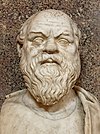

De genio Socratis

De genio Socratis (Greek: Περί του Σωκράτους δαιμονίου Perí tou Sōkrátous daimoníou) is a work by Plutarch, part of his collection of works entitled Moralia.

Contents

Title[edit]

The title refers to the daimon of Socrates; as the Latin equivalent of this term is genius, it is often rendered as On the Genius of Socrates. The word genius in this usage pertains to a vital energy (c.f. - élan vital) or spirit (spiritus) or nature of something.[1][2][3][4][5]

Contents[edit]

The progress of discussion specifically on the subject of Socrates-daimon is instigated by the description of an occurrence pertaining subjectively to this (i.e. the daimon vis-a-vis Socrates). The text begins with the words an Italian Pythagorean is waiting at a grave for a divine sign, by which the reader understands this to have the meaning; an individual waiting at a grave for a daimonion.[6]

Pertinently, Sophroniscus was cautioned by someone, and thus perhaps imbued to stem his influence on Socrates as to his work (ergon), because he had been told of his son (Socrates) having a guardian spirit who would lead him in the best way (the right way), according to the text.[7]

Responses[edit]

The myth of Timarchus of Chaeronea within the piece is thought to be an imitation of Plato's Myth of Er (a part of the larger work, known as the Republic).[4][8]

It is noted (see ref.) that De genio Socratis is similar to Phaedo by Plato, in at least due to the fact that both works are concerned especially with the divine sign, that is the daimon, of Socrates.[9]

Plutarch identified the daimon with the conscience.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ De Genio Socratis by Plutarch [Retrieved 2015-04-24](verification)

- ^ Plutarch, (DA Russell - translator) - On the Daimonion of Socrates: Human Liberation, Divine Guidance and Philosophy Volume 16 of SAPERE. Scripta antiquitatis posterioris ad ethicam religionemque pertinentia Mohr Siebeck, 2010 ISBN 3161501373 [Retrieved 2015-04-24](first source)

- ^ D Summers - The Judgment of Sense: Renaissance Naturalism and the Rise of Aesthetics (p.122) Volume 5 of Ideas in Context, Cambridge University Press, 23 Feb 1990 (reprint, revised) ISBN 0521386314 [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

- ^ a b P. Th. M. G. Liebregts. Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism (p.122). Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 2004. ISBN 0838640117. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ Joseph Baretti - Dizionario Italiano, Ed Inglese Di Giuseppe Baretti: 2 (An English and Italian dictionary) (p.314) Published - Florence 1816 for John Marenigh [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

- ^ JR. Levison (1997). The Spirit in First-Century Judaism (p.12). BRILL. ISBN 0391041312. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ Xenophon (Translated by Sir William Smith, Connop Thirlwall, George Bomford Wheeler), Raphael Kühner, Gustav Friedrich Wiggers, Friedrich Schleiermacher - Xenophon's Memorabilia of Socrates: With English Notes, Critical and Explanatory, the Prolegomena of Kühner, Wiggers' Life of Socrates, Etc (p.374) Harper & brothers, 1848 [Retrieved 2015-04-30]

- ^ JD Turner - Sethian Gnosticism and the Platonic Tradition Presses Université Laval, 2001 ISBN 2763778348 [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

- ^ DA Stoike - Plutarch's Theological Writings and Early Christian Literature (p.237) Volume 3 of Studia Ad Corpus Hellenisticum Novi Testamenti, No 3 (edited by H Dieter Betz) BRILL, 1975 ISBN 9004039856 [Retrieved 2015-04-24]

- ^ Henry Chadwick - Studies on Ancient Christianity (p.15) Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006 ISBN 0860789764 [Retrieved 2015-04-24]