particularly useful when NSAIDs are contraindicated due to hypersensitivity or history of gastrointestinal ulceration or bleeding.[42] It can also be used in combination with NSAIDs when these are ineffective in controlling dental pain alone.[43] The Cochrane review of preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents shows no evidence of benefit in taking paracetamol before dental treatment to help reduce pain after treatment for procedures under local anaesthetic, but the quality of evidence is low.[44]

Other[edit]

The efficacy of paracetamol when used in combination with weak opioids (such as codeine) improved for about 50% of people, but with increases in the number experiencing side effects.[45][46] Combination drugs of paracetamol and strong opioids such as morphine improve analgesic effect.[47]

The combination of paracetamol with caffeine is superior to paracetamol alone for the treatment of common pain conditions, including dental pain, post partum pain, and headache.[48]

Patent ductus arteriosus[edit]

Paracetamol is used to treat patent ductus arteriosus, a condition that affects newborns when a blood vessel used in developing the lungs fails to close as it normally does, but evidence for the safety and efficacy of paracetamol for this purpose is lacking.[49][50] NSAIDs, particularly indomethacin and ibuprofen, have also been used, but the evidence for them is also not strong.[49] The condition appears to be caused in part by overactive prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), signalling primarily through its EP4 receptor, but possibly also through its EP2 receptor and EP3 receptors.[49]

Adverse effects[edit]

Healthy adults taking regular doses up to 4,000 mg a day shows little evidence of toxicity (although some researchers disagree[according to whom?]). They are more likely to have abnormal liver function tests, but the importance of this is uncertain.[32]

Liver damage[edit]

Acute overdoses of paracetamol can cause potentially fatal liver damage. In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration launched a public-education program to help consumers avoid overdose, warning: "Acetaminophen can cause serious liver damage if more than directed is used."[51][52][53] In a 2011 Safety Warning, the FDA immediately required manufacturers to update labels of all prescription combination acetaminophen products to warn of the potential risk for severe liver injury and required that such combinations contain no more than 325 mg of acetaminophen.[54][55] Overdoses are frequently related to high-dose recreational use of prescription opioids, as these opioids are most often combined with acetaminophen.[56] The overdose risk may be heightened by frequent consumption of alcohol.

Paracetamol toxicity is the foremost cause of acute liver failure in the Western world, and accounts for most drug overdoses in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[57][58][59][60] According to the FDA, in the United States, "56,000 emergency room visits, 26,000 hospitalizations, and 458 deaths per year [were] related to acetaminophen-associated overdoses during the 1990s. Within these estimates, unintentional acetaminophen overdose accounted for nearly 25% of the emergency department visits, 10% of the hospitalizations, and 25% of the deaths."[61]

Paracetamol is metabolised by the liver and is hepatotoxic; side effects are multiplied when combined with alcoholic drinks, and are very likely in chronic alcoholics or people with liver damage.[62][63] Some studies have suggested the possibility of a moderately increased risk of upper gastrointestinal complications such as stomach bleeding when high doses are taken chronically.[64] Kidney damage is seen in rare cases, most commonly in overdose.[65]

Skin reactions[edit]

On August 2, 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a new warning about paracetamol. It stated that the drug could cause rare and possibly fatal skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Prescription-strength products will be required to carry a warning label about skin reactions, and the FDA has urged manufacturers to do the same with over-the-counter products.[66]

Asthma[edit]

An association exists between paracetamol use and asthma, but whether this association is causal is still debated as of 2017.[67] Certain evidence suggests that this association likely reflects confounders[68] rather than being truly causal.[69] A 2014 review found that among children, the association disappeared when respiratory infections were taken into account.[70]

As of 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence continue to recommend paracetamol for pain and discomfort in children,[71][72][73][74][75][76] but some experts have recommended that paracetamol use by children with asthma or at risk for asthma should be avoided.[77][78]

Other factors[edit]

In contrast to aspirin, paracetamol does not prevent blood from clotting (it is not an antiplatelet), thus may be used in people who have concerns with blood coagulation. Additionally it does not cause gastric irritation.[79] However, paracetamol does not help reduce inflammation, while aspirin does.[80] Compared with ibuprofen—whose side effects may include diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain—paracetamol has fewer adverse gastrointestinal effects.[81] Unlike aspirin, paracetamol is generally considered safe for children, as it is not associated with a risk of Reye's syndrome in children with viral illnesses.[82] If taken recreationally with opioids, weak evidence suggests that it may cause hearing loss.[83]

Overdose[edit]

In general the recommended maximum daily dose of paracetamol for healthy adults is 3 or 4 grams.[16][17] Higher doses may lead to toxicity.

Untreated paracetamol overdose results in a lengthy, painful illness. Signs and symptoms of paracetamol toxicity may initially be absent or non-specific symptoms. The first symptoms of overdose usually begin several hours after ingestion, with nausea, vomiting, sweating, and pain as acute liver failure starts.[84] People who take overdoses of paracetamol do not fall asleep or lose consciousness, although most people who attempt suicide with paracetamol wrongly believe that they will be rendered unconscious by the drug.[85] The process of dying from an overdose takes from 3–5 days to 4–6 weeks.

Paracetamol hepatotoxicity is by far the most common cause of acute liver failure in both the United States and the United Kingdom.[60][86] Paracetamol overdose results in more calls to poison control centers in the US than overdose of any other pharmacological substance.[87] Toxicity of paracetamol is believed to be due to its quinone metabolite.[88]

Untreated overdose can lead to liver failure and death within days. Treatment is aimed at removing the paracetamol from the body and replenishing glutathione.[88] Activated charcoal can be used to decrease absorption of paracetamol if the person comes to the hospital soon after the overdose. While the antidote, acetylcysteine (also called N-acetylcysteine or NAC), acts as a precursor for glutathione, helping the body regenerate enough to prevent or at least decrease the possible damage to the liver; a liver transplant is often required if damage to the liver becomes severe.[57][89] NAC was usually given following a treatment nomogram (one for people with risk factors, and one for those without), but the use of the nomogram is no longer recommended as evidence to support the use of risk factors was poor and inconsistent, and many of the risk factors are imprecise and difficult to determine with sufficient certainty in clinical practice.[90] NAC also helps in neutralizing the imidoquinone metabolite of paracetamol.[88] Kidney failure is also a possible side effect.

Until 2004, tablets were available in the UK (brand-name Paradote) that combined paracetamol with an antidote (methionine) to protect the liver in case of an overdose. One theoretical, but rarely if ever used, option in the United States is to request a compounding pharmacy to make a similar drug mix for people who are at risk.

In June 2009, an FDA advisory committee recommended that new restrictions be placed on paracetamol use in the United States to help protect people from the potential toxic effects. The maximum dosage at any given time would be decreased from 1000 mg to 650 mg, while combinations of paracetamol and opioid analgesics would be prohibited. Committee members were particularly concerned by the fact that the then-present maximum dosages of paracetamol had been shown to produce alterations in hepatic function.[91]

In January 2011, the FDA asked manufacturers of prescription combination products containing paracetamol to limit its amount to no more than 325 mg per tablet or capsule and began requiring manufacturers to update the labels of all prescription combination paracetamol products to warn of the potential risk of severe liver damage.[92][93][94][95] Manufacturers had three years to limit the amount of paracetamol in their prescription drug products to 325 mg per dosage unit.[93][95] In November 2011, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency revised UK dosing of liquid paracetamol for children.[96]

Pregnancy[edit]

Experimental studies in animals and cohort studies in humans indicate no detectable increase in congenital malformations associated with paracetamol use during pregnancy.[97] Additionally, paracetamol does not affect the closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus as NSAIDs can.[98]

Paracetamol use by the mother during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma.[99] It is also associated with an increase in ADHD but it is unclear whether the relationship is causal.[100] A 2015 review states that paracetamol remains a first-line recommended medication for pain and fever during pregnancy, despite these concerns.[101]

Cancer[edit]

Some studies have found an association between paracetamol and a slight increase in kidney cancer,[102] but no effect on bladder cancer risk.[103]

Interactions[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

Pharmacology[edit]

Mechanism of action[edit]

The mechanism of action of paracetamol is not completely understood. Unlike NSAIDs such as aspirin, paracetamol does not appear to inhibit the function of any cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme outside the central nervous system, and this appears to be the reason why it is not useful as an anti-inflammatory.[104] It does appear to selectively inhibit COX activities in the brain, which may contribute to its ability to treat fever and pain.[104] This activity does not appear to be direct inhibition by blocking an active site, but rather by reducing COX, which must be oxidized in order to function.[104]

Paracetamol apparently might modulate the endogenous cannabinoid system in the brain through its metabolite, AM404, which appears to inhibit the reuptake of the endogenous cannabinoid/vanilloid anandamide by neurons, making it more available to reduce pain. AM404 also appears to be able to directly activate the TRPV1 (older name: vanilloid receptor), which also inhibits pain signals in the brain.[104]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

After being taken by mouth, it is rapidly absorbed by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (although absorption through the stomach is negligible);[105] its volume of distribution is roughly 50 L.[106] The concentration in serum after a typical dose of paracetamol usually peaks below 30 µg/ml (200 µmol/L).[107] After 4 hours, the concentration is usually less than 10 µg/ml (66 µmol/L).[107]

Paracetamol is metabolised primarily in the liver, into toxic and nontoxic products. Three metabolic pathways are notable:[88]

- Glucuronidation (45-55%),[3] by UGT1A1 and UGT1A6;[103]

- Sulfation (sulfate conjugation) (20–30%)[3] by SULT1A1;[103]

- N-hydroxylation and dehydration, then glutathione conjugation, (less than 15%). The hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme system metabolises paracetamol (mainly CYP2E1), forming a minor yet significant alkylating metabolite known as NAPQI (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine) (also known as N-acetylimidoquinone).[88][108] NAPQI is then irreversibly conjugated with the sulfhydryl groups of glutathione.[108]

All three pathways yield final products that are inactive, nontoxic, and eventually excreted by the kidneys. In the third pathway, however, the intermediate product NAPQI is toxic. NAPQI is primarily responsible for the toxic effects of paracetamol; this constitutes an example of toxication.[109] Production of NAPQI is due primarily to two isoenzymes of cytochrome P450: CYP2E1[103] and CYP3A4.[109] At usual doses, NAPQI is quickly detoxified by conjugation with glutathione.[88][108]

Chemistry[edit]

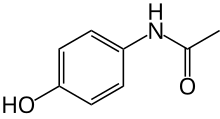

Chemical properties[edit]

Paracetamol consists of a benzene ring core, substituted by one hydroxyl group and the nitrogen atom of an amide group in the para (1,4) pattern.[110] The amide group is acetamide (ethanamide). It is an extensively conjugated system, as the lone pair on the hydroxyl oxygen, the benzene pi cloud, the nitrogen lone pair, the p orbital on the carbonyl carbon, and the lone pair on the carbonyl oxygen are all conjugated. The presence of two activating groups also make the benzene ring highly reactive toward electrophilic aromatic substitution. As the substituents are ortho, para-directing and para with respect to each other, all positions on the ring are more or less equally activated. The conjugation also greatly reduces the basicity of the oxygens and the nitrogen, while making the hydroxyl acidic through delocalisation of charge developed on the phenoxide anion.

Paracetamol is part of the class of drugs known as "aniline analgesics"; it is the only such drug still in use today.[111] It is not considered an NSAID because it does not exhibit significant anti-inflammatory activity (it is a weak COX inhibitor).[112][113] This is despite the evidence that paracetamol and NSAIDs have some similar pharmacological activity.[114]

Synthesis[edit]

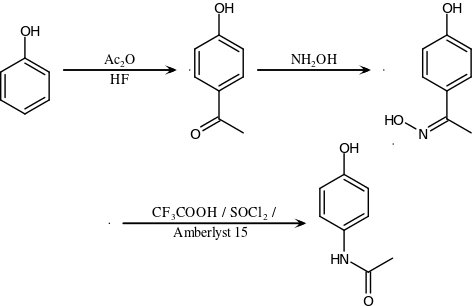

Original (Boots) method[edit]

The original method for production involves the nitration of phenol with sodium nitrate gives a mixture of two isomers, from which the wanted 4-nitrophenol (bp 279 °C) can easily be separated by steam distillation. In this electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction, phenol's oxygen is strongly activating, thus the reaction requires only mild conditions as compared to nitration of benzene itself. The nitro group is then reduced to an amine, giving 4-aminophenol. Finally, the amine is acetylated with acetic anhydride.[115] Industrially direct hydrogenation is used, but in the laboratory scale sodium borohydride serves.[116][117]

Green synthesis[edit]

An alternative industrial synthesis developed by Hoechst–Celanese involves direct acylation of phenol with acetic anhydride catalyzed by HF, conversion of the ketone to a ketoxime with hydroxylamine, followed by the acid-catalyzed Beckmann rearrangement to give the amide.[117][118]

Direct synthesis[edit]

More recently (2014) a "one-pot" synthesis from hydroquinone has been described before the Royal Society of Chemistry.[119][120] The process may be summarized as follows:

- Hydroquinone, ammonium acetate, and acetic acid were mixed in an argon atmosphere and heated slowly to 230 °C. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 15 hours. After cooling the acetic acid was evaporated and the precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried to give paracetamol as a white solid.

The authors go on to claim an 88% yield and 99% purity.

Reactions[edit]

4-Aminophenol may be obtained by the amide hydrolysis of paracetamol. 4-Aminophenol prepared this way, and related to the commercially available Metol, has been used as a developer in photography by hobbyists.[121] This reaction is also used to determine paracetamol in urine samples: After hydrolysis with hydrochloric acid, 4-aminophenol reacts in ammonia solution with a phenol derivate, e.g. salicylic acid, to form an indophenol dye under oxidization by air.[122]

History[edit]

Acetanilide was the first aniline derivative serendipitously found to possess analgesic as well as antipyretic properties, and was quickly introduced into medical practice under the name of Antifebrin by A. Cahn and P. Hepp in 1886.[123] But its unacceptable toxic effects, the most alarming being cyanosis due to methemoglobinemia, prompted the search for less toxic aniline derivatives.[111] Harmon Northrop Morse had already synthesized paracetamol at Johns Hopkins University via the reduction of p-nitrophenol with tin in glacial acetic acid in 1877,[124][125] but it was not until 1887 that clinical pharmacologist Joseph von Mering tried paracetamol on humans.[111] In 1893, von Mering published a paper reporting on the clinical results of paracetamol with phenacetin, another aniline derivative.[126] Von Mering claimed that, unlike phenacetin, paracetamol had a slight tendency to produce methemoglobinemia. Paracetamol was then quickly discarded in favor of phenacetin. The sales of phenacetin established Bayer as a leading pharmaceutical company.[127] Overshadowed in part by aspirin, introduced into medicine by Heinrich Dreser in 1899, phenacetin was popular for many decades, particularly in widely advertised over-the-counter "headache mixtures", usually containing phenacetin, an aminopyrine derivative of aspirin, caffeine, and sometimes a barbiturate.[111]

Paracetamol is the active metabolite of phenacetin and acetanilide, both once popular as analgesics and antipyretics in their own right.[106][128] However, unlike phenacetin, acetanilide and their combinations, paracetamol is not considered carcinogenic at therapeutic doses.[129]

Von Mering's claims remained essentially unchallenged for half a century, until two teams of researchers from the United States analyzed the metabolism of acetanilide and paracetamol.[127] In 1947 David Lester and Leon Greenberg found strong evidence that paracetamol was a major metabolite of acetanilide in human blood, and in a subsequent study they reported that large doses of paracetamol given to albino rats did not cause methemoglobinemia.[130] In three papers published in the September 1948 issue of the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Bernard Brodie, Julius Axelrod and Frederick Flinn confirmed using more specific methods that paracetamol was the major metabolite of acetanilide in human blood, and established that it was just as efficacious an analgesic as its precursor.[131][132][133] They also suggested that methemoglobinemia is produced in humans mainly by another metabolite, phenylhydroxylamine. A follow-up paper by Brodie and Axelrod in 1949 established that phenacetin was also metabolised to paracetamol.[134] This led to a "rediscovery" of paracetamol.[111] It has been suggested that contamination of paracetamol with 4-aminophenol, the substance von Mering synthesised it from, may be the cause for his spurious findings.[127]

Paracetamol was first marketed in the United States in 1950 under the name Triagesic, a combination of paracetamol, aspirin, and caffeine.[125] Reports in 1951 of three users stricken with the blood disease agranulocytosis led to its removal from the marketplace, and it took several years until it became clear that the disease was unconnected.[125] Paracetamol was marketed in 1953 by Sterling-Winthrop Co. as Panadol, available only by prescription, and promoted as preferable to aspirin since it was safe for children and people with ulcers.[125][127][135] In 1955, paracetamol was marketed as Children's Tylenol Elixir by McNeil Laboratories.[136] In 1956, 500 mg tablets of paracetamol went on sale in the United Kingdom under the trade name Panadol, produced by Frederick Stearns & Co, a subsidiary of Sterling Drug Inc. In 1963, paracetamol was added to the British Pharmacopoeia, and has gained popularity since then as an analgesic agent with few side-effects and little interaction with other pharmaceutical agents.[125] Concerns about paracetamol's safety delayed its widespread acceptance until the 1970s, but in the 1980s paracetamol sales exceeded those of aspirin in many countries, including the United Kingdom. This was accompanied by the commercial demise of phenacetin, blamed as the cause of analgesic nephropathy and hematological toxicity.[111] In 1988 Sterling Winthrop was acquired by Eastman Kodak which sold the over the counter drug rights to SmithKline Beecham in 1994.[137]

Available without a prescription since 1959,[138] it has since become a common household drug.[139] Patents on paracetamol have long expired, and generic versions of the drug are widely available.[2][140]

Society and culture[edit]

Naming[edit]

Acetaminophen is the name generally used in the United States (USAN), Japan (JAN), Canada[141] Venezuela, Colombia, and Iran; paracetamol is used in international venues (INN, AAN, BAN).[141][142][143] In some contexts, such as on prescription bottles of painkillers that incorporate this medicine, it is simply abbreviated as APAP, for acetyl-para-aminophenol.

Both acetaminophen and paracetamol come from a chemical name for the compound: para-acetylaminophenol and para-acetylaminophenol.

Cost[edit]

The wholesale price in the developing world is less than 0.01 USD per dose.[24] In the United States it costs about US$0.04 per dose.[25]

In the UK, paracetamol is one of the most prescribed drugs by the NHS.[144] In the UK, Paracetamol costs 19p in the supermarket, while the NHS spends 80 m pounds yearly.[145] In Europe, prices differ from country to country; low-cost prices for 10 doses could reach €0.54 in Portugal, €0.91 in France and €1.97 in Germany.[146]

Available forms[edit]

Paracetamol is available in a tablet, capsule, liquid suspension, suppository, intravenous, intramuscular and effervescent forms.[147][148]

In some formulations, paracetamol is combined with the opioid codeine, sometimes referred to as co-codamol (BAN) and Panadeine in Australia. In the U.S., this combination is available only by prescription, while the lowest-strength preparation is over the counter in Canada, and in other countries other strengths may be available over the counter.[citation needed] Paracetamol is also combined with other opioids such as dihydrocodeine, referred to as co-dydramol (BAN), oxycodone or hydrocodone. Another very commonly used analgesic combination includes paracetamol in combination with propoxyphene napsylate. A combination of paracetamol, codeine, and the calmative doxylamine succinate is also available. The efficacy of paracetamol/codeine combinations has been questioned by recent research.[47]

Paracetamol is commonly used in multi-ingredient preparations for migraine headache, typically including butalbital and paracetamol with or without caffeine, and sometimes containing codeine.

Paracetamol is sometimes combined with phenylephrine hydrochloride.[149] Sometimes a third active ingredient, such as ascorbic acid,[149][150] caffeine,[151][152] chlorpheniramine maleate,[153] or guaifenesin[154][155][156] is added to this combination.

When marketed in combination with diphenhydramine hydrochloride, it is frequently given the label "PM" and is meant as a sleep aid. Diphenhydramine hydrochloride is known to have hypnotic effects and is non-habit forming. Unfortunately it has been implicated in the occasional development of restless leg syndrome.[157]

Controversy[edit]

In September 2013, an episode of This American Life titled "Use Only as Directed"[158] highlighted deaths from paracetamol overdose. This report was followed by two reports by ProPublica[159][160] alleging that the "FDA has long been aware of studies showing the risks of acetaminophen. So has the maker of Tylenol, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a division of Johnson & Johnson" and "McNeil, the maker of Tylenol, ... has repeatedly opposed safety warnings, dosage restrictions and other measures meant to safeguard users of the drug."

A report prepared by an internal FDA working group describes a history of FDA initiatives designed to educate consumers about the risk of paracetamol overdose and notes that one challenge to the Agency has been "identifying the appropriate message about the relative safety of acetaminophen, especially compared to other OTC pain relievers (e.g., aspirin and other NSAIDs)". The report notes that "Chronic use of NSAIDs is also associated with significant morbidity and mortality. NSAID gastrointestinal risk is substantial, with deaths and hospitalization estimated in one publication as 3200 and 32,000 per year respectively. Possible cardiovascular toxicity with chronic NSAID use has been a major discussion recently", finally noting that "The goal of the educational efforts is not to decrease appropriate acetaminophen use or encourage substitution of NSAID use, but rather to educate consumers so that they can avoid unnecessary health risks."[161]

Veterinary use[edit]

Cats[edit]

Paracetamol is extremely toxic to cats, which lack the necessary UGT1 enzyme to break it down safely. Initial symptoms include vomiting, salivation, and discoloration of the tongue and gums.

Unlike an overdose in humans, liver damage is rarely the cause of death; instead, methemoglobin formation and the production of Heinz bodies in red blood cells inhibit oxygen transport by the blood, causing asphyxiation (methemoglobemia and hemolytic anemia).[162]

Treatment with N-acetylcysteine,[163] methylene blue or both is sometimes effective after the ingestion of small doses of paracetamol.

Dogs[edit]

Although paracetamol is believed to have no significant anti-inflammatory activity, it has been reported to be as effective as aspirin in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain in dogs.[164]

A paracetamol-codeine product (trade name Pardale-V)[165] licensed for use in dogs is available for purchase under supervision of a vet, pharmacist or other qualified person.[165] It should be administered to dogs only on veterinary advice and with extreme caution.[165]

The main effect of toxicity in dogs is liver damage, and GI ulceration has been reported.[163][166][167][168] N-acetylcysteine treatment is efficacious in dogs when administered within two hours of paracetamol ingestion.[163][164]

Snakes[edit]

Paracetamol is lethal to snakes, and has been suggested as a chemical control program for the invasive brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) in Guam.[169][170] Doses of 80 mg are inserted into dead mice scattered by helicopter.[171]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Acetaminophen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b "International Listings for Paracetamol". Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Codapane Forte Paracetamol and codeine phosphate PRODUCT INFORMATION" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine (2010). Macintyre, PE; Schug, SA; Scott, DA; Visser, EJ; Walker, SM, eds. Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (PDF) (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council. ISBN 9780977517459. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21.

- ^ "Tylenol, Tylenol Infants' Drops (acetaminophen) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Pathway (therapeutic doses), Pharmacokinetics". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Pickering G, Macian N, Libert F, Cardot JM, Coissard S, Perovitch P, Maury M, Dubray C (September 2014). "Buccal acetaminophen provides fast analgesia: two randomized clinical trials in healthy volunteers". Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 8: 1621–1627. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S63476. PMC 4189711. PMID 25302017.

bAPAP has a faster time of antinociception onset (15 minutes, P<0.01) and greater antinociception at 50 minutes (P<0.01, CT1) and 30 minutes (P<0.01, CT2) than ivAPAP and sAPAP. All routes are similar after 50 minutes. ... In postoperative conditions for acute pain of mild to moderate intensity, the quickest reported time to onset of analgesia with APAP is 8 minutes9 for the iv route and 37 minutes6 for the oral route.

- ^ a b c d e Granberg RA, Rasmuson AC (1999). "Solubility of paracetamol in pure solvents". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 44 (6): 1391–95. doi:10.1021/je990124v.

- ^ Karthikeyan, M.; Glen, R. C.; Bender, A. (2005). "General Melting Point Prediction Based on a Diverse Compound Data Set and Artificial Neural Networks". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 45 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1021/ci0500132. PMID 15921448.

- ^ "melting point data for paracetamol". Lxsrv7.oru.edu. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Meremikwu, M; Oyo-Ita, A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMID 12076499.

- ^ De Martino, Maurizio; Chiarugi, Alberto (2015). "Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management". Pain and Therapy. 4 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z. PMC 4676765. PMID 26518691.

- ^ Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2008). "6.1 and 7.1.1" (PDF). Guideline 106: Control of pain in adults with cancer. Scotland: National Health Service (NHS). ISBN 9781905813384. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-20.

- ^ a b c Hochhauser, Daniel (2014). Cancer and its Management. John Wiley & Sons. p. 119. ISBN 9781118468715. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ Russell, FM; Shann, F; Curtis, N; Mulholland, K (2003). "Evidence on the use of paracetamol in febrile children". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81 (5): 367–72. PMC 2572451. PMID 12856055.

- ^ a b "Paracetamol for adults: painkiller to treat aches, pains and fever - NHS.UK". NHS.UK. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ a b "What are the recommended maximum daily dosages of acetaminophen in adults and children?". www.medscape.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Lewis, JH; Stine, JG (June 2013). "Review article: prescribing medications in patients with cirrhosis - a practical guide". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 37 (12): 1132–56. doi:10.1111/apt.12324. PMID 23638982.

- ^ McKay, Gerard A.; Walters, Matthew R. (2013). "Non-Opioid Analgesics". Lecture Notes Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (9th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 9781118344897. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ Mangus, Brent C.; Miller, Michael G. (2005). Pharmacology application in athletic training. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis. p. 39. ISBN 9780803620278.

- ^ Aghababian, Richard V. (22 October 2010). Essentials of emergency medicine. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 814. ISBN 978-1-4496-1846-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Hamilton, Richard J. (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia : 2013 classic shirt-pocket edition (27th ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 12. ISBN 9781449665869. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ a b "Paracetamol". Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Acetaminophen prices, coupons and patient assistance programs". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Baby paracetamol asthma concern". BBC News. September 19, 2008. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMID 12076499.

- ^ Perrott DA, Piira T, Goodenough B, Champion GD (2004). "Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children's pain or fever: a meta-analysis". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 158 (6): 521–6. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.6.521. PMID 15184213.

- ^ Sin, B; Wai, M; Tatunchak, T; Motov, SM (29 January 2016). "The use of intravenous acetaminophen for acute pain in the emergency department". Academic Emergency Medicine. 23 (5): 543–53. doi:10.1111/acem.12921. PMID 26824905.

- ^ Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. (April 2012). "American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee". Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 64 (4): 465–74. doi:10.1002/acr.21596. PMID 22563589.

- ^ a b c Machado, GC; Maher, CG; Ferreira, PH; Pinheiro, MB; Lin, CW; Day, RO; McLachlan, AJ; Ferreira, ML (31 March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 350: h1225. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

- ^ "Paracetamol". Arthritis Research UK. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ "National Guideline Clearinghouse | Expert Commentaries: Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. What's New? What's Different?". Archived from the original on 2014-09-14. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ^ Davies RA, Maher CG, Hancock MJ (November 2008). "A systematic review of paracetamol for non-specific low back pain". Eur Spine J. 17 (11): 1423–30. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0783-x. PMC 2583194. PMID 18797937.

- ^ Saragiotto, BT; Machado, GC; Ferreira, ML; Pinheiro, MB; Abdel Shaheed, C; Maher, CG (June 2016). "Paracetamol for low back pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 6 (6): CD012230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012230. PMID 27271789.

- ^ Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, McLachlan AJ, Ferreira ML (March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials". BMJ. 350: h1225. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

- ^ Haag G, Diener HC, May A, et al. (April 2011). "Self-medication of migraine and tension-type headache: summary of the evidence-based recommendations of the Deutsche Migräne und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN), the Österreichische Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (ÖKSG) and the Schweizerische Kopfwehgesellschaft (SKG)". J Headache Pain. 12 (2): 201–17. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0266-4. PMC 3075399. PMID 21181425.

- ^ Derry S, Moore RA (2013). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3. PMC 4161111. PMID 23633349.

- ^ Ong, CK; Seymour, RA; Lirk, P; Merry, AF (1 April 2010). "Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 110 (4): 1170–9. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cf9281. PMID 20142348.

- ^ Moore, RA; Derry, C (January 2013). "Efficacy of OTC analgesics". International Journal of Clinical Practice. Supplement. 67 (178): 21–5. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12054. PMID 23163544.

- ^ "Relieving dental pain". American Dental Association. December 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17.

- ^ Bailey, E; Worthington, H; Coulthard, P (April 2014). "Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review". British Dental Journal. 216 (8): 451–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.330. PMID 24762895.

- ^ Ashley, PF; Parekh, S; Moles, DR; Anand, P; MacDonald, LC (8 August 2016). "Preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents having dental treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD008392. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008392.pub3. PMID 27501304.

- ^ Anton J M de Craen, Giuseppe Di Giulio, Angela J E M Lampe-Schoenmaeckers, Alphons G H Kessels, Jos Kleijnen (1996). "Analgesic efficacy and safety of paracetamol-codeine combinations versus paracetamol alone: a systematic review". BMJ. 313 (7053): 321–324. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7053.321. PMC 2351742. PMID 8760737.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Laurence Toms; Sheena Derry; R Andrew Moore; Henry J McQuay (2009). "Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001547. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001547.pub2. PMC 4171965. PMID 19160199.

- ^ a b Murnion B (2010). "Combination analgesics in adults". Australian Prescriber (33): 113–5. Archived from the original on 2010-09-02.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (2012). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub2. PMID 22419343.

- ^ a b c Sivanandan S, Agarwal R (2016). "Pharmacological Closure of Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Selecting the Agent and Route of Administration". Paediatric Drugs. 18 (2): 123–38. doi:10.1007/s40272-016-0165-5. PMID 26951240.

- ^ Sallmon H, Koehne P, Hansmann G (2016). "Recent Advances in the Treatment of Preterm Newborn Infants with Patent Ductus Arteriosus". Clinics in Perinatology. 43 (1): 113–29. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2015.11.008. PMID 26876125.

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Page Last Updated: January 16, 2014. Acetaminophen Information Archived 2014-02-16 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed February 23, 2014

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Page updated August 6, 2013 Acetaminophen Toxicity Page accessed February 23, 2014

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration Page updated November 19, 2013 Using Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Safely Archived 2009-07-14 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed February 23, 2014

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 13, 2011 FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings Archived 2011-01-15 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed February 23, 2014

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and. "Drug Safety and Availability - FDA Drug Safety Communication: Prescription Acetaminophen Products to be Limited to 325 mg Per Dosage Unit; Boxed Warning Will Highlight Potential for Severe Liver Failure". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ "FDA: Acetaminophen doses over 325 mg may lead to liver damage". CNN. January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ^ a b Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA (2008). "Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres". Med J Aust. 188 (5): 296–301. PMID 18312195. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23.

- ^ Khashab M, Tector AJ, Kwo PY (2007). "Epidemiology of acute liver failure". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 9 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1007/s11894-008-0023-x. PMID 17335680.

- ^ Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI (2007). "Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature". Drug Saf. 30 (6): 465–79. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730060-00002. PMID 17536874.

- ^ a b Larson AM; Polson J; Fontana RJ; et al. (2005). "Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study". Hepatology. 42 (6): 1364–72. doi:10.1002/hep.20948. PMID 16317692.

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Date Posted Jan 14, 2011. Prescription Drug Products Containing Acetaminophen: Actions to Reduce Liver Injury from Unintentional Overdose Archived 2012-09-25 at WebCite Page accessed February 23, 2014

- ^ Hughes, John (2008). Pain Management: From Basics to Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780443103360.

- ^ Dukes, MNG; Jeffrey K Aronson (2000). Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs, Vol XIV. Elsevier. ISBN 9780444500939.

- ^ García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S (December 15, 2000). "The risk of upper gastrointestinal complications associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, acetaminophen, and combinations of these agents". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 3 (2): 98–101. doi:10.1186/ar146. PMC 128885. PMID 11178116.

- ^ "Painkillers 'cause kidney damage'". BBC News. November 23, 2003. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "FDA Warns of Rare Acetaminophen Risk". August 1, 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ Lourido-Cebreiro, T; Salgado, FJ; Valdes, L; Gonzalez-Barcala, FJ (January 2017). "The association between paracetamol and asthma is still under debate". The Journal of Asthma (Review). 54 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1080/02770903.2016.1194431. PMID 27575940.

- ^ Henderson, AJ; Shaheen, SO (Mar 2013). "Acetaminophen and asthma". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 14 (1): 9–15, quiz 16. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2012.04.004. PMID 23347656.

- ^ Heintze, K; Petersen, KU (Jun 2013). "The case of drug causation of childhood asthma: antibiotics and paracetamol". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 69 (6): 1197–209. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1463-7. PMC 3651816. PMID 23292157.

- ^ Cheelo, M; Lodge, CJ; Dharmage, SC; Simpson, JA; Matheson, M; Heinrich, J; Lowe, AJ (26 November 2014). "Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 100 (1): 81–9. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303043. PMID 25429049.

- ^ "Feverish illness in children: Assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years". NICE clinical guidelines. UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. May 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Common over-the-counter medications". Healthychildren.org. American Academy of Pediatrics. July 10, 2013. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Heintze, K; Petersen, KU (Jun 2013). "The case of drug causation of childhood asthma: antibiotics and paracetamol". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 69 (6): 1197–209. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1463-7. PMC 3651816. PMID 23292157.

- ^ "Link between Calpol and asthma 'not proven'". NHS Choices. UK National Health Service. September 16, 2013. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Section on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Committee on Drugs; Sullivan, JE; Farrar, HC (Mar 2011). "Fever and antipyretic use in children". Pediatrics. 127 (3): 580–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3852. PMID 21357332. Archived from the original on 2015-01-09.

- ^ CHMP Pharmacovigilance Working Party (February 24, 2011). Pharmacovigilance Working Party (PhVWP) February 2011 plenary meeting (PDF) (Report). European Medicines Agency & Heads of Medicines Agencies. pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2013.

- ^ Martinez-Gimeno, A; García-Marcos, Luis (Apr 2013). "The association between acetaminophen and asthma: should its pediatric use be banned?". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 7 (2): 113–22. doi:10.1586/ers.13.8. PMID 23547988. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09.

- ^ McBride, JT (Dec 2011). "The association of acetaminophen and asthma prevalence and severity". Pediatrics. 128 (6): 1181–5. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1106. PMID 22065272. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13.

- ^ Sarg, Michael; Ann D Gross; Roberta Altman (2007). The Cancer Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816064113.

- ^ Neuss, G (2007). Chemistry: Course Companion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-915146-2.

- ^ Ebrahimi, Sedigheh; Soheil Ashkani Esfahani; Hamid Reza Ghaffarian; Mahsima Khoshneviszade (2010). "Comparison of efficacy and safety of acetaminophen and ibuprofen administration as single dose to reduce fever in children". Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 20 (4): 500–501. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- ^ Lesko SM, Mitchell AA (1999). "The safety of acetaminophen and ibuprofen among children younger than two years old". Pediatrics. 104 (4): e39. doi:10.1542/peds.104.4.e39. PMID 10506264.

- ^ Yorgason, JG; Luxford, W; Kalinec, F (Dec 2011). "In vitro and in vivo models of drug ototoxicity: studying the mechanisms of a clinical problem". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 7 (12): 1521–34. doi:10.1517/17425255.2011.614231. PMID 21999330.

- ^ Rumack B, Matthew H (1975). "Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity". Pediatrics. 55 (6): 871–76. PMID 1134886.

- ^ "Paracetamol". University of Oxford Centre for Suicide Research. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Ryder SD, Beckingham IJ (2001). "ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system. Other causes of parenchymal liver disease". BMJ. 322 (7281): 290–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7281.290. PMC 1119531. PMID 11157536.

- ^ Lee WM (2004). "Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: lowering the risks of hepatic failure". Hepatology. 40 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1002/hep.20293. PMID 15239078.

- ^ a b c d e f Mehta, Sweety (August 25, 2012) Metabolism of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen), Acetanilide and Phenacetin Archived 2012-08-30 at the Wayback Machine. pharmaxchange.info

- ^ "Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Acetadote. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ "Paracetamol overdose: new guidance on treatment with intravenous acetylcysteine". Drug Safety Update. 6 (2): A1. September 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-27.

- ^ "FDA May Restrict Acetaminophen". Webmd. 2009-07-01. Archived from the original on 2011-03-21. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ "FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 13, 2011. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Prescription Acetaminophen Products to be Limited to 325 mg Per Dosage Unit; Boxed Warning Will Highlight Potential for Severe Liver Failure". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 13, 2011. Archived from the original on January 18, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Matthew Perrone (January 13, 2011). "FDA orders lowering pain reliever in Vicodin". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Gardiner Harris (January 13, 2011). "F. D. A. Plans New Limits on Prescription Painkillers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ "Liquid paracetamol for children: Revised UK dosing instructions have been introduced". Mhra.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ^ Scialli, AR; Ang, R; Breitmeyer, J; Royal, MA (Dec 2010). "A review of the literature on the effects of acetaminophen on pregnancy outcome" (PDF). Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.). 30 (4): 495–507. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.007. PMID 20659550. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ^ Rudolph, AM (Feb 23, 1981). "Effects of aspirin and acetaminophen in pregnancy and in the newborn". Archives of Internal Medicine. 141 (3): 358–63. doi:10.1001/archinte.141.3.358. PMID 7469626.

- ^ Eyers, S; Weatherall, M; Jefferies, S; Beasley, R (Apr 2011). "Paracetamol in pregnancy and the risk of wheezing in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 41 (4): 482–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03691.x. PMID 21338428. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-14. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ^ Blaser, JA; Allan, GM (July 2014). "Acetaminophen in pregnancy and future risk of ADHD in offspring". Canadian Family Physician. 60 (7): 642. PMC 4096264. PMID 25022638.

- ^ de Fays, L; Van Malderen, K; De Smet, K; Sawchik, J; Verlinden, V; Hamdani, J; Dogné, JM; Dan, B (August 2015). "Use of paracetamol during pregnancy and child neurological development". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 57 (8): 718–24. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12745. PMID 25851072.

- ^ Choueiri, TK.; Je, Y.; Cho, E. (2014). "Analgesic use and the risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies". International Journal of Cancer. 134 (2): 384–396. doi:10.1002/ijc.28093. PMC 3815746. PMID 23400756.

- ^ a b c d Fortuny, J.; Kogevinas, M.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Real, F. X.; Tardòn, A.; Garcia-Closas, R.; Serra, C.; Carrato, A.; Lloreta, J.; Rothman, N.; Villanueva, C.; Dosemeci, M.; Malats, N.; Silverman, D. (2006). "Use of Analgesics and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs, Genetic Predisposition, and Bladder Cancer Risk in Spain". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (9): 1696–1702. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0038. PMID 16985032.

- ^ a b c d Ghanem, CI; Pérez, MJ; Manautou, JE; Mottino, AD (July 2016). "Acetaminophen from liver to brain: New insights into drug pharmacological action and toxicity". Pharmacological Research. 109: 119–31. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.020. PMC 4912877. PMID 26921661.

- ^ Prescott, LF (October 1980). "Kinetics and metabolism of paracetamol and phenacetin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 Suppl 2: 291S–298S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01812.x. PMC 1430174. PMID 7002186.

- ^ a b Graham, GG; Davies, MJ; Day, RO; Mohamudally, A; Scott, KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–32. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833.

- ^ a b John Marx; Ron Walls; Robert Hockberger (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine - Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455749874.

- ^ a b c Borne, Ronald F. "Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs" in Principles of Medicinal Chemistry, Fourth Edition. Eds. Foye, William O.; Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. Published by Williams & Wilkins, 1995. p. 544–545.

- ^ a b Brayfield, A, ed. (15 January 2014). "Paracetamol". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Bales, JR; Nicholson JK; Sadler PJ (1985). "Two-dimensional proton nuclear magnetic resonance "maps" of acetaminophen metabolites in human urine". Clinical Chemistry. 31 (5): 757–762. PMID 3987005. Archived from the original on 2008-11-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: new vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMID 17227290.

- ^ Viswanathan, A. N.; Feskanich, D.; Schernhammer, E. S.; Hankinson, S. E. (2008). "Aspirin, NSAID, and Acetaminophen Use and the Risk of Endometrial Cancer". Cancer Research. 68 (7): 2507–13. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6257. PMC 2857531. PMID 18381460.

- ^ Altinoz, M. A.; Korkmaz, R. (2004). "NF-kappaB, macrophage migration inhibitory factor and cyclooxygenase-inhibitions as likely mechanisms behind the acetaminophen- and NSAID-prevention of the ovarian cancer". Neoplasma. 51 (4): 239–247. PMID 15254653.

- ^ Byrant, Bronwen; Knights, Katleen; Salerno, Evelyn (2007). Pharmacology for health professionals. Elsevier. p. 270. ISBN 9780729537872.

- ^ Ellis, Frank (2002). Paracetamol: a curriculum resource. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-375-0.

- ^ Anthony S. Travis (2007). "Manufacture and uses of the anilines: A vast array of processes and products". In Zvi Rappoport. The chemistry of Anilines Part 1. Wiley. p. 764. ISBN 978-0-470-87171-3.

- ^ a b Elmar Friderichs, Thomas Christoph, Helmut Buschmann, "Analgesics and Antipyretics", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_269.pub2CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ US patent 4524217, Kenneth G. Davenport & Charles B. Hilton, "Process for producing N-acyl-hydroxy aromatic amines", published 1985-06-18, assigned to Celanese Corporation

- ^ Joncour, Roxan; Duguet, Nicolas; Métay, Estelle; Ferreira, Amadéo; Lemaire, Marc (2014). "Amidation of phenol derivatives: a direct synthesis of paracetamol (acetaminophen) from Hydroquinone". Green Chem. 16 (6): 2997–3002. doi:10.1039/C4GC00166D.

- ^ Joncour, Roxan; Duguet, Nicolas; Métay, Estelle; Ferreira, Amadéo; Lemaire, Marc. "Supplementary Information Amidation of phenol derivatives: a direct synthesis of paracetamol (acetaminophen) from hydroquinone" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ Henney, K; Dudley B (1939). Handbook of Photography. Whittlesey House. p. 324.

- ^ Novotny PE, Elser RC (1984). "Indophenol method for acetaminophen in serum examined" (PDF). Clin. Chem. 30 (6): 884–6. PMID 6723045.

- ^ Cahn, A; Hepp P (1886). "Das Antifebrin, ein neues Fiebermittel". Centralbl. Klin. Med. 7: 561–64.

- ^ Morse, H.N. (1878). "Ueber eine neue Darstellungsmethode der Acetylamidophenole" [On a new method of preparing acetylamidophenol]. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 11 (1): 232–3. doi:10.1002/cber.18780110151.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Milton Silverman; Mia Lydecker; Philip Randolph Lee (1992). Bad Medicine: The Prescription Drug Industry in the Third World. Stanford University Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0804716697. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17.

- ^ Von Mering, J (1893). "Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Antipyretica". Ther Monatsch. 7: 577–587.

- ^ a b c d Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 439. ISBN 978-0471899808. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18.

- ^ Toussaint, K; Yang, XC; Zielinski, MA; Reigle, KL; Sacavage, SD; Nagar, S; Raffa, RB (December 2010). "What do we (not) know about how paracetamol (acetaminophen) works?". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 35 (6): 617–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01143.x. PMID 21054454.

- ^ Bergman K, Müller L, Teigen SW (1996). "The genotoxicity and carcinogenicity of paracetamol: a regulatory (re)view". Mutat Res. 349 (2): 263–88. doi:10.1016/0027-5107(95)00185-9. PMID 8600357.

- ^ Lester D, Greenberg LA, Carroll RP (1947). "The metabolic fate of acetanilid and other aniline derivatives: II. Major metabolites of acetanilid appearing in the blood". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 90 (1): 68–75. PMID 20241897. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02.

- ^ Brodie, BB; Axelrod J (1948). "The estimation of acetanilide and its metabolic products, aniline, N-acetyl p-aminophenol and p-aminophenol (free and total conjugated) in biological fluids and tissues". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 22–28. PMID 18885610.

- ^ Brodie, BB; Axelrod J (1948). "The fate of acetanilide in man" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 29–38. PMID 18885611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-07.

- ^ Flinn, Frederick B; Brodie BB (1948). "The effect on the pain threshold of N-acetyl p-aminophenol, a product derived in the body from acetanilide". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 76–77. PMID 18885618.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1949). "The fate of acetophenetidin (phenacetin) in man and methods for the estimation of acetophenitidin and its metabolites in biological material". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 94 (1): 58–67.

- ^ Landau, Ralph; Achilladelis, Basil; Scriabine, Alexander (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-941901-21-5. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17.

- ^ Rapoport, Alan (15 December 1991). Headache Relief. Touchstone. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-671-74803-6. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "SEC Info - Eastman Kodak Co - '8-K' for 6/30/94". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Our Story". McNEIL-PPC, Inc. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "Medication and Drugs". MedicineNet. 1996–2010. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Thakkar, KB; Billa, G (Sep 2013). "The concept of: Generic drugs and patented drugs vs. brand name drugs and non-proprietary (generic) name drugs". Front Pharmacol. 4: 113. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00113. PMC 3770914. PMID 24062686.

- ^ a b Macintyre, Pamela; Rowbotham, David; Walker, Suellen (26 September 2008). Clinical Pain Management Second Edition: Acute Pain. CRC Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-340-94009-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "International Non-Proprietary Name for Pharmaceutical Preparations (Recommended List #4)" (PDF). WHO Chronicle. 16 (3): 101–111. March 1962.

- ^ "TGA Approved Terminology for Medicines, Section 1 – Chemical Substances" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. July 1999: 97. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-11.

- ^ Madden, Hannah; Harris, Jane; Blickem, Christian; Harrison, Rebecca; Timpson, Hannah (2017). ""Always paracetamol, they give them paracetamol for everything": A qualitative study examining Eastern European migrants' experiences of the UK health service". BMC Health Services Research. 17 (1): 604. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2526-3. PMC 5575835. PMID 28851364.

- ^ The Secret Doctor (2015-08-25). "People would use the NHS less if they knew the true price tags". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ^ "Les prix en Europe - La boîte paracétamol 10 comprimés (générique)" (in French). Linternaute.com. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ^ "Acetaminophen." Physicians' Desk Reference, 63rd ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR; 2009: 1915–1916.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Overdose and Liver Injury — Background and Options for Reducing Injury" (PDF). FDA. May 22, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2014. Background Package for June 29–30, 2009 Meeting of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Committee, Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee and Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee

- ^ a b Atkinson, Hartley C.; Stanescu, Ioana; Anderson, Brian J. (2014). "Increased Phenylephrine Plasma Levels with Administration of Acetaminophen". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1171–1172. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1313942. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 24645960.

- ^ "Ascorbic acid/Phenylephrine/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Phenylephrine/Caffeine/Paracetamol dual relief". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Beechams Decongestant Plus With Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Senyuva, H.; Ozden, T. (2002). "Simultaneous High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Paracetamol, Phenylephrine HCl, and Chlorpheniramine Maleate in Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms" (PDF). Journal of Chromatographic Science. 40 (2): 97–100. doi:10.1093/chromsci/40.2.97. ISSN 0021-9665. PMID 11881712. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-06.

- ^ Janin, A.; Monnet, J. (2014). "Bioavailability of paracetamol, phenylephrine hydrochloride and guaifenesin in a fixed-combination syrup versus an oral reference product". Journal of International Medical Research. 42 (2): 347–359. doi:10.1177/0300060513503762. ISSN 0300-0605. PMID 24553480.

- ^ "Paracetamol – phenylephrine hydrochloride – guaifenesin". NPS MedicineWise. National Prescribing Service (Australia). Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Phenylephrine/Guaifenesin/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Treating a Restless Legs Sydnrome (RLS)". Consumer Reports. 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-12-18.

- ^ "Use Only as Directed". This American Life. Episode 505. Chicago. 20 September 2013. Public Radio International. WBEZ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Gerth, Jeff; T. Christian Miller (20 September 2013). "Use Only as Directed". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Miller, T. Christian; Jeff Gerth (20 September 2013). "Dose of Confusion". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Recommendations for FDA Interventions to Decrease the Occurrence of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ Allen AL (2003). "The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat". Can Vet J. 44 (6): 509–10. PMC 340185. PMID 12839249.

- ^ a b c Richardson, JA (2000). "Management of acetaminophen and ibuprofen toxicoses in dogs and cats" (PDF). J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care. 10 (4): 285–91. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2000.tb00013.x.[dead link]

- ^ a b Maddison, Jill E.; Stephen W. Page; David Church (2002). Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 260–1. ISBN 978-0702025730.

- ^ a b c "Pardale-V Oral Tablets". NOAH Compendium of Data Sheets for Animal Medicines. The National Office of Animal Health (NOAH). 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Villar D, Buck WB, Gonzalez JM (1998). "Ibuprofen, aspirin and acetaminophen toxicosis and treatment in dogs and cats". Vet Hum Toxicol. 40 (3): 156–62. PMID 9610496.

- ^ Meadows, Irina; Gwaltney-Brant, Sharon (2006). "The 10 Most Common Toxicoses in Dogs". Veterinary Medicine: 142–8. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

- ^ Dunayer, E (2004). "Ibuprofen toxicosis in dogs, cats, and ferrets". Veterinary Medicine: 580–6. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

- ^ Johnston J, Savarie P, Primus T, Eisemann J, Hurley J, Kohler D (2002). "Risk assessment of an acetaminophen baiting program for chemical control of brown tree snakes on Guam: evaluation of baits, snake residues, and potential primary and secondary hazards". Environ Sci Technol. 36 (17): 3827–33. doi:10.1021/es015873n. PMID 12322757.

- ^ Brad Lendon (2010-09-07). "Tylenol-loaded mice dropped from air to control snakes". CNN. Archived from the original on 2010-09-09. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ^ Sabrina Richards (2012-05-01). "It's Raining Mice". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paracetamol. |