1922 British Mount Everest expedition

The 1922 British Mount Everest expedition was the first mountaineering expedition with the express aim of making the first ascent of Mount Everest. This was also the first expedition that attempted to climb Everest using bottled oxygen. The expedition would attempt to climb Everest from the northern side out of Tibet. At the time, Everest could not be attempted from the south out of Nepal as the country was closed to Western foreigners.

The 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition had seen the whole eastern and northern surroundings of the mountain. In searching for the easiest route, George Mallory, who was also a participant of the 1924 expedition (and the only person on all three expeditions in 1921, 1922 and 1924), had discovered a route which, according to his opinion, would allow an attempt on the summit.

After two unsuccessful summit attempts the expedition ended on the third attempt when seven porters died as the result of a group-induced avalanche. Not only had the expedition failed to reach the summit but it also marked the first reported climbing deaths on Mount Everest. The expedition did however establish a new world record climbing height of 8,326 metres (27,320 ft) during their second summit attempt, which was subsequently exceeded in the 1924 expedition.

Contents

Preparations[edit]

The attempted ascent was – notwithstanding other aims – an expression of the pioneering thinking that was common in the British Empire. As the British were unsuccessful as the first to reach the North and South Poles they tried to go to the so-called "third pole" – to "conquer" Mount Everest.

Cecil Rawling had planned three expeditions in 1915 and 1916 but they never happened due to the outbreak of the First World War and his death in 1917. The expeditions in the 1920s were planned and managed by the British Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club in a joint Mount Everest Committee.[1]

The surveying activities in 1921 allowed the creation of maps which were a pre-condition for the 1922 expedition. John Noel took on the role of official expedition photographer. He took with him three movie cameras, two panorama cameras, four sheet cameras, one stereo camera and five so called "vest pocket Kodaks". The last named were small cameras that were of light weight and size to be taken by the mountaineers to great heights. These cameras were intended to allow climbers to document a possible summit success. Additionally they had on their way a special "black tent" for photographic works. Thanks to Noel's efforts, many photographs and one movie chronicled the expedition.[2]

During the 1921 expedition they had seen that the best time for a summit bid would be April–May before the monsoon season. The expeditions in 1922 and 1924 were planned according to this knowledge.

Bottled oxygen as a mountaineering aid[edit]

This year of 1922 can also be seen as the starting year for the enduring question of "fair means" and controversies about the use of bottled oxygen for mountaineering purposes in the "death zone". Alexander Mitchell Kellas was one of the very first scientist who had pointed out the possible use of bottled oxygen for gaining great heights. At this point in time the available systems (derived from mining rescue systems) were in his opinion too heavy to be a help at great heights. Kellas was part of the Everest reconnaissance expedition in 1921 but died on the way to Mt. Everest. This expedition had taken bottled oxygen with them, but it was never used. Additionally, few paid much attention to Kellas' innovative ideas, possibly because his scientific work belonged strictly to the amateur tradition. More attention was paid to the pressure vessel experiments of Professor Georges Dreyer, who had studied high-altitude problems the Royal Air Force encountered in World War I. According to his experiments—which he did partly together with George Ingle Finch—survival at great heights could only be possible with the aid of additional oxygen.

As a consequence of this scientific work, the 1922 expedition planned to use bottled oxygen. One bottle contained ca. 240 litres of oxygen. Four bottles were fixed on a carrying frame which had to be carried by the mountaineer. With the additional elements there was a weight of ca. 14.5 kg., so every mountaineer at the beginning of a climbing day had to bear a very heavy additional load. Ten of these systems were part of the expedition equipment. As well as a mask over mouth and nose, a tube was held in the mouth. Dreyer also had proposed the flow of oxygen: at 7,000 m (22,970 ft) a flow rate of 2 litres of oxygen per minute, on the summit climb they should use 2.4 litres per minute.[3] The result was a usable time of two hours per bottle. So all the oxygen would be used up after a maximum of 8 hours of climbing. Nowadays, 3 or 4-litre bottles are filled with oxygen of 250 bar pressure. At a flow of 2 litres per minute a modern bottle can be used for about 6 hours.[4]

George Finch was responsible for this equipment during this expedition which also was related to his education as a chemist and to his knowledge of this very technique. He ordered daily training for his climber colleagues to become accustomed in the use of this equipment. The apparatuses were very often faulty, were of low robustness and were very heavy together with a low grade of oxygen filling. There was unhappiness about these bottles among the mountaineers; many intended to climb without use of these bottles.[2][3] The Tibetan and Nepalese porters nicknamed these oxygen bottles as "English air".

Expedition participants[edit]

The expedition participants were selected not just for their mountaineering qualifications: family background as well as their military experiences and professions were highly valued.[1][2]

| Name | Function | Profession |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce

expedition leader |

Soldier (Officer, rank: Brigadier) | |

| Edward Lisle Strutt | Deputy expedition leader and mountaineer | Soldier (Officer, rank: Lieutenant Colonel) |

| George Mallory | Mountaineer | Teacher |

| George Ingle Finch | Mountaineer | Chemist (Imperial College London) |

| Edward "Teddy" F. Norton | Mountaineer | Soldier (Officer, rank: Major) |

| Henry T. Morshead | Mountaineer | Soldier (Officer, rank: Major) |

| Dr Howard Somervell | Mountaineer | medicine |

| Dr Arthur Wakefield | Mountaineer | medicine |

| John Noel | Photographer and movie maker | Soldier (Officer, rank: Captain) |

| Dr Tom G. Longstaff | Expedition medicine | medicine |

| Geoffrey Bruce (cousin of Charles G. Bruce) | translator and organisational tasks | Soldier (Officer, rank: Captain) |

| C. John Morris | translator and organisational tasks | Soldier (Officer, rank: Captain) |

| Colin G. Crawford | translator and organisational tasks | officer of the British civil colonial government |

The mountaineers were accompanied by a large group of Tibetan and Nepalese porters so that the expedition in the end counted 160 men.

Approach to Mount Everest[edit]

The journey to base camp primarily followed the route used in 1921. Starting in India, the expedition members gathered in Darjeeling at the end of March 1922. Some participants had arrived one month earlier to organise and recruit porters. The journey started on 26 March for most participants. Crawford and Finch stayed a couple more days to organise transportation for the oxygen systems. These items had arrived too late in Kolkata when the main travel started in Darjeeling. This further organisation went well and further transportation of the bottles was without incident.

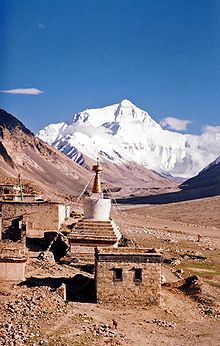

For the journey through Tibet they had a travel permit from the Dalai Lama. From Darjeeling the route went to Kalimpong, then Phari Dzong and further to Kampa Dzong which they reached on 11 April. Here the group rested for three days so that Finch and Crawford could catch up to the team with the oxygen bottles. Then they went to Shelkar Dzong, then north to the Rongbuk Monastery and to the spot where they wanted to erect base camp. To promote the process of acclimatisation the participants alternated their travelling methods between walking and horse riding. On 1 May, they reached the lower end of the Rongbuk Glacier, the site of base camp.[5]

Planned climbing route[edit]

For the British expeditions before World War II, Everest was only climbable from the north out of Tibet as the southern side in Nepal was closed to Western foreigners at the time. Mallory had discovered a "makeable" route in 1921 from the Lhakpa La to the north face of the mountain and further to the summit. This route begins at the Rongbuk Glacier, then leads through the rough valley of the eastern Rongbuk Glacier and then to the icy eastern slopes of the North Col. From there the exposed ridges of North Ridge and Northeast Ridge allow an access in direction of the summit pyramid. A severe climbing hindrance, at the time an unknown obstacle, was the so-called Second Step at 8,605 m (28,230 ft), one of three breaks in slope on the upper northeast ridge. This step is approximately 30 m high and has a slope of more than 70 degrees, with a final wall of nearly seven vertical metres. From there the ridge route leads to the summit, by lengthy but gentle slopes. (The first official successful climb on this route was the Chinese ascent of 1960.)[6] Alternatively the British checked a route via the north wall flanks of the mountain and to ascend by the later so called Norton Couloir to the Third Step and to the summit. (This route was used by Reinhold Messner on his first solo ascent in 1980.)

Summit attempts[edit]

The base camp area in the Rongbuk Valley as well as the upper east Rongbuk Glacier were known from the 1921 reconnaissance expedition but nobody had yet gone along the eastern Rongbuk Glacier valley. So on 5 May, Strutt, Longstaff, Morshead and Norton tried a first intensive reconnaissance of this valley. The Advanced Base Camp (ABC) was erected on the upper end of the glacier below icy slopes of the North Col at 6,400 m (21,000 ft). Between the base camp and the advanced base camp they erected two intermediate camps: camp I at 5,400 m (17,720 ft) and Camp II at 6,000 m (19,690 ft). The erection and the feeding of these camps was supported by local farmers who only could help for a short time as their own farms needed work.[5] Longstaff became exhausted in managing the organisation and transporting tasks and became so ill that he could not do any real mountaineering activities later on in the expedition.[2]

On 10 May Mallory and Somervell left base camp to erect Camp IV on the North Col. They arrived in Camp II only two and a half hours later. On 11 May they started to climb on the North Col.[5] This camp was at a height of 7000 m and was supported with food. The further plan was to do a first ascent trial by Mallory and Somervell without supplemental oxygen, then followed by a second climb by Finch and Norton with oxygen. However, these plans failed as a majority of the climbers became ill. So it was decided that the (more or less) healthy climbers Mallory, Somervell, Norton and Morshead should climb together.[2]

First: Without oxygen[edit]

This first attempt was made by Mallory, Somervell, Norton and Morshead without oxygen, and was supported by nine porters. They started 19 May from Camp III. They climbed at 8:45 a.m. to the North Col. The day was nice and sunny according to Mallory. Around 1 p.m. they erected the tents. The following day the climbers intended to carry only the minimum stuff: two of the smallest tents, two double sleeping bags, food for 36 hours, a gas cooking system and two thermos bottles for drinks. The porters were with three persons per tent and they were in good health at this point in time.

The following day, 20 May, Mallory was awake around 5:30 a.m. and inspired the group to start the day. The porters had slept badly the night before, as the tents provided inadequate air flow and let little oxygen into them. Only five of them intended to go up higher on the mountain. As there were also problems in preparing the food they started the further climb around 7 a.m. However, the weather worsened and the temperature fell dramatically. Above the North Col they climbed on unknown territory. Never before had any mountaineer climbed on the summit slopes of such a mountain. The porters had no warm clothing and shivered excessively. As the effort required to cut steps into the icy slopes was severe because of the hard ice surface they dropped their plan to erect a camp at 8,200 m (26,900 ft). They only went to 7600 m (which is common also for today) and erected a small camp which was named Camp V. Somervell and Morshead could erect their tent quite upright but Mallory and Norton had to use an uncomfortable slope some 50 metres away. The porters were sent down the mountain.

On 21 May the four mountaineers left their sleeping bags around 6:30 a.m. and were ready to go around 8 am. During preparation a rucksack with food fell down the mountain. Morshead, who had to fight the cold, was able to regain this rucksack but he was so exhausted from this action that he could not go higher. The climb of Mallory, Somervell and Norton was along the north ridge in direction of the upper northeast ridge. The circumstances were not ideal ones as a light snowfall began to cover the mountain. According to Mallory the snow ramps were not hard to climb. Shortly after 2 p.m. the mountaineers decided to turn around. They were 150 m below the ridge. The gained height was 8,225 m (26,985 ft) which was a world record in climbing. Around 4 p.m. they got back to Morshead in the last camp and climbed down with him. There was nearly an accident as all mountaineers except Mallory began to slip. However, Mallory was able to hold them by his rope and ice axe. They got back to Camp V in the dark and crossed a dangerous area of crevasses above the camp. On 22 May they started to climb down from North Col at 6 am.[5]

Second: With oxygen[edit]

| green line | normal route, mainly the route tried in 1922, high camps ca. 7700 and 8300 m, nowadays the 8300 camp is a little to the west (marked with 2 triangles) |

| red line | Great Couloir or Norton Couloir |

| dark blue line | Hornbein Couloir |

| ? | 2nd step at 8605m, ca. 30m, class 5–9 |

| a) | spot at ca. 8325m where George Finch went with bottled oxygen |

The second climb was done by George Ingle Finch, Geoffrey Bruce and the Gurkha officer Tejbir with oxygen support. After Finch had regained his health he stated that no real mountaineer even of lesser ability was available, so searched for others fit enough to climb. Bruce and Tejbir seemed to be qualified next. In the days before the oxygen bottles had been transported to Camp III so that enough bottles were available on the upper slopes. The three mountaineers went to camp III on 20 May, checked the bottles and found them in a good state.

On 24 May they climbed to the North Col together with Noel. There Finch, Bruce and Tejbir began at 8 a.m. the following day to climb via the north ridge and on to the northeast ridge. The extreme wind was quite a hindrance the entire climb. Twelve porters transported the bottles and the other equipment. In doing this again it was evident that the use of oxygen was a great help. The three mountaineers could climb much faster than the porters despite their heavier loads. As the wind grew intense they erected camp at 7,460 m (24,480 ft). The following day 26 May the weather worsened and the group could climb no further.

They again climbed on 27 May. At this point the food was nearly exhausted as such a long lasting climb had not been planned. Nevertheless, they started at 6:30 a.m with the sun shining but climbing was hindered by a steadily increasing wind. Tejbir who had no suitable clothing against the wind grew slow and slower and broke down at 7,925 m (26,000 ft). Finch and Bruce sent him back to the camp and again climbed to the northeast ridge but they were no longer roped together. At 7,950 m (26,080 ft) Finch changed the route because of the severe wind conditions and they entered the north wall flank in the direction of the steep couloir later named "Norton Couloir". They made good progress horizontally but they gained no further elevation. At 8326 m Bruce had a problem with the oxygen system. Finch determined that Bruce was exhausted and so they turned back. During this climb the height record was broken again. At 4 p.m. the mountaineers got back to the Camp on the North Col, and 1½ hours later they were back at Camp III on the upper Eastern Rongbuk Glacier.[5]

Third: Avalanche kills 7[edit]

In the medical opinion of Longstaff, they should not have made a third try, as all mountaineers were exhausted or ill. However, Somervell and Wakefield saw no big risks, and a third try was undertaken.

On 3 June Mallory, Somervell, Finch, Wakefield and Crawford started with 14 porters at base camp. Finch had to quit in Camp I. The others arrived in Camp III on 5 June and spent one day there. Mallory had been impressed by the power of Finch, who in the second attempt had climbed much higher in the direction of the summit and also was nearer to the summit in horizontal distance. Mallory now also wanted to use oxygen.[2]

On 7 June Mallory, Somervell and Crawford led the porters through the icy slopes of North Col. The 17 men were divided into four groups, each one roped together. The European mountaineers were in the first group and compacted the snow. Half way a piece of snow became loose. Mallory, Somervell and Crawford were partially buried under snow but managed to free themselves. The group behind them was hit by an avalanche of 30 m of heavy snow, and the other nine porters in two groups fell into a crevasse and were buried under huge masses of snow. Two porters were dug out of the snow, six other porters were dead, and one porter could not be retrieved dead or alive. This accident was the end of the climbing and marked the end of this expedition.[7] Mallory had made a mistake attempting to go straight up on the icy slopes of the glacier instead of trying lesser slopes in curves. As a result, the climbers triggered an avalanche.

On 2 August all the European expedition members were back in Darjeeling.[8]

After the expedition[edit]

After their journey back to England Mallory and Finch toured the country making presentations on the expedition. This tour had two goals. First, interested audiences would get information on the expedition and the results. Second, with the financial results of this journey another expedition should be financed. Mallory additionally made a three-month trip to the United States. During this travel Mallory was asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest. His answer: "Because it is there" became a classic.[9] The intended 1923 expedition to Mount Everest was delayed by financial and organizational reasons. There was insufficient time to prepare another expedition the following year.

The movie which was recorded by Noel during this expedition was also published. Climbing Mount Everest was shown for ten weeks in Liverpool's Philharmonic Hall.[2]

The European expedition members received the Olympic medal in alpinism at the 1924 Summer Olympic Games. To each of the 13 participants Pierre de Coubertin presented a Silver Medal with gold overlay.[10]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Breashears, David; Salkeld, Audrey (2000). Mallorys Geheimnis. Was geschah am Mount Everest? (in German). Steiger. ISBN 3-89652-220-5.

- Holzel, Tom; Salkeld, Audrey (1999). In der Todeszone. Das Geheimnis um George Mallory und die Erstbesteigung des Mount Everest (in German). Goldmann Wilhelm GmbH. ISBN 3-442-15076-0.

- West, John B. (May 2003). "George I. Finch and his pioneering use of oxygen for climbing at extreme altitudes". Journal of Applied Physiology. American Physiological Society. 94 (5): 1702–1713. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00950.2002. PMID 12679344. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Holzel, Salkeld: In der Todeszone

- ^ a b c d e f g Breashers, Salkeld: Mallorys Geheimnis

- ^ a b West, John; Journal of Applied Physiology

- ^ Bielefeldt, H. "The use of bottled oxygen" (in German). Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e The Geographical Journal, Nr.6, 1922

- ^ "Everest Summits in the 1960s". Everest History. EverestNews.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ The Geographical Journal, Nr.2, 1922

- ^ Die Naturwissenschaften, Nr. 5, 1923

- ^ Hazards of the Alps The New York Times, 18 March 1923

- ^ "Olympic Art Competition 1924 Paris". Olympic Museum. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.