Portal:Ancient Greek philosophy

Portal maintenance status: (November 2018)

|

Introduction

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC and continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Ancient Greece was part of the Roman Empire. Philosophy was used to make sense out of the world in a non-religious way. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics.

Greek philosophy has influenced much of Western culture since its inception. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato". Clear, unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers to Early Islamic philosophy, the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment.

Selected general articles

- Diairesis (Ancient Greek: διαίρεσις, translit. diaíresis, "division") is a form of classification used in ancient (especially Platonic) logic that serves to systematize concepts and come to definitions. When defining a concept using diairesis, one starts with a broad concept, then divides this into two or more specific sub-concepts, and this procedure is repeated until a definition of the desired concept is reached. Apart from this definition, the procedure also results in a taxonomy of other concepts, ordered according to a general–specific relation.

The founder of diairesis as a method was Plato. Later ancient logicians (including Aristotle) and practitioners of other ancient sciences have employed diairetic modes of classification, e.g., to classify plants in ancient biology. Although classification is still an important part of science, diairesis has been abandoned and is now of historical interest only. Read more... - Doxa (ancient Greek δόξα; from verb δοκεῖν dokein, "to appear", "to seem", "to think" and "to accept") is a Greek word meaning common belief or popular opinion. Used by the Greek rhetoricians as a tool for the formation of argument by using common opinions, the doxa was often manipulated by sophists to persuade the people, leading to Plato's condemnation of Athenian democracy.

The word doxa picked up a new meaning between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC when the Septuagint translated the Hebrew word for "glory" (כבוד, kavod) as doxa. This translation of the Hebrew Scriptures was used by the early church and is quoted frequently by the New Testament authors. The effects of this new meaning of doxa as "glory" is made evident by the ubiquitous use of the word throughout the New Testament and in the worship services of the Greek Orthodox Church, where the glorification of God in true worship is also seen as true belief. In that context, doxa reflects behavior or practice in worship, and the belief of the whole church rather than personal opinion. It is the unification of these multiple meanings of doxa that is reflected in the modern terms of orthodoxy and heterodoxy. This semantic merging in the word doxa is also seen in Russian word слава (slava), which means glory, but is used with the meaning of belief, opinion in words like православие (pravoslavie, meaning orthodoxy, or, literally, true belief). Read more... - In philosophy, anamnesis (/ˌænæmˈniːsɪs/; Ancient Greek: ἀνάμνησις) is a concept in Plato's epistemological and psychological theory that he develops in his dialogues Meno and Phaedo, and alludes to in his Phaedrus.

It is the idea that humans possess innate knowledge (perhaps acquired before birth) and that learning consists of rediscovering that knowledge within us. Read more... - In philosophy, becoming is the possibility of change in a thing that has being, that exists.

In the philosophical study of ontology, the concept of becoming originated in ancient Greece with the philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, who in the sixth century BC, said that nothing in this world is constant except change and becoming. This point was made by Heraclitus with the famous quote "No man ever steps in the same river twice." His theory stands in direct contrast to the philosophic idea of being, first argued by Parmenides, a Greek philosopher from the italic Magna Grecia, who believed that the change or "becoming" we perceive with our senses is deceptive, and that there is a pure perfect and eternal being behind nature, which is the ultimate truth of being. This point was made by Parmenides with the famous quote "what is-is". Becoming, along with its antithesis of being, are two of the foundation concepts in ontology. Scholars have generally believed that either Parmenides was responding to Heraclitus, or Heraclitus to Parmenides, though opinion on who was responding to who changed over the course of the 20th century. Read more... - In philosophy, Aporia (Ancient Greek: ᾰ̓πορῐ́ᾱ, translit. aporíā, lit. 'impasse, difficulty in passage, lack of resources, puzzlement') is a puzzle or state of puzzlement. In rhetoric, it is a useful expression of doubt. Read more...

- Ousia (/ˈuːziə,

ˈuːsiə, ˈuːʒə, ˈuːʃə/; Greek: οὐσία) is a philosophical and theological term, originally used in Ancient Greek philosophy, and also in Christian theology. It was used by various Ancient Greek philosophers, like Plato and Aristotle, as a primary designation for philosophical concepts of essence or substance. In contemporary philosophy, it is analogous to English concepts of being and ontic. In Christian theology, the concept of θεία ουσία (divine essence) is one of the most important doctrinal concepts, central to the development of trinitarian doctrine.

The Ancient Greek term Ousia was translated in Latin as essentia or substantia, and hence in English as essence or substance. Read more... - Arche (/ˈɑːrki/; Ancient Greek: ἀρχή) is a Greek word with primary senses "beginning", "origin" or "source of action" (εξ’ ἀρχής: from the beginning, οr εξ’ ἀρχής λόγος: the original argument), and later "first principle" or "element", first so used by Anaximander (Simplicius in Ph. 150.23). By extension, it may mean "first place, power", "method of government", "empire, realm", "authorities" (in plural: ἀρχαί), "command". The first principle or element corresponds to the "ultimate underlying substance" and "ultimate undemonstrable principle". In the philosophical language of the archaic period (8th to 6th century BC), arche (or archai) designates the source, origin or root of things that exist. In ancient Greek philosophy, Aristotle foregrounded the meaning of arche as the element or principle of a thing, which although undemonstrable and intangible in itself, provides the conditions of the possibility of that thing. Read more...

- Adiaphoron (/ædɪˈæfərɒn/, /ædiˈæfərɒn/ plural: adiaphora from the Greek ἀδιάφορα, the negation of διάφορα - Latin differentia - meaning "not differentiable").

In Cynicism "adiaphora" represents indifference to the vicissitudes of life. Read more...

The tetractys (Greek: τετρακτύς), or tetrad, or the tetractys of the decad is a triangular figure consisting of ten points arranged in four rows: one, two, three, and four points in each row, which is the geometrical representation of the fourth triangular number. As a mystical symbol, it was very important to the secret worship of Pythagoreanism. There were four seasons, and the number was also associated with planetary motions and music. Read more...- Phronesis (Ancient Greek: φρόνησῐς, translit. phrónēsis) is an Ancient Greek word for a type of wisdom or intelligence. It is more specifically a type of wisdom relevant to practical action, implying both good judgement and excellence of character and habits, or practical virtue. Phronesis was a common topic of discussion in ancient Greek philosophy.

The word was used in Greek philosophy, and such discussions are still influential today. In Aristotelian ethics, for example in the Nicomachean Ethics, it is distinguished from other words for wisdom and intellectual virtues – such as episteme and techne. Because of its practical character, when it is not simply translated by words meaning wisdom or intelligence, it is often translated as "practical wisdom", and sometimes (more traditionally) as "prudence", from Latin prudentia. Thomas McEvilley has proposed that the best translation is "mindfulness". Read more...  A sculpture representing Ethos outside the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly in Canberra, Australia

A sculpture representing Ethos outside the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly in Canberra, Australia

Ethos (/ˈiːθɒs/ or US: /ˈiːθoʊs/) is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the power of music to influence emotions, behaviours, and even morals. Early Greek stories of Orpheus exhibit this idea in a compelling way. The word's use in rhetoric is closely based on the Greek terminology used by Aristotle in his concept of the three artistic proofs or modes of persuasion. Read more... Personification of Wisdom (Koine Greek: Σοφία, Sophía) at the Library of Celsus in Ephesus (second century).

Personification of Wisdom (Koine Greek: Σοφία, Sophía) at the Library of Celsus in Ephesus (second century).

Sophia (Koine Greek: σοφία sophía "wisdom") is a central idea in Hellenistic philosophy and religion, Platonism, Gnosticism, and Christian theology. Originally carrying a meaning of "cleverness, skill", the later meaning of the term, close to the meaning of Phronesis ("wisdom, intelligence"), was significantly shaped by the term philosophy ("love of sophia") as used by Plato.

In the Eastern Orthodox and the Catholic churches, Holy Wisdom (Αγία Σοφία Hagía Sophía) is an expression for God the Son (Jesus) in the Trinity (as in the dedication of the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople) and, rarely, for the Holy Spirit. Read more... Greek spelling of logos

Greek spelling of logos

Logos (UK: /ˈloʊɡɒs,ˈlɒɡɒs/, US: /ˈloʊɡoʊs/; Ancient Greek: λόγος, translit. lógos; from λέγω, légō, lit. 'I say') is a term in Western philosophy, psychology, rhetoric, and religion derived from a Greek word variously meaning "ground", "plea", "opinion", "expectation", "word", "speech", "account", "reason", "proportion", and "discourse", but it became a technical term in Western philosophy beginning with Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC), who used the term for a principle of order and knowledge. Logos is the logic behind an argument. Logos tries to persuade an audience using logical arguments and supportive evidence. Logos is a persuasive technique often used in writing and rhetoric.

Ancient Greek philosophers used the term in different ways. The sophists used the term to mean discourse; Aristotle applied the term to refer to "reasoned discourse" or "the argument" in the field of rhetoric, and considered it one of the three modes of persuasion alongside ethos and pathos. Stoic philosophers identified the term with the divine animating principle pervading the Universe. Within Hellenistic Judaism, Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD) adopted the term into Jewish philosophy. The Gospel of John identifies the Logos, through which all things are made, as divine (theos), and further identifies Jesus Christ as the incarnate Logos. The term is also used in Sufism, and the analytical psychology of Carl Jung. Read more...

"Episteme" is a philosophical term derived from the Ancient Greek word ἐπιστήμη epistēmē, which can refer to knowledge, science or understanding, and which comes from the verb ἐπίστασθαι, meaning "to know, to understand, or to be acquainted with".

Plato contrasts episteme with "doxa": common belief or opinion. Episteme is also distinguished from "techne": a craft or applied practice. The word "epistemology" is derived from episteme. Read more...- Hypokeimenon (Greek: ὑποκείμενον), later often material substratum, is a term in metaphysics which literally means the "underlying thing" (Latin: subiectum).

To search for the hypokeimenon is to search for that substance which persists in a thing going through change—its basic essence. Read more... - Henosis (Ancient Greek: ἕνωσις) is the classical Greek word for mystical "oneness", "union" or "unity." In Platonism, and especially Neoplatonism, the goal of henosis is union with what is fundamental in reality: the One (Τὸ Ἕν), the Source, or Monad. The Neoplatonic concept has precedents in the Greek mystery religions as well as parallels in Eastern philosophy. It is further developed in the Corpus Hermeticum, in Christian theology, Alevism, soteriology and mysticism, and is an important factor in the historical development of monotheism during Late Antiquity. Read more...

.jpg/250px-Metempsychosis_by_Yokoyama_Taikan_(National_Museum_of_Modern_Art%2C_Tokyo).jpg) A section of Metempsychosis (1923) by Yokoyama Taikan; a drop of water from the vapours in the sky transforms into a mountain stream, which flows into a great river and on into the sea, whence rises a dragon (pictured) that turns back to vapour; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Important Cultural Property)

A section of Metempsychosis (1923) by Yokoyama Taikan; a drop of water from the vapours in the sky transforms into a mountain stream, which flows into a great river and on into the sea, whence rises a dragon (pictured) that turns back to vapour; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Important Cultural Property)

Metempsychosis (Greek: μετεμψύχωσις) is a philosophical term in the Greek language referring to transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. Generally, the term is derived from the context of ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualised by modern philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Kurt Gödel; otherwise, the term "transmigration" is more appropriate. The word plays a prominent role in James Joyce's Ulysses and is also associated with Nietzsche. Another term sometimes used synonymously is palingenesis. Read more...- In Stoic ethics, oikeiôsis (Ancient Greek: οἰκείωσις, Latin: conciliatio) is a technical term variously translated as "appropriation," "orientation," "familiarization," "affinity," "affiliation," and "endearment." Oikeiôsis signifies the perception of something as one’s own, as belonging to oneself. The theory of oikeiôsis can be traced back to the work of the first Stoic philosopher, Zeno of Citium.

The Stoic philosopher Hierocles saw it as the basis for all animal impulses as well as human ethical action. According to Porphyry, "those who followed Zeno stated that oikeiôsis is the beginning of justice". Read more... - Ataraxia (ἀταραξία, literally, "unperturbedness", generally translated as "imperturbability", "equanimity", or "tranquillity") is a Greek term first used in Ancient Greek philosophy by Pyrrho and subsequently Epicurus and the Stoics for a lucid state of robust equanimity characterized by ongoing freedom from distress and worry. In non-philosophical usage, the term was used to describe the ideal mental state for soldiers entering battle.

Achieving ataraxia is a common goal for Pyrrhonism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism, but the role and value of ataraxia within each philosophy varies depending their philosophical theories. The mental disturbances that prevent one from achieving ataraxia vary among the philosophies, and each philosophy has a different understanding as to how to achieve ataraxia. Read more...  The circled dot was used by the Pythagoreans and later Greeks to represent the first metaphysical being, the Monad or The Absolute.

The circled dot was used by the Pythagoreans and later Greeks to represent the first metaphysical being, the Monad or The Absolute.

Monad (from Greek μονάς monas, "singularity" in turn from μόνος monos, "alone") refers, in cosmogony, to the Supreme Being, divinity or the totality of all things. The concept was reportedly conceived by the Pythagoreans and may refer variously to a single source acting alone, or to an indivisible origin, or to both. The concept was later adopted by other philosophers, such as Leibniz, who referred to the monad as an elementary particle. It had a geometric counterpart, which was debated and discussed contemporaneously by the same groups of people. Read more...- The theory of Forms or theory of Ideas is a philosophical theory, concept, or world-view, attributed to Plato, that the physical world is not as real or true as timeless, absolute, unchangeable ideas. According to this theory, ideas in this sense, often capitalized and translated as "Ideas" or "Forms", are the non-physical essences of all things, of which objects and matter in the physical world are merely imitations. Plato speaks of these entities only through the characters (primarily Socrates) of his dialogues who sometimes suggest that these Forms are the only objects of study that can provide knowledge. The theory itself is contested from within Plato's dialogues, and it is a general point of controversy in philosophy. Whether the theory represents Plato's own views is held in doubt by modern scholarship. However, the theory is considered a classical solution to the problem of universals.

The early Greek concept of form precedes attested philosophical usage and is represented by a number of words mainly having to do with vision, sight, and appearance. Plato uses these aspects of sight and appearance from the early Greek concept of the form in his dialogues to explain the Forms and the Good. Read more... - In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in his Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics and De Anima, which is about the human psyche.

The concept of potentiality, in this context, generally refers to any "possibility" that a thing can be said to have. Aristotle did not consider all possibilities the same, and emphasized the importance of those that become real of their own accord when conditions are right and nothing stops them.

Actuality, in contrast to potentiality, is the motion, change or activity that represents an exercise or fulfillment of a possibility, when a possibility becomes real in the fullest sense. Read more... - Epoché (ἐποχή epokhē, "suspension") is an ancient Greek term typically translated as "suspension of judgment" but also as "withholding of assent". The term is used in slightly different ways among the various schools of Hellenistic philosophy.

The Pyrrhonists developed the concept of "epoché" to describe the state where all judgments about non-evident matters are suspended in order to induce a state of ataraxia (freedom from worry and anxiety). The Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus gives this definition: "Epoché is a state of the intellect on account of which we neither deny nor affirm anything." This concept is similarly employed in Academic Skepticism, but without the objective of ataraxia. Read more... - In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge (/ˈdɛmiˌɜːrdʒ/) is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term "demiurge". Although a fashioner, the demiurge is not necessarily the same as the creator figure in the monotheistic sense, because the demiurge itself and the material from which the demiurge fashions the universe are both considered to be consequences of something else. Depending on the system, they may be considered to be either uncreated and eternal or the product of some other entity.

The word "demiurge" is an English word derived from demiurgus, a Latinized form of the Greek δημιουργός or dēmiourgos. It was originally a common noun meaning "craftsman" or "artisan", but gradually came to mean "producer", and eventually "creator". The philosophical usage and the proper noun derive from Plato's Timaeus, written c. 360 BC, where the demiurge is presented as the creator of the universe. The demiurge is also described as a creator in the Platonic (c. 310–90 BC) and Middle Platonic (c. 90 BC – AD 300) philosophical traditions. In the various branches of the Neoplatonic school (third century onwards), the demiurge is the fashioner of the real, perceptible world after the model of the Ideas, but (in most Neoplatonic systems) is still not itself "the One". In the arch-dualist ideology of the various Gnostic systems, the material universe is evil, while the non-material world is good. According to some strains of Gnosticism, the demiurge is malevolent, as it is linked to the material world. In others, including the teaching of Valentinus, the demiurge is simply ignorant or misguided. Read more...  This diagram shows the medieval understanding of spheres of the cosmos, derived from Aristotle, and as per the standard explanation by Ptolemy. It came to be understood that at least the outermost sphere (marked "Primũ Mobile") has its own intellect, intelligence or nous - a cosmic equivalent to the human mind.

This diagram shows the medieval understanding of spheres of the cosmos, derived from Aristotle, and as per the standard explanation by Ptolemy. It came to be understood that at least the outermost sphere (marked "Primũ Mobile") has its own intellect, intelligence or nous - a cosmic equivalent to the human mind.

Nous (UK: /naʊs/, US: /nuːs/), sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, is a term from classical philosophy for the faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is true or real. English words such as "understanding" are sometimes used, but three commonly used philosophical terms come directly from classical languages: νοῦς or νόος (from Ancient Greek), intellēctus and intellegentia (from Latin). To describe the activity of this faculty, the word "intellection" is sometimes used in philosophical contexts, as well as the Greek words noēsis and noeîn (νόησις, νοεῖν). This activity is understood in a similar way (at least in some contexts) to the modern concept of intuition.

In philosophy, common English translations include "understanding" and "mind"; or sometimes "thought" or "reason" (in the sense of that which reasons, not the activity of reasoning). It is also often described as something equivalent to perception except that it works within the mind ("the mind's eye"). It has been suggested that the basic meaning is something like "awareness". In colloquial British English, nous also denotes "good sense", which is close to one everyday meaning it had in Ancient Greece. Read more...- A genus–differentia definition is a type of intensional definition, and it is composed of two parts:

- a genus (or family): An existing definition that serves as a portion of the new definition; all definitions with the same genus are considered members of that genus.

- the differentia: The portion of the definition that is not provided by the genus.

For example, consider these two definitions:- a triangle: A plane figure that has 3 straight bounding sides.

- a quadrilateral: A plane figure that has 4 straight bounding sides.

Those definitions can be expressed as one genus and two differentiae:- one genus:

- * the genus for both a triangle and a quadrilateral: "A plane figure"

- two differentiae:

- * the differentia for a triangle: "that has 3 straight bounding sides."

- * the differentia for a quadrilateral: "that has 4 straight bounding sides."

- Eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία [eu̯dai̯moníaː]), sometimes anglicized as eudaemonia or eudemonia /juːdɪˈmoʊniə/, is a Greek word commonly translated as happiness or welfare; however, "human flourishing or prosperity" has been proposed as a more accurate translation.[better source needed] Etymologically, it consists of the words "eu" ("good") and "daimōn" ("spirit"). It is a central concept in Aristotelian ethics and political philosophy, along with the terms "aretē", most often translated as "virtue" or "excellence", and "phronesis", often translated as "practical or ethical wisdom". In Aristotle's works, eudaimonia (based on older Greek tradition) was used as the term for the highest human good, and so it is the aim of practical philosophy, including ethics and political philosophy, to consider (and also experience) what it really is, and how it can be achieved.

Discussion of the links between virtue of character (ēthikē aretē) and happiness (eudaimonia) is one of the central concerns of ancient ethics, and a subject of much disagreement. As a result there are many varieties of eudaimonism. Two of the most influential forms are those of Aristotle and the Stoics. Aristotle takes virtue and its exercise to be the most important constituent in eudaimonia but acknowledges also the importance of external goods such as health, wealth, and beauty. By contrast, the Stoics make virtue necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia and thus deny the necessity of external goods. Read more... - Katalepsis (Greek: κατάληψις, "grasping") in Stoic philosophy, meant comprehension. To the Stoic philosophers, katalepsis was an important premise regarding one's state of mind as it relates to grasping fundamental philosophical concepts, and it represents the Stoic solution to the problem of the criterion. Read more...

- Apatheia (Greek: ἀπάθεια; from a- "without" and pathos "suffering" or "passion"), in Stoicism, refers to a state of mind in which one is not disturbed by the passions. It is best translated by the word equanimity rather than indifference. The meaning of the word apatheia is quite different from that of the modern English apathy, which has a distinctly negative connotation. According to the Stoics, apatheia was the quality that characterized the sage.

Whereas Aristotle had claimed that virtue was to be found in the golden mean between excess and deficiency of emotion (metriopatheia), the Stoics sought freedom from all passions (apatheia). It meant eradicating the tendency to react emotionally or egotistically to external events, the things that cannot be controlled. For Stoics, it was the optimum rational response to the world, for things cannot be controlled if they are caused by the will of others or by Nature; only one's own will can be controlled. That did not mean a loss of feeling, or total disengagement from the world. The Stoic who performs correct (virtuous) judgments and actions as part of the world order experiences contentment (eudaimonia) and good feelings (eupatheia). Read more... - Hylozoism is the philosophical point of view that matter is in some sense alive. The concept dates back at least as far as the Milesian school of pre-Socratic philosophers. The term was introduced to English by Ralph Cudworth in 1678. Read more...

- Kathēkon (Greek: καθῆκον) (plural: kathēkonta Greek: καθήκοντα) is a Greek concept, forged by the founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium. It may be translated as "appropriate behaviour", "befitting actions", or "convenient action for nature", or also "proper function". Kathekon was translated in Latin by Cicero as officium, and by Seneca as convenentia. Kathēkonta are contrasted, in Stoic ethics, with katorthōma (κατόρθωμα; plural: katorthōmata), roughly "perfect action". According to Stoic philosophy, humans (and all living beings) must act in accordance with Nature, which is the primary sense of kathēkon. Read more...

- Pathos (/ˈpeɪθɒs/, US: /ˈpeɪθoʊs/; plural: pathea; Greek: πάθος, for "suffering" or "experience"; adjectival form: pathetic from παθητικός) appeals to the emotions of the audience and elicits feelings that already reside in them. Pathos is a communication technique used most often in rhetoric (in which it is considered one of the three modes of persuasion, alongside ethos and logos), as well as in literature, film, and other narrative art.

Emotional appeal can be accomplished in many ways, such as the following:- by a metaphor or storytelling, commonly known as a hook;

- by passion in the delivery of the speech or writing, as determined by the audience; and

- by personal anecdote.

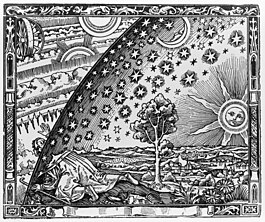

Flammarion engraving, Paris 1888

Flammarion engraving, Paris 1888

The cosmos (UK: /ˈkɒzmɒs/, US: /-moʊs/) is the universe. Using the word cosmos rather than the word universe implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity; the opposite of chaos.

The cosmos, and our understanding of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in cosmology – a very broad discipline covering any scientific, religious, or philosophical contemplation of the cosmos and its nature, or reasons for existing. Religious and philosophical approaches may include in their concepts of the cosmos various spiritual entities or other matters deemed to exist outside our physical universe. Read more...- Mimesis (/mɪˈmiːsɪs,

mə-, maɪ-, -əs/; Ancient Greek: μίμησις mīmēsis, from μιμεῖσθαι mīmeisthai, "to imitate", from μῖμος mimos, "imitator, actor") is a critical and philosophical term that carries a wide range of meanings, which include imitation, representation, mimicry, imitatio, receptivity, nonsensuous similarity, the act of resembling, the act of expression, and the presentation of the self.

In ancient Greece, mimesis was an idea that governed the creation of works of art, in particular, with correspondence to the physical world understood as a model for beauty, truth, and the good. Plato contrasted mimesis, or imitation, with diegesis, or narrative. After Plato, the meaning of mimesis eventually shifted toward a specifically literary function in ancient Greek society, and its use has changed and been reinterpreted many times since. Read more...

Arete (Greek: ἀρετή), in its basic sense, means "excellence of any kind". The term may also mean "moral virtue". In its earliest appearance in Greek, this notion of excellence was ultimately bound up with the notion of the fulfillment of purpose or function: the act of living up to one's full potential.

The term from Homeric times onwards is not gender specific. Homer applies the term of both the Greek and Trojan heroes as well as major female figures, such as Penelope, the wife of the Greek hero Odysseus. In the Homeric poems, Arete is frequently associated with bravery, but more often with effectiveness. The person of Arete is of the highest effectiveness; they use all their faculties—strength, bravery, and wit—to achieve real results. In the Homeric world, then, Arete involves all of the abilities and potentialities available to humans. Read more...- Hylomorphism (or hylemorphism) is a philosophical theory developed by Aristotle, which conceives being (ousia) as a compound of matter and form. The word is a 19th-century term formed from the Greek words ὕλη hyle, "wood, matter", and μορφή, morphē, "form". Read more...

- Physis (Greek: φύσις phusis) is a Greek theological, philosophical, and scientific term usually translated into English as "nature".

The term is central to Greek philosophy, and as a consequence to Western philosophy as a whole.

In pre-Socratic usage, phusis was contrasted with νόμος, nomoscode: lat promoted to code: la , "law, human convention."

Since Aristotle, however, the physical (the subject matter of physics, properly τὰ φυσικά "natural things") has more typically been juxtaposed to the metaphysical. Read more... - Hypostasis (Greek: ὑπόστασις) is the underlying state or underlying substance and is the fundamental reality that supports all else. In Neoplatonism the hypostasis of the soul, the intellect (nous) and "the one" was addressed by Plotinus.

In Christian theology, a hypostasis is one of the three hypostases (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) of the Trinity. Read more... - "Aponia" (Ancient Greek: ἀπονία) means the absence of pain, and was regarded by the Epicureans to be the height of bodily pleasure.

As with the other Hellenistic schools of philosophy, the Epicureans believed that the goal of human life is happiness. The Epicureans defined pleasure as the absence of pain (mental and physical), and hence pleasure can only increase until the point in which pain is absent. Beyond this, pleasure cannot increase further, and indeed one cannot rationally seek bodily pleasure beyond the state of aponia. For Epicurus, aponia was one of the static (katastematic) pleasures, that is, a pleasure one has when there is no want or pain to be removed. To achieve such a state, one has to experience kinetic pleasures, that is, a pleasure one has when want or pain is being removed. Read more... - Apeiron (/əˈpaɪrɒn/; ἄπειρον) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ἀ- a-, "without" and πεῖραρ peirar, "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of πέρας peras, "end, limit, boundary". It is akin to Persian piramon, meaning "boundary, circumference, surrounding". Read more...

- Hexis (Ancient Greek: ἕξις) is a relatively stable arrangement or disposition, for example a person's health or knowledge or character. It is an Ancient Greek word, important in the philosophy of Aristotle, and because of this it has become a traditional word of philosophy. It stems from a verb related to possession or "having", and Jacob Klein, for example, translates it as "possession". It is more typically translated in modern texts occasionally as "state" (e.g., H. Rackham), but more often as "disposition". Joe Sachs translates it as "active condition", in order to make sure that hexis is not confused with passive conditions of the soul, such as feelings and impulses or mere capacities that belong to us by nature. Sachs points to Aristotle's own distinction, explained for example in Categories 8b, which distinguishes the word diathesis, normally uncontroversially translated as disposition. In this passage, diathesis only applies to passive and shallow dispositions that are easy to remove and change, such as being hot or cold, while hexis is reserved for deeper and more active dispositions, such as properly getting to know something in a way that it will not be easily forgotten. Another common example of a human hexis in Aristotle is health (hugieia, or sometimes eu(h)exia, in Greek) and in cases where hexis is discussed in the context of health, it is sometimes translated as "constitution".

Apart from needing to be relatively stable or permanent, in contexts concerning humans (such as knowledge, health, and good character) hexis is also generally understood to be contrasted from other dispositions, conditions and habits, by being "acquired" by some sort of training or other habituation. Read more... - In philosophy, being means the existence of a thing. Anything that exists has being. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that studies being. Being is a concept encompassing objective and subjective features of reality and existence. Anything that partakes in being is also called a "being", though often this usage is limited to entities that have subjectivity (as in the expression "human being"). The notion of "being" has, inevitably, been elusive and controversial in the history of philosophy, beginning in Western philosophy with attempts among the pre-Socratics to deploy it intelligibly. The first effort to recognize and define the concept came from Parmenides, who famously said of it that "what is-is". Common words such as "is", "are", and "am" refer directly or indirectly to being.

As an example of efforts in recent times, Martin Heidegger (who himself drew on ancient Greek sources) adopted after German terms like Dasein to articulate the topic. Several modern approaches build on such continental European exemplars as Heidegger, and apply metaphysical results to the understanding of human psychology and the human condition generally (notably in the Existentialist tradition). By contrast, in mainstream Analytical philosophy the topic is more confined to abstract investigation, in the work of such influential theorists as W. V. O. Quine, to name one of many. One of the most fundamental questions that has been contemplated in various cultures and traditions (e.g., Native American) and continues to exercise philosophers is articulated thusly by William James: "How comes the world to be here at all instead of the nonentity which might be imagined in its place? ... from nothing to being there is no logical bridge." Read more...

Need help?

Do you have a question about Ancient Greek philosophy that you can't find the answer to?

Consider asking it at the Wikipedia reference desk.

Selected images

The School of Athens (1509–1511) by Raphael, depicting famous classical Greek philosophers in an idealized setting inspired by ancient Greek architecture

- The philosopher Pyrrho of Elis, in an anecdote taken from Sextus Empiricus' Outlines of Pyrrhonism

(upper)PIRRHO • HELIENSIS •

PLISTARCHI • FILIVS

translation (from Latin): Pyrrho • Greek • Son of Plistarchus(middle)OPORTERE • SAPIENTEM

HANC ILLIVS IMITARI

SECVRITATEMtranslation (from Latin): It is right wisdom then that all imitate this security (Pyrrho pointing at a peaceful pig munching his food)(lower)Whoever wants to apply the real wisdom, shall not mind trepidation and misery

Subcategories

- Select [►] to view subcategories

Subtopics

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Wikibooks

Books

Commons

Media

Wikinews

News

Wikiquote

Quotations

Wikisource

Texts

Wikiversity

Learning resources

Wiktionary

Definitions

Wikidata

Database

- What are portals?

- List of portals