Roman numerals

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

The numeric system represented by Roman numerals originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers in this system are represented by combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet. Roman numerals, as used today, employ seven symbols, each with a fixed integer value, as follows:[1]

The use of Roman numerals continued long after the decline of the Roman Empire. From the 14th century on, Roman numerals began to be replaced in most contexts by the more convenient Arabic numerals; however, this process was gradual, and the use of Roman numerals persists in some minor applications to this day.

Contents

Roman numeric system

Basic decimal pattern

The original pattern for Roman numerals used the symbols I, V, and X (1, 5, and 10) as simple tally marks. Each marker for 1 (I) added a unit value up to 5 (V), and was then added to (V) to make the numbers from 6 to 9:

- I, II, III, IIII, V, VI, VII, VIII, VIIII, X.

The numerals for 4 (IIII) and 9 (VIIII) proved problematic (among other things, they are easily confused with III and VIII, especially at a quick glance), and are generally replaced with IV (one less than 5) and IX (one less than 10). This feature of Roman numerals is called subtractive notation.

The numbers from 1 to 10 (including subtractive notation for 4 and 9) are expressed in Roman numerals as follows:

- I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X.[2]

The system being basically decimal, tens and hundreds follow the same underlying pattern. This is the key to understanding Roman numerals:

Thus 10 to 100 (counting in tens, with X taking the place of I, L taking the place of V and C taking the place of X):

- X, XX, XXX, XL, L, LX, LXX, LXXX, XC, C.

Note that 40 (XL) and 90 (XC) follow the same subtractive pattern as 4 and 9, avoiding the confusing XXXX.

Similarly, 100 to 1000 (counting in hundreds):

- C, CC, CCC, CD, D, DC, DCC, DCCC, CM, M.

Again - 400 (CD) and 900 (CM) follow the standard subtractive pattern, avoiding CCCC.

In the absence of standard symbols for 5,000 and 10,000 the pattern breaks down at this point - in modern usage M is repeated up to three times. The Romans had several ways to indicate larger numbers, but for practical purposes Roman Numerals for numbers larger than 3,999 are seldom if ever used nowadays, and this suffices.

- M, MM, MMM.

Many numbers include hundreds, units and tens. The Roman numeral system being basically decimal, each power of ten is added in descending sequence from left to right, as with Arabic numerals. For example:

- 39 = "Thirty nine" (XXX+IX) = XXXIX.

- 246 = "Two hundred and forty six" (CC+XL+VI) = CCXLVI.

- 421 = "Four hundred and twenty one" (CD+XX+I) = CDXXI.

As each power of ten (or "place") has its own notation there is no need for place keeping zeros, so "missing places" are ignored, as in Latin (and English) speech, thus:

- 160 = "One hundred and sixty" (C+LX) = CLX

- 207 = "Two hundred and seven" (CC+VII) = CCVII

- 1066 = "A thousand and sixty six" (M+LX+VI) = MLXVI.[3][4]

Roman numerals for large numbers are nowadays seen mainly in the form of year numbers (other uses are detailed later in this article), as in these examples:

- 1776 (M+DCC+LXX+VI) = MDCCLXXVI (the date written on the book held by the Statue of Liberty).[5]

- 1954 (M+CM+L+IV) = MCMLIV (as in the trailer for the movie The Last Time I Saw Paris)[6]

- 1990 (M+CM+XC) = MCMXC (used as the title of musical project Enigma's debut album MCMXC a.D., named after the year of its release).

- 2014 (MM+X+IV) = MMXIV (the year of the games of the XXII (22nd) Olympic Winter Games (in Sochi)

- The current year (2019) is MMXIX.

Alternative forms

The "standard" forms described above reflect typical modern usage rather than an unchanging and universally accepted convention. Usage in ancient Rome varied greatly and remained inconsistent in medieval times. There is still no official "binding" standard, which makes the elaborate "rules" used in some sources to distinguish between "correct" and "incorrect" forms highly problematic[7].

- "Classical" inscriptions (those dating from the Roman period) not infrequently use IIII for "4" instead of IV. Other "non-subtractive" forms, such as VIIII for IX, are also sometimes seen, although they are less common. On the numbered gates to the colosseum, for instance, IV is systematically avoided in favour of IIII, but other "subtractives" apply, so that gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.[8] Isaac Asimov speculates that the use of "IV", as the initial letters of "IVPITER" (the classical Latin spelling of the name of the Roman god Jupiter) may have been felt to have been impious in this context.[9]

- Clock faces that use Roman numerals normally show IIII for four o'clock but IX for nine o'clock, a practice that goes back to very early clocks such as the Wells Cathedral clock of the late 14th century.[10][11][12] However, this is far from universal: for example, the clock on the Palace of Westminster, Big Ben, uses a "normal" IV.[11]

- XIIX or IIXX are sometimes used for "18" instead of XVIII. The Latin word for "eighteen" is often rendered as the equivalent of "two less than twenty" (duodeviginti) which may be the source of this usage.

- The standard forms for 98 and 99 are XCVIII and XCIX, as described in the "decimal pattern" section above, but these numbers are occasionally rendered as IIC and IC[13], perhaps originally from the Latin duodecentum and undecentum (two/one less than a hundred).

- Sometimes V and L are not used, with instances such as IIIIII and XXXXXX rather than VI or LX.[14][15]

- Most non-standard numerals other than those described above - such as VXL for 45, instead of the standard XLV are modern and may be due to error rather than being genuine variant usage. In the early years of the 20th century, different representations of 900 (conventionally CM) appeared in several inscribed dates. For instance, 1910 is shown on Admiralty Arch, London, as MDCCCCX rather than MCMX, while on the north entrance to the Saint Louis Art Museum, 1903 is inscribed as MDCDIII rather than MCMIII.[16]

History

Pre-Roman times and ancient Rome

Although Roman numerals came to be written with letters of the Roman alphabet, they were originally independent symbols. The Etruscans, for example, used 𐌠, 𐌡, 𐌢, 𐌣, 𐌚, and ⊕ for I, V, X, L, C, and M, of which only I and X happened to be letters in their alphabet.

Hypotheses about the origin of Roman numerals

Tally marks

One hypothesis is that the Etrusco-Roman numerals actually derive from notches on tally sticks, which continued to be used by Italian and Dalmatian shepherds into the 19th century.[17]

Thus, ⟨I⟩ descends not from the letter ⟨I⟩ but from a notch scored across the stick. Every fifth notch was double cut i.e. ⋀, ⋁, ⋋, ⋌, etc.), and every tenth was cross cut (X), IIIIΛIIIIXIIIIΛIIIIXII..., much like European tally marks today. This produced a positional system: Eight on a counting stick was eight tallies, IIIIΛIII, or the eighth of a longer series of tallies; either way, it could be abbreviated ΛIII (or VIII), as the existence of a Λ implies four prior notches. By extension, eighteen was the eighth tally after the first ten, which could be abbreviated X, and so was XΛIII. Likewise, number four on the stick was the I-notch that could be felt just before the cut of the Λ (V), so it could be written as either IIII or IΛ (IV). Thus the system was neither additive nor subtractive in its conception, but ordinal. When the tallies were transferred to writing, the marks were easily identified with the existing Roman letters I, V and X. The tenth V or X along the stick received an extra stroke. Thus 50 was written variously as N, И, K, Ψ, ⋔, etc., but perhaps most often as a chicken-track shape like a superimposed V and I: ᗐ. This had flattened to ⊥ (an inverted T) by the time of Augustus, and soon thereafter became identified with the graphically similar letter L. Likewise, 100 was variously Ж, ⋉, ⋈, H, or as any of the symbols for 50 above plus an extra stroke. The form Ж (that is, a superimposed X and I) came to predominate. It was written variously as >I< or ƆIC, was then abbreviated to Ɔ or C, with C variant finally winning out because, as a letter, it stood for centum, Latin for "hundred".

The hundredth V or X was marked with a box or circle. Thus 500 was like a Ɔ superimposed on a ⋌ or ⊢ — that is, like a ⟨Þ⟩ with a cross bar,— becoming D or Ð by the time of Augustus, under the graphic influence of the letter ⟨D⟩. It was later identified as the letter D; an alternative symbol for "thousand" was a bracketed (I) (or CIƆ), and half of a thousand or "five hundred" is the right half of the symbol, I) (or IƆ), and this may have been converted into ⟨D⟩.[18] This at least was the etymology given to it later on.

Meanwhile, 1000 was a circled or boxed X: Ⓧ, ⊗, ⊕, and by Augustinian times was partially identified with the Greek letter Φ phi. Over time, the symbol changed to Ψ and ↀ. The latter symbol further evolved into ∞, then ⋈, and eventually changed to M under the influence of the Latin word mille "thousand".

Hand signals

Alfred Hooper has an alternative hypothesis for the origin of the Roman numeral system, for small numbers.[19] Hooper contends that the digits are related to hand gestures for counting. For example, the numbers I, II, III, IIII correspond to the number of fingers held up for another to see. V, then represents that hand upright with fingers together and thumb apart. Numbers 6–10, are represented with two hands as follows (left hand, right hand) 6=(V,I), 7=(V,II), 8=(V,III), 9=(V,IIII), 10=(V,V) and X results from either crossing of the thumbs, or holding both hands up in a cross.

Another possibility is that each I represents a finger and V represents the thumb of one hand. This way the numbers between 1–10 can be counted on one hand using the order: (P=pinky, R=ring, M=middle, I=index, T=thumb N=no fingers/other hand) I=P, II=PR, III=PRM, IV=IT, V=T, VI=TP, VII=TPR, VIII=TPRM, IX=IN, X=N. This pattern can also be continued using the other hand with the fingers representing X and the thumb L.

Intermediate symbols deriving from few original symbols

A third hypothesis about the origins states that the basic ciphers were I, X, C and Φ (or ⊕) and that the intermediary ones were derived from taking half of those (half an X is V, half a C is L and half a Φ/⊕ is D).[20] The Φ was later replaced with M, the initial of mille (the Latin word for "thousand").

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Lower case, minuscule, letters were developed in the Middle Ages, well after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, and since that time lower-case versions of Roman numbers have also been commonly used: i, ii, iii, iv, and so on.

Since the Middle Ages, a "j" has sometimes been substituted for the final "i" of a "lower-case" Roman numeral, such as "iij" for 3 or "vij" for 7. This "j" can be considered a swash variant of "i". The use of a final "j" is still used in medical prescriptions to prevent tampering with or misinterpretation of a number after it is written.[21][22]

Numerals in documents and inscriptions from the Middle Ages sometimes include additional symbols, which today are called "medieval Roman numerals". Some simply substitute another letter for the standard one (such as "A" for "V", or "Q" for "D"), while others serve as abbreviations for compound numerals ("O" for "XI", or "F" for "XL"). Although they are still listed today in some dictionaries, they are long out of use.[23]

| Number | Medieval abbreviation |

Notes and etymology |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | A | Resembles an upside-down V. Also said to equal 500. |

| 6 | Ϛ | Either from a ligature of VI, or from digamma (ϛ), the Greek numeral 6 (sometimes conflated with the stigma ligature).[24] |

| 7 | S, Z | Presumed abbreviation of septem, Latin for 7. |

| 9.5 | X ̷ | Scribal abbreviation, an x with a slash through it. Likewise, IX ̷ represented 8.5 |

| 11 | O | Presumed abbreviation of onze, French for 11. |

| 40 | F | Presumed abbreviation of English forty. |

| 70 | S | Also could stand for 7, with the same derivation. |

| 80 | R | |

| 90 | N | Presumed abbreviation of nonaginta, Latin for 90. (N.B. N is also used for "nothing" (nullus)). |

| 150 | Y | Possibly derived from the lowercase y's shape. |

| 151 | K | Unusual, origin unknown; also said to stand for 250.[25] |

| 160 | T | Possibly derived from Greek tetra, as 4 × 40 = 160. |

| 200 | H | Could also stand for 2 (see also 𐆙, the symbol for the dupondius). From a barring of two I's. |

| 250 | E | |

| 300 | B | |

| 400 | P, G | |

| 500 | Q | Redundant with D; abbreviates quingenti, Latin for 500. |

| 800 | Ω | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 2000 | Z |

Chronograms, messages with dates encoded into them, were popular during the Renaissance era. The chronogram would be a phrase containing the letters I, V, X, L, C, D, and M. By putting these letters together, the reader would obtain a number, usually indicating a particular year.

Modern use

By the 11th century, Arabic numerals had been introduced into Europe from al-Andalus, by way of Arab traders and arithmetic treatises. Roman numerals, however, proved very persistent, remaining in common use in the West well into the 14th and 15th centuries, even in accounting and other business records (where the actual calculations would have been made using an abacus). Replacement by their more convenient "Arabic" equivalents was quite gradual, and Roman numerals are still used today in certain contexts. A few examples of their current use are:

- Names of monarchs and popes, e.g. Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI. These are referred to as regnal numbers and are usually read as ordinals; e.g. II is pronounced "the second". This tradition began in Europe sporadically in the Middle Ages, gaining widespread use in England during the reign of Henry VIII. Previously, the monarch was not known by numeral but by an epithet such as Edward the Confessor. Some monarchs (e.g. Charles IV of Spain and Louis XIV of France) seem to have preferred the use of IIII instead of IV on their coinage (see illustration).

- Generational suffixes, particularly in the US, for people sharing the same name across generations, for example William Howard Taft IV.

- In the French Republican Calendar, initiated during the French Revolution, years were numbered by Roman numerals – from the year I (1792) when this calendar was introduced to the year XIV (1805) when it was abandoned.

- The year of production of films, television shows and other works of art within the work itself. It has been suggested – by BBC News, perhaps facetiously – that this was originally done "in an attempt to disguise the age of films or television programmes."[26] Outside reference to the work will use regular Arabic numerals.

- Hour marks on timepieces. In this context, 4 is often written IIII.

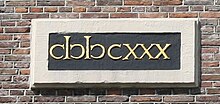

- The year of construction on building faces and cornerstones.

- Page numbering of prefaces and introductions of books, and sometimes of appendices and annexes, too.

- Book volume and chapter numbers, as well as the several acts within a play (e.g. Act iii, Scene 2).

- Sequels to some films, video games, and other works (as in Rocky II).

- Outlines that use numbers to show hierarchical relationships.

- Occurrences of a recurring grand event, for instance:

- The Summer and Winter Olympic Games (e.g. the XXI Olympic Winter Games; the Games of the XXX Olympiad)

- The Super Bowl, the annual championship game of the National Football League (e.g. Super Bowl XXXVII; Super Bowl 50 is a one-time exception[27])

- WrestleMania, the annual professional wrestling event for the WWE (e.g. WrestleMania XXX). This usage has also been inconsistent.

Specific disciplines

In astronomy, the natural satellites or "moons" of the planets are traditionally designated by capital Roman numerals appended to the planet's name. For example, Titan's designation is Saturn VI.

In chemistry, Roman numerals are often used to denote the groups of the periodic table. They are also used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, for the oxidation number of cations which can take on several different positive charges. They are also used for naming phases of polymorphic crystals, such as ice.

In education, school grades (in the sense of year-groups rather than test scores) are sometimes referred to by a Roman numeral; for example, "grade IX" is sometimes seen for "grade 9".

In entomology, the broods of the thirteen and seventeen year periodical cicadas are identified by Roman numerals.

In advanced mathematics (including trigonometry, statistics, and calculus), when a graph includes negative numbers, its quadrants are named using I, II, III, and IV. These quadrant names signify positive numbers on both axes, negative numbers on the X axis, negative numbers on both axes, and negative numbers on the Y axis, respectively. The use of Roman numerals to designate quadrants avoids confusion, since Arabic numerals are used for the actual data represented in the graph.

In military unit designation, Roman numerals are often used to distinguish between units at different levels. This reduces possible confusion, especially when viewing operational or strategic level maps. In particular, army corps are often numbered using Roman numerals (for example the American XVIII Airborne Corps or the WW2-era German III Panzerkorps) with Arabic numerals being used for divisions and armies.

In music, Roman numerals are used in several contexts:

- Movements are often numbered using Roman numerals.

- In music theory, the diatonic functions are identified using Roman numerals. (See: Roman numeral analysis)

- Individual strings of stringed instruments, such as the violin, are often denoted by Roman numerals, with higher numbers denoting lower strings.

In pharmacy, Roman numerals are used in some contexts, including S to denote "one half" and N to mean "nothing".[28] (See the sections below on "zero" and "fractions".)

In photography, Roman numerals (with zero) are used to denote varying levels of brightness when using the Zone System.

In seismology, Roman numerals are used to designate degrees of the Mercalli intensity scale of earthquakes.

In sport the team containing the "top" players and representing a nation or province, a club or a school at the highest level in (say) rugby union is often called the "1st XV", while a cricket or American football team for younger or less experienced players might be the "3rd XI".

In tarot, Roman numerals (with zero) are used to denote the cards of the Major Arcana.

In theology and biblical scholarship, the Septuagint is often referred to as LXX, as this translation of the Old Testament into Greek is named for the legendary number of its translators (septuaginta being Latin for "seventy").

Modern use in continental Europe

Some uses that are rare or never seen in English speaking countries may be relatively common in parts of continental Europe. For instance:

Capital or small capital Roman numerals are widely used in Romance languages to denote centuries, e.g. the French xviiie siècle[29] and the Spanish siglo XVIII mean "18th century". Slavic languages in and adjacent to Russia similarly favour Roman numerals (XVIII век). On the other hand, in Slavic languages in Central Europe, like most Germanic languages, one writes "18." (with a period) before the local word for "century".

Mixed Roman and Arabic numerals are sometimes used in numeric representations of dates (especially in formal letters and official documents, but also on tombstones). The month is written in Roman numerals, while the day is in Arabic numerals: "14.VI.1789" and "VI.14.1789" both refer unambiguously to 14 June 1789.

Roman numerals are sometimes used to represent the days of the week in hours-of-operation signs displayed in windows or on doors of businesses,[30] and also sometimes in railway and bus timetables. Monday, taken as the first day of the week, is represented by I. Sunday is represented by VII. The hours of operation signs are tables composed of two columns where the left column is the day of the week in Roman numerals and the right column is a range of hours of operation from starting time to closing time. In the example case (left), the business opens from 10 am to 7 pm on weekdays, 10 AM to 5 pm on Saturdays and is closed on Sundays. Note that the listing uses 24-hour time.

Roman numerals may also be used for floor numbering.[31][32] For instance, apartments in central Amsterdam are indicated as 138-III, with both an Arabic numeral (number of the block or house) and a Roman numeral (floor number). The apartment on the ground floor is indicated as 138-huis.

In Italy, where roads outside built-up areas have kilometre signs, major roads and motorways also mark 100-metre subdivisionals, using Roman numerals from I to IX for the smaller intervals. The sign "IX | 17" thus marks kilometre 17.9.

A notable exception to the use of Roman numerals in Europe is in Greece, where Greek numerals (based on the Greek alphabet) are generally used in contexts where Roman numerals would be used elsewhere.

Special values

Zero

The number zero does not have its own Roman numeral, but the word nulla (the Latin word meaning "none") was used by medieval scholars in lieu of 0. Dionysius Exiguus was known to use nulla alongside Roman numerals in 525.[33][34] About 725, Bede or one of his colleagues used the letter N, the initial of nulla or of nihil (the Latin word for "nothing"), in a table of epacts, all written in Roman numerals.[35]

Fractions

Though the Romans used a decimal system for whole numbers, reflecting how they counted in Latin, they used a duodecimal system for fractions, because the divisibility of twelve (12 = 22 × 3) makes it easier to handle the common fractions of 1/3 and 1/4 than does a system based on ten (10 = 2 × 5). On coins, many of which had values that were duodecimal fractions of the unit as, they used a tally-like notational system based on twelfths and halves. A dot (•) indicated an uncia "twelfth", the source of the English words inch and ounce; dots were repeated for fractions up to five twelfths. Six twelfths (one half) was abbreviated as the letter S for semis "half". Uncia dots were added to S for fractions from seven to eleven twelfths, just as tallies were added to V for whole numbers from six to nine.[36]

Each fraction from 1/12 to 12/12 had a name in Roman times; these corresponded to the names of the related coins:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/12 | · | Uncia, unciae | "Ounce" |

| 2/12 = 1/6 | ·· or : | Sextans, sextantis | "Sixth" |

| 3/12 = 1/4 | ··· or ∴ | Quadrans, quadrantis | "Quarter" |

| 4/12 = 1/3 | ···· or ∷ | Triens, trientis | "Third" |

| 5/12 | ····· or ⁙ | Quincunx, quincuncis | "Five-ounce" (quinque unciae → quincunx) |

| 6/12 = 1/2 | S | Semis, semissis | "Half" |

| 7/12 | S· | Septunx, septuncis | "Seven-ounce" (septem unciae → septunx) |

| 8/12 = 2/3 | S·· or S: | Bes, bessis | "Twice" (as in "twice a third") |

| 9/12 = 3/4 | S··· or S∴ | Dodrans, dodrantis or nonuncium, nonuncii |

"Less a quarter" (de-quadrans → dodrans) or "ninth ounce" (nona uncia → nonuncium) |

| 10/12 = 5/6 | S···· or S∷ | Dextans, dextantis or decunx, decuncis |

"Less a sixth" (de-sextans → dextans) or "ten ounces" (decem unciae → decunx) |

| 11/12 | S····· or S⁙ | Deunx, deuncis | "Less an ounce" (de-uncia → deunx) |

| 12/12 = 1 | I | As, assis | "Unit" |

The arrangement of the dots was variable and not necessarily linear. Five dots arranged like (⁙) (as on the face of a die) are known as a quincunx, from the name of the Roman fraction/coin. The Latin words sextans and quadrans are the source of the English words sextant and quadrant.

Other Roman fractional notations included the following:

- 1/8 sescuncia, sescunciae (from sesqui- + uncia, i.e. 1½ uncias), represented by a sequence of the symbols for the semuncia and the uncia.

- 1/24 semuncia, semunciae (from semi- + uncia, i.e. ½ uncia), represented by several variant glyphs deriving from the shape of the Greek letter sigma (Σ), one variant resembling the pound sign without the horizontal line (𐆒) and another resembling the Cyrillic letter Є.

- 1/36 binae sextulae, binarum sextularum ("two sextulas") or duella, duellae, represented by a sequence of two reversed Ss (𐆓𐆓).

- 1/48 sicilicus, sicilici, represented by a reversed C (Ɔ).

- 1/72 sextula, sextulae (1/6 of an uncia), represented by a reversed S (𐆓).

- 1/144 = 12−2 dimidia sextula, dimidiae sextulae ("half a sextula"), represented by a reversed S crossed by a horizontal line (𐆔).

- 1/288 scripulum, scripuli (a scruple), represented by the symbol ℈.

- 1/1728 = 12−3 siliqua, siliquae, represented by a symbol resembling closing guillemets (𐆕).

Large numbers

A number of systems were developed for the expression of larger numbers that cannot be conveniently expressed using the normal seven letter symbols of conventional Roman numerals.

Apostrophus

One of these was the apostrophus,[37] in which 500 (usually written as "D") was written as |Ɔ, while 1,000, was written as C|Ɔ instead of "M".[18] This is a system of encasing numbers to denote thousands (imagine the Cs and Ɔs as parentheses), which has its origins in Etruscan numeral usage. The |Ɔ and C|Ɔ used to represent 500 and 1,000 most likely preceded, and subsequently influenced, the adoption of "D" and "M" in conventional Roman numerals.

In this system, an extra Ɔ denoted 500, and multiple extra Ɔs are used to denote 5,000, 50,000, etc. For example:

| Base number | C|Ɔ = 1,000 | CC|ƆƆ = 10,000 | CCC|ƆƆƆ = 100,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 extra Ɔ | |Ɔ = 500 | C|ƆƆ = 1,500 | CC|ƆƆƆ = 10,500 | CCC|ƆƆƆƆ = 100,500 |

| 2 extra Ɔs | |ƆƆ = 5,000 | CC|ƆƆƆƆ = 15,000 | CCC|ƆƆƆƆƆ = 105,000 | |

| 3 extra Ɔs | |ƆƆƆ = 50,000 | CCC|ƆƆƆƆƆƆ = 150,000 |

Sometimes C|Ɔ was reduced to ↀ for 1,000. John Wallis is often credited for introducing the symbol for infinity (modern ∞), and one conjecture is that he based it on this usage, since 1,000 was hyperbolically used to represent very large numbers. Similarly, |ƆƆ for 5,000 was reduced to ↁ; CC|ƆƆ for 10,000 to ↂ; |ƆƆƆ for 50,000 to ↇ; and CCC|ƆƆƆ for 100,000 to ↈ.[17]

Vinculum

Another system is the vinculum, in which conventional Roman numerals are multiplied by 1,000 by adding an "bar" or "overline".[17] Although mathematical historian David Eugene Smith disputes that this was part of ancient Roman usage,[38] the notation was certainly in use in the Middle Ages, and is sometimes suggested as a workable method for modern use, although it is not standardised as such.

Any hundreds, tens or units in the number are written in ordinary Roman numerals - but instead of M, MM or MMM, "barred" notation is used to express the thousands - which greatly expands the range of numbers expressible.

For instance:

- IV = 4,000

- IVDCXXVII = 4,627

- XXV = 25,000

- XXVCDLIX = 25,459

If this were ever to be applied consistently in our own times - then the main difficulty would be what to do with "M" - one way would be to do away with "M" altogether, except perhaps for CM (=900) - thus rendering MMXVIII as IIXVIII - or alternatively to retain "M" in its current usage, with the barred numerals starting at IV (=4,000). Retaining "M" would permit our numerals to run up to MMMCMXCIXCMXCIX (= 3,999,999).

Another inconsistent medieval usage was the addition of vertical lines (or brackets) before and after the numeral to multiply it by 10 (or 100): thus M for 10,000 as an alternative form for X. In combination with the overline the bracketed forms might be used to raise the multiplier to (say) ten (or one hundred) thousand, thus:

- VIII for 80,000 (or 800,000)

- XX for 200,000 (or 2,000,000)

Through all this, and whether any kind of vinculum notation or "barring" needs to be revived or not, this needs to be distinguished from the custom, once very common, of adding both underline and overline to a Roman numeral, simply to make it clear that it is a number, e.g. MCMLXVII.

See also

- Egyptian numerals

- Etruscan numerals

- Greek numerals

- Kharosthi numerals

- Roman abacus

- Proto-writing

- Roman numerals in Unicode

- Pentimal system

References

- ^ Gordon, Arthur E. (1982). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05079-7.

Alphabetic symbols for larger numbers, such as Q for 500,000, have also been used to various degrees of standardization.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-49534-6.

- ^ Dela Cruz, M. L. P.; Torres, H. D. (2009). Number Smart Quest for Mastery: Teacher's Edition. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 9789712352164.

- ^ Martelli, Alex; Ascher, David (2002). Python Cookbook. O'Reilly Media Inc. ISBN 978-0-596-00167-4.

- ^ "What book is the Statue of Liberty holding? What is its significance?". Quora.

- ^ Hayes, David P. "Guide to Roman Numerals". Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (23 February 1990). "What is the proper way to style Roman numerals for the 1990s?". The Straight Dope.

- ^ "360:12 tables, 24 chairs, and plenty of chalk". Roman Numerals…not quite so simple.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1966). Asimov On Numbers (PDF). Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 12.

- ^ Milham, W.I. (1947). Time & Timekeepers. New York: Macmillan. p. 196.

- ^ a b Pickover, Clifford A. (2003), Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning, Oxford University Press, p. 282, ISBN 978-0-19-534800-2.

- ^ Adams, Cecil; Zotti, Ed (1988). More of the straight dope. Ballantine Books. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-345-35145-6..

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin H. (1879). Latin grammar. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 150.

- ^ Reynolds, Joyce Maire; Spawforth, Anthony J. S. (1996). "numbers, Roman". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Anthony. Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin Hall (1923). The Revised Latin Primer. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- ^ "Gallery: Museum's North Entrance (1910)". Saint Louis Art Museum. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

The inscription over the North Entrance to the Museum reads: "Dedicated to Art and Free to All MDCDIII." These roman numerals translate to 1903, indicating that the engraving was part of the original building designed for the 1904 World's Fair.

- ^ a b c Ifrah, Georges (2000). The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. Translated by David Bellos, E. F. Harding, Sophie Wood, Ian Monk. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ a b Asimov, Isaac (1966). Asimov On Numbers. Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 9.

- ^ Alfred Hooper. The River Mathematics (New York, H. Holt, 1945).

- ^ Keyser, Paul (1988). "The Origin of the Latin Numerals 1 to 1000". American Journal of Archaeology. 92: 529–546. JSTOR 505248.

- ^ Sturmer, Julius W. Course in Pharmaceutical and Chemical Arithmetic, 3rd ed. (LaFayette, IN: Burt-Terry-Wilson, 1906). p25. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Bastedo, Walter A. Materia Medica: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Prescription Writing for Students and Practitioners, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1919) p582. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Capelli, A. Dictionary of Latin Abbreviations. 1912.

- ^ Perry, David J. Proposal to Add Additional Ancient Roman Characters to UCS Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Bang, Jørgen. Fremmedordbog, Berlingske Ordbøger, 1962 (Danish)

- ^ Owen, Rob (13 January 2012). "TV Q&A: ABC News, 'Storage Wars' and 'The Big Bang Theory'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ NFL won't use Roman numerals for Super Bowl 50 Archived 1 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Football League. Retrieved 5 November 2014

- ^ Bachenheimer, Bonnie S. (2010). Manual for Pharmacy Technicians. ISBN 1-58528-307-X.

- ^ Lexique des règles typographiques en usage à l'imprimerie nationale (in French) (6th ed.). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. March 2011. p. 126. ISBN 978-2-7433-0482-9. On composera en chiffres romains petites capitales les nombres concernant : ↲ 1. Les siècles.

- ^ Beginners latin Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 1 December 2013

- ^ Roman Arithmetic Archived 22 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Southwestern Adventist University. Retrieved 1 December 2013

- ^ Roman Numerals History Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2013

- ^ Faith Wallis, trans. Bede: The Reckoning of Time (725), Liverpool, Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004. ISBN 0-85323-693-3.

- ^ Byrhtferth's Enchiridion (1016). Edited by Peter S. Baker and Michael Lapidge. Early English Text Society 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-722416-8.

- ^ C. W. Jones, ed., Opera Didascalica, vol. 123C in Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina.

- ^ Maher, David W.; Makowski, John F., "Literary Evidence for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions Archived August 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine", Classical Philology 96 (2011): 376–399.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary".

- ^ Smith, David Eugene (1958) [1925], History of Mathematics, II, p. 60, ISBN 0-486-20430-8

Sources

- Menninger, Karl (1992). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-27096-8.

Further reading

- Aczel, Amir D. 2015. Finding Zero: A Mathematician's Odyssey to Uncover the Origins of Numbers. 1st edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goines, David Lance. A Constructed Roman Alphabet: A Geometric Analysis of the Greek and Roman Capitals and of the Arabic Numerals. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1982.

- Houston, Stephen D. 2012. The Shape of Script: How and Why Writing Systems Change. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Taisbak, Christian M. 1965. "Roman numerals and the abacus." Classica et medievalia 26: 147–60.

| Look up Appendix:Roman numerals or roman numeral in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman numerals. |

| Library resources about Roman numerals |