Complex adaptive system

A complex adaptive system is a system in which a perfect understanding of the individual parts does not automatically convey a perfect understanding of the whole system's behavior.[1] The study of complex adaptive systems, a subset of nonlinear dynamical systems,[2] is highly interdisciplinary and blends insights from the natural and social sciences to develop system-level models and insights that allow for heterogeneous agents, phase transition, and emergent behavior.[3]

They are complex in that they are dynamic networks of interactions, and their relationships are not aggregations of the individual static entities, i.e., the behavior of the ensemble is not predicted by the behavior of the components. They are adaptive in that the individual and collective behavior mutate and self-organize corresponding to the change-initiating micro-event or collection of events.[4][5][1] They are a "complex macroscopic collection" of relatively "similar and partially connected micro-structures" formed in order to adapt to the changing environment and increase their survivability as a macro-structure.[4][5][6]

Contents

Overview[edit]

The term complex adaptive systems, or complexity science, is often used to describe the loosely organized academic field that has grown up around the study of such systems. Complexity science is not a single theory—it encompasses more than one theoretical framework and is highly interdisciplinary, seeking the answers to some fundamental questions about living, adaptable, changeable systems. The study of CAS focuses on complex, emergent and macroscopic properties of the system.[6][7][8] John H. Holland said that CAS "are systems that have a large numbers of components, often called agents, that interact and adapt or learn."[9]

Typical examples of complex adaptive systems include: climate; cities; firms; markets; governments; industries; ecosystems; social networks; power grids; animal swarms; traffic flows; social insect (e.g. ant) colonies;[10] the brain and the immune system; and the cell and the developing embryo. Human social group-based endeavors, such as political parties, communities, geopolitical organizations, war, and terrorist networks are also considered CAS.[10][11][12] The internet and cyberspace—composed, collaborated, and managed by a complex mix of human–computer interactions, is also regarded as a complex adaptive system.[13][14][15] CAS can be hierarchical, but more often exhibit aspects of "self-organization."[16]

General properties[edit]

What distinguishes a CAS from a pure multi-agent system (MAS) is the focus on top-level properties and features like self-similarity, complexity, emergence and self-organization. A MAS is defined as a system composed of multiple interacting agents; whereas in CAS, the agents as well as the system are adaptive and the system is self-similar. A CAS is a complex, self-similar collectivity of interacting, adaptive agents. Complex Adaptive Systems are characterized by a high degree of adaptive capacity, giving them resilience in the face of perturbation.

Other important properties are adaptation (or homeostasis), communication, cooperation, specialization, spatial and temporal organization, and reproduction. They can be found on all levels: cells specialize, adapt and reproduce themselves just like larger organisms do. Communication and cooperation take place on all levels, from the agent to the system level. The forces driving co-operation between agents in such a system, in some cases, can be analyzed with game theory.

Characteristics[edit]

Some of the most important characteristics of complex systems are:[17]

- The number of elements is sufficiently large that conventional descriptions (e.g. a system of differential equations) are not only impractical, but cease to assist in understanding the system. Moreover, the elements interact dynamically, and the interactions can be physical or involve the exchange of information

- Such interactions are rich, i.e. any element or sub-system in the system is affected by and affects several other elements or sub-systems

- The interactions are non-linear: small changes in inputs, physical interactions or stimuli can cause large effects or very significant changes in outputs

- Interactions are primarily but not exclusively with immediate neighbours and the nature of the influence is modulated

- Any interaction can feed back onto itself directly or after a number of intervening stages. Such feedback can vary in quality. This is known as recurrency

- The overall behavior of the system of elements is not predicted by the behavior of the individual elements

- Such systems may be open and it may be difficult or impossible to define system boundaries

- Complex systems operate under far from equilibrium conditions. There has to be a constant flow of energy to maintain the organization of the system

- Complex systems have a history. They evolve and their past is co-responsible for their present behaviour

- Elements in the system may be ignorant of the behaviour of the system as a whole, responding only to the information or physical stimuli available to them locally

Robert Axelrod & Michael D. Cohen[18] identify a series of key terms from a modeling perspective:

- Strategy, a conditional action pattern that indicates what to do in which circumstances

- Artifact, a material resource that has definite location and can respond to the action of agents

- Agent, a collection of properties, strategies & capabilities for interacting with artifacts & other agents

- Population, a collection of agents, or, in some situations, collections of strategies

- System, a larger collection, including one or more populations of agents and possibly also artifacts

- Type, all the agents (or strategies) in a population that have some characteristic in common

- Variety, the diversity of types within a population or system

- Interaction pattern, the recurring regularities of contact among types within a system

- Space (physical), location in geographical space & time of agents and artifacts

- Space (conceptual), "location" in a set of categories structured so that "nearby" agents will tend to interact

- Selection, processes that lead to an increase or decrease in the frequency of various types of agent or strategies

- Success criteria or performance measures, a "score" used by an agent or designer in attributing credit in the selection of relatively successful (or unsuccessful) strategies or agents

Modeling and simulation[edit]

CAS are occasionally modeled by means of agent-based models and complex network-based models.[19] Agent-based models are developed by means of various methods and tools primarily by means of first identifying the different agents inside the model.[20] Another method of developing models for CAS involves developing complex network models by means of using interaction data of various CAS components.[21]

In 2013 SpringerOpen/BioMed Central has launched an online open-access journal on the topic of complex adaptive systems modeling (CASM).[22]

Evolution of complexity[edit]

Living organisms are complex adaptive systems. Although complexity is hard to quantify in biology, evolution has produced some remarkably complex organisms.[23] This observation has led to the common misconception of evolution being progressive and leading towards what are viewed as "higher organisms".[24]

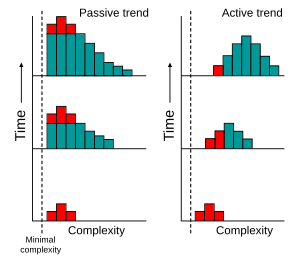

If this were generally true, evolution would possess an active trend towards complexity. As shown below, in this type of process the value of the most common amount of complexity would increase over time.[25] Indeed, some artificial life simulations have suggested that the generation of CAS is an inescapable feature of evolution.[26][27]

However, the idea of a general trend towards complexity in evolution can also be explained through a passive process.[25] This involves an increase in variance but the most common value, the mode, does not change. Thus, the maximum level of complexity increases over time, but only as an indirect product of there being more organisms in total. This type of random process is also called a bounded random walk.

In this hypothesis, the apparent trend towards more complex organisms is an illusion resulting from concentrating on the small number of large, very complex organisms that inhabit the right-hand tail of the complexity distribution and ignoring simpler and much more common organisms. This passive model emphasizes that the overwhelming majority of species are microscopic prokaryotes,[28] which comprise about half the world's biomass[29] and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity.[30] Therefore, simple life remains dominant on Earth, and complex life appears more diverse only because of sampling bias.

If there is a lack of an overall trend towards complexity in biology, this would not preclude the existence of forces driving systems towards complexity in a subset of cases. These minor trends would be balanced by other evolutionary pressures that drive systems towards less complex states.

See also[edit]

- Artificial life

- Chaos theory

- Cognitive science

- Command and Control Research Program

- Complex system

- Computational economics

- Computational sociology

- Dual-phase evolution

- Enterprise systems engineering

- Generative sciences

- Open system (systems theory)

- Santa Fe Institute

- Simulated reality

- Sociology and complexity science

- Super wicked problem

- Swarm Development Group

- Universal Darwinism

References[edit]

- ^ a b Miller, John H., and Scott E. Page (2007-01-01). Complex adaptive systems : an introduction to computational models of social life. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400835522. OCLC 760073369.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Lansing, J. Stephen (2003). "Complex Adaptive Systems". Annual Review of Anthropology. Annual Reviews. 32 (1): 183–204. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093440. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ Auerbach, David (2016-01-19). "The Theory of Everything and Then Some". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ a b "Insights from Complexity Theory: Understanding Organisations better". by Assoc. Prof. Amit Gupta, Student contributor - S. Anish, IIM Bangalore. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Ten Principles of Complexity & Enabling Infrastructures". by Professor Eve Mitleton-Kelly, Director Complexity Research Programme, London School of Economics. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Evolutionary Psychology, Complex Systems, and Social Theory" (PDF). Bruce MacLennan, Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. eecs.utk.edu. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "A Complex Adaptive Organization Under the Lens of the LIFE Model:The Case of Wikipedia". Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Complex Adaptive Systems as a Model for Evaluating Organisational : Change Caused by the Introduction of Health Information Systems" (PDF). Kieren Diment, Ping Yu, Karin Garrety, Health Informatics Research Lab, Faculty of Informatics, University of Wollongong, School of Management, University of Wollongong, NSW. uow.edu.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Holland John H (2006). "Studying Complex Adaptive Systems". Journal of Systems Science and Complexity. 19 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s11424-006-0001-z.

- ^ a b Steven Strogatz, Duncan J. Watts and Albert-László Barabási "explaining synchronicity (at 6:08), network theory, self-adaptation mechanism of complex systems, Six Degrees of separation, Small world phenomenon, events are never isolated as they depend upon each other (at 27:07) in the BBC / Discovery Documentary". BBC / Discovery. Retrieved 11 June 2012. "Unfolding the science behind the idea of six degrees of separation"

- ^ "Toward a Complex Adaptive Intelligence Community The Wiki and the Blog". D. Calvin Andrus. cia.gov. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Solvit, Samuel (2012). "Dimensions of War: Understanding War as a Complex Adaptive System". L'Harmattan. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ "The Internet Analyzed as a Complex Adaptive System". Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Cyberspace: The Ultimate Complex Adaptive System" (PDF). The International C2 Journal. Retrieved 25 August 2012. by Paul W. Phister Jr

- ^ "Complex Adaptive Systems" (PDF). mit.edu. 2001. Retrieved 25 August 2012. by Serena Chan, Research Seminar in Engineering Systems

- ^ Holland, John H. (John Henry), (1996). Hidden order : how adaptation builds complexity. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201442302. OCLC 970420200.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Paul Cilliers (1998) Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems

- ^ Robert Axelrod & Michael D. Cohen, Harnessing Complexity. Basic Books, 2001

- ^ Muaz A. K. Niazi, Towards A Novel Unified Framework for Developing Formal, Network and Validated Agent-Based Simulation Models of Complex Adaptive Systems PhD Thesis

- ^ John H. Miller & Scott E. Page, Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life, Princeton University Press Book page

- ^ Melanie Mitchell, Complexity A Guided Tour, Oxford University Press, Book page

- ^ Springer Complex Adaptive Systems Modeling Journal (CASM)

- ^ Adami C (2002). "What is complexity?". BioEssays. 24 (12): 1085–94. doi:10.1002/bies.10192. PMID 12447974.

- ^ McShea D (1991). "Complexity and evolution: What everybody knows". Biology and Philosophy. 6 (3): 303–24. doi:10.1007/BF00132234.

- ^ a b Carroll SB (2001). "Chance and necessity: the evolution of morphological complexity and diversity". Nature. 409 (6823): 1102–9. Bibcode:2001Natur.409.1102C. doi:10.1038/35059227. PMID 11234024.

- ^ Furusawa C, Kaneko K (2000). "Origin of complexity in multicellular organisms". Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (26 Pt 1): 6130–3. arXiv:nlin/0009008. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84.6130F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.6130. PMID 10991141.

- ^ Adami C, Ofria C, Collier TC (2000). "Evolution of biological complexity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (9): 4463–8. arXiv:physics/0005074. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4463A. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4463. PMC 18257. PMID 10781045.

- ^ Oren A (2004). "Prokaryote diversity and taxonomy: current status and future challenges". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359 (1444): 623–38. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1458. PMC 1693353. PMID 15253349.

- ^ Whitman W, Coleman D, Wiebe W (1998). "Prokaryotes: the unseen majority". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95 (12): 6578–83. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.6578W. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. PMC 33863. PMID 9618454.

- ^ Schloss P, Handelsman J (2004). "Status of the microbial census". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 68 (4): 686–91. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.4.686-691.2004. PMC 539005. PMID 15590780.

Literature[edit]

- Ahmed E, Elgazzar AS, Hegazi AS (28 June 2005). "An overview of complex adaptive systems". Mansoura J. Math. 32: 6059. arXiv:nlin/0506059. Bibcode:2005nlin......6059A. arXiv:nlin/0506059v1 [nlin.AO].

- Bullock S, Cliff D (2004). "Complexity and Emergent Behaviour in ICT Systems". Hewlett-Packard Labs. HP-2004-187.; commissioned as a report by the UK government's Foresight Programme.

- Dooley, K., Complexity in Social Science glossary a research training project of the European Commission.

- Edwin E. Olson; Glenda H. Eoyang (2001). Facilitating Organization Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-7879-5330-X.

- Gell-Mann, Murray (1994). The quark and the jaguar: adventures in the simple and the complex. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-2581-9.

- Holland, John H. (1992). Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: an introductory analysis with applications to biology, control, and artificial intelligence. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-58111-6.

- Holland, John H. (1999). Emergence: from chaos to order. Reading, Mass: Perseus Books. ISBN 0-7382-0142-1.

- Solvit, Samuel (2012). Dimensions of War: Understanding War as a Complex Adaptive System. Paris, France: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-99721-9.

- Kelly, Kevin (1994). Out of control: the new biology of machines, social systems and the economic world (Full text available online). Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-48340-8.

- Pharaoh, M.C. (online). Looking to systems theory for a reductive explanation of phenomenal experience and evolutionary foundations for higher order thought Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- Hobbs, George & Scheepers, Rens (2010),"Agility in Information Systems: Enabling Capabilities for the IT Function," Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems: Vol. 2: Iss. 4, Article 2. Link

- Sidney Dekker (2011). Drift into Failure: From Hunting Broken Components to Understanding Complex Systems. CRC Press.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Complex adaptive systems. |

- Complex Adaptive Systems Group loosely coupled group of scientists and software engineers interested in complex adaptive systems

- DNA Wales Research Group Current Research in Organisational change CAS/CES related news and free research data. Also linked to the Business Doctor & BBC documentary series

- A description of complex adaptive systems on the Principia Cybernetica Web.

- Quick reference single-page description of the 'world' of complexity and related ideas hosted by the Center for the Study of Complex Systems at the University of Michigan.

- Complex systems research network

- The Open Agent-Based Modeling Consortium

- TEDxRotterdam - Igor Nikolic - Complex adaptive systems, and The emergence of universal consciousness: Brendan Hughes at TEDxPretoria . Talks discussing various practical examples of complex adaptive systems, including Wikipedia, star galaxies, genetic mutation, and other examples