Béla H. Bánáthy

Béla Heinrich Bánáthy | |

|---|---|

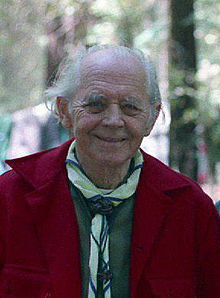

Béla H. Banathy at the 40th anniversary celebration of the White Stag program in 1998 | |

| Born | December 1, 1919 |

| Died | 4 September 2003 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | Hungarian-American |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Occupation | Educator, systems scientist, professor, author |

| Known for | Founded the White Stag Leadership Development Program, International Systems Institute, co-founder of the General Evolutionary Research Group, president of the International Federation for Systems Research from 1994-98 |

| Spouse(s) | Eva Balazs |

| Children | Béla, László (Leslie), Robert, Tibor |

Béla Heinrich Bánáthy (Hungarian: Bánáthy Béla; December 1, 1919 – September 4, 2003) was an Hungarian-American linguist, and Professor at San Jose State University and UC Berkeley. He is known as founder of the White Stag Leadership Development Program,[citation needed] established the International Systems Institute in 1982,[1] and was co-founder of the General Evolutionary Research Group in 1984.[2][3][4]

He grew up in largely rural Hungary and served in the Hungarian military during World War II. When Russia invaded Hungary in April 1945, he and his family fled to Allied-occupied Austria and lived in a displaced persons camp for six years. In 1951, they emigrated to Chicago, sponsored by the Presbyterian church. Within the year his former commanding officer suggested to the U.S. government that they hire Bánáthy as a Hungarian instructor at the Army Language School in Monterey, California. While living in Monterey, he founded the White Stag Leadership Development Program.

His program gained national attention, and the Boy Scouts of America conducted research into incorporating leadership training into its programs. The Boy Scouts of America's Wood Badge and junior leader training programs had until then focused primarily on Scoutcraft skills, not leadership. William "Green Bar Bill" Hillcourt among others resisted the change.

After 20 years, Bánáthy left the renamed Defense Language Institute and went to work for the Far West Laboratory for Research and Development in Berkeley and later San Francisco. He retired from Far West in 1989 but maintained an active interest in social systems and science, including attending many conferences and advising students and others in those fields. In 1992, he helped restart the Hungarian Scout Association within his native country. In 2003, Bánáthy and Eva moved to live with their son Tibor in Chico, California. After a brief and unexpected illness, Bánáthy died on September 4, 2003.[4]

Contents

Biography[edit]

Béla Bánáthy was born in 1919 in Gyula, Hungary, as the oldest of four sons. His father Peter was a minister of the Reformed Church in Hungary and his mother Hildegard Pallmann was a teacher.[5] Peter Bánáthy had earned the honorary title Vitéz for his service during World War I, and Béla, as his oldest son, inherited the title.[6]

Active in Scouting[edit]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

When Bánáthy was about six years old, their family informally adopted Tamas Feri. Tamas was about 13 years old and from a poor gardener's family. Tamas took Bánáthy on his first overnight camp out with his patrol to a small forest near Gyula. Bánáthy's father became the Scoutmaster of the "small scouts" troop (similar to American Cub Scouts). When Bánáthy was nine years old, he became the troop leader.[7][4]

The family moved about 84 kilometres (52 mi) from Bánáthy's birthplace of Gyula, to Makó, Hungary, about 202 kilometres (126 mi) southeast of Budapest. He joined the regular scout program of the Hungarian Scout Association and "Csanad Vezer" Troop 92. During the 1930s, the troop had more than 50 Scouts and 30 "small scouts". They held their monthly troop meetings on Sunday in a large gimnazium and met weekly every Saturday as a patrol. Bánáthy reported: "Our weekly patrol meetings focused on scoutcraft and Scout spirit and guiding us to move through the various stages of advancement in rank."[7]

The Hungarian Scout program had four stages. During the first three years, Bánáthy advanced three stages. The last stage required Bánáthy to earn 25 merit badges. This last stage was called Turul, after the mythical bird of Hungary.[7] From spring to fall, as weather permitted, the patrol had many outings. Every summer the troop went on a two- to three-week long summer camp.[7] Bánáthy and his troop attended the 4th World Scout Jamboree in 1933. Up until this time, he had intended to follow his father into the ministry, but changed his mind.[5]

Bánáthy later wrote,

The highlight of the Jamboree for me was meeting Baden Powell, the Chief Scout of the World. One day, he visited our camp with the Chief Scout of Hungary, Count Pál Teleki (who later became our Prime Minister), and the chief of the camp staff, Vitez Kisbarnaki Ferenc Farkas, a general staff officer of the Hungarian Royal Army. A few years later he became the commander of the Royal Ludovika Akademia (when I was a student there). In the 1940s, he became the Chief Scout of Hungary. (I was serving on his staff as head of national junior leadership training.)

For me the Jamboree became a crucial career decision point. I resolved to choose the military as a life work... There were two sources of this decision. One was my admiration of Lord Baden-Powell, and his life-example as a hero of the British Army and the founder and guide of scouting. The other was the influence of Captain Varkonyi, a staff officer of the Jamboree, who was assigned to our Subcamp. We spent hours in conversation about scouting and the military as a career, as a major service in the character development of young Hungarian adults. After the Jamboree we corresponded for a while. By the end of the year I shared my decision with my parents.[7]

While at the Jamboree, Bánáthy briefly met Joseph Szentkiralyi, another Scout from Hungary. Hungarian Sea Scout Paul Ferenc Sujan and American Maurice Tripp also attended. More than 20 years later, these three men collaborated in helping Bánáthy build a leadership program for youth in the United States.

Also in 1933, Bánáthy attended the regional patrol leader training week. Later in 1934, Bánáthy and six other members of his troop traveled to the National Jamboree in Poland. They camped in a large pine forest and visited Kraków and Warsaw. The Polish government hosted a banquet for all of the Scouts in the Presidential Palace.[7] In 1934, he was awarded the best notebook prize of the national spring leadership camp and in 1935, he was invited to serve on the junior staff of the same camp at Hárshegy, Budapest.[7] In 1935, the troop traveled to the Bükk Mountains in northeastern Hungary for their summer camp. As a Senior Patrol leader, Bánáthy and two others took a bicycle tour in advance of the summer camp to preview the camping site.[7]

Military service during World War II[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In 1937, Bánáthy entered the hu:Ludovika Akadémia as was the custom for young men aspiring to military careers.[5] In 1940, at age 21, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the armored infantry. Later that year he met his future wife Eva Balazs.[8] The peacetime Hungarian Army received very little training.[9] Bánáthy served two tours on the Russian front in World War II as an armored infantry officer. The Hungarian Army expanded rapidly from an initial force of 80,000, but when fighting started, the rank-and-file of the army had undergone only eight weeks of training.[9]

In 1941, Bánáthy's unit advanced as part of German Army Group South to within 140 kilometres (87 mi) of Moscow, during a severe November ice storm. In 1942, as a soldier in the 109,000 strong Second Hungarian Army (Second Magyar Honved), Bánáthy returned to the Russian front. They fought in the Battle of Voronezh at the Don River bend, supporting the German attack. They were charged with protecting the 8th Italian Army's's northern flank between the Novaya Pokrovka on the Don River to Rossosh,[10] part of the larger force defending the drive by the German 6th Army against Soviet General Vasily Chuikov's 62nd Army, which was defending Stalingrad. Bánáthy was seriously wounded during the action, and he returned from the front to Budapest where he spent seven months recuperating. He married his fiancé, Eva Balazs, with his arm in a sling on December 5, 1942 in Budapest.[5][11]

Bánáthy was promoted as a junior officer of the Royal Hungarian Army and served on the faculty of the Ludovika Akademia under his mentor, Commandant Colonel-General Kisbarnaki General Farkas. Farkas sought a volunteer to teach junior leader training at the academy and Bánáthy volunteered. Farkas also asked Bánáthy to organize a Scout Troop for young men, 19 years and older, which was a common practice within the Hungarian Scout Association at the time.[12]:133–134 Bánáthy became committed to training the young men in officer's leadership skills; he served as the voluntary national director for youth leadership development and a member of the National Council of the Hungarian Scout Association.[13]

In July 1944 Farkas was Commander of the Hungarian VI Army Corps, which had been garrisoned at Debrecen. He replaced General Beregfy, who was loyal to the fascist Arrow Cross Party. During that month, Farkas' VI Army Corp was instrumental in repelling a Red Army attack across the Carpathian mountains.[14] On 15 October 1944, Farkas was named commander of the Pest bridgehead and Government Commissioner for Evacuation.[14][15] In early November 1944, the first Russian units appeared on the southeastern edge of Budapest.[16] As an associate of Farkas, Bánáthy likely had advance notice of the Russian advance. He also knew he would likely be executed if captured. Bánáthy was able to get his wife Eva, one-year-old son Béla and two-week-old son László out of Budapest. Bánáthy's family, along with other officers and their families, found shelter at first in farmhouses, and later in bunkers, caves, and trenches.

When the Hungarian Second Army was disbanded on 1 December 1944 due to a lack of equipment and personnel, the remaining units of the Second Army, including Bánáthy's, were transferred to the Third Army. The Siege of Budapest began when the city was encircled on 29 December 1944 by the Red Army. Bánáthy fought with the remainder of his unit against the Russians until after Budapest fell on 13 February 1945. The Axis was striving to protect the last oil fields they controlled in western Hungary around Lake Balaton. By late March 1945, most of what was left of the Hungarian Third Army was surrounded and destroyed about 40 kilometres (25 mi) to the west of Budapest in an advance by the Soviet 46th Army towards Vienna.[17] The remaining shattered units fought on as they retreated progressively westward through the Transdanubian Mountains towards Austria.

Bánáthy's family and others of the remainder of his and other military units made their way west, along with tens of thousands of other refugees, about 250 kilometres (160 mi) into Austria, trying to stay ahead of advancing Russian troops. Temperatures through the time of their flight remained near 0 °C (32 °F).

Life in displaced persons camp[edit]

Bánáthy reunited with his family in Austria. As the war ended and Austria was occupied in April 1945 by the French, British, Soviet and US military forces, the family was placed in an Allied displaced persons camp. They were housed in a single 6 by 10 feet (1.8 by 3.0 m) room in a wooden barrack; it served as their bedroom, kitchen, living room and firewood storage area. Food was extremely scarce and at times they subsisted on around 600 calories per person per day.[18] They were among 1.4 million displaced persons in Austria at the time[19] during a worldwide food shortage as a result of the war. Food was also severely restricted by punitive U.S. policies including directive JCS 1067. In 1947 German citizens were surviving on 1040 calories a day, but the Allies were also suffering from food shortages.[20]

Bánáthy later traded for milk to give two-year-old Béla and one-year-old László enough protein. As extremely little food was available in the camps, in early 1947 his wife's twin sister came from Hungary to take their older two sons back to live with the older sister. The Pallendal family, Bánáthy's in-laws, was well-educated and relatively wealthy, so they had access to more food than what was available in the camps. They intended to return the Banathy boys to their parents within a year. Beginning in early 1948, when the Cold War ensued, it became virtually impossible for refugees or displaced persons to cross from the border of one country into another, or even from one Occupation Zone to another.[21][22] The Pallendal family could not return the two boys from behind the Iron Curtain.[5]

In 1948, shortly after their third son Tibor was born, the Banathy family was moved to another camp, near a Marshall Plan warehouse. Bánáthy was assigned to unload sacks of wheat from railroad cars. He contacted the World Scouting Movement for assistance and began to organize scouting in the DP camps. During 1947, Bánáthy was named the Hungarian Scout Commissioner for Austria; he led training for Hungarian Scout leaders along with his former commanding officer Farkas.[23] He was ordained by the World Council of Churches and became minister for youth among Hungarian refugees. Banathy served as director of religious education of the Protestant Refugee Service of Austria, was editor of a religious youth service and of a Scout publication.[5]

In 1948 Bánáthy's fourth son Robert was born. Bánáthy soon found work as a technical draftsman in the statistical office of a U.S. Army warehouse.[5][24][13] In 1949, with help from a Swiss foundation, Bánáthy assisted in establishing and was selected as the President of the Collegium Hungaricum, a boarding school for refugees, at Zell am See near Saalfelden, Austria.[4] In the same year, the Communist government in Hungary seized the businesses belonging to the Pallendal family. Because they were members of the social elite, the Communist government considered them to be a political threat.[25]

In 1951, in what was a common practice during this time,[26] the Hungarian Police arrived at dawn to seize the Pallendal family home and arrest and deport the family from Budapest. Seven-year-old Béla and six-year-old László Banathy, along with their Pallendal grandmother and two aunts, were put aboard a freight train and sent toward Russia. The train stopped occasionally and a few hundred people were forced off at rural towns. The Pallendal family was ejected in eastern Hungary. There an uncle located them and hid them from authorities in a small village.[citation needed]

Emigrates to the United States[edit]

In January, 1951, the student body of the Presbyterian McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago sponsored Béla, Eva, Tibor and Robert Banathy as refugees to the United States.[24] Bánáthy lived with his family at the Seminary, where he worked nights 60 hours a week shoveling coal to fire the Seminary furnace. At the same time, he was studying English from a book. He occasionally preached at nearby Hungarian churches. His wife found work as a machine operator and Tibor, their third son, entered American public school.[11]

Begins teaching Hungarian language[edit]

When World War II ended, General Farkas was designated as the U.S. Army's liaison to former Hungarian prisoners of war. In 1951 he recommended Bánáthy as a Hungarian language instructor, and Bánáthy was invited to teach at the U.S. government's Army Language School in Monterey, California.[23] Bánáthy moved to Monterey in June 1951, a pivotal change in his life. At the Army Language School, he met Joseph Szentkiralyi (Americanized as St. Clair), the founder of the Hungarian Department. They soon figured out they had met at the 4th World Scout Jamboree in 1933. The wives of the two men also realized they had been girlhood friends in grammar school in Budapest.[24] Using her experience managing the Pallendal family restaurant in Budapest before World War II, Eva took work as a waitress in a restaurant on the Monterey Peninsula. Bánáthy served as President of his local Parent-Teacher Association and on the board of the local Red Cross.[5] In the same year, Paul Ferenc Sujan, another former Hungarian scout, joined the language school faculty.[27]

On February 28, 1956, Bánáthy was naturalized as a United States citizen. After nine years of separation, and repeated failures to get his sons repatriated from behind the Iron Curtain, Bánáthy obtained help from Dr. Eugene Blake, President of the National Council of Churches; Representative Charles M. Teague; Ernest Nagy, Vice Consul in the U.S. Legation in Budapest; Hulda Neiburh of the McCormick Theological Seminary; and Howard Pyle, deputy assistant to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[28] He was finally able to arrange for 13-year-old Béla and 11-year-old László to emigrate to the United States[5] A photograph of the two boys greeting their mother was featured in Life Magazine.

Carrying pictures of their parents, two Hungarian brothers arrived at New York International Airport, Idlewild, Queens, yesterday... The pictures are necessary because the boys... have not seen their mother and father for nine years.[29]

The boys were greeted by their parents at San Francisco International Airport at 1:10 a.m. The boys' release marked the first time since the Cold War that anyone under 65 years old had been allowed to leave Hungary to be reunited with family.[28]

Professional life[edit]

Bánáthy was an educator, a systems and design scientist, and an author. At the Army Language School, he taught in the Hungarian language department, later becoming its chairman.

White Stag Leadership Development Program[edit]

In 1957 Bánáthy began enlarging a concept for a leadership development program. As Council Training Chairman in the Monterey Bay Area Council of the Boy Scouts of America, he received strong support from the Council Executive and Council Executive Board for his proposal to train boys in leadership skills. He was assisted by fellow Hungarians Joe Szentkiralyi (aka St. Clair, Chair of the Hungarian Language Department at the Army Language school) and Paul Sujan (Hungarian Language Instructor at the Army Language school); Fran Peterson (a member of the National Council and a Scoutmaster from Chular, California); and Maury Tripp (a Scouter from Saratoga, California, a member of the National Council, and a research scientist).[23][third-party source needed] "Lord Baden-Powell was my personal idol and I long felt a commitment to give back to Scouting what I had received", Bánáthy said.[24]

As part of his master's degree program in counseling psychology at San José State University, he wrote a thesis titled "A Design for Leadership Development in Scouting".[30] This book described the founding principles of the White Stag program, which was later adapted by the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America.[31] Prior to Bánáthy's work, the adult Wood Badge and the junior leader training programs had focused on teaching Scoutcraft skills and some aspects of the Patrol Method. His research and findings on teaching principles and competencies of leadership had a huge impact on these two programs, shifting their focus to leadership skills.[32][33]

Some individuals on the national staff and many volunteers across the nation resisted the idea of changing the focus of Wood Badge from training leaders in Scoutcraft to leadership skills. Among them was William "Green Bar Bill" Hillcourt, who had been the first United States Wood Badge Course Director in 1948.[34] Although officially retired, he had many loyal followers. He was adamant that Wood Badge should continue to teach Scoutcraft skills and tried to persuade the national council to stick to that tradition, but his objections were ignored.[23]

The leadership competencies Banathy articulated became the de facto method for Scout adult and junior leader training.[35] (In 2008, the White Stag program celebrated its 50th anniversary.) In 1960, the Monterey Bay Area Council recognized Béla for his exceptional service to youth and awarded him the Silver Beaver.[36]

In the 1970s, due to the success of the White Stag program, Bánáthy was appointed to the Interamerican Scout Committee and participated in three interamerican "Train the Trainer" events in Mexico, Costa Rica, and Venezuela.[5] He guided their national training teams in designing leadership development by design programs. Béla also taught in Sunday School and was on the Board of the United Methodist Church of the Wayfarer in Carmel, California.

Systems science[edit]

In the 1960s Bánáthy began teaching courses in applied linguistics and systems science at San José State University. In 1962 he was named Dean and Chairman of the East Europe and Middle East Division at the Army Language School, overseeing ten language departments. In 1963 he completed his master's degree in psychology at San Jose State University, and in 1966 he received a doctorate in education for a transdisciplinary program in education, systems theory, and linguistics from the University of California in Berkeley. During the mid-1960s Bánáthy was named Chair of Western Division of the Society for General Systems Research. He published his first book, Instructional Systems, in 1968.[4][5]

Large complex systems[edit]

During the 1960s and 1970s, Bánáthy was a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and as he continued teaching at San Jose State University. In 1969, he left the renamed Defense Language Institute and became a Program Director, and later Senior Research Director and Associate Laboratory Director, at the Far West Laboratory for Research and Development (now WestEd) in Berkeley (later moved to San Francisco). He "directed over fifty research and development programs, designed many curriculum projects and several large scale complex systems, including the design and implementation of a Ph.D. program in educational research and development for UC Berkeley".[8][5][4]

In the 1970s and 1980s, he focused his research on the application of systems and design theories and methodologies in social, social service, educational, and human development systems. In the 1980s he developed and guided a Ph.D. curriculum in humanistic systems inquiry and social systems design for the Saybrook Graduate School.[8][5][4]

International Systems Institute[edit]

In 1981, he founded the International Systems Institute[1] (ISI), a non-profit, public benefit scientific and educational corporation in Carmel, California, USA. He organized its first meeting at Fuschl am See, Austria in 1982.[1][8]

Banathy introduced a unique and never-before used approach to organizing the International Systems Institute conferences. Banathy observed that in traditional conferences, a few usually well-respected or prestigious individuals would apply to present "pre-packaged new ideas" to others. In typical conferences, presenting almost always carries more prestige than listening; the few presenters share their wisdom with the many. This one-to-many or "hierarchical knowledge distribution system" slowed the sharing and spreading of ideas about which many people cared deeply if not passionately, as there was always limited opportunity for interchange among participants. This interaction was usually wedged into the interstices of the formal schedule in the form of informal, spontaneous gatherings for which no record existed.[1]

The notion that presenting is more important than listening aroused lifelong antipathy in Bánáthy. When he formulated the leadership competencies of the White Stag Leadership Development Program in the 1960s, he described the passing of knowledge from one to another as "Manager of Learning". He wrote extensively about how the focus should be on the learner, not the teacher.[31]

Bánáthy advanced a different vision for conferences, one that would allow everyone to fully engage. He proposed that everyone be given the opportunity to prepare and distribute papers to all participants in advance of the conference. And instead of listening to speeches, conference attendees took part in extended, non-hierarchical conversations about the conference papers. The conference proceedings were the result of these conversations. Bánáthy felt strongly that systems scholars from all over the world should be given ongoing opportunities to engage in extended conversations so they might put their expertise "actively into the service of humanity worldwide".[1]

Bánáthy wrote: "We aspire to reap the 'reflecting and creating power' of groups that emerge in the course of disciplined and focused conversations on issues that are important to us and to our society". Participants at International Systems Institute gatherings have, since the original meeting organized by Bánáthy in 1982, organized them around this principle and referred to them as "conversations".[1]

General Evolutionary Research Group[edit]

In 1984, Bánáthy was co-founder with general evolution theorist Ervin László and others of the initially secret General Evolutionary Research Group, or General Evolutionary Research Group.[2] A member of the Society of General Systems Research since the 1960s, he was Managing Director of the Society in the early 1980s, and in 1985 he became its president.[1] He then served on its Board of Trustees. During the 1980s, he served on the Executive Committee of the International Federation of Systems Research.[2] In 1989, he retired from Far West Labs and returned to live on the Monterey Peninsula. He continued to serve as Professor Emeritus for the Saybrook Graduate School, counseling Ph.D. students. He also continued his work with the annual ISI international systems design conversations, and authored a number of articles and books about systems, design, and evolutionary research. He served two terms as president of the International Federation of Systems Research during 1994-98.[5]

He coordinated over twenty international systems research conferences held in eight countries, including the 1994 Conversation on Systems Design conversation held at Fuschl Am See, Austria, sponsored by the International Federation of Systems Research.[8][37] He was also honorary editor of three international systems journals: Systems Research and Behavioral Science, the Journal of Applied Systems Studies,[38] and Systems. He was on the Board of Editors of World Futures,[39] and served as a contributing editor of Educational Technology.[8]

Final years[edit]

In 1992, Bánáthy, a long-standing member of the Hungarian Scout Association Abroad (Külföldi Magyar Cserkészszövetség), traveled from his Monterey, California home in the United States to Hungary following its renewed freedom. There, he helped restart the Hungarian Scout Association within his native country.[23][third-party source needed]

Bánáthy spent considerable time during the last few years of his life caring for his wife Eva in their home in Carmel, California. She had been in poor health for a number of years after a stroke. In the summer of 2003 Bánáthy and his wife moved to live with their son Tibor in Chico, California. After a brief and unexpected illness, Bánáthy died on September 4, 2003. He and Eva had been married 64 years at the time of his death.[4]

See also[edit]

Publications[edit]

Bánáthy wrote and published several books and hundreds of articles. A selection:

- 1963, A Design for Leadership Development in Scouting, Monterey Bay Area Council, Monterey, California.

- 1964, Report on a Leadership Development Experiment, Monterey Bay Area Council, Monterey, California.

- 1968, Instructional Systems, Fearon Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8224-3930-1

- 1969, Leadership Development — World Scouting Reference Papers, No. 1, Boy Scouts World Bureau, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 1972, A Design for Foreign Language Curriculum, D.C. Heath. ISBN 978-0-669-82073-7

- 1973, Developing a Systems View of Education: The Systems Models Approach, Lear Siegler Fearon Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8224-6700-7

- 1985, with Kenneth D. Bailey et al. (ed.), Systems Inquiring: Applications, Volume II of the Proceedings of the Society for General Systems Research International Conference. Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications.

- 1991, Systems Design of Education, A Journey to Create the Future, Educational Technology, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. ISBN 978-0-87778-229-2

- 1992, A Systems View of Education: Concepts and Principles for Effective Practice, Educational Technology, Englewood Cliffs, CA. ISBN 0-87778-245-8

- 1992, "Comprehensive Systems Design in Education: Building a Design Culture," in: Education. Educational Technology, 22(3) 33–35.

- 1996, Designing Social Systems in a Changing World, Plenum, NY. ISBN 0-306-45251-0

- 1998, Evolution Guided by Design: A Systems Perspective, in Systems Research, Vol. 15.

- 1997, A Taste of Systemics, The Primer Project, 2007.

- 2000, Guided Evolution of Society: A Systems View, Springer ISBN 978-0-306-46382-2

- 2000, The Development of the AgoraWebsite: Personal Communication to Agora Stewards, International Systems Institute, Asilomar Networked Democracy Group, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 2000, Agora Structure, International Systems Institute, Asilomar Networked Democracy Group, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 2000, Bio: Personal Communication to Agora Stewards, International Systems Institute, Asilomar Networked Democracy Group, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 2000, Story: Personal Communication to Agora Stewards, International Systems Institute, Asilomar Networked Democracy Group, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 2000, Reflections: The Circle of Agora Stewards, International Systems Institute, Asilomar Networked Democracy Group, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 2000, Guided Evolution of Society: A Systems View, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York.

- 2002, with Patrick M. Jenlink, "The Agora Project: the New Agoras of the Twenty-first Century," Systems Research and Behavioral Science

- 2002, with Gordon Rowland, "Guiding our evolution: If we don't do it, who will?[permanent dead link]"

- 2005, with Patrick M. Jenlink, et al. (ed.), Dialogue as a Means of Collective Communication (Educational Linguistics), Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York. ISBN 978-0-306-48689-0

- 2007, with Patrick M. Jenlink, et al. (ed.), Dialogue as a Means of Collective Communication (Volume 2), Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York. ISBN 978-0-387-75842-8

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Tad Goguen Frantz, "The ISI Story Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine," 1995; (Re)published at systemsinstitute.com, September 28, 2008. Accessed 26-03-2017.

- ^ a b c "The General Evolution Research Group". Archived from the original on 2016-10-08. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Bela H. Banathy. A Systems View of Education, 1992. p. 207

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Bela H. Bánáthy Obituary". www.whitestag.org. Chico Chico Enterprise Record. October 3, 2003. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jenlink, Patrick M. (August 2004). "A Biography of Béla H. Banathy: A Systems Scholar" (pdf). Systemic Practice and Action Research. 17 (4): 253–263. doi:10.1023/B:SPAA.0000040646.93483.22. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ "Dr vitéz Bánáthy Péter" (in Hungarian). Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lew Orans (1996-12-14). "Béla's Story: Scouting in Hungary, 1925-1937". Archived from the original on February 28, 2003. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Bánáthy, Béla H. & IFSR Staff (1994). "Béla H. Banathy". IFSR Newsletter. Vienna, AUT: International Federation for Systems Research. 13 (2, July [no. 33]). Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ a b Mollo, Andrew; McGregor, Malcolm; Turner, Pierre (1981). The Armed Forces of World War II: Uniforms, Insignia, and Organization. New York, N.Y.: Crown Publishers. p. 207. ISBN 0-517-54478-4.

- ^ Haupt, Army Group South. p. 199

- ^ a b "Petition for Naturalization, Number 122420". California, Federal Naturalization Records, 1843-1999 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA.

- ^ Balázs Ablonczy (2006). Pál Teleki (1879-1941)-The Life of a Controversial Hungarian Politician. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-88033-595-9.

- ^ a b Béla H. Bánáthy Sr. (May 1969). "C. V. Béla H. Bánáthy, Sr., Ed.D." Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ a b "Was Kisbarnaki Farkas a war criminal? Historikerstreit". 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Kadar, Gabor & Zoltan Vagi. Self-Financing Genocide: The Gold Train - The Becher Case - The Wealth of Jews, Hungary. Central European University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-963-9241-53-4.

- ^ Ungváry, Krisztián (2005). The siege of Budapest: 100 Days in World War II. Ladislaus Löb, trans.; forward by John Lukacs. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. xvii. ISBN 978-0-300-10468-4.

- ^ Dollinger, Hans. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. p 199. ISBN 978-0-517-12399-7

- ^ Noyes, Arthur A. (March 7, 1946). "Austrian Food Must Be Cut, UNRRA Says". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "The Early Occupation Period". 2001-09-23. Archived from the original on 2009-12-05. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ^ Dietrich, John (2002). The Morgenthau Plan: Soviet Influence on American Postwar Policy. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 1-892941-90-2.

- ^ "Eva Banathy Obituary". Brusie Funeral Home. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ Borbas, K. (May–June 2005). "Current Events". Hadak Utjan. Translated by L.B.G. Simonyi. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ a b c d e St. Clair, Joe; Miyamoto, Alan; Peterson. "White Stag History Since 1933". Archived from the original on 2008-09-20. Retrieved 2008-10-22.[third-party source needed]

- ^ a b c d Helene H. Parsons (1977-09-04). "Special Leadership Camps Held at Pico Blanco". Monterey Peninsula Herald.

- ^ "Prelude to Revolution: Deconstructing Society in Hungary, 1949-1953". 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ John Lukacs (1994). Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and Its Culture. Grove Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-8021-3250-5.

- ^ "Founders: "Uncle" Paul Sujan". www.whitestag.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Iron Curtain Parted, Sons Join Parents in Monterey after Nine-year Separation". Monterey Peninsula Herald. 1956-09-17.

- ^ "2 Boys on Long Voyage". New York Times. 1956-09-17. Retrieved 2008-10-12. (Subscription required (help)). Archived article requires payment for access.

- ^ Béla Bánáthy (1963). A Design for Leadership Development in Scouting. Monterey Bay Area Council.

- ^ a b Béla Banathy (1964). Report on a Leadership Development Experiment. Monterey Bay Area Council.

- ^ Mike Barnard (2002). "History of Wood Badge in the United States". Wood Badge.org. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ A History of Wood Badge in the United States. Boy Scouts of America. 1990. ASIN B0013ENRE8.

- ^ Mike Barnard (2001). "Green Bar Bill Hillcourt's Impact on Wood Badge". Wood Badge.org. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ Troop Leader Development Staff Guide. Boy Scouts of America. 1974. pp. 94–95.

- ^ Jim, Himlyn. "Image History of the Monterey Bay Area Council Silver Beaver Recipients". Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ "Fuschl Conversations Archived 2008-10-17 at the Wayback Machine." International Federation for Systems Research. November 25, 2007. Retrieved on December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Journal of Applied Systems Studies, Editorial Board Archived 2009-03-31 at the Wayback Machine." Journal of Applied Systems Studies Archived 2008-12-08 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on December 15, 2008.

- ^ World Futures Archived 2011-12-22 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on December 15, 2008

Further reading[edit]

- Bánáthy, Béla H. & IFSR Staff (1994). "Béla H. Banathy". IFSR Newsletter. Vienna, AUT: International Federation for Systems Research. 13 (2, July [no. 33]). Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Gordon Dyer, "Y3K: Beyond Systems Design as we know it", in: Res-Systemica, Vol. 2, 2002.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Béla H. Bánáthy |

- Autobiography: Béla H. Banathy, at White Stag Leadership Development, 4 September 2003.

- "Guides and Teachers: Béla H. Banathy", Evolve

- 1919 births

- 2003 deaths

- People from Gyula

- Systems thinking

- People associated with the Boy Scouts of America

- Social systems

- Systems theory

- Systems scientists

- Language teachers

- San Jose State University alumni

- San Jose State University faculty

- University of California, Berkeley faculty

- Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- Defense Language Institute faculty

- People from Carmel-by-the-Sea, California