Mathematical table

The lead section of this article may need to be rewritten. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Mathematical tables are lists of numbers showing the results of calculation with varying arguments. Before calculators were cheap and plentiful, people would use such tables to simplify and drastically speed up computation. Tables of logarithms and trigonometric functions were common in math and science textbooks. Specialized tables were published for applications such as astronomy, celestial navigation and statistics.

Contents

A simple example[edit]

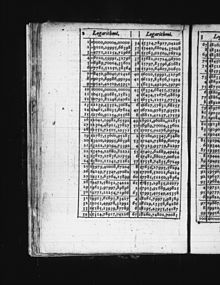

To compute the sine function of 75 degrees, 9 minutes, 50 seconds[1] using a table of trigonometric functions such as the Bernegger table from 1619 illustrated here, one might simply round up to 75 degrees, 10 minutes and then find the 10 minute entry on the 75 degree page, shown above-right, which is 0.9666746.

However, this answer is only accurate to four decimal places. If one wanted greater accuracy, one could interpolate linearly as follows:

From the Bernegger table:

- sin (75° 10′) = 0.9666746

- sin (75° 9′) = 0.9666001

The difference between these values is 0.0000745.

Since there are 60 seconds in a minute of arc, we multiply the difference by 50/60 to get a correction of (50/60)*0.0000745 ≈ 0.0000621; and then add that correction to sin (75° 9′) to get :

- sin (75° 9′ 50″) ≈ sin (75° 9′) + 0.0000621 = 0.9666001 + 0.0000621 = 0.9666622

A modern calculator gives sin (75° 9′ 50″) = 0.96666219991, so our interpolated answer is accurate to the 7-digit precision of the Bernegger table.

For tables with greater precision (more digits per value), higher order interpolation may be needed to get full accuracy.[2] In the era before electronic computers, interpolating table data in this manner was the only practical way to get high accuracy values of mathematical functions needed for applications such as navigation, astronomy and surveying.

To understand the importance of accuracy in applications like navigation note that at sea level one minute of arc along the Earth's equator or a meridian (indeed, any great circle) equals approximately one nautical mile (1.852 km or 1.151 mi).

History and use[edit]

The first tables of trigonometric functions known to be made were by Hipparchus (c.190 – c.120 BCE) and Menelaus (c.70–140 CE), but both have been lost. Along with the surviving table of Ptolemy (c. 90 – c.168 CE), they were all tables of chords and not of half-chords, i.e. the sine function.[3] The table produced by the Indian mathematician Āryabhaṭa is considered the first sine table ever constructed.[3] Āryabhaṭa's table remained the standard sine table of ancient India. There were continuous attempts to improve the accuracy of this table, culminating in the discovery of the power series expansions of the sine and cosine functions by Madhava of Sangamagrama (c.1350 – c.1425), and the tabulation of a sine table by Madhava with values accurate to seven or eight decimal places.

Tables of common logarithms were used until the invention of computers and electronic calculators to do rapid multiplications, divisions, and exponentiations, including the extraction of nth roots.

Mechanical special-purpose computers known as difference engines were proposed in the 19th century to tabulate polynomial approximations of logarithmic functions – i.e. to compute large logarithmic tables. This was motivated mainly by errors in logarithmic tables made by the human computers of the time. Early digital computers were developed during World War II in part to produce specialized mathematical tables for aiming artillery. From 1972 onwards, with the launch and growing use of scientific calculators, most mathematical tables went out of use.

One of the last major efforts to construct such tables was the Mathematical Tables Project that was started in 1938 as a project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), employing 450 out-of-work clerks to tabulate higher mathematical functions, and lasted through World War II.

Tables of special functions are still used; for example, the use of tables of values of the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution – so-called standard normal tables – remains commonplace today, especially in schools.

Creating tables stored in random-access memory is a common code optimization technique in computer programming, where the use of such tables speeds up calculations in those cases where a table lookup is faster than the corresponding calculations (particularly if the computer in question doesn't have a hardware implementation of the calculations). In essence, one trades computing speed for the computer memory space required to store the tables.

Tables of logarithms[edit]

Tables containing common logarithms (base-10) were extensively used in computations prior to the advent of computers and calculators because logarithms convert problems of multiplication and division into much easier addition and subtraction problems. Base-10 logarithms have an additional property that is unique and useful: The common logarithm of numbers greater than one that differ only by a factor of a power of ten all have the same fractional part, known as the mantissa. Tables of common logarithms typically included only the mantissas; the integer part of the logarithm, known as the characteristic, could easily be determined by counting digits in the original number.

The fractional part of the common logarithm of numbers greater than zero but less than one is just 1 minus the mantissa of the same number with the decimal point shifted to the right of the first non-zero digit. But same mantissa could be (and was) used for numbers less than one by offsetting the characteristic. Thus a single table of common logarithms can be used for the entire range of positive decimal numbers.[4] See common logarithm for details on the use of characteristics and mantissas.

History[edit]

Michael Stifel published Arithmetica integra in Nuremberg in 1544 which contains a table[5] of integers and powers of 2 that has been considered an early version of a logarithmic table.[6][7]

The method of logarithms was publicly propounded by John Napier in 1614, in a book entitled Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio (Description of the Wonderful Rule of Logarithms).[8] The book contained fifty-seven pages of explanatory matter and ninety pages of tables related to natural logarithms. The English mathematician Henry Briggs visited Napier in 1615, and proposed a re-scaling of Napier's logarithms to form what is now known as the common or base-10 logarithms. Napier delegated to Briggs the computation of a revised table, and they later published, in 1617, Logarithmorum Chilias Prima ("The First Thousand Logarithms"), which gave a brief account of logarithms and a table for the first 1000 integers calculated to the 14th decimal place.

The computational advance available via common logarithms, the converse of powered numbers or exponential notation, was such that it made calculations by hand much quicker.

See also[edit]

- Abramowitz and Stegun Handbook of Mathematical Functions

- Difference engine

- Ephemeris

- Group table

- History of logarithms

- Nautical almanac

- Matrix

- Multiplication table

- Random number table

- Table (information)

- Truth table

- Jurij Vega

References[edit]

- ^ The longitude of Philadelphia City Hall

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Introduction §4

- ^ a b J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (June 1996). "The trigonometric functions". Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ E. R. Hedrick, Logarithmic and Trigonometric Tables (Macmillan, New York, 1913).

- ^ Stifelio, Michaele (1544), Arithmetica Integra, London: Iohan Petreium

- ^ Bukhshtab, A.A.; Pechaev, V.I. (2001) [1994], "Arithmetic", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- ^ Vivian Shaw Groza and Susanne M. Shelley (1972), Precalculus mathematics, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 182, ISBN 978-0-03-077670-0

- ^ Ernest William Hobson (1914), John Napier and the invention of logarithms, 1614, Cambridge: The University Press

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003), The history of mathematical tables: from Sumer to spreadsheets, Oxford scholarship online, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850841-0

External links[edit]

- http://locomat.loria.fr : A census of mathematical and astronomical tables.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mathematical tables. |