Idiom

An idiom (Latin: idiom from Ancient Greek: ἰδίωμα, "special feature, special phrasing, a peculiarity", f. Ancient Greek: ἴδιος, translit. ídios, "one's own") is a phrase or an expression that has a figurative, or sometimes literal, meaning. Categorized as formulaic language, an idiom's figurative meaning is different from the literal meaning.[1] There are thousands of idioms, occurring frequently in all languages. It is estimated that there are at least twenty-five thousand idiomatic expressions in the English language.[2]

Contents

Derivations[edit]

Many idiomatic expressions, in their original use, were not figurative but had literal meaning. Also, sometimes the attribution of a literal meaning can change as the phrase becomes disconnected from its original roots, leading to a folk etymology. For instance, spill the beans (meaning to reveal a secret) has been said to originate from an ancient method of democratic voting, wherein a voter would put a bean into one of several cups to indicate which candidate he wanted to cast his vote for. If the jars were spilled before the counting of votes was complete, anyone would be able to see which jar had more beans, and therefore which candidate was the winner. Over time, the practice was discontinued and the idiom became figurative.

However, this etymology for spill the beans has been questioned by linguists.[3] The earliest known written accounts come from the USA and involve horse racing around 1902–1903, and the one who "spilled the beans" was an unlikely horse who won a race, thus causing the favorites to lose. By 1907 the term was being used in baseball, but the subject who "spilled the beans" shifted to players who made mistakes, allowing the other team to win. By 1908 the term was starting to be applied to politics, in the sense that crossing the floor in a vote was "spilling the beans". However, in all these early usages the term "spill" was used in the sense of "upset" rather than "divulge". A Stack Exchange discussion provided a large number of links to historic newspapers covering the usage of the term from 1902 onwards.[4]

Other idioms are deliberately figurative. Break a leg, used as an ironic way of wishing good luck in a performance or presentation, may have arisen from the belief that one ought not to utter the words "good luck" to an actor. By wishing someone bad luck, it is supposed that the opposite will occur.[5]

Compositionality[edit]

In linguistics, idioms are usually presumed to be figures of speech contradicting the principle of compositionality. That compositionality is the key notion for the analysis of idioms is emphasized in most accounts of idioms.[6][7] This principle states that the meaning of a whole should be constructed from the meanings of the parts that make up the whole. In other words, one should be in a position to understand the whole if one understands the meanings of each of the parts that make up the whole. The following example is widely employed to illustrate the point:

Fred kicked the bucket.

Understood compositionally, Fred has literally kicked an actual, physical bucket. The much more likely idiomatic reading, however, is non-compositional: Fred is understood to have died. Arriving at the idiomatic reading from the literal reading is unlikely for most speakers. What this means is that the idiomatic reading is, rather, stored as a single lexical item that is now largely independent of the literal reading.

In phraseology, idioms are defined as a sub-type of phraseme, the meaning of which is not the regular sum of the meanings of its component parts.[8] John Saeed defines an idiom as collocated words that became affixed to each other until metamorphosing into a fossilised term.[9] This collocation of words redefines each component word in the word-group and becomes an idiomatic expression. Idioms usually do not translate well; in some cases, when an idiom is translated directly word-for-word into another language, either its meaning is changed or it is meaningless.

When two or three words are often used together in a particular sequence, the words are said to be irreversible binomials, or Siamese twins. Usage will prevent the words from being displaced or rearranged. For example, a person may be left "high and dry" but never "dry and high". This idiom in turn means that the person is left in their former condition rather than being assisted so that their condition improves. Not all Siamese twins are idioms, however. "Chips and dip" is an irreversible binomial, but it refers to literal food items, not idiomatic ones.

Mobility[edit]

Idioms possess varying degrees of mobility. While some idioms are used only in a routine form, others can undergo syntactic modifications such as passivization, raising constructions, and clefting, demonstrating separable constituencies within the idiom.[10] Mobile idioms, allowing such movement, maintain their idiomatic meaning where fixed idioms do not:

- Mobile

- I spilled the beans on our project. → The beans were spilled on our project.

- Fixed

- The old man kicked the bucket. → The bucket was kicked (by the old man).

Many fixed idioms lack semantic composition, meaning that the idiom contains the semantic role of a verb, but not of any object. This is true of kick the bucket, which means die. By contrast, the semantically composite idiom spill the beans, meaning reveal a secret, contains both a semantic verb and object, reveal and secret. Semantically composite idioms have a syntactic similarity between their surface and semantic forms.[10]

The types of movement allowed for certain idiom also relate to the degree to which the literal reading of the idiom has a connection to its idiomatic meaning. This is referred to as motivation or transparency. While most idioms that do not display semantic composition generally do not allow non-adjectival modification, those that are also motivated allow lexical substitution.[11] For example, oil the wheels and grease the wheels allow variation for nouns that elicit a similar literal meaning.[12] These types of changes can occur only when speakers can easily recognize a connection between what the idiom is meant to express and its literal meaning, thus an idiom like kick the bucket cannot occur as kick the pot.

From the perspective of dependency grammar, idioms are represented as a catena which cannot be interrupted by non-idiomatic content. Although syntactic modifications introduce disruptions to the idiomatic structure, this continuity is only required for idioms as lexical entries.[13]

Certain idioms, allowing unrestricted syntactic modification, can be said to be metaphors. Expressions such as jump on the bandwagon, pull strings, and draw the line all represent their meaning independently in their verbs and objects, making them compositional. In the idiom jump on the bandwagon, jump on involves joining something and a 'bandwagon' can refer to a collective cause, regardless of context.[10]

Translating idioms[edit]

A literal word-by-word translation of an opaque idiom will most likely not convey the same meaning in other languages. The English idiom kick the bucket has a variety of equivalents in other languages, such as kopnąć w kalendarz ("kick the calendar") in Polish, casser sa pipe ("to break his pipe") in French[14] and tirare le cuoia ("pulling the leathers") in Italian.[15]

Some idioms are transparent.[16] Much of their meaning does get through if they are taken (or translated) literally. For example, lay one's cards on the table meaning to reveal previously unknown intentions, or to reveal a secret. Transparency is a matter of degree; spill the beans (to let secret information become known) and leave no stone unturned (to do everything possible in order to achieve or find something) are not entirely literally interpretable, but only involve a slight metaphorical broadening. Another category of idioms is a word having several meanings, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes discerned from the context of its usage. This is seen in the (mostly uninflected) English language in polysemes, the common use of the same word for an activity, for those engaged in it, for the product used, for the place or time of an activity, and sometimes for a verb.

Idioms tend to confuse those unfamiliar with them; students of a new language must learn its idiomatic expressions as vocabulary. Many natural language words have idiomatic origins, but are assimilated, so losing their figurative senses, for example, in Portuguese, the expression saber de coração 'to know by heart', with the same meaning as in English, was shortened to 'saber de cor', and, later, to the verb decorar, meaning memorize.

In 2015, TED collected 40 examples of bizarre idioms that cannot be translated literally. They include the Swedish saying "to slide in on a shrimp sandwich", which refers to somebody who didn't have to work to get where they are."[17]

Dealing with non-compositionality[edit]

The non-compositionality of meaning of idioms challenges theories of syntax. The fixed words of many idioms do not qualify as constituents in any sense. For example:

How do we get to the bottom of this situation?

The fixed words of this idiom (in bold) do not form a constituent in any theory's analysis of syntactic structure because the object of the preposition (here this situation) is not part of the idiom (but rather it is an argument of the idiom). One can know that it is not part of the idiom because it is variable; for example, How do we get to the bottom of this situation / the claim / the phenomenon / her statement / etc. What this means is that theories of syntax that take the constituent to be the fundamental unit of syntactic analysis are challenged. The manner in which units of meaning are assigned to units of syntax remains unclear. This problem has motivated a tremendous amount of discussion and debate in linguistics circles and it is a primary motivator behind the Construction Grammar framework.[18]

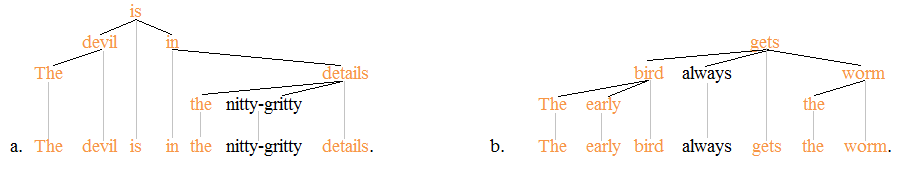

A relatively recent development in the syntactic analysis of idioms departs from a constituent-based account of syntactic structure, preferring instead the catena-based account. The catena unit was introduced to linguistics by William O'Grady in 1998. Any word or any combination of words that are linked together by dependencies qualifies as a catena.[19] The words constituting idioms are stored as catenae in the lexicon, and as such, they are concrete units of syntax. The dependency grammar trees of a few sentences containing non-constituent idioms illustrate the point:

The fixed words of the idiom (in orange) in each case are linked together by dependencies; they form a catena. The material that is outside of the idiom (in normal black script) is not part of the idiom. The following two trees illustrate proverbs:

The fixed words of the proverbs (in orange) again form a catena each time. The adjective nitty-gritty and the adverb always are not part of the respective proverb and their appearance does not interrupt the fixed words of the proverb. A caveat concerning the catena-based analysis of idioms concerns their status in the lexicon. Idioms are lexical items, which means they are stored as catenae in the lexicon. In the actual syntax, however, some idioms can be broken up by various functional constructions.

The catena-based analysis of idioms provides a basis for an understanding of meaning compositionality. The Principle of Compositionality can in fact be maintained. Units of meaning are being assigned to catenae, whereby many of these catenae are not constituents.

See also[edit]

Multiword Expression[edit]

A multiword expression is "lexical units larger than a word that can bear both idiomatic and compositional meanings. (...) the term multi-word expression is used as a pre-theoretical label to include the range of phenomena that goes from collocations to fixed expressions." It is a problem in natural language processing when trying to translate lexical units such as idioms.[20][21][22]

References[edit]

- ^ The Oxford companion to the English language (1992:495f.)

- ^ Jackendoff (1997).

- ^ Martin, Gary. "'Spill the beans' - the meaning and origin of this phrase". Phrasefinder.

- ^ "etymology - Origin of "spill the beans" - English Language & Usage Stack Exchange". English.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ^ Gary Martin. "Break a leg". The Phrase Finder.

- ^ Radford (2004:187f.)

- ^ Portner (2005:33f).

- ^ Mel’čuk (1995:167–232).

- ^ For Saeed's definition, see Saeed (2003:60).

- ^ a b c Horn, George (2003). "Idioms, Metaphors, and Syntactic Mobility". Journal of Linguistics. 39: 245–273.

- ^ Keizer, Evelien (2016). "Idiomatic expressions in Functional Discourse Grammar". Linguistics. 54: 981–1016.

- ^ Mostafa, Massrura (2010). "Variation in V+the+N idioms". English Today. 26: 37–43.

- ^ O'Grady, William (1998). "The Syntax of Idioms". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 16: 279–312.

- ^ "Translation of the idiom kick the bucket in French". www.idiommaster.com. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ^ "Translation of the idiom kick the bucket in Italian". www.idiommaster.com. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ^ Gibbs, R. W. (1987)

- ^ "40 brilliant idioms that simply can't be translated literally". TED Blog. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ^ Culicver and Jackendoff (2005:32ff.)

- ^ Osborne and Groß (2012:173ff.)

- ^ Muller, Peter; Ohneiser, Ingeborg; Olsen, Susan; Rainer, Franz (Oct 2011). Word Formation, An International Handbook of the Languages of Europe (HSK Series) (PDF). Berlin: De Gruyter. p. Chapter 25: Multword Expressions. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Sag, Ivan A; Baldwin, Timothy; Bond, Francis; Copestake, Ann; Flickinger, Dan (2002). "Multiword Expressions: A Pain in the Neck for NLP". Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2276. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/3-540-45715-1_1. ISBN 978-3-540-43219-7. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Sailer M, Markantonatou S, eds. (2018). Multiword expressions: Insights from a multi-lingual perspective (pdf). Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1182583. ISBN 978-3-96110-063-7.

Bibliography[edit]

- Crystal, A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Gibbs, R. 1987. "Linguistic factors in children's understanding of idioms". Journal of Child Language, 14, 569–586.

- Jackendoff, R. 1997. The architecture of the language faculty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Jurafsky, D. and J. Martin. 2008. Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition. Dorling Kindersley (India): Pearson Education, Inc.

- Leaney, C. 2005. In the know: Understanding and using idioms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mel’čuk, I. 1995. "Phrasemes in language and phraseology in linguistics". In M. Everaert, E.-J. van der Linden, A. Schenk and R. Schreuder (eds.), Idioms: Structural and psychological perspectives, 167–232. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- O’Grady, W. 1998. "The syntax of idioms". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16, 79–312.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. "Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar". Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163–214.

- Portner, P. 2005. What is meaning?: Fundamentals of formal semantics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Radford, A. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Saeed, J. 2003. Semantics. 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

External links[edit]

| Look up idiom, Category:Idioms by language, or Category:English idioms in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Idioms – Online English idioms dictionary.

- babelite.org – Online cross-language idioms dictionary in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese.