Mixed reality

Mixed reality (MR), sometimes referred to as hybrid reality,[1] is the merging of real and virtual worlds to produce new environments and visualizations where physical and digital objects co-exist and interact in real time. Mixed reality takes place not only in the physical world or the virtual world,[1] but is a mix of reality and virtual reality, encompassing both augmented reality and augmented virtuality[2] via immersive technology. The first immersive mixed reality system, providing enveloping sight, sound, and touch was the Virtual Fixtures platform developed at the U.S. Air Force's Armstrong Laboratories in the early 1990s. In a study published in 1992, the Virtual Fixtures project at the U.S. Air Force demonstrated for the first time that human performance could be significantly amplified by the introduction of spatially registered virtual objects overlaid on top of a person's direct view of a real physical environment.[3]

Contents

Virtual reality (VR) versus augmented reality (AR) versus mixed reality (MR)[edit]

The definitions in the modern contemporary economy makes the distinction between VR, AR and MR very clear:[4]

- Virtual reality (VR) immerses users in a fully artificial digital environment.

- Augmented reality (AR) overlays virtual objects on the real-world environment.

- Mixed reality (MR) not just overlays but anchors virtual objects to the real world and allows the user to interact with the virtual objects.

Definition[edit]

Virtuality continuum and mediality continuum[edit]

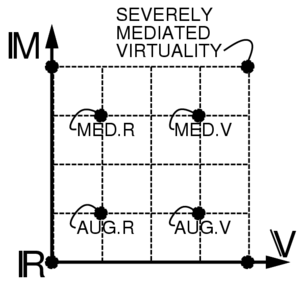

In 1994 Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino defined a mixed reality as "...anywhere between the extrema of the virtuality continuum" (VC),[2] where the virtuality continuum extends from the completely real through to the completely virtual environment with augmented reality and augmented virtuality ranging between. The first fully immersive mixed reality system was the Virtual Fixtures platform developed at US Air Force, Armstrong Labs in 1992 by Louis Rosenberg to enable human users to control robots in real-world environments that included real physical objects and 3D virtual overlays called "fixtures" that were added enhance human performance of manipulation tasks. Published studies showed that by introducing virtual objects into the real world, significant performance increases could be achieved by human operators.[6][7]

The continuum of mixed reality is one of the two axes in Steve Mann's concept of mediated reality as implemented by various welding helmets and wearable computers and wearable photographic systems he created in the 1970s and early 1980s,[8][9][10][11][12] the second axis being the mediality continuum, which includes, for example, Diminished Reality (as implemented in a welding helmet or eyeglasses that can block out advertising or replace real-world ads with useful information)[13][14]

"The conventionally held view of a Virtual Reality (VR) environment is one in which the participant-observer is totally immersed in, and able to interact with, a completely synthetic world. Such a world may mimic the properties of some real-world environments, either existing or fictional; however, it can also exceed the bounds of physical reality by creating a world in which the physical laws ordinarily governing space, time, mechanics, material properties, etc. no longer hold. What may be overlooked in this view, however, is that the VR label is also frequently used in association with a variety of other environments, to which total immersion and complete synthesis do not necessarily pertain, but which fall somewhere along a virtuality continuum. In this paper we focus on a particular subclass of VR related technologies that involve the merging of real and virtual worlds, which we refer to generically as Mixed Reality (MR)."

Interreality physics[edit]

In a physics context, the term "interreality system"[15] refers to a virtual reality system coupled to its real-world counterpart. A paper in the May 2007 issue of Physical Review E[16] describes an interreality system comprising a real physical pendulum coupled to a pendulum that only exists in virtual reality. This system apparently has two stable states of motion: a "Dual Reality" state in which the motion of the two pendula are uncorrelated and a "Mixed Reality" state in which the pendula exhibit stable phase-locked motion which is highly correlated. The use of the terms "mixed reality" and "interreality" in the context of physics is clearly defined but may be slightly different in other fields.

Augmented virtuality[edit]

Augmented virtuality (AV), is a subcategory of mixed reality which refers to the merging of real world objects into virtual worlds.[18]

As an intermediate case in the virtuality continuum, it refers to predominantly virtual spaces, where physical elements, e.g. physical objects or people, are dynamically integrated into, and can interact with, the virtual world in real time. This integration is achieved with the use of various techniques. Often streaming video from physical spaces (e.g., via webcam)[19] or using 3-dimensional digitalisation of physical objects.[20]

The use of real-world sensor information (e.g., gyroscopes) to control a virtual environment is an additional form of augmented virtuality, in which external inputs provide context for the virtual view.

Applications[edit]

A topic of much research, MR has found its way into a number of applications, evident in the arts and entertainment industries. However, MR is also branching out into the business, manufacturing and education worlds with systems such as these:

- IPCM – Interactive product content management

Moving from static product catalogs to interactive 3D smart digital replicas. Solution consists of application software products with scalable license model.

- SBL – Simulation based learning

Moving from e-learning to s-learning—state of the art in knowledge transfer for education. Simulation/VR based training, interactive experiential learning. Software and display solutions with scalable licensed curriculum development model.

- Military training

Combat reality is simulated and represented in complex layered data through HMD.

One of the possible applications mixed realities is for training military soldiers. Training solutions are often built on Commercial Off the Shelf (COTS) technologies. Examples of technologies used by the Army are Virtual Battlespace 3 and VirTra. As of 2018, the VirTra technology is being purchased by both the civilian and military law enforcement to train personnel in a variety of scenarios. These scenarios include active shooter; domestic violence; military traffic stops, etc.[21][22] Mixed reality technologies have been used by U.S. Army Research Laboratory scientists to study how this stress affects decision making. With mixed reality, researchers may safely study military service men and women in scenarios where soldiers would not likely survive.[23]

As of 2017, the U.S. Army was developing the Synthetic Training Environment (STE). STE is a collection of technologies for training purposes that has been estimated to include mixed reality. As of 2018, STE was still in development without a projected completion date. Some recorded goals of the simulation were to increase simulation training capabilities, and the availability of the environment to other systems, and to enhance realism.[24] It was claimed that training costs to be reduced with mixed reality environments like STE.[25][26] For example, using mixed environments could reduce the amount of munition expended during training.[27] It was reported in 2018 that STE would include representation of any part of the world's terrain for training purposes.[28] STE would offer a variety of training opportunities for squad brigade and combat teams, including, but not limited to Stryker, armory, and infantry.[29] It is estimated that STE will eventually replace the Army's Live, Virtual, Constructive – Integrated Architecture (LVC-IA).[30]

- Real Asset Virtualization Environment (RAVE)

3D Models of Manufacturing Assets (for example process manufacturing machinery) are incorporated into a virtual environment and then linked to real-time data associated with that asset. Avatars allow for multidisciplinary collaboration and decision making based on the data presented in the virtual environment. This example of Mixed Reality was pioneered and demonstrated by Kevyn Renner of Chevron Corporation for which a United States Patent 8,589,809, B2 "Methods and Systems for Conducting a Meeting in a Virtual Environment" was granted November 19, 2013.[31] One of the earliest patents describing mixed reality is shown by Michael DeLuca in United States Patent 6,064,354 "Stereoscopic user interface method and apparatus" granted May 16, 2000.[32]

- Remote working

Mixed reality allows a global workforce of remote teams to work together and tackle an organization's business challenges. No matter where they are physically located, an employee can strap on their headset and noise-canceling headphones and enter a collaborative, immersive virtual environment. Language barriers will become irrelevant as AR applications are able to accurately translate in real time. It also means a more flexible workforce. While many employers still use inflexible models of fixed working time and location, there is evidence that employees are more productive if they have greater autonomy over where, when and how they work. Some employees prefer loud work spaces, others need silence. Some work best in the morning, others at night. Employees also benefit from autonomy in how they work because everyone processes information differently. The classic VAK model for learning styles differentiates Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic learners.[33]

Machine maintenance is also a subject that can be executed with the help of mixed reality. Larger companies that have multiple manufacturing locations with a lot of machinery can use mixed reality to educate and instruct their employee. The machines need regular checkups and have to be adjusted every now and then. These adjustments are mostly done by humans, so these employees need to be informed about every small adjustment that needs to be done. By using mixed reality, employees from multiple locations can put on a headset, and get live instructions about the changes. Instructors can operate the representation that every employee sees and can glide through the production area, zooming in to technical details and explain every change of a machine. It has shown that a five-minute training session with such a mixed reality program has the same results as the employees reading a 50-page training manual.[34]

- Functional mockup

Mixed reality is applied in the industrial field in order to build mockups that combine physical and digital elements.[35]

- Consciousness

It has been hypothesised that a hybrid of mixed and virtual reality could pave the way for human consciousness to be transferred into digital form entirely - a concept known as Virternity, which would leverage blockchain to create its main platform.[36][37]

Display technologies[edit]

Here are some more commonly used MR display technologies:

Notable examples[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b de Souza e Silva, Adriana; Sutko, Daniel M. (2009). Digital Cityscapes: merging digital and urban playspaces. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- ^ a b P. Milgram and A. F. Kishino (1994). "Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays". IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems. pp. 1321–1329. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ Rosenberg, Louis B. (1992). "The Use of Virtual Fixtures As Perceptual Overlays to Enhance Operator Performance in Remote Environments". Technical Report AL-TR-0089, USAF Armstrong Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB OH, 1992.

- ^ Quora. "The Difference Between Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality And Mixed Reality". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ^ R. Freeman, A. Steed and B. Zhou, Rapid Scene Modelling, Registration and Specification for Mixed Reality Systems Archived 2007-02-06 at the Wayback Machine Proceedings of ACM Virtual Reality Software and Technology, pp. 147-150, Monterey, California, November 2005.

- ^ L. B. Rosenberg. The Use of Virtual Fixtures As Perceptual Overlays to Enhance Operator Performance in Remote Environments. Technical Report AL-TR-0089, USAF Armstrong Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB OH, 1992.

- ^ Rosenberg, Louis B. (1993). "Virtual fixtures as tools to enhance operator performance in telepresence environments". Telemanipulator Technology and Space Telerobotics. 2057: 10–21. doi:10.1117/12.164901.

- ^ Steve Mann, "Campus Canada", ISSN 0823-4531, p55 Feb-Mar 1985, pp58-59 Apr-May 1986, p72 Sep-Oct 1986

- ^ Impulse, Volume 12, Number 2, 1985

- ^ Quantigraphic camera promises HDR eyesight from Father of AR, by Chris Davies, SlashGear, Sep 12th 2012

- ^ IEEE Technology & Society 31(3)

- ^ Through the Glass, Lightly, IEEE Technology & Society, Volume 31, Number 3, Fall 2012, pages 10-14

- ^ Mann, S., & Fung, J. (2001). Videoorbits on EyeTap devices for deliberately diminished reality or altering the visual perception of rigid planar patches of a real world scene. Proceedings of the Second IEEE International Symposium on Mixed Reality, pp 48-55, March 14–15, 2001.

- ^ 关于智能眼镜 (About Smart Glasses), 36KR, 2016-01-09

- ^ J. van Kokswijk, Hum@n, Telecoms & Internet as Interface to Interreality Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine (Bergboek, The Netherlands, 2003).

- ^ V. Gintautas and A. W. Hubler, Experimental evidence for mixed reality states in an interreality system Phys. Rev. E 75, 057201 (2007).

- ^ LIV. "Mixed Reality Studio - The LIV Cube". LIV. Retrieved 2017-04-08.

- ^ P. Milgram and A. F. Kishino, Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, E77-D(12), pp. 1321–1329, 1994.

- ^ The Distributed Interactive Virtual Environment (DIVE)

- ^ "Introduction - Teleimmersion Lab". UC Berkeley.

- ^ Inc., VirTra,. "VirTra's Police Training Simulators Chosen by Three of the Largest U.S. Law Enforcement Departments". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ "How do police use VR? Very well | Police Foundation". www.policefoundation.org. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Patton, Debbie; Marusich, Laura (2015-03-09). 2015 IEEE International Multi-Disciplinary Conference on Cognitive Methods in Situation Awareness and Decision. pp. 145–150. doi:10.1109/COGSIMA.2015.7108190. ISBN 978-1-4799-8015-4.

- ^ Eagen, Andrew (June 2017). "Expanding Simulations as a Means of Tactical Training with Multinational Partners" (PDF). A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.[dead link]

- ^ Bukhari, Hatim; Andreatta, Pamela; Goldiez, Brian; Rabelo, Luis (2017-01-01). "A Framework for Determining the Return on Investment of Simulation-Based Training in Health Care". INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 54: 0046958016687176. doi:10.1177/0046958016687176. ISSN 0046-9580. PMC 5798742. PMID 28133988.

- ^ Smith, Roger (2010-02-01). "The Long History of Gaming in Military Training". Simulation & Gaming. 41 (1): 6–19. doi:10.1177/1046878109334330. ISSN 1046-8781.

- ^ Shufelt, Jr., J.W. (2006) A Vision for Future Virtual Training. In Virtual Media for Military Applications (pp. KN2-1 – KN2-12). Meeting Proceedings RTO-MP-HFM-136, Keynote 2. Neuilly-sur-Seine, France: RTO. Available from: http://www.rto.nato.int/abstracts.asp {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070613170605/http://www.rto.nato.int/Abstracts.asp |date=2007-06-13 }}

- ^ "STAND-TO!". www.army.mil. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ "Augmented reality may revolutionize Army training | U.S. Army Research Laboratory". www.arl.army.mil. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ "Army Shoots for Single Synthetic Training Environment". GovTechWorks. 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/patog/week47/OG/html/1396-3/US08589809-20131119.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ "United States Patent: 6064354 - Stereoscopic user interface method and apparatus".

- ^ Sena, Pete. "How The Growth Of Mixed Reality Will Change Communication, Collaboration And The Future Of The Workplace". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ The Manufacturer. "Manufacturers are successfully using mixed reality today". www.themanufacturer.com.

- ^ Barbieri, L.; et al. (2013). Mixed prototyping with configurable physical archetype for usability evaluation of product interfaces. Computers in Industry. 64 (3). pp. 310–323.

- ^ "Potential of Blockchain Technology as Protocol of Universal Virtual Reality". TurboFuture. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ^ Shirazi, Sina. "Pairing Augmented Reality with Virtual Reality".

Further reading[edit]

- Signer, Beat & Curtin, Timothy J. (2017). Tangible Holograms: Towards Mobile Physical Augmentation of Virtual Objects, Technical Report WISE Lab, WISE-2017-01, March 2017.

- Fleischmann, Monika; Strauss, Wolfgang (eds.) (2001). Proceedings of »CAST01//Living in Mixed Realities« Intl. Conf. On Communication of Art, Science and Technology, Fraunhofer IMK 2001, 401. ISSN 1618-1379 (Print), ISSN 1618-1387 (Internet).

- Interactive Multimedia Lab A research lab at the National University of Singapore focuses on Multi-modal Mixed Reality interfaces.

- Mixed Reality Geographical Information System (MRGIS)

- Costanza, E., Kunz, A., and Fjeld, M. 2009. Mixed Reality: A Survey Costanza, E., Kunz, A., and Fjeld, M. 2009. Mixed Reality: A Survey. In Human Machine interaction: Research Results of the MMI Program, D. Lalanne and J. Kohlas (Eds.) LNCS 5440, pp. 47–68.

- H. Regenbrecht and C. Ott and M. Wagner and T. Lum and P. Kohler and W. Wilke and E. Mueller, An Augmented Virtuality Approach to 3D Videoconferencing, Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE and ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, pp 290-291, 2003

- Kristian Simsarian and Karl-Petter Akesson, Windows on the World: An example of Augmented Virtuality, Interface Sixth International Conference Montpellier, Man-machine interaction, pp 68-71, 1997

- [permanent dead link] Mixed Reality Project: experimental applications on Mixed Reality (Augmented Reality, Augmented Virtuality) and Virtual Reality.

- Mixed Reality Scale – Milgram and Kishino's (1994) Virtuality Continuum paraphrase with examples.

- IEICE Transactions on Information Systems, Vol E77-D, No.12 December 1994 - A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays - Paul Milgram, Fumio Kishino

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Mixed reality at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mixed reality at Wikimedia Commons

_(2006).jpg/115px-HP_Tablet_PC_running_Windows_XP_(Tablet_PC_edition)_(2006).jpg)