Lysis (dialogue)

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

Lysis (/ˈlaɪsɪs/; Greek: Λύσις, genitive case Λύσιδος, showing the stem Λύσιδ-, from which the infrequent translation Lysides), is a dialogue of Plato which discusses the nature of friendship. It is generally classified as an early dialogue.

The main characters are Socrates, the boys Lysis and Menexenus who are friends, as well as Hippothales, who is in unrequited love with Lysis and therefore, after the initial conversation, hides himself behind the surrounding listeners. Socrates proposes four possible notions regarding the true nature of friendship:

- Friendship between people who are similar, interpreted by Socrates as friendship between good men.

- Friendship between men who are dissimilar.

- Friendship between men who are neither good nor bad and good men.

- Gradually emerging: friendship between those who are relatives (οἰκεῖοι "not kindred") by the nature of their souls.

Of all those options, Socrates thinks that the only logical possibility is the friendship between men who are good and men who are neither good nor bad.

In the end, Socrates seems to discard all these ideas as wrong, although his para-logical refutations have strong hints of irony about them.

Contents

- 1 Characters

- 2 Summary

- 2.1 Depiction of simple eros (sexual love) and philia (friendship) [203a–207d]

- 2.2 Knowledge is the source of happiness [207d–210e]

- 2.3 Reciprocal and non-reciprocal friendship [211a–213d]

- 2.4 Like is friend to like [213e–215c]

- 2.5 Unlike is friend to unlike [215c–216b]

- 2.6 The presence of bad is the cause of love (philia) [216c–218c]

- 2.7 The possession of good is the goal of love (philia) [216d–219b]

- 2.8 The first thing that is loved [219c–220e]

- 2.9 Desire is the cause of love [221a–221d]

- 2.10 What is akin is friend to what is akin: aporia [159e–223a]

- 3 In popular culture

- 4 Greek text

- 5 Translations

- 6 Secondary literature

- 7 External links

Characters[edit]

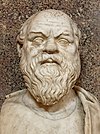

- Socrates

- Ctesippus - Cousin of Menexenus. Also appears in the Euthydemus.

- Hippothales - Of approximately the same age of Ctesippus.

- Lysis - Eldest son of Democrates I of Aexone, in his early teens.

- Menexenus - Son of Demophon, of the same age as Lysis. Probable namesake of the Menexenus.

Summary[edit]

Depiction of simple eros (sexual love) and philia (friendship) [203a–207d][edit]

Hippothales is accused by Ctesippus, that he still presents annoying praises of his beloved person before the others. He is then asked by Socrates to show his usual behavior in this situation. He admits his love for Lysis, but refuses, that he behaves by the manner depicted by the others. According to Ctesippus it is possible only by his absolute madness, because how would the others know about the love otherwise?

Hippothales composes verses on his own honor[edit]

The victory is a real gain of such love, about which Hippothales sings. He is aroused by denied access to such love and encourages only himself in a fear from possible difficulties.

The perspective of possible future relationship is spoiled[edit]

The beloved person, who otherwise has not lost his self-criticism, can be conquered by his own pride. The lack of wit, surplus of emotions in behavior, does not create reverence and respect and makes impossible to conquer somebody, gaining his sympathy. The one, who should rule in the measure which makes him a part of the relationship, instead of it hurts himself.

The following Socrates' dialogue with Lysis implies, that loved by his parents he on the other hand is limited in the most of that what he would wish. Lysis is forced to let the others decide about him (compare with a rental coachman when he is carrying his family). His abilities are not subject of a blind faith.

The conclusion is, that friendship must be the opposite of hypocrisy, which sometimes emerges from the surplus of flattering...

Knowledge is the source of happiness [207d–210e][edit]

Another important conclusion from the dialogue with Lysis is that, although his parents wish his complete happiness, they forbid him to do anything about which he has insufficient knowledge. He is allowed to do something only when his parents are sure that he can do it successfully. He is able to please his parents and make them happy when he is better at doing something than other boys are.

Reciprocal and non-reciprocal friendship [211a–213d][edit]

The dialogue continues with Lysis only as a listener. Socrates is trying to find out what is friendship. He claims, that friendship is always reciprocal. The friendship of the lover is sufficient to it. But he can obtain back even the hatred. And it is not true, that the one who is hated or who perhaps hates is a friend. That is in contradiction with the mentioned thesis, that friendship is reciprocal. The opposite must be true then. Friendship is non-reciprocal. Otherwise the lover cannot be happy. For example, of his child, which does not obey him and even hate him. The conclusion is that people are loved by their enemies (parents) and hated by their friends (children). Then it is not valid every time, that lover has in loved his friend. This is in contradiction with the premise saying, that friendship can be non-reciprocal.

Like is friend to like [213e–215c][edit]

Bad men do not tend neither towards other bad men nor the good ones. The former can be harmful and the latter would probably refuse the disharmony. On the other hand, the good men can have only no differences to be good and have therefore no profit from each other. They are perfect and can be in love only to the extent to which they feel insufficiency, therefore to no extent.

Unlike is friend to unlike [215c–216b][edit]

The opposites attracts one another. For example, the full needs the empty and empty needs the full. But this is not right in the case of human beings. For example, good vs. evil, just vs. unjust...

The presence of bad is the cause of love (philia) [216c–218c][edit]

Searching continues in an attempt to determine the first principle of friendship. The friendship must consists only in itself. Perhaps it is the good itself. But it would not be for itself the everything unless the evil is present.

The possession of good is the goal of love (philia) [216d–219b][edit]

The friendship must not lead us to something else (like to the evil). Must be itself only thanks to its own opposite. The opposite is therefore not only bad, but also useful. But there are situations, in which can be viewed the opposite for example of the good — like hunger or thirst — with disgrace. It is possible that even in not presence of the opposite, the elements of friendship can somewhere exist, which is in contradiction with that, that they consist in their opposite. The possession of the good by definition of friendship is therefore retained along for a while.

The first thing that is loved [219c–220e][edit]

So far it was successful to grasp only a shadow of the real nature of friendship. We tend to the good to escape the evil, to the health to escape the illness, to the certain friend (doctor) to escape the enemy. We do not know the first thing, that is loved.

Desire is the cause of love [221a–221d][edit]

The friendship can have another reason, than a way to the good (escaping the evil). It can be desire, longing for a something. By such way is responded to insufficiency, to our limitation in something. Insufficiency is that which makes us to be close each other. The friendship is therefore something inevitable for us. We are loved by something, we cannot be without it, which we ask by our nature. It is therefore impossible to distinguish object of friendship from us.

What is akin is friend to what is akin: aporia [159e–223a][edit]

An attempt is possible to distinguish the insufficiency from the mere unlikeness. The evil is insufficiency for everything, the good the sufficiency. For themselves are good and evil alike sufficient; however, they cannot be friends the ones who are akin to themselves. From the point of view of the first principle of friendship the distinguishing the insufficiency from the unlikeness was not successful.

In popular culture[edit]

- French aristocrat Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen, who had fled Paris in the early 1900s after a homosexual scandal, named the house he built on Capri Villa Lysis after the title of this dialogue.

- British author Mary Renault used the character of Lysis as a major character in her novel The Last of the Wine which follows the relationship between two students of Socrates. In this novel, Lysis is also the son of Demokrates.

Greek text[edit]

- Platonis opera, ed. John Burnet, Tom. III, Oxford 1903

Translations[edit]

- Thomas Taylor, 1804

- Benjamin Jowett, 1892: full text

- J. Wright, 1921

- W. R. M. Lamb, 1925: full text

- David Bolotin, 1979

- Stanley Lombardo, 1997

- T. Penner & C. Rowe (In Plato's Lysis, CUP 2005, pp. 326-351.)

Secondary literature[edit]

- David Bolotin, Plato’s dialogue on Friendship. An Interpretation of the Lysis with a new translation, Ithaca/London 1979

- C. P. Seech, Platos’s Lysis as Drama and Philosophy, Diss. San Diego 1979

- Michael Bordt: Platon, Lysis. Übersetzung und Kommentar, Göttingen 1998.

- Hans Krämer/Maria Lualdi: Platone.Liside, Milano 1998. (Greek text with an Italian translation, introduction and comment).

- Horst Peters: Platons Dialog Lysis. Ein unlösbares Rätsel? Frankfurt a. Main 2001.

- Andrew Garnett: Friendship in Plato's Lysis, CUA Press 2012.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lysides. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Approaching Plato: A Guide to the Early and Middle Dialogues

Lysis public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Lysis public domain audiobook at LibriVox