Connectivity (graph theory)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics and computer science, connectivity is one of the basic concepts of graph theory: it asks for the minimum number of elements (nodes or edges) that need to be removed to separate the remaining nodes into isolated subgraphs.[1] It is closely related to the theory of network flow problems. The connectivity of a graph is an important measure of its resilience as a network.

Contents

Connected graph[edit]

An undirected graph is connected when there is a path between every pair of vertices. In a connected graph, there are no unreachable vertices. A graph that is not connected is disconnected. An undirected graph G is said to be disconnected if there exist two nodes in G such that no path in G has those nodes as endpoints.

A graph with just one vertex is connected. An edgeless graph with two or more vertices is disconnected.

Definitions of components, cuts and connectivity[edit]

In an undirected graph G, two vertices u and v are called connected if G contains a path from u to v. Otherwise, they are called disconnected. If the two vertices are additionally connected by a path of length 1, i.e. by a single edge, the vertices are called adjacent. A graph is said to be connected if every pair of vertices in the graph is connected.

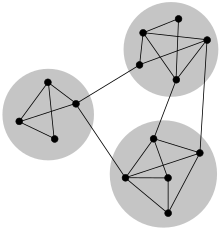

A connected component is a maximal connected subgraph of G. Each vertex belongs to exactly one connected component, as does each edge.

A directed graph is called weakly connected if replacing all of its directed edges with undirected edges produces a connected (undirected) graph. It is connected if it contains a directed path from u to v or a directed path from v to u for every pair of vertices u, v. It is strongly connected, diconnected, or simply strong if it contains a directed path from u to v and a directed path from v to u for every pair of vertices u, v. The strong components are the maximal strongly connected subgraphs.

A cut, vertex cut, or separating set of a connected graph G is a set of vertices whose removal renders G disconnected. The connectivity or vertex connectivity κ(G) (where G is not a complete graph) is the size of a minimal vertex cut. A graph is called k-connected or k-vertex-connected if its vertex connectivity is k or greater.

More precisely, any graph G (complete or not) is said to be k-connected if it contains at least k+1 vertices, but does not contain a set of k − 1 vertices whose removal disconnects the graph; and κ(G) is defined as the largest k such that G is k-connected. In particular, a complete graph with n vertices, denoted Kn, has no vertex cuts at all, but κ(Kn) = n − 1. A vertex cut for two vertices u and v is a set of vertices whose removal from the graph disconnects u and v. The local connectivity κ(u, v) is the size of a smallest vertex cut separating u and v. Local connectivity is symmetric for undirected graphs; that is, κ(u, v) = κ(v, u). Moreover, except for complete graphs, κ(G) equals the minimum of κ(u, v) over all nonadjacent pairs of vertices u, v.

2-connectivity is also called biconnectivity and 3-connectivity is also called triconnectivity. A graph G which is connected but not 2-connected is sometimes called separable.

Analogous concepts can be defined for edges. In the simple case in which cutting a single, specific edge would disconnect the graph, that edge is called a bridge. More generally, an edge cut of G is a set of edges whose removal renders the graph disconnected. The edge-connectivity λ(G) is the size of a smallest edge cut, and the local edge-connectivity λ(u, v) of two vertices u, v is the size of a smallest edge cut disconnecting u from v. Again, local edge-connectivity is symmetric. A graph is called k-edge-connected if its edge connectivity is k or greater.

A graph is said to be maximally connected if its connectivity equals its minimum degree. A graph is said to be maximally edge-connected if its edge-connectivity equals its minimum degree.[2]

Super- and hyper-connectivity[edit]

A graph is said to be super-connected or super-κ if every minimum vertex cut isolates a vertex. A graph is said to be hyper-connected or hyper-κ if the deletion of each minimum vertex cut creates exactly two components, one of which is an isolated vertex. A graph is semi-hyper-connected or semi-hyper-κ if any minimum vertex cut separates the graph into exactly two components.[3]

More precisely: a G connected graph is said to be super-connected or super-κ if all minimum vertex-cuts consist of the vertices adjacent with one (minimum-degree) vertex. A G connected graph is said to be super-edge-connected or super-λ if all minimum edge-cuts consist of the edges incident on some (minimum-degree) vertex.[4]

A cutset X of G is called a non-trivial cutset if X does not contain the neighborhood N(u) of any vertex u ∉ X. Then the superconnectivity κ1 of G is:

- κ1(G) = min{|X| : X is a non-trivial cutset}.

A non-trivial edge-cut and the edge-superconnectivity λ1(G) are defined analogously.[5]

Menger's theorem[edit]

One of the most important facts about connectivity in graphs is Menger's theorem, which characterizes the connectivity and edge-connectivity of a graph in terms of the number of independent paths between vertices.

If u and v are vertices of a graph G, then a collection of paths between u and v is called independent if no two of them share a vertex (other than u and v themselves). Similarly, the collection is edge-independent if no two paths in it share an edge. The number of mutually independent paths between u and v is written as κ′(u, v), and the number of mutually edge-independent paths between u and v is written as λ′(u, v).

Menger's theorem asserts that for distinct vertices u,v, λ(u, v) equals λ′(u, v), and if u is also not adjacent to v then κ(u, v) equals κ′(u, v).[6][7] This fact is actually a special case of the max-flow min-cut theorem.

Computational aspects[edit]

The problem of determining whether two vertices in a graph are connected can be solved efficiently using a search algorithm, such as breadth-first search. More generally, it is easy to determine computationally whether a graph is connected (for example, by using a disjoint-set data structure), or to count the number of connected components. A simple algorithm might be written in pseudo-code as follows:

- Begin at any arbitrary node of the graph, G

- Proceed from that node using either depth-first or breadth-first search, counting all nodes reached.

- Once the graph has been entirely traversed, if the number of nodes counted is equal to the number of nodes of G, the graph is connected; otherwise it is disconnected.

By Menger's theorem, for any two vertices u and v in a connected graph G, the numbers κ(u, v) and λ(u, v) can be determined efficiently using the max-flow min-cut algorithm. The connectivity and edge-connectivity of G can then be computed as the minimum values of κ(u, v) and λ(u, v), respectively.

In computational complexity theory, SL is the class of problems log-space reducible to the problem of determining whether two vertices in a graph are connected, which was proved to be equal to L by Omer Reingold in 2004.[8] Hence, undirected graph connectivity may be solved in O(log n) space.

The problem of computing the probability that a Bernoulli random graph is connected is called network reliability and the problem of computing whether two given vertices are connected the ST-reliability problem. Both of these are #P-hard.[9]

Number of connected graphs[edit]

The number of distinct connected labeled graphs with n nodes is tabulated in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences as sequence A001187, through n = 15. The first few non-trivial terms are

| n | graphs |

|---|---|

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 38 |

| 5 | 728 |

| 6 | 26704 |

| 7 | 1866256 |

| 8 | 251548592 |

Examples[edit]

- The vertex- and edge-connectivities of a disconnected graph are both 0.

- 1-connectedness is equivalent to connectedness for graphs of at least 2 vertices.

- The complete graph on n vertices has edge-connectivity equal to n − 1. Every other simple graph on n vertices has strictly smaller edge-connectivity.

- In a tree, the local edge-connectivity between every pair of vertices is 1.

Bounds on connectivity[edit]

- The vertex-connectivity of a graph is less than or equal to its edge-connectivity. That is, κ(G) ≤ λ(G). Both are less than or equal to the minimum degree of the graph, since deleting all neighbors of a vertex of minimum degree will disconnect that vertex from the rest of the graph.[1]

- For a vertex-transitive graph of degree d, we have: 2(d + 1)/3 ≤ κ(G) ≤ λ(G) = d.[10]

- For a vertex-transitive graph of degree d ≤ 4, or for any (undirected) minimal Cayley graph of degree d, or for any symmetric graph of degree d, both kinds of connectivity are equal: κ(G) = λ(G) = d.[11]

Other properties[edit]

- Connectedness is preserved by graph homomorphisms.

- If G is connected then its line graph L(G) is also connected.

- A graph G is 2-edge-connected if and only if it has an orientation that is strongly connected.

- Balinski's theorem states that the polytopal graph (1-skeleton) of a k-dimensional convex polytope is a k-vertex-connected graph.[12] Steinitz's previous theorem that any 3-vertex-connected planar graph is a polytopal graph (Steinitz theorem) gives a partial converse.

- According to a theorem of G. A. Dirac, if a graph is k-connected for k ≥ 2, then for every set of k vertices in the graph there is a cycle that passes through all the vertices in the set.[13][14] The converse is true when k = 2.

See also[edit]

- Algebraic connectivity

- Cheeger constant (graph theory)

- Dynamic connectivity, Disjoint-set data structure, Partition refinement

- Expander graph

- Graph property

- Scale-free network

- Small-world networks, Six degrees of separation, Small world phenomenon

- Strength of a graph

References[edit]

- ^ a b Diestel, R. (2005). "Graph Theory, Electronic Edition". p. 12.

- ^ Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (2004). Handbook of graph theory. CRC Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-58488-090-5.

- ^ Liu, Qinghai; Zhang, Zhao (2010-03-01). "The existence and upper bound for two types of restricted connectivity". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 158: 516–521. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2009.10.017.

- ^ Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (2004). Handbook of graph theory. CRC Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-58488-090-5.

- ^ Balbuena, Camino; Carmona, Angeles (2001-10-01). "On the connectivity and superconnectivity of bipartite digraphs and graphs". Ars Combinatorica. 61: 3–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.101.1458.

- ^ Gibbons, A. (1985). Algorithmic Graph Theory. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Nagamochi, H.; Ibaraki, T. (2008). Algorithmic Aspects of Graph Connectivity. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Reingold, Omer (2008). "Undirected connectivity in log-space". Journal of the ACM. 55 (4): Article 17, 24 pages. doi:10.1145/1391289.1391291.

- ^ Provan, J. Scott; Ball, Michael O. (1983). "The complexity of counting cuts and of computing the probability that a graph is connected". SIAM Journal on Computing. 12 (4): 777–788. doi:10.1137/0212053. MR 0721012..

- ^ Godsil, C.; Royle, G. (2001). Algebraic Graph Theory. Springer Verlag.

- ^ Babai, L. (1996). Automorphism groups, isomorphism, reconstruction. Technical Report TR-94-10. University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Chapter 27 of The Handbook of Combinatorics.

- ^ Balinski, M. L. (1961). "On the graph structure of convex polyhedra in n-space". Pacific Journal of Mathematics. 11 (2): 431–434. doi:10.2140/pjm.1961.11.431.

- ^ Dirac, Gabriel Andrew (1960). "In abstrakten Graphen vorhandene vollständige 4-Graphen und ihre Unterteilungen". Mathematische Nachrichten. 22: 61–85. doi:10.1002/mana.19600220107. MR 0121311..

- ^ Flandrin, Evelyne; Li, Hao; Marczyk, Antoni; Woźniak, Mariusz (2007). "A generalization of Dirac's theorem on cycles through k vertices in k-connected graphs". Discrete Mathematics. 307 (7–8): 878–884. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2005.11.052. MR 2297171..