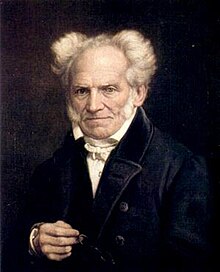

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1788 |

| Died | 21 September 1860 (aged 72) |

| Residence | Danzig, Hamburg, Frankfurt |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Berlin |

Main interests | Metaphysics, aesthetics, ethics, morality, psychology |

Notable ideas | Anthropic principle[6][7] Eternal justice Fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason Hedgehog's dilemma Philosophical pessimism Principium individuationis Will as thing in itself Schopenhauerian aesthetics |

Influenced

| |

| Signature | |

Arthur Schopenhauer (/ˈʃoʊpənhaʊ.ər/ SHOH-pən-how-ər;[15] German: [ˈʔaɐ̯tʊɐ̯ ˈʃoːpm̩ˌhaʊ̯ɐ]; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation (expanded in 1844), wherein he characterizes the phenomenal world as the product of a blind and insatiable metaphysical will.[16][17] Proceeding from the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant, Schopenhauer developed an atheistic metaphysical and ethical system that has been described as an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism,[18][19][20] rejecting the contemporaneous post-Kantian philosophies of German idealism.[21][22] Schopenhauer was among the first thinkers in Western philosophy to share and affirm significant tenets of Eastern philosophy (e.g., asceticism, the world-as-appearance), having initially arrived at similar conclusions as the result of his own philosophical work.[23][24]

Though his work failed to garner substantial attention during his life, Schopenhauer has had a posthumous impact across various disciplines, including philosophy, literature, and science. His writing on aesthetics, morality, and psychology influenced thinkers and artists throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Those who cited his influence include Friedrich Nietzsche,[25] Richard Wagner, Leo Tolstoy, Ludwig Wittgenstein,[26] Erwin Schrödinger, Otto Rank, Gustav Mahler, Joseph Campbell, Albert Einstein,[27] Carl Jung, Thomas Mann, Émile Zola, George Bernard Shaw,[28] Jorge Luis Borges and Samuel Beckett.[29]

Contents

- 1 Life

- 2 Philosophy

- 3 Interests

- 4 Thoughts on other philosophers

- 5 Influence

- 6 Selected bibliography

- 7 See also

- 8 References

- 9 Further reading

- 10 External links

Life[edit]

Early life[edit]

Schopenhauer was born on 22 February 1788, in the city of Danzig (then part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; present day Gdańsk, Poland) on Heiligegeistgasse (known in the present day as Św. Ducha 47), the son of Johanna Schopenhauer (née Trosiener) and Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer,[30] both descendants of wealthy German-Dutch patrician families. Neither of them was very religious,[31]; each supported the French Revolution,[32] and was republican, cosmopolitan and Anglophile.[33] When Danzig became part of Prussia in 1793, Heinrich moved to Hamburg - a free city with republican constitution, protected by Britain and Holland against Prussian aggression - although his firm continued trading in Danzig where most of their extended families remained. Adele, Arthur's only sibling was born on 12 July 1797.

In 1797 Arthur was sent to Le Havre to live for two years with the family of his father's business associate, Grégoire de Blésimaire. He seemed to enjoy his stay there, learned to speak French fluently and started a friendship with Jean Anthime Grégoire de Blésimaire, his peer, which lasted for a large part of their lives.[34] As early as 1799, Arthur started playing the flute.[35]:30 In 1803 he joined his parents on their long tour of Holland, Britain, France, Switzerland, Austria and Prussia; it was mostly a pleasure tour although Heinrich also visited some of his business associates. Heinrich gave his son a choice - he could stay at home and start preparations for university education, or he could travel with them and then continue his merchant education. Arthur later deeply regretted his choice because he found his merchant training tedious. He spent twelve weeks of the tour attending a school in Wimbledon where he was very unhappy and appalled by strict but intellectually shallow Anglican religiosity, which he continued to sharply criticize later in life despite his general Anglophilia.[36] He was also under great pressure from his father who became very critical of his educational results. In fact Heinrich Floris became so fussy that even his wife started to doubt his mental health.[37]

In 1805, Heinrich Floris died by drowning in a canal by their home in Hamburg. Although it was possible that his death was accidental, his wife and son believed that it was suicide because he was very prone to unsociable behavior, anxiety and depression which became especially pronounced in his last months of life.[38][39] Arthur showed similar moodiness since his youth and often acknowledged that he inherited it from his father; there were also several other instances of serious mental health issues on his father's side of family.[40] His mother Johanna was generally described as vivacious and sociable.[33] Despite the hardships, Schopenhauer seemed to like his father and later mentioned him always in a positive light.[37][41] Heinrich Schopenhauer left the family with a significant inheritance that was split in three among Johanna and the children. Arthur Schopenhauer was entitled to control of his part when he reached the age of majority. He invested it conservatively in government bonds and earned annual interest that was more than double the salary of a university professor.[42]

Arthur endured two long years of drudgery as a merchant in honor of his dead father, and because of his own doubts about being too old to start a life of a scholar.[43] Most of his prior education was practical merchant training and he had some trouble with learning Latin which was a prerequisite for any academic career.[44] His mother soon moved with his sister Adele to Weimar—then the centre of German literature—to enjoy social life among celebrated writers and artists. Arthur lived in Hamburg with his friend Jean Anthime who was also studying to become a merchant.

After quitting his merchant apprenticeship, with some encouragement from his mother, he dedicated himself to studies at the Gotha gymnasium (Gymnasium illustre zu Gotha) in Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, but he also enjoyed social life among local nobility spending large amounts of money which caused concern to his frugal mother.[45] He left Gymnasium after writing a satirical poem about one of the lecturers. Although Arthur claimed that he left voluntarily, his mother's letter indicates that he was expelled.[46]

Education[edit]

He moved to Weimar but didn't live with his mother who even tried to discourage him from coming by explaining that they wouldn't get along very well.[47] Their relationship deteriorated even further due to their temperamental differences. He accused his mother of being financially irresponsible, flirtatious and seeking to remarry, which he considered an insult to his father's memory.[48][47] His mother, while professing her love to him, criticized him sharply for being moody, tactless, and argumentative—and urged him to improve his behavior so he would not alienate people.[46] Arthur concentrated on his studies which were now going very well and he also enjoyed the usual social life such as balls, parties and theater. By that time Johanna's famous salon was well established among local intellectuals and dignitaries, most celebrated of them being Goethe. Arthur attended her parties, usually when he knew that Goethe would be there—though the famous writer and statesman didn't even seem to notice the young and unknown student. It is possible that Goethe kept distance because Johanna warned him about her son's depressive and combative nature, or because Goethe was then on bad terms with Arthur's language instructor and roommate, Franz Passow.[49] Schopenhauer was also captivated by the beautiful Karoline Jagemann, mistress of Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, and he wrote to her his only known love poem.[50] Despite his later celebration of asceticism and negative views of sexuality, Schopenhauer occasionally had sexual affairs, usually with women of lower social status, such as servants, actresses, and sometimes even paid prostitutes.[51] In a letter to his friend Anthime he claims that such affairs continued even in his mature age and admits that he had two out-of-wedlock daughters (born in 1819 and 1836), both of whom died in infancy.[52] In their youthful correspondence Arthur and Anthime were somewhat boastful and competitive about their sexual exploits—but Schopenhauer seemed aware that women usually didn't find him very charming or physically attractive, and his desires often remained unfulfilled.[53]

He left Weimar to become a student at the University of Göttingen in 1809. There are no written reasons about why Schopenhauer chose that university instead of then more famous University of Jena but Göttingen was known as a more modern, scientifically oriented, with less attention given to theology.[54] Law or medicine were usual choices for young men of Schopenhauer's status who also needed career and income; he choose medicine due to his scientific interests. Among his notable professors were Bernhard Friedrich Thibaut, Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, Friedrich Stromeyer, Heinrich Adolf Schrader, Johann Tobias Mayer and Konrad Johann Martin Langenbeck.[55] He studied metaphysics, psychology and logic under Gottlob Ernst Schulze, the author of Aenesidemus, who made a strong impression and advised him to concentrate on Plato and Immanuel Kant.[56] He decided to switch from medicine to philosophy around 1810-11 and he left Göttingen which didn't have a strong philosophy program (besides Schulze the only other philosophy professor was Friedrich Bouterwek whom Schopenhauer disliked[57]). He didn't regret his medicinal and scientific studies. He claimed that they were necessary for a philosopher, and even in Berlin he attended more lectures in sciences than in philosophy.[58] During his days at Göttingen, he spent a lot of time studying, but also continued his flute playing and social life. His friends included Friedrich Gotthilf Osann, Karl Witte, Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen, and William Backhouse Astor Sr..[59]

He arrived to the newly founded University of Berlin for the winter semester of 1811-12. At the same time his mother just started her literary career; she published her first book in 1810, a biography of her friend Karl Ludwig Fernow, which was a critical success. Arthur attended lectures by the prominent post-Kantian philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte but quickly found many points of disagreement with his Wissenschaftslehre and he also found his lectures tedious and hard to understand.[60] He later mentioned Fichte only in critical, negative terms[60]—seeing his philosophy as a lower quality version of Kant's and considering it useful only because Fichte's poor arguments unintentionally highlighted some failings of Kantianism.[61] He also attended the lectures of the famous theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher whom he also quickly came to dislike.[62] His notes and comments on Schleiermacher's lectures show that Schopenhauer was becoming very critical of religion and moving towards atheism.[63] He learned a lot by self-directed reading; besides Plato, Kant and Fichte he also read the works of Schelling, Fries, Jacobi, Bacon, Locke, and a lot of current scientific literature.[58] He attended philological courses by August Böckh and Friedrich August Wolf and continued his naturalistic interests with courses by Martin Heinrich Klaproth, Paul Erman, Johann Elert Bode, Ernst Gottfried Fischer, Johann Horkel, Friedrich Christian Rosenthal and Hinrich Lichtenstein (Lichtenstein was also a friend whom he met at one of his mother's parties in Weimar).[64]

Early work[edit]

Schopenhauer left Berlin in a rush in 1813 fearing that the city could be attacked and that he could be pressed into military service as Prussia just joined the war against France.[65] He returned to Weimar but left after less than a month disgusted by the fact that his mother was now living with her supposed lover, Georg Friedrich Conrad Ludwig Müller von Gerstenbergk, a civil servant fourteen years younger than her; he considered the relationship an act of infidelity to his father's memory.[66] He settled for a while in Rudolstadt hoping that no army would pass through the small town. He spent his time in solitude, hiking in the mountains and the Thuringian forest and writing his dissertation, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason. He completed his dissertation at about the same time as the French army was defeated at the Battle of Leipzig. He became irritated by the arrival of soldiers to the town and accepted his mother's invitation to visit her in Weimar. She tried to convince him that her relationship with Gerstenbergk was platonic and that she had no intentions of remarrying.[67] But Schopenhauer remained suspicious and often came in conflict with Gerstenbergk because he considered him untalented, pretentious, and nationalistic.[68] His mother just published her second book, Reminiscences of a Journey in the Years 1803, 1804, and 1805, a description of their family tour of Europe, which quickly became a hit. She found his dissertation incomprehensible and said it was unlikely that anyone would ever buy a copy. In a fit of temper Arthur told her that people would read his work long after the "rubbish" she wrote was totally forgotten.[69][70] In fact, although they considered her novels of dubious quality, the Brockhaus publishing firm held her in high esteem because they consistently sold well. Hans Brockhaus (1888-1965) later claimed that his predecessors "...saw nothing in this manuscript, but wanted to please one of our best-selling authors by publishing her son's work. We published more and more of her son Arthur's work and today nobody remembers Johanna, but her son's works are in steady demand and contribute to Brockhaus'[s] reputation."[71] He kept large portraits of the pair in his office in Leipzig for the edification of his new editors.[71]

Also contrary to his mother's prediction, Schopenhauer's dissertation made an impression on Goethe to whom he sent it as a gift.[72] Although it is doubtful that Goethe agreed with Schopenhauer's philosophical positions he was impressed by his intellect and extensive scientific education.[73] Their subsequent meetings and correspondence were a great honor to a young philosopher who was finally acknowledged by his intellectual hero. They mostly discussed Goethe's newly published (and somewhat lukewarmly received) work on color theory. Schopenhauer soon started writing his own treatise on the subject, On Vision and Colors, which in many points differed from his teacher's. Although they remained polite towards each other, their growing theoretical disagreements – and especially Schopenhauer's tactless criticisms and extreme self-confidence – soon made Goethe become distant again and after 1816 their correspondence became less frequent.[74] Schopenhauer later admitted that he was greatly hurt by this rejection, but he continued to praise Goethe, and considered his color theory a great introduction to his own.[75][76][77]

Another important experience during his stay in Weimar was his acquaintance with Friedrich Majer – a historian of religion, orientalist and disciple of Herder – who introduced him to the Eastern philosophy.[78] Schopenhauer was immediately impressed by the Upanishads and the Buddha and put them at par with Plato and Kant.[79][80] He continued his studies by reading the Bhagavad Gita, an amateurish German journal Asiatisches Magazin and Asiatick Researches by The Asiatic Society.[81][80] Although he loved Hindu texts he was more interested in Buddhism, which he came to regard as the best religion.[80] However, his early studies were constrained by the lack of adequate literature, and were mostly restricted to Early Buddhism. He also claimed that he formulated most of his ideas independently, and only later realized the similarities with Buddhism.[82]

As the relationship with his mother fell to a new low he left Weimar and moved to Dresden in May 1814.[76] He continued his philosophical studies, enjoyed the cultural life, socialized with intellectuals and engaged in sexual affairs.[83] His friends in Dresden were Johann Gottlob von Quandt, Friedrich Laun, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause and Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl, a young painter who made a romanticized portrait of him in which he improved some of Schopenhauer's unattractive physical features.[84][85] His criticisms of local artists occasionally caused public quarrels when he ran into them in public.[86] However, his main occupation during his stay in Dresden was his seminal philosophical work, The World as Will and Representation, which he started writing in 1814 and finished in 1818.[87] He was recommended to Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus by Baron Ferdinand von Biedenfeld, an acquaintance of his mother.[88] Although the publisher accepted his manuscript, Schopenhauer made a poor impression because of his quarrelsome and fussy attitude and very poor sales of the book after it was published in December 1818.[89]

In September 1818, while waiting for his book to be published and conveniently escaping an affair with a maid that caused an unwanted pregnancy,[90] Schopenhauer left Dresden for a yearlong vacation in Italy.[91] He visited Venice, Bologna, Florence, Naples and Milan, travelling alone or accompanied by mostly English tourists he met.[92] He spent winter months in Rome where he accidentally met his acquaintance Karl Witte and engaged in numerous quarrels with German tourists in Caffe Greco, among them Johann Friedrich Böhmer who also mentioned his insulting remarks and unpleasant character.[93] He enjoyed art, architecture, ancient ruins, attended plays and operas, continued his philosophical contemplation and love affairs.[94] One of his affairs supposedly became serious, and for a while he contemplated marriage to a rich Italian noblewoman—but despite his mentioning this several times, no details are known and it may have been Schopenhauer exaggerating.[95][96] He corresponded regularly with his sister Adele and became close to her as her relationship with Johanna and Gerstenbergk also deteriorated.[97] She informed him about their financial troubles as the banking house of A. L. Muhl in Danzig – in which her mother invested their whole savings and Arthur a third of his – was near bankruptcy.[98] Arthur offered to share his assets but his mother refused and became further enraged by his insulting comments.[99] The women managed to receive only thirty percent of their savings while Arthur, using his business knowledge, took a suspicious and aggressive stance towards the banker and eventually received his part in full.[100] The affair additionally worsened the relationships among all three members of Schopenhauer family.[99][101]

He shortened his stay in Italy because of the trouble with Muhl and returned to Dresden.[102] Disturbed by the financial risk and the lack of responses to his book he decided to take an academic position since it provided him both with income and the opportunity to promote his views.[103] He contacted his friends at universities in Heidelberg, Göttingen and Berlin and found Berlin most attractive.[104] He scheduled his lectures to coincide with those of the famous philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whom Schopenhauer described as a "clumsy charlatan".[105] He was especially appalled by Hegel's supposedly poor knowledge of natural sciences and tried to engage him in a quarrel about it already at his test lecture in March 1820.[106] Hegel was also facing political suspicions at the time when many progressive professors were fired, while Schopenhauer carefully mentioned in his application that he had no interest in politics.[107] Despite their differences and the arrogant request to schedule lectures at the same time as his own, Hegel still voted to accept Schopenhauer to the university.[108] However, only five students turned up to Schopenhauer's lectures, and he dropped out of academia. A late essay, On University Philosophy, expressed his resentment towards the work conducted in academies.

Later life[edit]

After his academic failure he continued to travel extensively, visiting Leipzig, Nuremberg, Stuttgart, Schaffhausen, Vevey, Milan and spending eight months in Florence.[109] However, before he left for his three-year travel, he had an incident with his Berlin neighbor, forty-seven-year-old seamstress Caroline Louise Marquet. The details of the August 1821 incident are unknown. He claimed that he just pushed her from his entrance after she rudely refused to leave, and she purposely fell on the ground so she could sue him. She claimed that he attacked her so violently that she had become paralyzed on her right side and unable to work. She immediately sued him, and the process lasted until May 1827, when a court found Schopenhauer guilty and forced him to pay her an annual pension until her death in 1842.[110]

Schopenhauer enjoyed Italy, where he studied art and socialized with Italian and English nobles.[111] It was his last visit to the country. He left for Munich and stayed there for a year, mostly recuperating from various health issues, some of them possibly caused by venereal diseases (the treatment his doctor used suggests syphilis).[112] He contacted publishers offering to translate Hume into German and Kant into English but his proposals were declined.[113][114] Returning to Berlin he began to study Spanish so he could read some of his favorite authors in their original language. He liked Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Lope de Vega, Miguel de Cervantes, and especially Baltasar Gracián.[115] He also made failed attempts to publish his translations of their works. Few attempts to revive his lectures – again scheduled at the same time as Hegel's – also failed, as did his inquiries about relocating to other universities.[116]

During his Berlin years Schopenhauer occasionally mentioned his desire to marry and have a family.[117][118] For a while he was unsuccessfully courting 17-year-old Flora Weiss, who was 22 years younger than him.[119] His unpublished writings from that time show that he was already very critical of monogamy but still not advocating polygyny – instead musing about a polyamorous relationship he called tetragamy.[120] He had an on and off relationship with a young dancer Caroline Richter (she also used surname Medon after one of her ex-lovers).[121] They met when he was 33 and she was 19 and working at the Berlin Opera. She already had numerous lovers and an out-of-wedlock son, and later gave birth to another son, this time to an unnamed foreign diplomat. (She soon had another pregnancy but it was stillborn).[122] As Schopenhauer was preparing to escape Berlin in 1831, due to cholera epidemic, he offered to take her with him on the condition that she leaves her young son.[117] She refused and he went alone; in his will he left her a significant sum of money but insisted that it should not be in any way spent on her second son.[117]

Schopenhauer claimed that in his last year in Berlin, he had a prophetic dream that urged him to escape the city.[123] As he arrived in his new home in Frankfurt he supposedly had another supernatural experience, an apparition of his dead father and his mother who was still alive.[123] This experience led him to spend some time investigating paranormal phenomena and magic. He was quite critical of the available studies and claimed that they were mostly ignorant or fraudulent, but he did believe that there are authentic cases of such phenomena and tried to explain them through his metaphysics as manifestations of the will.[124]

Upon his arrival in Frankfurt he experienced a period of depression and declining health.[125] He renewed his correspondence with his mother, and she seemed concerned that he might commit suicide like his father.[126] By now Johanna and Adele were living very modestly. Johanna's writing didn't bring her much income, and her popularity was waning.[127] Their correspondence remained reserved, and Arthur Schopenhauer seemed undisturbed by her death in 1838.[128] His relationship with his sister grew closer and he corresponded with her until she died in 1849.[129]

In July 1832 Schopenhauer left Frankfurt for Mannheim but returned in July 1833 to remain there for the rest of his life, except for a few short journeys.[130] He lived alone except for a succession of pet poodles named Atman and Butz. In 1836, he published On the Will in Nature. In 1836 he sent his essay On the Freedom of the Will to the contest of the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and won the prize next year. He sent another essay, On the Basis of Morality, to the Royal Danish Society for Scientific Studies but didn't win the prize despite being the only contestant. The Society was appalled that several distinguished contemporary philosophers were mentioned in a very offensive manner, claimed that the essay missed the point and that the arguments were not adequate.[131] Schopenhauer, who was very self-confident that he will win, was enraged by this rejection. He published both essays as The Two Basic Problems of Ethics and in the preface to the second edition of this book, in 1860, he was still pouring insults on Royal Danish Society.[132] First edition, published in 1841, again failed to draw attention to his philosophy. Two years later, after some negotiations, he managed to convince his publisher, Brockhaus, to print the second, updated edition of The World as Will and Representation. The book was again mostly ignored and few reviews were mixed or negative.

However, Schopenhauer did start to attract some followers, mostly outside academia, among practical professionals (several of them were lawyers) who pursued private philosophical studies. He jokingly referred to them as evangelists and apostles.[133] One of the most active early followers was Julius Frauenstädt who wrote numerous articles promoting Schopenhauer's philosophy. He was also instrumental in finding another publisher after Brockhaus refused to publish Parerga and Paralipomena believing that it would be another failure.[134] Though Schopenhauer later stopped corresponding with him, claiming that he did not adhere closely enough to his ideas, Frauenstädt continued to promote Schopehnauer's work.[135] They renewed their communication in 1859 and Schopenhauer named him heir for his literary estate.[136] He also became the editor of the first collected works of Schopenhauer.[134]

In 1848 Schopenhauer witnessed violent upheaval in Frankfurt after General Hans Adolf Erdmann von Auerswald and Prince Felix Lichnowsky were murdered. He became worried for his own safety and property.[137] Even earlier in life he had such worries and kept a sword and loaded pistols near his bed to defend himself from thieves.[138] He gave a friendly welcome to Austrian soldiers who wanted to shoot revolutionaries from his window and as they were leaving he gave one of the officers his opera glasses to help him monitor rebels.[137] The rebellion passed without any loss to Schopenhauer and he later praised Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz for restoring order.[139] He even modified his will, leaving a large part of his property to a Prussian fund that helped soldiers who became invalids while fighting rebellion in 1848 or the families of soldiers who died in battle.[140] As Young Hegelians were advocating change and progress Schopenhauer claimed that misery is natural for humans—and that even if some utopian society were established, people would still fight each other out of boredom, or would starve due to overpopulation.[139]

In 1851 Schopenhauer published Parerga and Paralipomena, which, as the title says, contains essays that are supplementary to his main work, and are mostly comprehensible to readers unfamiliar with his earlier philosophy. It was his first successful, widely read book, partly due to the work of his disciples who wrote praising reviews.[141] The essays that proved most popular were the ones that actually didn't contain the basic philosophical ideas of his system.[142] Many academic philosophers considered him a great stylist and cultural critic but didn't take his philosophy seriously.[142] His early critics liked to point out similarities of his ideas to those Fichte and Schelling,[143] or claim that there are numerous contradictions in his philosophy.[143][144] Both criticisms enraged Schopenhauer. However, he was becoming less interested in intellectual fights, but encouraged his disciples to do so.[145] His private notes and correspondence show that he acknowledged some of the criticisms regarding contradictions, inconsistencies, and vagueness in his philosophy, but claimed that he wasn't concerned about harmony and agreement in his propositions[146] and that some of his ideas shouldn't be taken literally but instead as metaphors.[147]

Academic philosophers were also starting to notice his work. In 1856 University of Leipzig sponsored an essay contest about Schopenhauer's philosophy, which was won by Rudolf Seydel’s very critical essay.[148] Schopenhauer's friend Jules Lunteschütz made a first of his four portraits of him – which Schopenhauer didn't particularly like – that was soon sold to a wealthy landowner Carl Ferdinand Wiesike who built a house to display it. Schopenhauer seemed flattered and amused by this, and would claim that it was his first chapel.[149] As his fame increased copies of his paintings and photographs were being sold and admirers were visiting the places where he lived and wrote his works. People visited Frankfurt's Englischer Hof to observe him dining. Admirers gave him gifts and asked for autographs.[150] He complained, however, that he still felt isolated due to his not very social nature and the fact that many of his good friends already died from old age.[151]

He remained healthy in his old age, which he attributed to regular walks no matter the weather, and always getting enough sleep.[152] He had a great appetite and could read without glasses but his hearing was declining since his youth and he developed problems with rheumatism.[153] He remained active and lucid, continued his reading, writing and correspondences until his death.[153] The numerous notes that he made during these years, amongst others on aging, were published posthumously under the title Senilia. In the spring of 1860 his health started to decline, he experienced shortness of breath and heart palpitations; in September he suffered inflammation of the lungs and although he was starting to recover he remained very weak.[154] His last friend to visit him was Wilhelm Gwinner and according to him Schopenhauer was concerned that he won't be able to finish his planned additions to Parerga and Paralipomena but was at peace with dying.[155] He died of pulmonary-respiratory failure,[156] on 21 September 1860 while sitting at home on his couch. He was 72.[157]

Philosophy[edit]

The world as representation[edit]

Schopenhauer saw his philosophy as a continuation of that of Kant, and used the results of his epistemological investigations, that is, transcendental idealism, as starting point for his own:

My philosophy is founded on that of Kant, and therefore presupposes a thorough knowledge of it. Kant's teaching produces in the mind of everyone who has comprehended it a fundamental change which is so great that it may be regarded as an intellectual new-birth. It alone is able really to remove the inborn realism which proceeds from the original character of the intellect, which neither Berkeley nor Malebranche succeed in doing, for they remain too much in the universal, while Kant goes into the particular, and indeed in a way that is quite unexampled both before and after him, and which has quite a peculiar, and, we might say, immediate effect upon the mind in consequence of which it undergoes a complete undeception, and forthwith looks at all things in another light. Only in this way can anyone become susceptible to the more positive expositions which I have to give.[158]

Kant had argued the empirical world is merely a complex of appearances whose existence and connection occur only in our representations.[159] Schopenhauer reiterates this in the first sentence of his main work: "The world is my representation." We do not draw empirical laws from nature, but prescribe them to it.[160]

Schopenhauer praises Kant for his distinction between appearance and the things-in-themselves that appear, whereas the general consensus in German Idealism was that this was the weakest spot of Kant's theory,[161] since according to Kant causality can find application on objects of experience only, and consequently, things-in-themselves cannot be the cause of appearances, as Kant argued. The inadmissibility of this reasoning was also acknowledged by Schopenhauer. He insisted that this distinction was a true conclusion, drawn from false premises.[162]

Theory of perception[edit]

In November 1813 Goethe invited Schopenhauer for research on his Theory of Colours. Although Schopenhauer considered colour theory a minor matter,[163] he accepted the invitation out of admiration for Goethe. Nevertheless, these investigations led him to his most important discovery in epistemology: finding a demonstration for the a priori nature of causality.

Kant openly admitted that it was Hume's skeptical assault on causality that motivated the critical investigations of Critique of Pure Reason. In it, he gives an elaborate proof to show that causality is given a priori. After G.E. Schulze had made it plausible that Kant had not disproven Hume's skepticism, it was up to those loyal to the project of Kant to prove this important matter.

The difference between the approach of Kant and Schopenhauer was this: Kant simply declared that the empirical content of perception is "given" to us from outside, an expression with which Schopenhauer often expressed his dissatisfaction.[164] He, on the other hand, was occupied with: how do we get this empirical content of perception; how is it possible to comprehend subjective sensations limited to my skin as the objective perception of things that lie outside of me?[165]

The sensations in the hand of a man born blind, on feeling an object of cubic shape, are quite uniform and the same on all sides and in every direction: the edges, it is true, press upon a smaller portion of his hand, still nothing at all like a cube is contained in these sensations. His Understanding, however, draws the immediate and intuitive conclusion from the resistance felt, that this resistance must have a cause, which then presents itself through that conclusion as a hard body; and through the movements of his arms in feeling the object, while the hand's sensation remains unaltered, he constructs the cubic shape in Space. If the representation of a cause and of Space, together with their laws, had not already existed within him, the image of a cube could never have proceeded from those successive sensations in his hand.[166]

Causality is therefore not an empirical concept drawn from objective perceptions, but objective perception presupposes knowledge of causality. Hereby Hume's skepticism is disproven.[167]

By this intellectual operation, comprehending every effect in our sensory organs as having an external cause, the external world arises. With vision, finding the cause is essentially simplified due to light acting in straight lines. We are seldom conscious of the process, that interprets the double sensation in both eyes as coming from one object; that turns the upside down impression; and that adds depth to make from the planimetrical data stereometrical perception with distance between objects.

Schopenhauer stresses the importance of the intellectual nature of perception, the senses furnish the raw material by which the intellect produces the world as representation. He set out his theory of perception for the first time in On Vision and Colors,[161] and in the subsequent editions of Fourfold Root an extensive exposition is given in § 21.

The world as will[edit]

Schopenhauer developed a system called metaphysical voluntarism.

The kernel and chief point of my doctrine, its Metaphysic proper, is this, that what Kant opposed as thing-in-itself to mere appearance (called more decidedly by me "representation") and what he held to be absolutely unknowable, that this thing-in-itself, I say, this substratum of all appearances, and therefore of the whole of Nature, is nothing but what we know directly and intimately and find within ourselves as will; that accordingly, this will, far from being inseparable from, and even a mere result of, knowledge, differs radically and entirely from, and is quite independent of, knowledge, which is secondary and of later origin; and can consequently subsist and manifest itself without knowledge: that this will, being the one and only thing-in-itself, the sole truly real, primary, metaphysical thing in a world in which everything else is only appearance, i.e., mere representation, gives all things, whatever they may be, the power to exist and to act; ... is absolutely identical with the will we find within us and know as intimately as we can know any thing; that, on the other hand, knowledge with its substratum, the intellect, is a merely secondary phenomenon, differing completely from the will, only accompanying its higher degrees of objectification and not essential to it; ... that we are never able therefore to infer absence of will from absence of knowledge.

— On the Will in Nature, Introduction

For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world. Einstein paraphrased his views as follows: "Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wants."[citation needed] In this sense, he adhered to the Fichtean principle of idealism: "The world is for a subject." This idealism so presented, immediately commits it to an ethical attitude, unlike the purely epistemological concerns of Descartes and Berkeley. To Schopenhauer, the Will is a blind force that controls not only the actions of individual, intelligent agents, but ultimately all observable phenomena—an evil to be terminated via mankind's duties: asceticism and chastity.[168] He is credited with one of the most famous opening lines of philosophy: "The world is my representation." Friedrich Nietzsche was greatly influenced by this idea of Will, although he eventually rejected it.

Art and aesthetics[edit]

For Schopenhauer, human desiring, "willing", and craving cause suffering or pain. A temporary way to escape this pain is through aesthetic contemplation (a method comparable to Zapffe's "Sublimation"). Aesthetic contemplation allows one to escape this pain—albeit temporarily—because it stops one perceiving the world as mere presentation. Instead, one no longer perceives the world as an object of perception (therefore as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds; time, space and causality) from which one is separated; rather one becomes one with that perception: "one can thus no longer separate the perceiver from the perception" (The World as Will and Representation, section 34). From this immersion with the world one no longer views oneself as an individual who suffers in the world due to one's individual will but, rather, becomes a "subject of cognition" to a perception that is "Pure, will-less, timeless" (section 34) where the essence, "ideas", of the world are shown. Art is the practical consequence of this brief aesthetic contemplation as it attempts to depict one's immersion with the world, thus tries to depict the essence/pure ideas of the world. Music, for Schopenhauer, was the purest form of art because it was the one that depicted the will itself without it appearing as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds, therefore as an individual object. According to Daniel Albright, "Schopenhauer thought that music was the only art that did not merely copy ideas, but actually embodied the will itself".[169]

He deemed music a timeless, universal language comprehended everywhere, that can imbue global enthusiasm, if in possession of a significant melody.[170]

Mathematics[edit]

Schopenhauer's realist views on mathematics are evident in his criticism of the contemporaneous attempts to prove the parallel postulate in Euclidean geometry. Writing shortly before the discovery of hyperbolic geometry demonstrated the logical independence of the axiom—and long before the general theory of relativity revealed that it does not necessarily express a property of physical space—Schopenhauer criticized mathematicians for trying to use indirect concepts to prove what he held was directly evident from intuitive perception.

The Euclidean method of demonstration has brought forth from its own womb its most striking parody and caricature in the famous controversy over the theory of parallels, and in the attempts, repeated every year, to prove the eleventh axiom (also known as the fifth postulate). The axiom asserts, and that indeed through the indirect criterion of a third intersecting line, that two lines inclined to each other (for this is the precise meaning of "less than two right angles"), if produced far enough, must meet. Now this truth is supposed to be too complicated to pass as self-evident, and therefore needs a proof; but no such proof can be produced, just because there is nothing more immediate.[171]

Throughout his writings,[172] Schopenhauer criticized the logical derivation of philosophies and mathematics from mere concepts, instead of from intuitive perceptions.

In fact, it seems to me that the logical method is in this way reduced to an absurdity. But it is precisely through the controversies over this, together with the futile attempts to demonstrate the directly certain as merely indirectly certain, that the independence and clearness of intuitive evidence appear in contrast with the uselessness and difficulty of logical proof, a contrast as instructive as it is amusing. The direct certainty will not be admitted here, just because it is no merely logical certainty following from the concept, and thus resting solely on the relation of predicate to subject, according to the principle of contradiction. But that eleventh axiom regarding parallel lines is a synthetic proposition a priori, and as such has the guarantee of pure, not empirical, perception; this perception is just as immediate and certain as is the principle of contradiction itself, from which all proofs originally derive their certainty. At bottom this holds good of every geometrical theorem ...

Although Schopenhauer could see no justification for trying to prove Euclid's parallel postulate, he did see a reason for examining another of Euclid's axioms.[173]

It surprises me that the eighth axiom,[174] "Figures that coincide with one another are equal to one another", is not rather attacked. For "coinciding with one another" is either a mere tautology, or something quite empirical, belonging not to pure intuition or perception, but to external sensuous experience. Thus it presupposes mobility of the figures, but matter alone is movable in space. Consequently, this reference to coincidence with one another forsakes pure space, the sole element of geometry, in order to pass over to the material and empirical.[171]

This follows Kant's reasoning.[175]

Ethics[edit]

The task of ethics is not to prescribe moral actions that ought to be done, but to investigate moral actions. Philosophy is always theoretical: its task to explain what is given.[176]

According to Kant's teaching of transcendental idealism, space and time are forms of our sensibility due to which phenomena appear in multiplicity. Reality in itself is free from all multiplicity, not in the sense that an object is one, but that it is outside the possibility of multiplicity. From this follows that two individuals, though they appear as distinct, are in-themselves not distinct.[177]

The appearances are entirely subordinated to the principle of sufficient reason. The egoistic individual who focuses his aims completely on his own interests has therefore to deal with empirical laws as well as he can.

What is relevant for ethics are individuals who can act against their own self-interest. If we take for example a man who suffers when he sees his fellow men living in poverty, and consequently uses a significant part of his income to support their needs instead his own pleasures, then the simplest way to describe this is that he makes less distinction between himself and others than is usually made.[178]

Regarding how the things appear to us, the egoist is right to assert the gap between two individuals, but the altruist experiences the sufferings of others as his own. In the same way a compassionate man cannot hurt animals, though they appear as distinct from himself.

What motivates the altruist is compassion. The suffering of others is for him not a cold matter to which he is indifferent, but he feels connected to all beings. Compassion is thus the basis of morality.[179]

Eternal justice[edit]

Schopenhauer calls the principle through which multiplicity appears the principium individuationis. When we behold nature we see that it is a cruel battle for existence. Individual manifestations of the will can maintain themselves only at the expense of others—the will, as the only thing that exists, has no other option but to devour itself to experience pleasure. This is a fundamental characteristic of the will, and cannot be circumvented.[180]

Unlike temporal, or human justice, which requires time to repay an evil deed and, "has its seat in the state, as requiting and punishing."[181] Eternal justice, "rules not the state but the world, is not dependent upon human institutions, is not subject to chance and deception, is not uncertain, wavering, and erring, but infallible, fixed, and sure." [182] Eternal justice is not retributive because retribution requires time. There are no delays or reprieves. Instead, punishment is tied the offence, "to the point where the two become one."... "Tormenter and tormented are one. The [Tormenter] errs in that he believes he is not a partaker in the suffering; the [tormented], in that he believes he is not a partaker in the guilt."[183]

Suffering is the moral retribution of our attachment to pleasure. Schopenhauer deemed that this truth was expressed by Christian dogma of original sin and in Eastern religions with the dogma of rebirth.

Quietism[edit]

He who sees through the principium individuationis and comprehends suffering in general as his own, will see suffering everywhere, and instead of using all his force to fight for the happiness of his individual manifestation, he will abhor life itself, of which he knows how inseparably it is connected with suffering. A happy individual life midst a world of suffering is for him like a beggar who dreams one night that he is a king.[184]

Those who have experienced this intuitive knowledge can no longer affirm life, but will exhibit asceticism and quietism, meaning that they are no longer sensitive to motives, are not concerned about their individual welfare, and accept the evil others inflict on them without resisting. They welcome poverty, do not seek nor flee death.[184]

Human life is a ceaseless struggle for satisfaction, and instead of renewing this contract, the ascetic breaks it. It matters little whether these ascetics adhered to the dogmata of Christianity or Dharmic religions, since their way of living is the result of intuitive knowledge.

The Christian mystic and the teacher of the Vedanta philosophy agree in this respect also, they both regard all outward works and religious exercises as superfluous for him who has attained to perfection. So much agreement in the case of such different ages and nations is a practical proof that what is expressed here is not, as optimistic dullness likes to assert, an eccentricity and perversity of the mind, but an essential side of human nature, which only appears so rarely because of its excellence.[184]

Schopenhauer referred to asceticism as the denial of the will to live.

Psychology[edit]

Philosophers have not traditionally been impressed by the tribulations of sex, but Schopenhauer addressed it and related concepts forthrightly:

... one ought rather to be surprised that a thing [sex] which plays throughout so important a part in human life has hitherto practically been disregarded by philosophers altogether, and lies before us as raw and untreated material.[185]

He named a force within man that he felt took invariable precedence over reason: the Will to Live or Will to Life (Wille zum Leben), defined as an inherent drive within human beings, and indeed all creatures, to stay alive; a force that inveigles[168] us into reproducing.

Schopenhauer refused to conceive of love as either trifling or accidental, but rather understood it as an immensely powerful force that lay unseen within man's psyche, guaranteeing the quality of the human race:

The ultimate aim of all love affairs ... is more important than all other aims in man's life; and therefore it is quite worthy of the profound seriousness with which everyone pursues it. What is decided by it is nothing less than the composition of the next generation ...[186]

It has often been argued that Schopenhauer's thoughts on sexuality foreshadowed the theory of evolution, a claim that seems to have been met with satisfaction by Darwin as he included a quote of the German philosopher in his Descent of Man after having read such a claim.[187] This has also been noted about Freud's concepts of the libido and the unconscious mind, and evolutionary psychology in general.[188]

Political and social thought[edit]

Politics[edit]

Schopenhauer's politics were, for the most part, an echo of his system of ethics (the latter being expressed in Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik, available in English as two separate books, On the Basis of Morality and On the Freedom of the Will). Ethics also occupies about one quarter of his central work, The World as Will and Representation.

In occasional political comments in his Parerga and Paralipomena and Manuscript Remains, Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. What was essential, he thought, was that the state should "leave each man free to work out his own salvation," and so long as government was thus limited, he would "prefer to be ruled by a lion than one of [his] fellow rats"—i.e., by a monarch, rather than a democrat. Schopenhauer shared the view of Thomas Hobbes on the necessity of the state, and of state action, to check the destructive tendencies innate to our species. He also defended the independence of the legislative, judicial and executive branches of power, and a monarch as an impartial element able to practise justice (in a practical and everyday sense, not a cosmological one).[189] He declared monarchy as "that which is natural to man" for "intelligence has always under a monarchical government a much better chance against its irreconcilable and ever-present foe, stupidity" and disparaged republicanism as "unnatural as it is unfavourable to the higher intellectual life and the arts and sciences."[190]

Schopenhauer, by his own admission, did not give much thought to politics, and several times he writes proudly of how little attention he had paid "to political affairs of [his] day". In a life that spanned several revolutions in French and German government, and a few continent-shaking wars, he did indeed maintain his aloof position of "minding not the times but the eternities". He wrote many disparaging remarks about Germany and the Germans. A typical example is, "For a German it is even good to have somewhat lengthy words in his mouth, for he thinks slowly, and they give him time to reflect."[191]

Schopenhauer attributed civilizational primacy to the northern "white races" due to their sensitivity and creativity (except for the ancient Egyptians and Hindus, whom he saw as equal):

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in colour than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmans, the Incas, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate. This they had to do in order to make up for the parsimony of nature and out of it all came their high civilization.[192]

Despite this, he was adamantly against differing treatment of races, was fervently anti-slavery, and supported the abolitionist movement in the United States. He describes the treatment of "[our] innocent black brothers whom force and injustice have delivered into [the slave-master's] devilish clutches" as "belonging to the blackest pages of mankind's criminal record".[193]

Schopenhauer additionally maintained a marked metaphysical and political anti-Judaism. Schopenhauer argued that Christianity constituted a revolt against what he styled the materialistic basis of Judaism, exhibiting an Indian-influenced ethics reflecting the Aryan-Vedic theme of spiritual self-conquest. He saw this as opposed to what he held was the ignorant drive toward earthly utopianism and superficiality of a worldly "Jewish" spirit:

While all other religions endeavor to explain to the people by symbols the metaphysical significance of life, the religion of the Jews is entirely immanent and furnishes nothing but a mere war-cry in the struggle with other nations.[194]

Punishment[edit]

The State, Schopenhauer claimed, punishes criminals to prevent future crimes. It does so by placing "beside every possible motive for committing a wrong a more powerful motive for leaving it undone, in the inescapable punishment. Accordingly, the criminal code is as complete a register as possible of counter-motives to all criminal actions that can possibly be imagined ..."[195] He claimed this doctrine was not original to him. Previously, it appeared in the writings of Plato,[196] Seneca, Hobbes, Pufendorf, and Anselm Feuerbach.

Views on women[edit]

In Schopenhauer's 1851 essay On Women, he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico-Christian stupidity" of reflexive unexamined reverence ("abgeschmackten Weiberveneration")[197] for the female. Schopenhauer wrote that "Women are directly fitted for acting as the nurses and teachers of our early childhood by the fact that they are themselves childish, frivolous and short-sighted." He opined that women are deficient in artistic faculties and sense of justice, and expressed opposition to monogamy. Indeed, Rodgers and Thompson in Philosophers Behaving Badly call Schopenhauer "a misogynist without rival in ... Western philosophy". He claimed that "woman is by nature meant to obey". The essay does give some compliments, however: that "women are decidedly more sober in their judgment than [men] are", and are more sympathetic to the suffering of others.

Schopenhauer's writings have influenced many, from Friedrich Nietzsche to nineteenth-century feminists.[198] Schopenhauer's biological analysis of the difference between the sexes, and their separate roles in the struggle for survival and reproduction, anticipates some of the claims that were later ventured by sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists.[199]

When the elderly Schopenhauer sat for a sculpture portrait by the Prussian sculptor Elisabet Ney in 1859, he was much impressed by the young woman's wit and independence, as well as by her skill as a visual artist.[200] After his time with Ney, he told Richard Wagner's friend Malwida von Meysenbug, "I have not yet spoken my last word about women. I believe that if a woman succeeds in withdrawing from the mass, or rather raising herself above the mass, she grows ceaselessly and more than a man."[201]

Heredity and eugenics[edit]

Schopenhauer viewed personality and intellect as being inherited. He quotes Horace's saying, "From the brave and good are the brave descended" (Odes, iv, 4, 29) and Shakespeare's line from Cymbeline, "Cowards father cowards, and base things sire base" (IV, 2) to reinforce his hereditarian argument.[202] Mechanistically, Schopenhauer believed that a person inherits his level of intellect through his mother, and personal character through one's father.[203] This belief in heritability of traits informed Schopenhauer's view of love – placing it at the highest level of importance. For Schopenhauer the "final aim of all love intrigues, be they comic or tragic, is really of more importance than all other ends in human life. What it all turns upon is nothing less than the composition of the next generation. ... It is not the weal or woe of any one individual, but that of the human race to come, which is here at stake." This view of the importance for the species of whom we choose to love was reflected in his views on eugenics or good breeding. Here Schopenhauer wrote:

With our knowledge of the complete unalterability both of character and of mental faculties, we are led to the view that a real and thorough improvement of the human race might be reached not so much from outside as from within, not so much by theory and instruction as rather by the path of generation. Plato had something of the kind in mind when, in the fifth book of his Republic, he explained his plan for increasing and improving his warrior caste. If we could castrate all scoundrels and stick all stupid geese in a convent, and give men of noble character a whole harem, and procure men, and indeed thorough men, for all girls of intellect and understanding, then a generation would soon arise which would produce a better age than that of Pericles.[204]

In another context, Schopenhauer reiterated his eugenic thesis: "If you want Utopian plans, I would say: the only solution to the problem is the despotism of the wise and noble members of a genuine aristocracy, a genuine nobility, achieved by mating the most magnanimous men with the cleverest and most gifted women. This proposal constitutes my Utopia and my Platonic Republic."[205] Analysts (e.g., Keith Ansell-Pearson) have suggested that Schopenhauer's anti-egalitarianist sentiment and his support for eugenics influenced the neo-aristocratic philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, who initially considered Schopenhauer his mentor.[206]

Animal welfare[edit]

As a consequence of his monistic philosophy, Schopenhauer was very concerned about the welfare of animals.[207][208] For him, all individual animals, including humans, are essentially the same, being phenomenal manifestations of the one underlying Will. The word "will" designated, for him, force, power, impulse, energy, and desire; it is the closest word we have that can signify both the real essence of all external things and also our own direct, inner experience. Since every living thing possesses will, then humans and animals are fundamentally the same and can recognize themselves in each other.[209] For this reason, he claimed that a good person would have sympathy for animals, who are our fellow sufferers.

Compassion for animals is intimately associated with goodness of character, and it may be confidently asserted that he who is cruel to living creatures cannot be a good man.

— On the basis of morality, § 19

Nothing leads more definitely to a recognition of the identity of the essential nature in animal and human phenomena than a study of zoology and anatomy.

— On the basis of morality, chapter 8[210]

The assumption that animals are without rights and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality.

— On the basis of morality, chapter 8[211]

In 1841, he praised the establishment, in London, of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and also the Animals' Friends Society in Philadelphia. Schopenhauer even went so far as to protest against the use of the pronoun "it" in reference to animals because it led to the treatment of them as though they were inanimate things.[212] To reinforce his points, Schopenhauer referred to anecdotal reports of the look in the eyes of a monkey who had been shot[213] and also the grief of a baby elephant whose mother had been killed by a hunter.[214]

He was very attached to his succession of pet poodles. Schopenhauer criticized Spinoza's[215] belief that animals are a mere means for the satisfaction of humans.[216][217]

Views on pederasty[edit]

In the third, expanded edition of The World as Will and Representation (1859), Schopenhauer added an appendix to his chapter on the Metaphysics of Sexual Love. He wrote that pederasty did have the benefit of preventing ill-begotten children. Concerning this, he stated that "the vice we are considering appears to work directly against the aims and ends of nature, and that in a matter that is all important and of the greatest concern to her it must in fact serve these very aims, although only indirectly, as a means for preventing greater evils".[218] Schopenhauer ends the appendix with the statement that "by expounding these paradoxical ideas, I wanted to grant to the professors of philosophy a small favour. I have done so by giving them the opportunity of slandering me by saying that I defend and commend pederasty."[219]

Intellectual interests and affinities[edit]

Indology[edit]

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation of the ancient Hindu texts, the Upanishads, which French writer Anquetil du Perron had translated from the Persian translation of Prince Dara Shukoh entitled Sirre-Akbar ("The Great Secret"). He was so impressed by their philosophy that he called them "the production of the highest human wisdom", and believed they contained superhuman concepts. The Upanishads was a great source of inspiration to Schopenhauer. Writing about them, he said:

It is the most satisfying and elevating reading (with the exception of the original text) which is possible in the world; it has been the solace of my life and will be the solace of my death.[220]

The book Oupnekhat (Upanishad) always lay open on his table, and he invariably studied it before sleeping at night. He called the opening up of Sanskrit literature "the greatest gift of our century" and predicted that the philosophy and knowledge of the Upanishads would become the cherished faith of the West.[221]

Schopenhauer was first introduced to the 1802 Latin Upanishad translation through Friedrich Majer. They met during the winter of 1813–1814 in Weimar at the home of Schopenhauer's mother according to the biographer Safranski. Majer was a follower of Herder, and an early Indologist. Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of the Indic texts, however, until the summer of 1814. Safranski maintains that between 1815 and 1817, Schopenhauer had another important cross-pollination with Indian thought in Dresden. This was through his neighbor of two years, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause. Krause was then a minor and rather unorthodox philosopher who attempted to mix his own ideas with that of ancient Indian wisdom. Krause had also mastered Sanskrit, unlike Schopenhauer, and the two developed a professional relationship. It was from Krause that Schopenhauer learned meditation and received the closest thing to expert advice concerning Indian thought.[222]

Most noticeable, in the case of Schopenhauer's work, was the significance of the Chandogya Upanishad, whose Mahāvākya, Tat Tvam Asi, is mentioned throughout The World as Will and Representation.[223]

Buddhism[edit]

Schopenhauer noted a correspondence between his doctrines and the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism.[224] Similarities centered on the principles that life involves suffering, that suffering is caused by desire (taṇhā), and that the extinction of desire leads to liberation. Thus three of the four "truths of the Buddha" correspond to Schopenhauer's doctrine of the will.[225] In Buddhism, however, while greed and lust are always unskillful, desire is ethically variable – it can be skillful, unskillful, or neutral.[226]

For Schopenhauer, will had ontological primacy over the intellect. In other words, desire is prior to thought. Schopenhauer felt this was similar to notions of puruṣārtha or goals of life in Vedānta Hinduism.

In Schopenhauer's philosophy, denial of the will is attained by either:

- personal experience of an extremely great suffering that leads to loss of the will to live; or

- knowledge of the essential nature of life in the world through observation of the suffering of other people.

However, Buddhist nirvāṇa is not equivalent to the condition that Schopenhauer described as denial of the will. Nirvāṇa is not the extinguishing of the person as some Western scholars have thought, but only the "extinguishing" (the literal meaning of nirvana) of the flames of greed, hatred, and delusion that assail a person's character.[227] Occult historian Joscelyn Godwin (born 1945) stated, "It was Buddhism that inspired the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, and, through him, attracted Richard Wagner."[228] This Orientalism reflected the struggle of the German Romantics, in the words of Leon Poliakov, to "free themselves from Judeo-Christian fetters".[229] In contradistinction to Godwin's claim that Buddhism inspired Schopenhauer, the philosopher himself made the following statement in his discussion of religions:[230]

If I wished to take the results of my philosophy as the standard of truth, I should have to concede to Buddhism pre-eminence over the others. In any case, it must be a pleasure to me to see my doctrine in such close agreement with a religion that the majority of men on earth hold as their own, for this numbers far more followers than any other. And this agreement must be yet the more pleasing to me, inasmuch as in my philosophizing I have certainly not been under its influence [emphasis added]. For up till 1818, when my work appeared, there was to be found in Europe only a very few accounts of Buddhism.[231]

Buddhist philosopher Nishitani Keiji, however, sought to distance Buddhism from Schopenhauer.[232] While Schopenhauer's philosophy may sound rather mystical in such a summary, his methodology was resolutely empirical, rather than speculative or transcendental:

Philosophy ... is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions.[233]

Also note:

This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.[234]

The argument that Buddhism affected Schopenhauer's philosophy more than any other Dharmic faith loses more credence when viewed in light of the fact that Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of Buddhism until after the publication of The World as Will and Representation in 1818.[235] Scholars have started to revise earlier views about Schopenhauer's discovery of Buddhism. Proof of early interest and influence, however, appears in Schopenhauer's 1815/16 notes (transcribed and translated by Urs App) about Buddhism. They are included in a recent case study that traces Schopenhauer's interest in Buddhism and documents its influence.[236] Other scholarly work questions how similar Schopenhauer's philosophy actually is to Buddhism.[237]

Magic and occultism[edit]

Some traditions in Western esotericism and parapsychology interested Schopenhauer and influenced his philosophical theories. He praised animal magnetism as evidence for the reality of magic in his On the Will in Nature, and went so far as to accept the division of magic into left-hand and right-hand magic, although he doubted the existence of demons.[238]

Schopenhauer grounded magic in the Will and claimed all forms of magical transformation depended on the human Will, not on ritual. This theory notably parallels Aleister Crowley's system of magick and its emphasis on human will.[238] Given the importance of the Will to Schopenhauer's overarching system, this amounts to "suggesting his whole philosophical system had magical powers."[239] Schopenhauer rejected the theory of disenchantment and claimed philosophy should synthesize itself with magic, which he believed amount to "practical metaphysics."[240]

Neoplatonism, including the traditions of Plotinus and to a lesser extent Marsilio Ficino, has also been cited as an influence on Schopenhauer.[241]

Interests[edit]

Schopenhauer had a wide range of interests, from science and opera to occultism and literature.

In his student years Schopenhauer went more often to lectures in the sciences than philosophy. He kept a strong interest as his personal library contained near to 200 books of scientific literature at his death, and his works refer to scientific titles not found in the library.[35]:170

Many evenings were spent in the theatre, opera and ballet; the operas of Mozart, Rossini and Bellini were especially esteemed.[242] Schopenhauer considered music the highest art, and played the flute during his whole life.[35]:30

As a polyglot, the philosopher knew German, Italian, Spanish, French, English, Latin and ancient Greek, and he was an avid reader of poetry and literature. He particularly revered Goethe, Petrarch, Calderón and Shakespeare.

If Goethe had not been sent into the world simultaneously with Kant in order to counterbalance him, so to speak, in the spirit of the age, the latter would have been haunted like a nightmare many an aspiring mind and would have oppressed it with great affliction. But now the two have an infinitely wholesome effect from opposite directions and will probably raise the German spirit to a height surpassing even that of antiquity.[35]:240

In philosophy, his most important influences were, according to himself, Kant, Plato and the Upanishads. Concerning the Upanishads and Vedas, he writes in The World as Will and Representation:

If the reader has also received the benefit of the Vedas, the access to which by means of the Upanishads is in my eyes the greatest privilege which this still young century (1818) may claim before all previous centuries, if then the reader, I say, has received his initiation in primeval Indian wisdom, and received it with an open heart, he will be prepared in the very best way for hearing what I have to tell him. It will not sound to him strange, as to many others, much less disagreeable; for I might, if it did not sound conceited, contend that every one of the detached statements which constitute the Upanishads, may be deduced as a necessary result from the fundamental thoughts which I have to enunciate, though those deductions themselves are by no means to be found there.[243]

Thoughts on other philosophers[edit]

Giordano Bruno and Spinoza[edit]

Schopenhauer saw Bruno and Spinoza as unique philosophers who were not bound to their age or nation. "Both were fulfilled by the thought, that as manifold the appearances of the world may be, it is still one being, that appears in all of them. ... Consequently, there is no place for God as creator of the world in their philosophy, but God is the world itself."[244][245]

Schopenhauer expressed his regret that Spinoza stuck for the presentation of his philosophy with the concepts of scholasticism and Cartesian philosophy, and tried to use geometrical proofs that do not hold because of the vagueness and wideness of the definitions. It is the common preference of philosophers of abstraction over perception. Bruno on the other hand, who knew much about nature and ancient literature, presents his ideas with Italian vividness, and is amongst philosophers the only one who comes near Plato's poetic and dramatic power of exposition.[244][245]

Schopenhauer noted that their philosophies do not provide any ethics, and it is therefore very remarkable that Spinoza called his main work Ethics. In fact, it could be considered complete from the standpoint of life-affirmation, if one completely ignores morality and self-denial.[246] It is yet even more remarkable that Schopenhauer mentions Spinoza as an example of the denial of the will, if one uses the French biography by Jean Maximilien Lucas [247] as the key to Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione.[248]

Immanuel Kant[edit]

The importance of Kant for Schopenhauer, in philosophy as well as on a personal level, can hardly be overstated. The philosophy of Kant was the foundation of his own. Schopenhauer maintained that Kant stands in the same relation to philosophers such as Berkeley and Plato, as Copernicus to Hicetas, Philolaus, and Aristarchus: Kant succeeded in demonstrating what previous philosophers merely asserted.

In his study room one bust was of Buddha, the other was of Kant.[249] The bond which Schopenhauer felt with the philosopher of Königsberg may be esteemed in a poem he dedicated to Kant:

With my eyes I followed thee into the blue sky,

And there thy flight dissolved from view.

Alone I stayed in the crowd below,

Thy word and thy book my only solace. —

Schopenhauer dedicated one fifth of his main work, The World as Will and Representation, to a criticism of the Kantian philosophy.

Post-Kantian school[edit]

The leading figures of post-Kantian philosophy, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, were not respected by Schopenhauer. He argued that they were no philosophers at all, who merely sought to impress the public.

All this explains the painful impression with which we are seized when, after studying genuine thinkers, we come to the writings of Fichte and Schelling, or even to the presumptuously scribbled nonsense of Hegel, produced as it was with a boundless, though justified, confidence in German stupidity. With those genuine thinkers one always found an honest investigation of truth and just as honest an attempt to communicate their ideas to others. Therefore whoever reads Kant, Locke, Hume, Malebranche, Spinoza, and Descartes feels elevated and agreeably impressed. This is produced through communion with a noble mind which has and awakens ideas and which thinks and sets one thinking. The reverse of all this takes place when we read the above-mentioned three German sophists. An unbiased reader, opening one of their books and then asking himself whether this is the tone of a thinker wanting to instruct or that of a charlatan wanting to impress, cannot be five minutes in any doubt; here everything breathes so much of dishonesty.

— Appendix to "Sketch of a History of the Doctrine of the Ideal and the Real"

Schelling was deemed the most talented of the three, and Schopenhauer wrote that he would recommend his "elucidatory paraphrase of the highly important doctrine of Kant" concerning the intelligible character, if he had been honest enough to admit he was showing off with the thoughts of Kant, instead of hiding this relation in a cunning manner.[250]

Schopenhauer's favourite subject of attacks was Hegel, whom he considered unworthy even of Fichte and Schelling. Whereas Fichte was merely a windbag, Hegel was a "stupid and clumsy charlatan". Karl Popper agreed with this distinction.[251]

Influence[edit]

Schopenhauer had a large posthumous effect and remained the most influential German philosopher until the First World War.[252] His philosophy was a starting point for a new generation of philosophers, which consisted of Julius Bahnsen, Paul Deussen, Lazar von Hellenbach, Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, Ernst Otto Lindner, Philipp Mainländer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Olga Plümacher and Agnes Talbert. His legacy shaped the intellectual debate, and forced movements that were utterly opposed to him, neo-Kantianism and positivism, to address issues they would otherwise have completely ignored, and in doing so he changed them markedly.[252] The French writer Maupassant commented that "to-day even those who execrate him seem to carry in their own souls particles of his thought."[253] Other philosophers of the 19th century who cited his influence include Hans Vaihinger, Volkelt, Solovyov and Weininger.

Schopenhauer was well read amongst physicists, most notably Einstein, Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli,[254] and Majorana.[12] Einstein described Schopenhauer's thoughts as a "continual consolation" and called him a genius.[255] In his Berlin study three figures hung on the wall: Faraday, Maxwell, Schopenhauer.[256]:87 Konrad Wachsmann recalled: "He often sat with one of the well-worn Schopenhauer volumes, and as he sat there, he seemed so pleased, as if he were engaged with a serene and cheerful work."[256]:92

When Erwin Schrödinger discovered Schopenhauer ("the greatest savant of the West") he considered switching his study of physics to philosophy.[257] He maintained the idealistic views during the rest of his life.[256]:132 Wolfgang Pauli accepted the main tenet of Schopenhauer's metaphysics, that the thing-in-itself is will.[258]

But most of all Schopenhauer is famous for his influence on artists. Richard Wagner became one of the earliest and most famous adherents of the Schopenhauerian philosophy.[259] The admiration was not mutual, and Schopenhauer proclaimed: "I remain faithful to Rossini and Mozart!"[260] So he has been nicknamed "the artist's philosopher".[3] See also Influence of Schopenhauer on Tristan und Isolde.

Under the influence of Schopenhauer Leo Tolstoy became convinced that the truth of all religions lies in self-renunciation. When he read his philosophy he exclaimed "at present I am convinced that Schopenhauer is the greatest genius among men. ... It is the whole world in an incomparably beautiful and clear reflection."[261] He said that what he has written in War and Peace is also said by Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation.[262]